Our First Radio President

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Motion Film File Title Listing

Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum (714) 983 9120 ◦ http://www.nixonlibrary.gov ◦ [email protected] MOTION FILM FILE ● MFF-001 "On Guard for America: Nixon for U.S. Senator TV Spot #1" (1950) One of a series of six: On Guard for America", TV Campaign spots. Features Richard M. Nixon speaking from his office" Participants: Richard M. Nixon Original Format: 16mm film Film. Original source type: MPPCA. Cross Reference: MVF 47 (two versions: 15 min and 30 min);. DVD reference copy available ● MFF-002 "On Guard For America: Nixon for U.S. Senator TV Spot #2" (1950) One of a series of six "On Guard for America", TV campaign spots. Features Richard Nixon speaking from his office Participants: Richard M. Nixon Original Format: 16mm film Film. Original source type: MPPCA. DVD reference copy available ● MFF-003 "On Guard For America: Nixon for U.S. Senator TV Spot #3" (1950) One of a series of six "On Guard for America", TV campaign spots. Features Richard Nixon speaking from his office. Participants: Richard M. Nixon Original Format: 16mm film Film. Original source type: MPPCA. DVD reference copy available Monday, August 06, 2018 Page 1 of 202 Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum (714) 983 9120 ◦ http://www.nixonlibrary.gov ◦ [email protected] MOTION FILM FILE ● MFF-004 "On Guard For America: Nixon for U.S. Senator TV Spot #4" (1950) One of a series of six "On Guard for America", TV campaign spots. Features Richard Nixon speaking from his office. Participants: Richard M. Nixon Original Format: 16mm film Film. Original source type: MPPCA. -

Campaign and Transition Collection: 1928

HERBERT HOOVER PAPERS CAMPAIGN LITERATURE SERIES, 1925-1928 16 linear feet (31 manuscript boxes and 7 card boxes) Herbert Hoover Presidential Library 151 Campaign Literature – General 152-156 Campaign Literature by Title 157-162 Press Releases Arranged Chronologically 163-164 Campaign Literature by Publisher 165-180 Press Releases Arranged by Subject 181-188 National Who’s Who Poll Box Contents 151 Campaign Literature – General California Elephant Campaign Feature Service Campaign Series 1928 (numerical index) Cartoons (2 folders, includes Satterfield) Clipsheets Editorial Digest Editorials Form Letters Highlights on Hoover Booklets Massachusetts Elephant Political Advertisements Political Features – NY State Republican Editorial Committee Posters Editorial Committee Progressive Magazine 1928 Republic Bulletin Republican Feature Service Republican National Committee Press Division pamphlets by Arch Kirchoffer Series. Previously Marked Women's Page Service Unpublished 152 Campaign Literature – Alphabetical by Title Abstract of Address by Robert L. Owen (oversize, brittle) Achievements and Public Services of Herbert Hoover Address of Acceptance by Charles Curtis Address of Acceptance by Herbert Hoover Address of John H. Bartlett (Herbert Hoover and the American Home), Oct 2, 1928 Address of Charles D., Dawes, Oct 22, 1928 Address by Simeon D. Fess, Dec 6, 1927 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – Boston, Massachusetts, Oct 15, 1928 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – Elizabethton, Tennessee. Oct 6, 1928 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – New York, New York, Oct 22, 1928 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – Newark, New Jersey, Sep 17, 1928 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – St. Louis, Missouri, Nov 2, 1928 Address of W. M. Jardine, Oct. 4, 1928 Address of John L. McNabb, June 14, 1928 Address of U. -

Radio TV Mirror

JANICE GILBERT The girl who gave away MIRRO $3,000,000! ARTHUR GODFREY BROOK BYRON BETTY LU ANN SIMMS ANN GROVE ! ^our new Lilt home permaTient will look , feel and stay like the loveliest naturally curly hair H.1 **r Does your wave look as soft and natural as the Lilt girl in our picture? No? Then think how much more beautiful you can be, when you change to Lilt with its superior ingredients. You'll be admired by men . envied by women ... a softer, more charming you. Because your Lilt will look, feel and stay like naturally curly hair. Watch admiring eyes light up, when you light up your life with a Lilt. $150 Choose the Lilt especially made for your type of hair! plus tax Procter £ Gambles new Wt guiJ. H Home Permanent tor hard-to-wave hair for normal hair for easy-to-wave hair for children's hair — . New, better way to reduce decay after eating sweets Always brush with ALL- NEW IPANA after eating ... as the Linders do . the way most dentists recommend. New Ipana with WD-9 destroys tooth-decay bacteria.' s -\V 77 If you eat sweet treats (like Stasia Linder of Massa- Follow Stasia Linder's lead and use new Ipana regularly pequa, N. Y., and her daughter Darryl), here's good news! after eatin g before decay bacteria can do their damage. You can do a far better job of preventing cavities by Even if you can't always brush after eating, no other brushing after eatin g . and using remarkable new Ipana tooth paste has ever been proved better for protecting Tooth Paste. -

The President Also Had to Consider the Proper Role of an Ex * President

************************************~ * * * * 0 DB P H0 F E8 8 0 B, * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * The little-known * * story of how * a President of the * United States, Beniamin Harrison, helped launch Stanford law School. ************************************* * * * T H E PRESIDENT * * * * * * * * * * * * By Howard Bromberg, J.D. * * * TANFORD'S first professor of law was a former President of the United * States. This is a distinction that no other school can claim. On March 2, 1893, * L-41.,_, with two days remaining in his administration, President Benjamin Harrison * * accepted an appointment as Non-Resident Professor of Constitutional Law at * Stanford University. * Harrison's decision was a triumph for the fledgling western university and its * * founder, Leland Stanford, who had personally recruited the chief of state. It also * provided a tremendous boost to the nascent Law Department, which had suffered * months of frustration and disappointment. * David Starr Jordan, Stanford University's first president, had been planning a law * * program since the University opened in 1891. He would model it on the innovative * approach to legal education proposed by Woodrow Wilson, Jurisprudence Profes- * sor at Princeton. Law would be taught simultaneously with the social sciences; no * * one would be admitted to graduate legal studies who was not already a college * graduate; and the department would be thoroughly integrated with the life and * * ************************************** ************************************* * § during Harrison's four difficult years * El in the White House. ~ In 1891, Sena tor Stanford helped ~ arrange a presidential cross-country * train tour, during which Harrison * visited and was impressed by the university campus still under con * struction. When Harrison was * defeated by Grover Cleveland in the 1892 election, it occurred to Senator * Stanford to invite his friend-who * had been one of the nation's leading lawyers before entering the Senate * to join the as-yet empty Stanford law * faculty. -

Notre Dame Alumnus, Vol. 16, No. 06

The Archives of The University of Notre Dame 607 Hesburgh Library Notre Dame, IN 46556 574-631-6448 [email protected] Notre Dame Archives: Alumnus mfeii^^jg«;^<^;gs.^gj5«ggg^^ THE NOTRE DAME ALUMNUS /.. ^ "t^ , ^ i -^m-r '^•P\ if.v,VAY ?..- "^n -<-":-i}. i > "l^.*:- -'/f.^^^, Reunion dates: Si? JUNE 3 -m^^?^ «^.%-. 4 ^ 5 ' •> n> (See program inside] f| 174 The Notre Dame Alumnus May. 1938 sirrs The University acknowledges with deep gratitude the following gifts: From Mr. O. L. Rhoades, Siin Manufacturing Company, Chicago. A sun combustion tester, for the Department of Aeronautical Elngincering. From the Studdiafcer Corporation, South Bend. Two bound folio volumes of photostatic copies of dippings referring to the career of the late Knute Rockne. From: The Rev. John O'Brien, Yonkers, N. Y. Mr. Charles F. McTague^ Montdair, N. J. Mr. Edward L. Boyle, Sr., Duluth, Minn. Reference books for special libraries. From the Library of the University of Virginia. Forty-three volumes, for the College of Engineering. For the Rockne Mennorial E. F. Moran. M?: W. B. Moran, 74; J. R. Moran. Rev. J. A. McShane, Winnebago, Mmn. 10 •25: J. A. Moran. 10: and \V. H. Moran, Rev. Michael P. Seter, Evansville, Ind. ._ 10 Tulsa, Oklahoma $1,000 Rev. William Murray, Chicago, Illinois 10 E. T. Fleming, Dallas, Texas 500 Rev. John P. Donahue. Hopedale, Mass. 10 J. A. LaFortune, '18, Tulsa 500 Rev. John C. Vismara, Detroit, Michigan 10 A. \V. Leonard, •89--93. Tulsa 500 Rev. Martin J. Donlon, Brooklyn. N. Y. 10 J. \V. Simmons, Dallas. Texas 250 Rev. -

The Old Time Radio Club Established 1975

The Old Time Radio Club Established 1975 Number 355 December 2007 The fllustrated Pres« Membership Information Club Officers Club Membership: $18.00 per year from January 1 President to December 31. Members receive a tape library list Jerry Collins (716) 683-6199 ing, reference library listing and the monthly 56 Christen Ct. newsletter. Memberships are as follows: If you join Lancaster, NY 14086 January-March, $18.00; April-June, $14; July [email protected] September, $10; October-December, $7. All renewals should be sent in as soon as possible to Vice President & Canadian Branch avoid missing newsletter issues. Please be sure to notify us if you have a change of address. The Old Richard Simpson (905) 892-4688 Time Radio Club meets on the first Monday of the 960 16 Road RR 3 month at 7:30 PM during the months of September Fenwick, Ontario through June at St. Aloysius School Hall, Cleveland Canada, LOS 1CO Drive and Century Road, Cheektowaga, NY. There is no meeting during the month of July, and an Treasurer informal meeting is held in the month of August. Dominic Parisi (716) 884-2004 38 Ardmore PI. Anyone interested in the Golden Age of Radio is Buffalo, I\lY 14213 welcome. The Old Time Radio Club is affiliated with the Old Time Radio Network. Membership Renewals, Change of Address Peter Bellanca (716) 773-2485 Club Mailing Address 1620 Ferry Road Old Time Radio Club Grand Island, NY 14072 56 Christen Ct. [email protected] Lancaster, NY 14086 E-Mail Address Membership Inquires and OTR otrclub(@localnet.com Network Related Items Richard Olday (716) 684-1604 All Submissions are subject to approval 171 Parwood Trail prior to actual publication. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title A Soldier at Heart: The Life of Smedley Butler, 1881-1940 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6gn7b51j Author Myers, Eric Dennis Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles A Soldier at Heart: The Life of Smedley Butler, 1881 - 1940 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Eric Dennis Myers 2013 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION A Soldier at Heart: The Life of Smedley Butler, 1881 - 1940 by Eric Dennis Myers Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Joan Waugh, Chair The dissertation is a historical biography of Smedley Darlington Butler (1881-1940), a decorated soldier and critic of war profiteering during the 1930s. A two-time Congressional Medal of Honor winner and son of a powerful congressman, Butler was one of the most prominent military figures of his era. He witnessed firsthand the American expansionism of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, participating in all of the major conflicts and most of the minor ones. Following his retirement in 1931, Butler became an outspoken critic of American intervention, arguing in speeches and writings against war profiteering and the injustices of expansionism. His critiques represented a wide swath of public opinion at the time – the majority of Americans supported anti-interventionist policies through 1939. Yet unlike other members of the movement, Butler based his theories not on abstract principles, but on experiences culled from decades of soldiering: the terrors and wasted resources of the battlefield, ! ""! ! the use of the American military to bolster corrupt foreign governments, and the influence of powerful, domestic moneyed interests. -

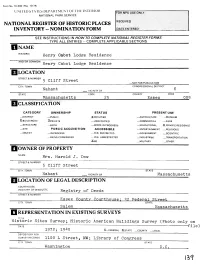

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATHS DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Henry Cabot Lodge Residence AND/OR COMMON Henry Cabot Lodge Residence 5 Cliff Street .NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Nahant VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 25 Essex 009 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC XOCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK _ STRUCTURE _BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X.PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE _ ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS _OBJECT _IN PROCESS _YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED _YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION -XNO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Mrs. Harold J. Dow STREET & NUMBER 5 Cliff Street CITY, TOWN STATE Nahant VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC Registry of Deeds STREETS NUMBER Essex County Courthouse: ^2 Federal Street CITY, TOWN STATE Salem Massachusetts I REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic Sites Survey; Historic American Buildings Survey (Photo only on DATE ————————————————————————————————————file) 1972; 19^0 X_FEDERAL 2LSTATE _COUNTY _J_OCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS 1100 L Street, NW; Library of Congress Washington D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _EXCELLENT -DETERIORATED —UNALTERED 3C ORIGINAL SITE X_QOOD —RUINS X_ALTERED _MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE This two-story, hip-roofed, white stucco-^covered, lavender- trimmed, brick villa is the only known extant residence associated with Henry Cabot Lodge. -

Open PDF File, 134.33 KB, for Paintings

Massachusetts State House Art and Artifact Collections Paintings SUBJECT ARTIST LOCATION ~A John G. B. Adams Darius Cobb Room 27 Samuel Adams Walter G. Page Governor’s Council Chamber Frank Allen John C. Johansen Floor 3 Corridor Oliver Ames Charles A. Whipple Floor 3 Corridor John Andrew Darius Cobb Governor’s Council Chamber Esther Andrews Jacob Binder Room 189 Edmund Andros Frederick E. Wallace Floor 2 Corridor John Avery John Sanborn Room 116 ~B Gaspar Bacon Jacob Binder Senate Reading Room Nathaniel Banks Daniel Strain Floor 3 Corridor John L. Bates William W. Churchill Floor 3 Corridor Jonathan Belcher Frederick E. Wallace Floor 2 Corridor Richard Bellingham Agnes E. Fletcher Floor 2 Corridor Josiah Benton Walter G. Page Storage Francis Bernard Giovanni B. Troccoli Floor 2 Corridor Thomas Birmingham George Nick Senate Reading Room George Boutwell Frederic P. Vinton Floor 3 Corridor James Bowdoin Edmund C. Tarbell Floor 3 Corridor John Brackett Walter G. Page Floor 3 Corridor Robert Bradford Elmer W. Greene Floor 3 Corridor Simon Bradstreet Unknown artist Floor 2 Corridor George Briggs Walter M. Brackett Floor 3 Corridor Massachusetts State House Art Collection: Inventory of Paintings by Subject John Brooks Jacob Wagner Floor 3 Corridor William M. Bulger Warren and Lucia Prosperi Senate Reading Room Alexander Bullock Horace R. Burdick Floor 3 Corridor Anson Burlingame Unknown artist Room 272 William Burnet John Watson Floor 2 Corridor Benjamin F. Butler Walter Gilman Page Floor 3 Corridor ~C Argeo Paul Cellucci Ronald Sherr Lt. Governor’s Office Henry Childs Moses Wight Room 373 William Claflin James Harvey Young Floor 3 Corridor John Clifford Benoni Irwin Floor 3 Corridor David Cobb Edgar Parker Room 222 Charles C. -

1 April 24Symbolizes the Beginning of the Young Turk Government's

April 24 symbolizes the beginning of the Young Turk government’s organized genocidal campaign to eliminate Armenians in the Ottoman Empire. On that day in 1915, the Ottoman Turkish government arrested some 200 Armenian community leaders, most of whom were later murdered. Background During the second half of the nineteenth century, the Armenian population of the decaying Ottoman Empire became the target of heightened persecution. This policy culminated in the Armenian Genocide. Conceived and carried out by the Young Turk regime from 1915 to 1923, the first genocide of the 20th century resulted in the deportation of nearly 2,000,000 Armenians, of whom 1,500,000 men, women, and children were killed, while the remaining 500,000 survivors were expelled from their homeland of 3,000 years. At the beginning of World War I, there were some 2,100,000 Armenians living in the Ottoman Empire. Following the Armenian Genocide, fewer than 100,000 declared Armenians remained in Turkey. A Proud Chapter in U.S. History American intervention prevented the full realization of Ottoman Turkey’s genocidal plan. In 1919, President Woodrow Wilson authorized Major General James Harbord, who served as General John J. Pershing’s Chief of Staff during World War I, to lead an American Military Mission to Armenia. Major General Harbord submitted his FACT SHEET FACT report from the U.S.S. Martha Washington that same year, which read in part: “mutilation, violation, torture and death have left their haunting memories in a hundred beautiful Armenian valleys, and the traveler in that region is seldom free from the evidence of this most colossal crime of all the ages.” The U.S. -

4 the AMERICAN and BRITISH CULTURAL APPROACHES The

4 THE AMERICAN AND BRITISH CULTURAL APPROACHES HOW DIFFERENT WAS Japan's cultural approach from those of the United States and Great Britain in the 1920S? Was the same pattern of Sino Japanese interaction reflected in Sino-American and Sino-British interaction during this period? In analyzing the American situation, the chapter first focuses on Sino-American interaction and then examines American views on how the remission could be best used. The British case is then examined in a similar fashion, followed by a comparison of the two ap proaches. THE AMERICAN APPROACH, 1924-1931 The Second American Remission and Sino-American Interaction In December 1908, the United States remitted a portion of its Boxer indem nity to support an educational program comprised of the Chinese Educa tional Mission and T singhua College. While this program continued into the 1920S, there were also calls for the United States to remit the remaining portion of its indemnity for similar purposes. This movement for total re mission was actively advocated by the chairman of the Senate Foreign Rela tions Committee, Henry Cabot Lodge. With the backing of the State De partment, Lodge introduced a resolution for total remission in May 1921. Although the resolution was passed by the Senate in August, it was stalled The American and British Cultural Approaches 93 in the House, whose members feared that approving such an act might en courage the European powers involved in World War I to press the United States for a. similar waiving of their war debts.l When the fear of such a linkage gradually ebbed over the next two years, Lodge re-introduced the remission resolution into Congress in December 1923. -

Dials and Channels David Sarnoff and His

Dials and Channels The Journal of the National Capital Radio & Television Museum 2608 Mitchellville Road Bowie, MD 20716-1392 (301) 390-1020 Vol. 25, No. 3 ncrtv.org September 2019 David Sarnoff and His RCA By Brian Belanger Introduction threw a tantrum. He ordered all copies of the first draft destroyed and rewrote sections himself. Book Along the stairway to the second floor of the critics were quick to comment on how over-the-top Museum are displayed about a dozen photos of laudatory the sanitized version was. It did not sell individuals that we felt were deserving of recognition well. for their roles in the history of radio and television. David Sarnoff’s photo is included. It is certainly A later and more balanced biography was authored appropriate that his story and how he shaped RCA, by Kenneth Bilby after Sarnoff’s death. Bilby was the Radio Corporation of America, be told in Dials Sarnoff’s public relations manager and a close and Channels. associate. This article relies heavily on that source. Any author outside of RCA intending to write a Sarnoff is a controversial figure. His supporters have Sarnoff biography who sought access to company called him a visionary and a genius, and are in awe of records would probably have received cooperation him, while critics have described him as a ruthless in proportion to how likely that author was to praise egotist. A case might be made for either label. I recognize Sarnoff’s shortcomings, yet I admire him for reasons that will become clear later in this article.