Comics on the Streets of Brussels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Por La Olimpiada 92

BIBLIOTECA DE BARAÑAIN BARAÑAINGO LIBURUTEGIA CÓMICS INFANTILES HAUR-KOMIKIAK NOVIEMBRE 2008 2008ko AZAROA ¿Te gusta el cómic? ¿Te has muerto de risa alguna vez con Asterix y Obelix, con Mortadelo, con los Simpson y otros mil personajes locos, locos, locos? En esta guía puedes ver algunos cómics infantiles que tenemos en la biblioteca de Barañain. Queremos sumarnos así a la campaña “Galaxia-Cómic” puesta en marcha por el Departamento de Educación para animar a leer en familia. El cómic, con esa mezcla de imágenes, texto y a menudo (aunque no siempre) humor, es un género que ha atraído desde siempre a los niños y a los jóvenes. Si le preguntas a cualquier persona mayor a la que le guste leer cómo se inició su afición por la lectura es muy probable que te diga que empezó de niño leyendo cómics. Por eso nos parece acertada esta iniciativa y te invitamos a venir a la biblioteca para que puedas elegir los cómics que más te gusten, leerlos aquí o, si prefieres, llevártelos a casa y leerlos tranquilamente este otoño. Te esperamos. Atsegin duzu komikia? Barrez lehertu al zara noizbait Asterixekin eta Obelixekin, Mortadelorekin, Simpson senitartekoekin, edota beste hainbat eta hainbat pertsonaia ero, ero, erorekin? Gida honetan Barañaingo liburutegian dauzkagun haurrentzako zenbait komiki aurki ditzakezu. Horixe da Nafarroako Gobernuaren Hezkuntza Sailak abian jarritako “Galaxia-komiki” kanpainarekin bat egiteko gure modua, hain zuzen ere senitartean irakurtzeko zaletasuna piztu asmoz. Komikia, irudiez, testuez eta sarritan –baina ez beti- umorez jantzirik, haurrak eta gazteak betidanik erakarri dituen generoa da. Irakurtzeko zaletasuna duen edozein pertsona helduri huraxe nola piztu zitzaion galdetzen badiozu, litekeena da erantzutea umetatik komikiak irakurtzen hasi zela. -

The Scorpion: Devils Mark V. 1 Free

FREE THE SCORPION: DEVILS MARK V. 1 PDF Stephen Desberg,Marini | 96 pages | 30 Nov 2008 | CINEBOOK LTD | 9781905460625 | English | Ashford, United Kingdom GCD :: Issue :: The Scorpion #1 - The Devil's Mark Cookies are used to provide, analyse and improve our services; provide chat tools; and show you relevant content on advertising. You can learn more about our use of cookies here. Are you happy to accept all cookies? Accept all Manage Cookies Cookie Preferences We use cookies and similar tools, including those used by approved third parties collectively, "cookies" for the purposes described below. You can learn more about how we plus approved third parties use cookies and how to change your settings by visiting the Cookies notice. The choices you make here will apply to your interaction with this service on this device. Essential We use cookies to provide our servicesfor example, to keep track of items stored in your shopping basket, prevent fraudulent activity, The Scorpion: Devils Mark v. 1 the security of our services, keep track of your specific preferences e. These cookies are necessary to provide our site and services and therefore cannot be disabled. For example, we use cookies to conduct research and diagnostics to improve our content, products and services, and to measure and analyse the performance of our services. Show less Show more Advertising ON OFF We use cookies to serve you certain types of adsincluding ads relevant to your interests on Book Depository and to work with approved third parties in the process of delivering ad content, including ads relevant to your interests, to measure the effectiveness of their ads, and to perform services on behalf of Book The Scorpion: Devils Mark v. -

The Swiss Comic Strip in Brussels

From 4 February until 18 May 2014 At the Belgian Comic Strip Center Cosey, A la recherche de Peter Pan, Le Lombard The Swiss comic strip in Brussels The geography of the European comic strip rises to some impressive heights – among them Derib, Cosey and Zep – and not everyone realizes that these authors are not in fact Belgian but Swiss. This exhibition at CBBD, staged with the assistance of the Swiss Embassy in Brussels and the Centre BD in Lausanne, therefore reestablishes a few geographical truths and showcases the talents of today’s creators of the Swiss comic strip. Curator : JC De la Royère In collaboration with the Embassy of Switzerland in Belgium and the comic strip center of the city of Lausanne. With the support of the Brussels Capital Region Belgian Comic Strip Center Rue des Sables, 20 - 1000 Brussels (Belgium) Open every day (except on Monday) from 10 a.m. till 6 p.m. Tel: +32 (0)2 219 19 80 - www.comicscenter.net - [email protected] Press-info: Willem De Graeve: [email protected] - +32 (0)2 210 04 33 or www.comicscenter.net/en/press, login: comics + password: smurfs The Swiss comic strip in Brussels An exhibition by the Belgian Comic Strip Center Curator : JC De la Royère Scenography : Jean Serneels Texts: JC De la Royère Translations: Bureau Philotrans Corrections : Tine Anthoni and Marie-Aude Piavaux Management of original artwork : Nathalie Geirnaert and Dimitri Bogaert Graphic design : Pierre Saysouk Photogravure : Sadocolor Framing: AP Frame, Marie Van Eetvelde Production: Jean Serneels and the team of the Belgian Comicscenter Communication: Valérie Constant and Willem De Graeve The Belgian Comic Strip Center wishes to thank Cuno Affolter, Siro Beltrametti, Anne Broodcoorens, Jean-Claude Camano, Armelle Casier, S.E. -

Bruxelles, Capitale De La Bande Dessinée Dossier Thématique 1

bruxelles, capitale de la bande dessinée dossier thématique 1. BRUXELLES ET LA BANDE DESSINÉE a. Naissance de la BD à Bruxelles b. Du héros de BD à la vedette de cinéma 2. LA BANDE DESSINÉE, PATRIMOINE DE BRUXELLES a. Publications BD b. Les fresques BD c. Les bâtiments et statues incontournables d. Les musées, expositions et galeries 3. LES ACTIVITÉS ET ÉVÈNEMENTS BD RÉCURRENTS a. Fête de la BD b. Les différents rendez-vous BD à Bruxelles c. Visites guidées 4. SHOPPING BD a. Adresses b. Librairies 5. RESTAURANTS BD 6. HÔTELS BD 7. CONTACTS UTILES www.visitbrussels.be/comics BRUXELLES EST LA CAPITALE DE LA BANDE DESSINEE ! DANS CHAQUE QUARTIER, AU DÉTOUR DES RUES ET RUELLES BRUXELLOISES, LA BANDE DESSINÉE EST PAR- TOUT. ELLE EST UNE FIERTÉ NATIONALE ET CELA SE RES- SENT PARTICULIÈREMENT DANS NOTRE CAPITALE. EN EFFET, LES AUTEURS BRUXELLOIS AYANT CONTRIBUÉ À L’ESSOR DU 9ÈME ART SONT NOMBREUX. VOUS L’APPRENDREZ EN VISITANT UN CENTRE ENTIÈREMENT DÉDIÉ À LA BANDE DESSINÉE, EN VOUS BALADANT AU CŒUR D’UN « VILLAGE BD » OU ENCORE EN RENCON- TRANT DES FIGURINES MONUMENTALES ISSUES DE PLUSIEURS ALBUMS D’AUTEURS BELGES… LA BANDE DESSINÉE EST UN ART À PART ENTIÈRE DONT LES BRUX- ELLOIS SONT PARTICULIÈREMENT FRIANDS. www.visitbrussels.be/comics 1. BRUXELLES ET LA BANDE DESSINEE A. NAISSANCE DE LA BD À BRUXELLES Raconter des histoires à travers une succession d’images a toujours existé aux quatre coins du monde. Cependant, les spéciali- stes s’accordent à dire que la Belgique est incontournable dans le milieu de ce que l’on appelle aujourd’hui la bande dessinée. -

Hergé and Tintin

Hergé and Tintin PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Fri, 20 Jan 2012 15:32:26 UTC Contents Articles Hergé 1 Hergé 1 The Adventures of Tintin 11 The Adventures of Tintin 11 Tintin in the Land of the Soviets 30 Tintin in the Congo 37 Tintin in America 44 Cigars of the Pharaoh 47 The Blue Lotus 53 The Broken Ear 58 The Black Island 63 King Ottokar's Sceptre 68 The Crab with the Golden Claws 73 The Shooting Star 76 The Secret of the Unicorn 80 Red Rackham's Treasure 85 The Seven Crystal Balls 90 Prisoners of the Sun 94 Land of Black Gold 97 Destination Moon 102 Explorers on the Moon 105 The Calculus Affair 110 The Red Sea Sharks 114 Tintin in Tibet 118 The Castafiore Emerald 124 Flight 714 126 Tintin and the Picaros 129 Tintin and Alph-Art 132 Publications of Tintin 137 Le Petit Vingtième 137 Le Soir 140 Tintin magazine 141 Casterman 146 Methuen Publishing 147 Tintin characters 150 List of characters 150 Captain Haddock 170 Professor Calculus 173 Thomson and Thompson 177 Rastapopoulos 180 Bianca Castafiore 182 Chang Chong-Chen 184 Nestor 187 Locations in Tintin 188 Settings in The Adventures of Tintin 188 Borduria 192 Bordurian 194 Marlinspike Hall 196 San Theodoros 198 Syldavia 202 Syldavian 207 Tintin in other media 212 Tintin books, films, and media 212 Tintin on postage stamps 216 Tintin coins 217 Books featuring Tintin 218 Tintin's Travel Diaries 218 Tintin television series 219 Hergé's Adventures of Tintin 219 The Adventures of Tintin 222 Tintin films -

Download the Expanded Digital Edition Here

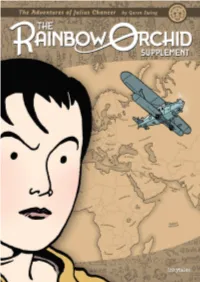

Spring 1999 December 2002 April 2002 February 2003 May 2003 September 2003 November 2003 October 2004 March 2005 October 2003 November 2007 August 2009 July 2010 April 2012 September 2012 September 2010 April 2011 June 2012 June 2012 November 2012 November 2012 November 2012 January 2013 January 2013 January 2013 I created The Rainbow Orchid because making comics is such hard work that I wanted to write and draw one that I could be absolutely certain at least one person would really like – that person being me. It is steeped in all the things I love. From the adventure stories of H. Rider Haggard, Jules Verne and Arthur Conan Doyle I took the long build-up to a fantastic element, made all the more amazing because the characters are immersed in the ‘real world’ for so much of the story. From the comics medium I dipped my pen into the European tradition of Hergé, Edgar P. Jacobs, Yves Chaland and the descendents of their ligne claire legacy, along with the strong sense of environment – a believable world – from Asterix and Tintin. Yet I wanted characters and a setting that were very strongly British, without being patriotic. Mixed into all this is my fondness for an involving and compelling plot, and artistic influences absorbed from a wealth of comic artists and illustrators, from Kay Neilsen to Bryan Talbot, and a simple love of history and adventure. No zombies, no bikini-clad gun-toting nubiles, and no teeth-gritting ... grittiness. Just a huge slice of pure adventure, made to go with a big mug of tea. -

Schorpioen 02. Het Geheim Van De Paus Gratis Epub, Ebook

SCHORPIOEN 02. HET GEHEIM VAN DE PAUS GRATIS Auteur: Enrico Marini Aantal pagina's: 48 pagina's Verschijningsdatum: none Uitgever: none EAN: 9789067935876 Taal: nl Link: Download hier De Schorpioen - 02 Het geheim van de paus - herdruk De sinistere prelaat hecht bijzondere waarde aan het elimineren van de Schorpioen. Trebaldi laat zijn oog vallen op Meja¿, een verleidelijke Egyptische gifmengster, om het door de duivel getekende wezen te executeren Wees de eerste die een beoordeling schrijft! Deel je mening met de wereld, schrijf je klanten beoordeling en verdien Archonia punten! Indien je nog niet bekend bent met Archonia punten, kan je er hier meer over leren. US - Archonia. Je winkelmandje 0 artikelen - EUR 0. Voeg toe aan mandje. Koop dit en krijg 20 Archonia Punten. Uitgebreid zoeken. Tonen als: Tegels Lijst. Toon oplopend. De schorpioen Hij wil weten wat er van hun kind geworden is. Maar de zigeunerin is heel handig met vergiften en ze aarzelt Bekijk exemplaren. Schorpioen De gebeurtenissen spelen zich af als de Schorpioen nog jong is ; een avonturier, een rokkenjager en een schatgraver, voor wie de dood niet meer is dan een spel, dat soms veel geld oplevert, Van jager wordt De bijzondere woorden van Gioia is een origineel, overrompelend en geestig debuut van de jonge, megapopulaire docent Enrico Galiano. De bijzondere woo Olivier Varese is verslaggever zonder grenzen. En, zoals dat gaat in spionageverhalen, niets is wat het lijkt. Hoewel één van zijn eerste boeken teken Het laatste deel van Olivier Varese, verslaggever zonder grenzen! Het laatste nieuws en aanbiedingen van Scheltema ontvangen? Schrijf u dan hieronder in voor onze nieuwsbrief. -

GUIDA Alla STREET ART Di BRUXELLES

GUIDA alla STREET ART di BRUXELLES GUIDA alla STREET ART di BRUXELLES www.inviaggioconlebrioches.com Percorso dei murales a tema fumetti per le vie di Bruxelles. Di seguito trovi l'elenco dei murales da me scoperti con foto, indirizzo per raggiungerli e una breve trama del fumetto. L'ordine è stato pensato in modo logico per collegarli tutti uno dopo l'altro in modo tale da impiegarci il minor tempo possibile. Il centro di Bruxelles è apparentemente piccolino perciò vi consiglio, soprattutto se non hai molto tempo, di noleggiare una bicicletta Villo!. Per saperne di più puoi leggere il mio articolo: Come noleggiare una bicicletta Villo! Il percorso unisce 39 murales per un totale di 13 km. N. Nome Immagine Indirizzo Descrizione Autore: Stéphane Desberg Artista: Marini Treurenberg 16, Bruxelles, Scorpion deve il suo nome allo scorpione tatuato 1 Scorpion Belgio sulla sua spalla destra. Il suo acerrimo nemico è Trebaldi un cardinale con l'ambizione di diventare Papa. La storia, ambientata nel XVIII venne creata da Desberg. Gaston Lagaffe è l'antieroe o l'eroe senza impiego. E' un ragazzo di quasi vent'anni e il suo talento è quello di evitare di fare qualsiasi lavoro, Boulevard Pachéco 43, 2 Gaston Lagaffe e indulgere invece in hobby o sonnellini mentre Bruxelles, Belgio intorno a lui succede di tutto. Non solo combina un sacco di pasticci e a questo deve il nome LaGaffe. Il museo del fumetto, chiamato Musée de la Bande Dessinée, è uno dei luoghi da non perdere. Museo de la Bande Rue des Sables 20, Bruxelles, Il museo racconta la storia, le tecniche e tipologie 3 Dessinée Belgio di fumetto. -

PASTAUD Maison De Ventes Aux Enchères

PASTAUD Maison de ventes aux enchères Dimanche 17 février 2018 à 14h15 Hôtel des ventes 5 rue Cruche d’Or 87000 LIMOGES FIGURINES ET ALBUMS DE BANDE DESSINÉE Collection de M. et Mme D*** EXPOSITIONS : Vendredi 15 février de 14h à 18h | Samedi 16 février de 10h à 12h | Dimanche 17 février de 10h à 12h © Hergé-Moulinsart 2019 Vente en ligne en direct sur www.interencheres-live.com Toutes les photos sont consultables sur : www.interencheres.com /87001 www.gazette-drouot.com www.poulainlivres.com PASTAUD Cabinet POULAIN Maison de ventes aux enchères Experts 5, rue Cruche d’Or 87000 LIMOGES Elvire Poulain-Marquis : 06 72 38 90 90 Tél. : 05 55 34 33 31 / 06 50 614 608 Pierre Poulain : 06 07 79 98 61 Fax : 05 55 32 59 65 1, cité Bergère 75009 PARIS E-mail : [email protected] Tél : 01 44 83 90 47 Me Paul Pastaud - Commissaire-priseur habilité Mail : [email protected] Agrément 2002-322 du 11/07/2002 www.poulainlivres.com 1 OÙ ENVOYER VOS ORDRES D’ACHAT ? 1. Par mail : 2. Par fax : 3. Par courrier : [email protected] à la maison de ventes : Hôtel des ventes et/ou [email protected] 05 55 32 59 65 5 rue cruche d’Or 87000 Limoges Les ordres d’achat par fax ou internet devront être envoyés avant le matin de la vente à 9 h 30 ; les ordres d’achats ou demandes d’enchères par téléphone envoyés ensuite risquant de ne pas pouvoir être pris en compte. Il est conseillé de nous contacter afin de confirmer la bonne réception de vos ordres d’achat. -

P Ar C Ourez Les Librairies Spé Cialisées Du Centre-Ville

PARCOUREZ LES PARCOUREZ LIBRAIRIES SPÉCIALISÉES DU CENTRE-VILLE www.bd-bruxelles.be LES FRESQUES DU PARCOURS BD LE PARCOURS BD AU CENTRE-VILLE EDITO (voir plan au verso, 1 à 46 ) DE BRUXELLES 1 Le grand loup qui porte le mouton | Dominique Goblet | Rue Pélikan 2 Cubitus | Dupa | Rue de Flandre CENTRE-VILLE, DESTINATION BD 3 Billy the Cat | Colman & Desberg | Rue d’Ophem 4 Bob & Bobette | Willy Vandersteen | Rue de Laeken 5 La Vache | Johan de Moor | Rue du Damier Découvrir ses rues dans les foulées des plus 6 Black & Mortimer | Jacobs | rue du Houblon 8 Les Rêves de Nick | Herman | Rue des Fabriques célèbres héros de bande dessinée, c’est l’invitation 9 Cori | Bob de Moor | Rue des Fabriques 10 Tour à Plomb | Zidrou | Rue de l’Abattoir que fait Bruxelles à tous les amoureux du 9e art. 11 Lucky Luke | Morris | Rue de la Buanderie 12 Astérix & Obélix | Goscinny & Uderzo | Rue de la Buanderie Une expression artistique dont notre plat pays peut 13 In my Area | Lucy McKenzie | Rue des Chartreux 14 L’Ange de Sambre | Yslaire | Rue des Chartreux s’enorgueillir d’avoir vu naître ses talents les plus 15 Gaston Lagaffe | Franquin | Rue de l’Ecuyer 16 Le Scorpion | Marini | Treurenberg fameux, et dont notre ville est devenue à n’en pas 17 Néron | Marc Sleen | Place St Géry La Ville de Bruxelles accorde une attention particulière 18 Ducobu | Godi | Rue des 6 Jetons douter le chef-lieu. Une capitale où les férus du genre 19 LGBT | Ralf König | Rue de la Chaufferette à la riche et dynamique tradition belge de la bande 20 Le Passage | Schuiten | Rue Marché au Charbon ont désormais leur ‘’quartier général’’. -

Suske En Wiske Junior - Ijs Cool Gratis

SUSKE EN WISKE JUNIOR - IJS COOL GRATIS Auteur: Willy Vandersteen Aantal pagina's: 64 pagina's Verschijningsdatum: none Uitgever: none EAN: 9789002240720 Taal: nl Link: Download hier Junior Suske en Wiske - Ijs-cool - 1e druk sc Neem je favoriete striphelden overal mee naar toe. Spike and suzy u. Suske en wiske bob and bobette or spike and suzy in the uk, willy and wanda suske en wiske comic book in america, bob and bobette in france and israel suske en wiske comic book is a long- running since flemish comic book series. The regular edition has a red linen cover. Book mint condition, cover with some scrapes on the left side on the back. The adventures of the suske en wiske comic book inseparable child heroes suske and wiske were the reason some children sneakily read well into the night with the help of a flashlight. Pdf 13 suske en wiskede sissende sampa - Discover and save! Uitgegeven in opdracht van de efteling ter gelegenheid van de 75e verjaar. The story was first written and drawn by willy vandersteen in and published in several newspapers. For this subscribers special, we will be taking a look at the suske en wiske: sony- san comic book, and this comic book is a very cool collector' s item for sony fans! Reading from left to right, they are: tante sidonia wiske' s aunt , wiske, lambik a pompous but good- hearted friend of. Hurry - limited offer. Money back guarantee! Here a tribute to a special dutch comic book suske en wiske bondage- addicted asked me for! Ontdek je strips vanaf nu op pc, tablet of smartphone! See more ideas about comic books, comic book cover, comics. -

At a Glance General Information NEIGHBOURING COUNTRIES POPULATION CAPITAL Brussels 11.099.554 Inhabitants

at a glance General information NEIGHBOURING COUNTRIES POPULATION CAPITAL Brussels 11.099.554 inhabitants POPULATION DENSITY OFFICIAL LANGUAGES France Dutch Germany The Netherlands 363 inhab./km² Luxembourg French SURFACE AREA CURRENCY German 30.528 km² € Euro 1 3 4 6 1. St. Peter’s Church, Leuven 2. Citadel of Dinant 3. Bruges 4. Belfry, Tournai 5. Bouillon 6. Rue des Bouchers, Brussels 2 5 Belgium - a country of regions 1 2 Belgium is a federal state made up of three Communities (the Flemish Community, the French Community and the German- speaking Community) and three regions (the Brussels-Capital Region, the Flemish Region and the Walloon Region). The main federal institutions are the federal government and 3 the federal parliament, and the Communities and Regions also have their own legislative and executive bodies. The principal powers of the three Communities in Belgium, which are delimited on linguistic grounds, relate to education, culture, youth support and certain aspects of health policy. The three Regions have powers for ‘territorial issues’, such as public works, agriculture, employment, town and country 4 planning and the environment. 6 5 1. Flemish Region 2. Brussels-Capital Region 3. Walloon Region 4. Flemish Community 5. French Community 6. German-speaking Community The Belgian monarchy Belgium is a constitutional monarchy. King Philippe, the current monarch, is the seventh King of the Belgians. In the political sphere the King does not wield power of his own but acts in consultation with government ministers. In performing his duties, the King comes into contact with many representatives of Belgian society. The King and Queen and the other members of the Royal Family also represent Belgium abroad (state visits, eco- nomic missions and international meetings), while at home fostering close relations with their citizens and promoting public and private initiatives that make a contribution to improving society.