18C20-P2only-August

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Brief History of Christ Church MEDIEVAL PERIOD

A Brief History of Christ Church MEDIEVAL PERIOD Christ Church was founded in 1546, and there had been a college here since 1525, but prior to the Dissolution of the monasteries, the site was occupied by a priory dedicated to the memory of St Frideswide, the patron saint of both university and city. St Frideswide, a noble Saxon lady, founded a nunnery for herself as head and for twelve more noble virgin ladies sometime towards the end of the seventh century. She was, however, pursued by Algar, prince of Leicester, for her hand in marriage. She refused his frequent approaches which became more and more desperate. Frideswide and her ladies, forewarned miraculously of yet another attempt by Algar, fled up river to hide. She stayed away some years, settling at Binsey, where she performed healing miracles. On returning to Oxford, Frideswide found that Algar was as persistent as ever, laying siege to the town in order to capture his bride. Frideswide called down blindness on Algar who eventually repented of his ways, and left Frideswide to her devotions. Frideswide died in about 737, and was canonised in 1480. Long before this, though, pilgrims came to her shrine in the priory church which was now populated by Augustinian canons. Nothing remains of Frideswide’s nunnery, and little - just a few stones - of the Saxon church but the cathedral and the buildings around the cloister are the oldest on the site. Her story is pictured in cartoon form by Burne-Jones in one of the windows in the cathedral. One of the gifts made to the priory was the meadow between Christ Church and the Thames and Cherwell rivers; Lady Montacute gave the land to maintain her chantry which lay in the Lady Chapel close to St Frideswide’s shrine. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT of INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION in Re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMEN

USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 1 of 354 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION ) Case No. 3:05-MD-527 RLM In re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE ) (MDL 1700) SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMENT ) PRACTICES LITIGATION ) ) ) THIS DOCUMENT RELATES TO: ) ) Carlene Craig, et. al. v. FedEx Case No. 3:05-cv-530 RLM ) Ground Package Systems, Inc., ) ) PROPOSED FINAL APPROVAL ORDER This matter came before the Court for hearing on March 11, 2019, to consider final approval of the proposed ERISA Class Action Settlement reached by and between Plaintiffs Leo Rittenhouse, Jeff Bramlage, Lawrence Liable, Kent Whistler, Mike Moore, Keith Berry, Matthew Cook, Heidi Law, Sylvia O’Brien, Neal Bergkamp, and Dominic Lupo1 (collectively, “the Named Plaintiffs”), on behalf of themselves and the Certified Class, and Defendant FedEx Ground Package System, Inc. (“FXG”) (collectively, “the Parties”), the terms of which Settlement are set forth in the Class Action Settlement Agreement (the “Settlement Agreement”) attached as Exhibit A to the Joint Declaration of Co-Lead Counsel in support of Preliminary Approval of the Kansas Class Action 1 Carlene Craig withdrew as a Named Plaintiff on November 29, 2006. See MDL Doc. No. 409. Named Plaintiffs Ronald Perry and Alan Pacheco are not movants for final approval and filed an objection [MDL Doc. Nos. 3251/3261]. USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 2 of 354 Settlement [MDL Doc. No. 3154-1]. Also before the Court is ERISA Plaintiffs’ Unopposed Motion for Attorney’s Fees and for Payment of Service Awards to the Named Plaintiffs, filed with the Court on October 19, 2018 [MDL Doc. -

Richard Hooker

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com 2,or. - Qºbe (5teat Qbutchmen 56tíč3 EDITED by VERNON STALEY RICHARD HOOKER ** - - - ---- -- ---- - -- ---- ---_ RICHARD HOOKER. Picture from National Portrait Gallery, by perm 13.5 to ºr 0. 'f Macmillan & Co. [Frontispiece. ICHARD as at HOOKER at By VERNON STALEY PROVOST OF THE CATHEDRAL CHURCH of ST. ANDREW, INVERNESS ... • * * * LONDON: MASTERS & CO., LTD. 1907 78, NEW BOND STREET, w. \\ \ \ EDITOR'S PREFACE It has been recently said by one accustomed to weigh his words, “I do not think it can be doubted that in the early years of Queen Elizabeth a large part, numerically the larger part, of the clergy and laity who made up the Church of England was really Catholic at heart, though the Reformers made up for deficiency of numbers by energy and force of conviction.” And again, “When Elizabeth came to the throne, the nation was divided between a majority of more or less lukewarm Catholics no longer to be called Roman, and a minority of ardent Protestants, who were rapidly gaining—though they had not quite gained—the upper hand. The Protestantism generally was of a type current in South West Germany and Switzerland, but the influence of Calvin was increasing every day.” Dr. Sanday here uses the term “Catholics,” in the * Dr. Sanday, Minutes of Evidence taken before The Royal Com †: on Ecclesiastical Discipline, 1906. Vol. III. p. 20, §§ 16350, V b 340844 vi EDITOR'S PREFACE sense of those who were attached to the old faith and worship minus certain exaggerations, but who disliked the Roman interference in England. -

Angliæ Notitia, Or, the Present State of England with Divers Remarks Upon

s/3/ AKGLIM N0TIT1A: jyhn or,the/w/ ENGLAND: With Divers REMARK S UPON The Ancient State thereof. By EDW. CHAMBERLATNE, Doctor of Laws. The Nineteenth Edition, with great Additions and Improvements. In Three PARTS. Sfart am quam naff us efi banc ornni. LONDON, Printed by T. Hodgkin, for R. Cbiftveil, M.Gillyfioretr, S. Sonith and B. Watford, M. Wotton, G. Sanbridgs, and B. Toots, 1700. Moft Excellent Majefty, william m. K I N G O F GreauBritain, Frame3 and Ireland’ Defender of the Truly Ancient, C.i- tholick, and Apoftolick Faith. This Nineteenth Impreffton of the (P RE¬ SENT STATE of ENG¬ LAND is Humbly Dedicated By Edw. Chamberlayne, Doftor of Laws. THE CONTENTS. A Defeription of England in general. Chap. X. Of its Name, Climate, Dimenfms, Di- Chap. II. Of the Bifhopricks of England. Chap. III. A Defcriftm of the feveral Counties tf England and Wales. Chap. IV. Of its Air, Soil, and Commodities. Chap. V. Of its Inhabitants, their Number, Language, and Character. Chap. VI. Of Religion. Chap. VII. Of Trade. GOVERNMENT. Chap. I. QF the Government of England in ge- Chap.II. Of the KJng of England, and therein of his Name, Title, Pcrfon, Office, Supremacy and Sove¬ reignty, Potter and Prerogative, Dominions, Strength, Patrimony, Arms and Ref fell. Chap. III. Of the SucceJJion to the Croton of England, and the King’s Minority, Incapacity and Abjence. Chap. IV. Of the prefent King of England ; and therein of his Birth, Name, Simame, and Genealogy, Arms, Title, Education, Marriage, Exploits, and Accef- fiyn to the Crown of England. -

Restoration, Religion, and Revenge Heather Thornton Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2005 Restoration, religion, and revenge Heather Thornton Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Thornton, Heather, "Restoration, religion, and revenge" (2005). LSU Master's Theses. 558. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/558 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RESTORATION, RELIGION AND REVENGE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History By Heather D. Thornton B.A., Lousiana State University, 1999 M. Div., Golden Gate Baptist Theological Seminary, 2002 December 2005 In Memory of Laura Fay Thornton, 1937-2003, Who always believed in me ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank many people who both encouraged and supported me in this process. My advisor, Dr. Victor Stater, offered sound criticism and advice throughout the writing process. Dr. Christine Kooi and Dr. Maribel Dietz who served on my committee and offered critical outside readings. I owe thanks to my parents Kevin and Jorenda Thornton who listened without knowing what I was talking about as well as my grandparents Denzil and Jo Cantley for prayers and encouragement. -

Episcopal Tombs in Early Modern England

Jnl of Ecclesiastical History, Vol. 55, No. 4, October 2004. f 2004 Cambridge University Press 654 DOI: 10.1017/S0022046904001502 Printed in the United Kingdom Episcopal Tombs in Early Modern England by PETER SHERLOCK The Reformation simultaneously transformed the identity and role of bishops in the Church of England, and the function of monuments to the dead. This article considers the extent to which tombs of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century bishops represented a set of episcopal ideals distinct from those conveyed by the monuments of earlier bishops on the one hand and contemporary laity and clergy on the other. It argues that in death bishops were increasingly undifferentiated from other groups such as the gentry in the dress, posture, location and inscriptions of their monuments. As a result of the inherent tension between tradition and reform which surrounded both bishops and tombs, episcopal monuments were unsuccessful as a means of enhancing the status or preserving the memory and teachings of their subjects in the wake of the Reformation. etween 1400 and 1700, some 466 bishops held office in England and Wales, for anything from a few months to several decades.1 The B majority died peacefully in their beds, some fading into relative obscurity. Others, such as Richard Scrope, Thomas Cranmer and William Laud, were executed for treason or burned for heresy in one reign yet became revered as saints, heroes or martyrs in another. Throughout these three centuries bishops played key roles in the politics of both Church and PRO=Public Record Office; TNA=The National Archives I would like to thank Craig D’Alton, Felicity Heal, Clive Holmes, Ralph Houlbrooke, Judith Maltby, Keith Thomas and the anonymous reader for this JOURNAL for their comments on this article. -

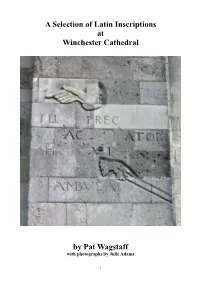

A SELECTION of LATIN INSCRIPTIONS at WINCHESTER CATHEDRAL by Pat Wagstaff

A Selection of Latin Inscriptions at Winchester Cathedral by Pat Wagstaff with photographs by Julie Adams 1 A SELECTION OF LATIN INSCRIPTIONS AT WINCHESTER CATHEDRAL by Pat Wagstaff Pat Wagstaff was a Cathedral Guide at Winchester between 2002 and 2009. She and her husband moved to Norwich in September 2009, and she is currently a guide at Norwich Cathedral. Introduction The idea for this publication evolved from tours of Latin epitaphs in the Cathedral which I led for Cathedral Guides and for the general public. It is, of necessity only a short selection of epitaphs. I have chosen those which are representative of the people buried or commemorated in the Cathedral and I have also tried to include examples of typical abbreviations and expressions. The translations are my own except for those marked [GC] at the end. Those translations are by Guy Clarke who left for the Guides a file of beautifully handwritten translations. The order of the booklet follows that of a typical guided tour through the Cathedral, beginning at the west end, proceeding along the north side into the Retroquire and then down into the south transept, into the nave and finally into the south nave aisle. The numbers on the Cathedral plan below correspond to the numbers assigned to the epitaphs in the text. Inscriptions marked with an asterisk * are visible only when the chairs have been removed from the nave of the Cathedral. Two of the memorials marked ** are currently under a temporary extension to the nave dais. There are two appendices, one giving notes on common phrases or words used in epitaphs and the other giving information on the way Latin is used to give dates. -

Church and People in Interregnum Britain

Downloaded from the Humanities Digital Library http://www.humanities-digital-library.org Open Access books made available by the School of Advanced Study, University of London Press ***** Publication details: Church and People in Interregnum Britain Edited by Fiona McCall https://humanities-digital-library.org/index.php/hdl/catalog/book/ church-and-people-in-interregnum-britain DOI: 10.14296/2106.9781912702664 ***** This edition published in 2021 by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON PRESS SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU, United Kingdom ISBN 978-1-912702-66-4 (PDF edition) This work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses Church and people in interregnum Britain New Historical Perspectives is a book series for early career scholars within the UK and the Republic of Ireland. Books in the series are overseen by an expert editorial board to ensure the highest standards of peer-reviewed scholarship. Commissioning and editing is undertaken by the Royal Historical Society, and the series is published under the imprint of the Institute of Historical Research by the University of London Press. The series is supported by the Economic History Society and the Past and Present Society. Series co-editors: Heather Shore (Manchester Metropolitan University) and Elizabeth Hurren (University of Leicester) Founding co-editors: Simon Newman (University -

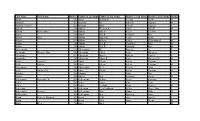

Last Name First Name Birth Yrfather's Last Name Father's

Last Name First Name Birth YrFather's Last Name Father's First Name Mother's Last Name Mother's First Name Gender Aaron 1907 Aaron Benjaman Shields Minnie M Aaslund 1893 Aaslund Ole Johnson Augusta M Aaslund (Twins) 1895 Aaslund Oluf Carlson Augusta F Abbeal 1906 Abbeal William A Conlee Nina E M Abbitz Bertha Dora 1896 Abbitz Albert Keller Caroline F Abbot 1905 Abbot Earl R Seldorff Rose F Abbott Zella 1891 Abbott James H Perry Lissie F Abbott 1896 Abbott Marion Forder Charolotta M M Abbott 1904 Abbott Earl R Van Horn Rose M Abbott 1906 Abbott Earl R Silsdorff Rose M Abercrombie 1899 Abercrombie W Rogers A F Abernathy Marjorie May 1907 Abernathy Elmer Scott Margaret F Abernathy 1892 Abernathy Wm A Roberts Laura J F Abernethy 1905 Abernethy Elmer R Scott Margaret M M Abikz Louisa E 1902 Abikz Albert Keller Caroline F Abilz Charles 1903 Abilz Albert Keller Caroline M Abircombie 1901 Abircombie W A Racher Allos F Abitz Arthur Carl 1899 Abitz Albert Keller Caroline M Abrams 1902 Abrams L E Baker May F Absher 1905 Absher Ben Spillman Zoida M Achermann Bernadine W 1904 Ackermann Arthur Krone Karolina F Acker 1903 Acker Louis Carr Lena F Acker 1907 Acker Leyland Ryan Beatrice M Ackerman 1904 Ackerman Cecil Addison Willis Bessie May F Ackermann Berwyn 1905 Ackermann Max Mann Dolly M Acklengton 1892 Achlengton A A Riacting Nattie F Acton Rebecca Elizabeth 1891 Acton T M Cox Josie E F Acton 1900 Acton Chas Payne Minnie M Adair Elles 1906 Adair Adel M Last Name First Name Birth YrFather's Last Name Father's First Name Mother's Last Name Mother's -

Friends Acquisitions 1964-2018

Acquired with the Aid of the Friends Manuscripts 1964: Letter from John Dury (1596-1660) to the Evangelical Assembly at Frankfurt-am- Main, 6 August 1633. The letter proposes a general assembly of the evangelical churches. 1966: Two letters from Thomas Arundel, Archbishop of Canterbury, to Nicholas of Lucca, 1413. Letter from Robert Hallum, Bishop of Salisbury concerning Nicholas of Lucca, n.d. 1966: Narrative by Leonardo Frescobaldi of a pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 1384. 1966: Survey of church goods in 33 parishes in the hundreds of Blofield and Walsham, Norfolk, 1549. 1966: Report of a debate in the House of Commons, 27 February 1593. From the Fairhurst Papers. 1967: Petition to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners by Miles Coverdale and others, 1565. From the Fairhurst Papers. 1967: Correspondence and papers of Christopher Wordsworth (1807-1885), Bishop of Lincoln. 1968: Letter from John Whitgift, Archbishop of Canterbury, to John Boys, 1599. 1968: Correspondence and papers of William Howley (1766-1848), Archbishop of Canterbury. 1969: Papers concerning the divorce of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon. 1970: Papers of Richard Bertie, Marian exile in Wesel, 1555-56. 1970: Notebook of the Nonjuror John Leake, 1700-35. Including testimony concerning the birth of the Old Pretender. 1971: Papers of Laurence Chaderton (1536?-1640), puritan divine. 1971: Heinrich Bullinger, History of the Reformation. Sixteenth century copy. 1971: Letter from John Davenant, Bishop of Salisbury, to a minister of his diocese [1640]. 1971: Letter from John Dury to Mr. Ball, Preacher of the Gospel, 1639. 1972: ‘The examination of Valentine Symmes and Arthur Tamlin, stationers, … the Xth of December 1589’. -

The Canons of Winchester in the Long Eighteenth Century

Proc. Hampshire Field. Club Archaeol. Soc. 63, 2008, 37-57 (Hampshire Studies 2008) A PRETTY EASY WAY OF DAWDLING AWAY ONE'S TIME: THE CANONS OF WINCHESTER IN THE LONG EIGHTEENTH CENTURY By GRAHAM HENDY ABSTRACT of that great diarist Parson Woodforde are borne out by his capitular contemporaries . We In the context of the 'long' eighteenth century shall examine them in the context of chapter (1660—1840) the prebendaries or canons residen and within the wider Church of England, noting tiary of Winchester Cathedral are investigated. Their their attitudes to residence and non-residence, families, and their geographical and educational and reflecting on their pastoral, theological backgrounds are examined, along with their literary and academic contribution to the age in which achievements. Career paths, patronage and financial they lived. rewards of their various livings are reviewed. Then This study will examine the 'Georgian' period follows an analysis of their work, and the worship from 1660-1840. The 'long eighteenth century' and care of the building in which they serve, particu is well established and accepted in ecclesiastical larly with reference to the question of 'residence' which historiography, beginning with the Restoration is determined by a detailed report on their attendance of Church and Monarchy, and ending with the at chapter meetings and at daily worship. Finally the Cathedrals Act of 1840. The church of the late prebendaries are seen within their social milieu. This seventeenth century and of the eighteenth paper may be set in the context of the current, more century was a slow moving structure, and was favourable, analysis of the Georgian church, which the obvious fruit of its medieval and Refor recognises there were plenty of good men who were mation past. -

A War of Religion

A War of Religion Dissenters, Anglicans, and the American Revolution James B. Bell PPL-UK_WR-Bell_FM.qxd 3/27/2008 1:52 PM Page i Studies in Modern History General Editor: J. C. D. Clark, Joyce and Elizabeth Hall Distinguished Professor of British History, University of Kansas Titles include: James B. Bell Mark Keay A WAR OF RELIGION WILLIAM WORDSWORTH’S Dissenters, Anglicans, and the GOLDEN AGE THEORIES DURING American Revolution THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION IN ENGLAND, 1750–1850 James B. Bell THE IMPERIAL ORIGINS OF THE Kim Lawes KING’S CHURCH IN EARLY AMERICA, PATERNALISM AND POLITICS 1607–1783 The Revival of Paternalism in Early Nineteenth-Century Britain Jonathan Clark and Howard Erskine-Hill (editors) Marisa Linton SAMUEL JOHNSON IN HISTORICAL THE POLITICS OF VIRTUE IN CONTEXT ENLIGHTENMENT FRANCE Eveline Cruickshanks and Howard Karin J. MacHardy Erskine-Hill WAR, RELIGION AND COURT THE ATTERBURY PLOT PATRONAGE IN HABSBURG Diana Donald and AUSTRIA Frank O’Gorman (editors) The Social and Cultural ORDERING THE WORLD IN THE Dimensions of Political Interaction, EIGHTEENTH CENTURY 1521–1622 Richard D. Floyd James Mackintosh RELIGIOUS DISSENT AND POLITICAL VINDICIÆ GALLICÆ MODERNIZATION Defence of the French Revolution: Church, Chapel and Party in A Critical Edition Nineteenth-Century England Robert J. Mayhew Richard R. Follett LANDSCAPE, LITERATURE AND EVANGELICALISM, PENAL THEORY ENGLISH RELIGIOUS CULTURE, AND THE POLITICS OF CRIMINAL 1660–1800 LAW REFORM IN ENGLAND, Samuel Johnson and Languages of 1808–30 Natural Description Andrew Godley Marjorie Morgan JEWISH IMMIGRANT NATIONAL IDENTITIES AND TRAVEL ENTREPRENEURSHIP IN NEW YORK IN VICTORIAN BRITAIN AND LONDON, 1880–1914 James Muldoon William Anthony Hay EMPIRE AND ORDER THE WHIG REVIVAL, 1808–1830 The Concept of Empire, 800–1800 PPL-UK_WR-Bell_FM.qxd 3/27/2008 1:52 PM Page ii W.