Framing Fatherhood: from Redemption to Dysfunction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1997 Sundance Film Festival Awards Jurors

1997 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL The 1997 Sundance Film Festival continued to attract crowds, international attention and an appreciative group of alumni fi lmmakers. Many of the Premiere fi lmmakers were returning directors (Errol Morris, Tom DiCillo, Victor Nunez, Gregg Araki, Kevin Smith), whose earlier, sometimes unknown, work had received a warm reception at Sundance. The Piper-Heidsieck tribute to independent vision went to actor/director Tim Robbins, and a major retrospective of the works of German New-Wave giant Rainer Werner Fassbinder was staged, with many of his original actors fl own in for forums. It was a fi tting tribute to both Fassbinder and the Festival and the ways that American independent cinema was indeed becoming international. AWARDS GRAND JURY PRIZE JURY PRIZE IN LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA Documentary—GIRLS LIKE US, directed by Jane C. Wagner and LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY (O SERTÃO DAS MEMÓRIAS), directed by José Araújo Tina DiFeliciantonio SPECIAL JURY AWARD IN LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA Dramatic—SUNDAY, directed by Jonathan Nossiter DEEP CRIMSON, directed by Arturo Ripstein AUDIENCE AWARD JURY PRIZE IN SHORT FILMMAKING Documentary—Paul Monette: THE BRINK OF SUMMER’S END, directed by MAN ABOUT TOWN, directed by Kris Isacsson Monte Bramer Dramatic—HURRICANE, directed by Morgan J. Freeman; and LOVE JONES, HONORABLE MENTIONS IN SHORT FILMMAKING directed by Theodore Witcher (shared) BIRDHOUSE, directed by Richard C. Zimmerman; and SYPHON-GUN, directed by KC Amos FILMMAKERS TROPHY Documentary—LICENSED TO KILL, directed by Arthur Dong Dramatic—IN THE COMPANY OF MEN, directed by Neil LaBute DIRECTING AWARD Documentary—ARTHUR DONG, director of Licensed To Kill Dramatic—MORGAN J. -

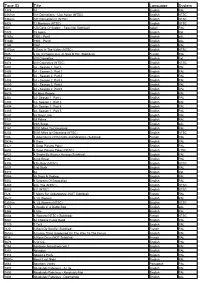

Tape ID Title Language System

Tape ID Title Language System 1375 10 English PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English NTSC 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian PAL 1078 18 Again English Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English pAL 1244 1941 English PAL 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English NTSC f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French PAL 1304 200 Cigarettes English Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English NTSC 2401 24 - Season 1, Vol 1 English PAL 2406 24 - Season 2, Part 1 English PAL 2407 24 - Season 2, Part 2 English PAL 2408 24 - Season 2, Part 3 English PAL 2409 24 - Season 2, Part 4 English PAL 2410 24 - Season 2, Part 5 English PAL 5675 24 Hour People English PAL 2402 24- Season 1, Part 2 English PAL 2403 24- Season 1, Part 3 English PAL 2404 24- Season 1, Part 4 English PAL 2405 24- Season 1, Part 5 English PAL 3287 28 Days Later English PAL 5731 29 Palms English PAL 5501 29th Street English pAL 3141 3000 Miles To Graceland English PAL 6234 3000 Miles to Graceland (NTSC) English NTSC f103 4 Adventures Of Reinette and Mirabelle (Subtitled) French PAL 0514s 4 Days English PAL 3421 4 Dogs Playing Poker English PAL 6607 4 Dogs Playing Poker (NTSC) English nTSC g033 4 Shorts By Werner Herzog (Subtitled) English PAL 0160 42nd Street English PAL 6306 4Th Floor (NTSC) English NTSC 3437 51st State English PAL 5310 54 English Pal 0058 55 Days At Peking English PAL 3052 6 Degrees Of Separation English PAL 6389 60s, The (NTSC) English NTSC 6555 61* (NTSC) English NTSC f126 7 Morts Sur Ordonnance (NOT Subtitled) French PAL 5623 8 1/2 Women English PAL 0253sn 8 1/2 Women (NTSC) English NTSC 1175 8 Heads In A Duffel Bag English pAL 5344 8 Mile English PAL 6088 8 Women (NTSC) (Subtitled) French NTSC 5041 84 Charing Cross Road English PAL 1129 9 To 5 English PAL f220 A Bout De Souffle (Subtitled) French PAL 0652s A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum English PAL f018 A Nous Deux (NOT Subtitled) French PAL 3676 A.W.O.L. -

Movieguide.Pdf

Movies Without Nudity A guide to nudity in 8,345 movies From www.movieswithoutnudity.com Red - Contains Nudity Movies I Own 300: Rise of an Empire (2014) A. I. - Artificial Intelligence (2001) A La Mala (aka Falling for Mala) (2014) A-X-L (2018) A.C.O.D. (2013) [Male rear nudity] Abandon (2002) The Abandoned (2007) Abe Lincoln in Illinois (1940) Abel's Field (2012) The Abolitionists (2016) Abominable (2019) Abominable (2020) About a Boy (2002) About Adam (2001) About Last Night (1986) About Last Night (2014) About Schmidt (2002) About Time (2013) Above and Beyond (2014) Above Suspicion (1995) Above the Rim (1994) Abraham (1994) [Full nudity of boys playing in water] The Absent-Minded Professor (1961) Absolute Power (1997) Absolutely Fabulous: The Movie (2016) An Acceptable Loss (2019) Accepted (2006) The Accountant (2016) Ace in the Hole (1951) Ace Ventura: When Nature Calls (1995) [male rear nudity] Achilles' Love (2000) Across the Moon (1995) Across the Universe (2007) Action Jackson (1988) Action Point (2018) Acts of Violence (2018) Ad Astra (2019) Adam (2009) Adam at 6 A.M. (1970) Adam Had Four Sons (1941) Adam Sandler's Eight Crazy Nights (2002) Adam's Apples (2007) Adam's Rib (1949) Adaptation (2002) The Addams Family (2019) Addams Family Values (1993) Addicted (2014) Addicted to Love (1997) [Depends on who you ask, but dark shadows obscure any nudity.] The Adjuster (1991) The Adjustment Bureau (2011) The Admiral: Roaring Currents (aka Myeong-ryang) (2014) Admission (2013) Adrenaline Rush (2002) Adrift (2018) Adult Beginners (2015) Adult Life Skills (2019) [Drawings of penises] Adventures in Dinosaur City (1992) Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1989) Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension (1984) The Adventures of Elmo In Grouchland (1999) The Adventures of Huck Finn (1993) Adventures of Icabod and Mr. -

Id Title Year Format Cert 20802 Tenet 2020 DVD 12 20796 Bit 2019 DVD

Id Title Year Format Cert 20802 Tenet 2020 DVD 12 20796 Bit 2019 DVD 15 20795 Those Who Wish Me Dead 2021 DVD 15 20794 The Father 2020 DVD 12 20793 A Quiet Place Part 2 2020 DVD 15 20792 Cruella 2021 DVD 12 20791 Luca 2021 DVD U 20790 Five Feet Apart 2019 DVD 12 20789 Sound of Metal 2019 BR 15 20788 Promising Young Woman 2020 DVD 15 20787 The Mountain Between Us 2017 DVD 12 20786 The Bleeder 2016 DVD 15 20785 The United States Vs Billie Holiday 2021 DVD 15 20784 Nomadland 2020 DVD 12 20783 Minari 2020 DVD 12 20782 Judas and the Black Messiah 2021 DVD 15 20781 Ammonite 2020 DVD 15 20780 Godzilla Vs Kong 2021 DVD 12 20779 Imperium 2016 DVD 15 20778 To Olivia 2021 DVD 12 20777 Zack Snyder's Justice League 2021 DVD 15 20776 Raya and the Last Dragon 2021 DVD PG 20775 Barb and Star Go to Vista Del Mar 2021 DVD 15 20774 Chaos Walking 2021 DVD 12 20773 Treacle Jr 2010 DVD 15 20772 The Swordsman 2020 DVD 15 20771 The New Mutants 2020 DVD 15 20770 Come Away 2020 DVD PG 20769 Willy's Wonderland 2021 DVD 15 20768 Stray 2020 DVD 18 20767 County Lines 2019 BR 15 20767 County Lines 2019 DVD 15 20766 Wonder Woman 1984 2020 DVD 12 20765 Blackwood 2014 DVD 15 20764 Synchronic 2019 DVD 15 20763 Soul 2020 DVD PG 20762 Pixie 2020 DVD 15 20761 Zeroville 2019 DVD 15 20760 Bill and Ted Face the Music 2020 DVD PG 20759 Possessor 2020 DVD 18 20758 The Wolf of Snow Hollow 2020 DVD 15 20757 Relic 2020 DVD 15 20756 Collective 2019 DVD 15 20755 Saint Maud 2019 DVD 15 20754 Hitman Redemption 2018 DVD 15 20753 The Aftermath 2019 DVD 15 20752 Rolling Thunder Revue 2019 -

Moments #2 2019

MOMENTSA MAGAZINE BY THE SWEDISH EXHIBITION & CONGRESS CENTRE AND GOTHIA TOWERS | 2 | 2019 THE WINNING PROPOSAL FOR +ONE PRALINE PERFECTION A REAL HANDICRAFT DANNY DREAMS BIG NORDIC CRIME CATCHES ON SAY HELLO TO THE HYBRID AGE VÄND FÖR SVENSK VERSION! We meet in a world of experiences EVERY YEAR, WE welcome over 2 million visitors, a figure which has steadily grown in recent years and of which we are enormously proud. It shows that we have succeeded in our goal to create a global meeting place and that physical encounters are becoming ever more important in a digital world. The opportunity to experience something in the moment and to share it with like-minded people is endlessly attractive, whether this involves visits from authors at the Göteborg Book Fair, an innovation day at one of our trade fairs, or a long-awaited show at The Theatre. New ideas are born here with us every day; relation- ships are built and development is pushed forward. We are inspired by all of our visitors and we constantly continue to grow. Right now, we are planning new content, new concepts and our fourth tower, a project entitled +One. It is cer- tain to be an exciting new landmark for Gothenburg. People unite from all over the world under our roof, and our task is to meet your wishes, energize and pique your curiosity, and – hopefully – exceed your expectations. Enjoy a day The same can be said for the magazine you hold in your of spooky fun at hands right now. Liseberg Amusement Welcome! Park for Halloween! CARIN KINDBOM Hotel room & breakfast from PRESIDENT AND CEO THE SWEDISH EXHIBITION SEK 570/adult. -

Clubhouse Network Newsletter Issue

PLEASE Clubhouse Network TAKE ONE Newsletter THEY’RE FREE Hello everyone, this is the seventeenth edition of the Clubhouse Network Newsletter made by volunteers and customers of the Clubhouse Community. Thanks to everyone who made contributions to this issue. We welcome any articles or ideas from Clubhouse customers. Pop-up Clubhouse Opens in Meir Brighter Futures has a new Pop-Up Clubhouse extending the reach of the Clubhouse Network into the southern part of Stoke-on-Trent. We are based at Meir Education Community Centre at Pickford Place with drop-ins every Tuesday and Thursday between 11am and 4pm. We offer a safe space to come to talk to the team for advice and support and it’s a great opportunity to meet others from the community and make new friends, everyone is welcome. Activities include arts and crafts, cooking Support Worker Katie and a Visitor to the Pop-Up Clubhouse classes, knitting/ crocheting, bingo, walking groups, wellbeing workshops, relaxation and anxiety workshops and we are always open to new ideas and activities we can do. You can stay all day or drop in for a bit. We have light snacks, tea and coffee at discounted prices. If you would like any further information about the project or would just like to chat to a member of staff before you visit you can call one of the The Queue for the Delicious Food support workers: The food for the opening was provided by Country Kitchen. Katie: 07824 630858 Sara 07824 638088 Have fun with this Sudoku Puzzle! Liverpool Giant Puppets in Liverpool A trip to Liverpool was undertaken by Lou, Becky and Charlotte to see the Royal de Luxe Giant Puppets for the final time before they are retired. -

A Glimpse of Europe

a glimpse of Europe come to H4.35 Palais des Festivals for the full picture mipcom 2013 media-stands.eu This catalogue showcases the productions of European companies on the MEDIA umbrella stand at MIPCOM 2013, and contains full details of all the companies to be found on the stand at H4.35 on the 4th and 5th floors of the Palais des Festivals. You are welcome to stop by and meet some of the 250 producers, media distributors and content providers gathered under the MEDIA / umbrella. The catalogue contains information on companies with dedicated booths (and a plan of how to find them). Otherwise, the hostesses at the Welcome Desk on the 4 th floor will be happy to set up meetings for you with anyone on the stand. We also have a who’s who console in the welcome area, so you can check what someone looks like and also send an e-mail message to anyone you want to contact. They can arrange to meet you in a room with screening facilities or you can have coffee together in the bar and lounge area. Or just stop by the bar on the 5 th floor for a glass of wine during our Happy Hour from 5-7 p.m. each day. ec.europa.eu The MEDIA Programme aims to strengthen the European audiovisual industry. It is the largest public source of finance for the circulation of European audiovisual work – providing funding for training, development, distribution and promotion. mipcom 07 > 10.10 2013 02 diary catalogue: a glimpse of Europe 08 animation 25 children | youth 28 documentary 44 factual | magazine 47 fiction 63 formats 65 interactive content | cross-media 67 sport | leisure 69 index of productions - a > z 73 index of companies on the stand - a > z 85 stand plan | dedicated booths NotEs – Production synopses are based on information provided by MEDIA umbrella stands participants. -

Clubhouse Network Newsletter Issue

PLEASE Clubhouse Network TAKE ONE Newsletter THEY’RE FREE Hello everyone, this is the twentieth edition of the Clubhouse Network Newsletter made by volunteers and customers of the Clubhouse Community. Thanks to everyone who made contributions to this issue. We welcome any articles or ideas from Clubhouse customers. Sense of Unity by Dundu and Worldbeaters Light Night by Appetite in partnership with Stoke-on-Trent City Council and the Cultural Forum lit up Burslem like never before. The many acts, projections on to buildings and a fascinating soundscape created an enthralling multi-sensory display which was very Ghosts of the Leopard much enjoyed by Clubhouse members. Sense of Unity with the giant puppets Dundu and baby Dundu featured #SOTCulture world inspired rhythms and was wildly popular. Phil S, Phil B and Howard having a great time Our heritage and cultural assets are our inheritance that we can build on as we regenerate this unique city. Have fun with this Sudoku Puzzle! Recovery Assistance Dogs Here Dave talks about his assistance dog Lucky. (The solution is on the Dave with his new assistance dog Clubhouse notice boards) My name is David and I have been coming to the American Clubhouse for four years. I have recently had a cockerpoo puppy called Lucky. The Newsletter Online Lucky is now seven months old and is a proper The current newsletter and back issues are little ball of fun. I had Lucky to help me go to now available online. Scan this QR Code to be new places because I get anxious. I take Lucky taken to the webpage where you can view the to Leicester to do his special puppy training so newsletters. -

Annual Report 2006 Our Vision Is to Remove the Boundaries of Connectivity

Your Satellite Connection to the World Annual Report 2006 Our vision is to remove the boundaries of connectivity Contents 02 SES in brief 44 Financial review by management 04 Chairman’s statement 06 President and CEO’s statement 49 Consolidated financial statements 08 Recent developments 49 Report of the independent auditor 50 Consolidated income statement 10 Operations review 51 Consolidated balance sheet 10 Market review 52 Consolidated statement of cash flow 12 Positioning for growth 53 Consolidated statement of changes in 13 Satellite infrastructure business shareholders’ equity 13 EMEA 54 Notes to the consolidated financial statements 16 Americas 18 Other regions 88 SES S.A. annual accounts 23 Satellite services business 88 Report of the independent auditor 23 EMEA 89 Balance sheet 26 Americas and other regions 90 Profit and loss account 90 Statement of changes in shareholders’ equity 29 Corporate governance 91 Notes to the SES S.A. accounts 29 SES shareholders 30 Chairman’s report on corporate governance 100 Other information 30 The Annual General Meeting of shareholders 100 Shareholder information 31 The Board of Directors and its Committees 100 Companies of the Group 32 The Members of the Board of Directors 34 Committees of the Board of Directors 35 The Executive Committee 35 Remuneration 36 The Members of the Executive Committee 37 External auditor 38 Internal control procedures 39 Human Resources 40 Investor Relations 40 Our corporate social responsibility policy Designed and produced by: greymatter williams and phoa Printed -

Service Directory

Service Directory Version 16: June 2019 This directory is managed and updated by the Programme Team. Email any: changes, amendments, updates or additions to: [email protected] Organisations/services are grouped into categories and can be accessed directly from the contents page with one click. 1 Contents Principles .................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Vision ......................................................................................................................................................................... 6 TRAINING SERVICES ................................................................................................................................... 7 Expert Citizens C.I.C ....................................................................................................................................................... 7 Olive Branch (Staffordshire Fire and Rescue Service) .................................................................................................... 7 Safeguarding Children Partnership Board ...................................................................................................................... 8 Voices ............................................................................................................................................................................. 8 SERVICES AND SUPPORT ...................................................................................................................... -

Kenyon Collegian Archives

Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange The Kenyon Collegian Archives 4-9-1998 Kenyon Collegian - April 16, 1998 Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/collegian Recommended Citation "Kenyon Collegian - April 16, 1998" (1998). The Kenyon Collegian. 545. https://digital.kenyon.edu/collegian/545 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Kenyon Collegian by an authorized administrator of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. lite SwpBfi Mfa$$i Volume CXXV, Number 2 1 ESTABLISHED 1856 Thursday, April 16, 1998 Students petition to 'save' Jan Thomas reer in the Washington, D.C., area BY DAVID SHARGEL ment. Jan Thomas has made after Kenyon, said "Kenyon was News Editor comps and honors projects pos- 'I have had tremendous support from students never 'temporary' in her mind; sible for students by offering her the Kenyon community for Visiting Assistant Professor advice and support," said Eric and other members of it was the logical extension of of Sociology Jan E. Thomas will Smith '99, who organized to peti- which I am very grateful and very touched.' where my career was headed." leave Kenyon shortly after the cur- tion to "save" Thomas. "I have had two wonderful Jan Thomas said Tho- rent academic year ends when her 37 1 signatures were obtained, years here at Kenyon," have tremendous sup- contract expires. Students, how- according to Shane Goldsmith mas. -

April 23, 1998

Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange The Kenyon Collegian College Archives 4-16-1998 Kenyon Collegian - April 23, 1998 Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/collegian Recommended Citation "Kenyon Collegian - April 23, 1998" (1998). The Kenyon Collegian. 546. https://digital.kenyon.edu/collegian/546 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College Archives at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Kenyon Collegian by an authorized administrator of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Volume CXXV, Number 22 ESTABLISHED 1856 Thursday, April 23, 1998 Trustees hold spring meeting this weekend BYSETH GOLDEN ulty promotions and reappoint working on this year, the trustee puter system tor the College and hear a report on the status of prelimi- the to a new Staff Reporter ments, will hear a report on the committee will have a Relations division to support conversion computer new Minority Dissertation Fel- nary discussion with representa- the campaign, the information system for admissions," said The Board of Trustees will lowship program, and will be tives from the Task Force on Al- resources offered to Kenyon Anderson. meet Saturday to discuss a di- talking to several faculty com- cohol and Other Drugs on the from the Ohio Five and President Robert A. Oden, verse agenda with liaisons be- mittee chairs about their Work Kenyon College campus. The fo- OhioLINK consortia, and the re- Jr. offered insight into the ac- tween the college and each of its this year," said Provost cus of that discussion will be the cently announced reorganization tivities of yet two more com- committees.