Images of Rule by David Howarth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archdiocesan Information About Diocesan Priests the Following Is the Most Recent List Abita Springs Marrero Rev

New Orleans CLARION HERALD 6 October 1, 2005 Archdiocesan information about diocesan priests The following is the most recent list Abita Springs Marrero Rev. Joe Palermo, Baton Rouge (Sept. 27) of archdiocesan priests who have Rev. Joseph Cazenavette, St. Edward the Msgr. Larry Hecker, Holy Family, Port Rev. Paul Passant, Destrehan reported to the Department of Clergy their Confessor, Metairie Allen, La. Rev. Wayne Paysse, St. Louis King of present locations: Rev. Beau Charbonnet, St. Anselm, Msgr. Ken Hedrick, St. Angela Merici, France, Baton Rouge Madisonville Metairie Rev. Denver Pentecost, Florida Rev. Harry Adams, St. Joachim, Marrero Msgr. Joseph Chotin, Mandeville Rev. Carroll Heffner, Our Lady of the Pines, Rev. Denzil Perera, Safe Rev. Edmund Akordor, Holy Family, Rev. John Cisewski, St. Hubert, Garyville Chatawa Rev. Nick Pericone, Most Blessed Sacra- Natchez, Miss. Rev. Victor Cohea, Oakvale, Miss. Rev. Luis Henao, St. Margaret Mary, ment, Baton Rouge Rev. Ken Allen, St. Joan of Arc, LaPlace Rev. Patrick Collum, St. Paul, Brandon, Slidell Rev. Anton Perkovic, St. Joseph Abbey Rev. G Amaldoss, St. Pius X, Crown Point Miss. Rev. John Hinton, Safe Rev. John Perino, Holy Family, Luling Rev. Jaime Apolinares, California Rev. Warren Cooper, Immaculate Concep- Msgr. Howard Hotard, Covington Rev. Dr. Tam Pham, St. Anthony, Baton Rev. John Arnone, Holy Name of Mary, tion, Marrero Archbishop Alfred Hughes, Our Lady of Rouge New Orleans Rev. Desmond Crotty, Metairie Mercy, Baton Rouge Rev. Tuan Pham, St. Peter, Reserve Rev. John Asare-Dankwah, Holy Family, Rev. Cal Cuccia, Our Lady of Divine Provi- Rev. Dominic Huyen, California Rev. Anton Ba Phan, Safe Natchez, Miss. -

A Brief History of Christ Church MEDIEVAL PERIOD

A Brief History of Christ Church MEDIEVAL PERIOD Christ Church was founded in 1546, and there had been a college here since 1525, but prior to the Dissolution of the monasteries, the site was occupied by a priory dedicated to the memory of St Frideswide, the patron saint of both university and city. St Frideswide, a noble Saxon lady, founded a nunnery for herself as head and for twelve more noble virgin ladies sometime towards the end of the seventh century. She was, however, pursued by Algar, prince of Leicester, for her hand in marriage. She refused his frequent approaches which became more and more desperate. Frideswide and her ladies, forewarned miraculously of yet another attempt by Algar, fled up river to hide. She stayed away some years, settling at Binsey, where she performed healing miracles. On returning to Oxford, Frideswide found that Algar was as persistent as ever, laying siege to the town in order to capture his bride. Frideswide called down blindness on Algar who eventually repented of his ways, and left Frideswide to her devotions. Frideswide died in about 737, and was canonised in 1480. Long before this, though, pilgrims came to her shrine in the priory church which was now populated by Augustinian canons. Nothing remains of Frideswide’s nunnery, and little - just a few stones - of the Saxon church but the cathedral and the buildings around the cloister are the oldest on the site. Her story is pictured in cartoon form by Burne-Jones in one of the windows in the cathedral. One of the gifts made to the priory was the meadow between Christ Church and the Thames and Cherwell rivers; Lady Montacute gave the land to maintain her chantry which lay in the Lady Chapel close to St Frideswide’s shrine. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT of INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION in Re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMEN

USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 1 of 354 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION ) Case No. 3:05-MD-527 RLM In re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE ) (MDL 1700) SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMENT ) PRACTICES LITIGATION ) ) ) THIS DOCUMENT RELATES TO: ) ) Carlene Craig, et. al. v. FedEx Case No. 3:05-cv-530 RLM ) Ground Package Systems, Inc., ) ) PROPOSED FINAL APPROVAL ORDER This matter came before the Court for hearing on March 11, 2019, to consider final approval of the proposed ERISA Class Action Settlement reached by and between Plaintiffs Leo Rittenhouse, Jeff Bramlage, Lawrence Liable, Kent Whistler, Mike Moore, Keith Berry, Matthew Cook, Heidi Law, Sylvia O’Brien, Neal Bergkamp, and Dominic Lupo1 (collectively, “the Named Plaintiffs”), on behalf of themselves and the Certified Class, and Defendant FedEx Ground Package System, Inc. (“FXG”) (collectively, “the Parties”), the terms of which Settlement are set forth in the Class Action Settlement Agreement (the “Settlement Agreement”) attached as Exhibit A to the Joint Declaration of Co-Lead Counsel in support of Preliminary Approval of the Kansas Class Action 1 Carlene Craig withdrew as a Named Plaintiff on November 29, 2006. See MDL Doc. No. 409. Named Plaintiffs Ronald Perry and Alan Pacheco are not movants for final approval and filed an objection [MDL Doc. Nos. 3251/3261]. USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 2 of 354 Settlement [MDL Doc. No. 3154-1]. Also before the Court is ERISA Plaintiffs’ Unopposed Motion for Attorney’s Fees and for Payment of Service Awards to the Named Plaintiffs, filed with the Court on October 19, 2018 [MDL Doc. -

Richard Hooker

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com 2,or. - Qºbe (5teat Qbutchmen 56tíč3 EDITED by VERNON STALEY RICHARD HOOKER ** - - - ---- -- ---- - -- ---- ---_ RICHARD HOOKER. Picture from National Portrait Gallery, by perm 13.5 to ºr 0. 'f Macmillan & Co. [Frontispiece. ICHARD as at HOOKER at By VERNON STALEY PROVOST OF THE CATHEDRAL CHURCH of ST. ANDREW, INVERNESS ... • * * * LONDON: MASTERS & CO., LTD. 1907 78, NEW BOND STREET, w. \\ \ \ EDITOR'S PREFACE It has been recently said by one accustomed to weigh his words, “I do not think it can be doubted that in the early years of Queen Elizabeth a large part, numerically the larger part, of the clergy and laity who made up the Church of England was really Catholic at heart, though the Reformers made up for deficiency of numbers by energy and force of conviction.” And again, “When Elizabeth came to the throne, the nation was divided between a majority of more or less lukewarm Catholics no longer to be called Roman, and a minority of ardent Protestants, who were rapidly gaining—though they had not quite gained—the upper hand. The Protestantism generally was of a type current in South West Germany and Switzerland, but the influence of Calvin was increasing every day.” Dr. Sanday here uses the term “Catholics,” in the * Dr. Sanday, Minutes of Evidence taken before The Royal Com †: on Ecclesiastical Discipline, 1906. Vol. III. p. 20, §§ 16350, V b 340844 vi EDITOR'S PREFACE sense of those who were attached to the old faith and worship minus certain exaggerations, but who disliked the Roman interference in England. -

Angliæ Notitia, Or, the Present State of England with Divers Remarks Upon

s/3/ AKGLIM N0TIT1A: jyhn or,the/w/ ENGLAND: With Divers REMARK S UPON The Ancient State thereof. By EDW. CHAMBERLATNE, Doctor of Laws. The Nineteenth Edition, with great Additions and Improvements. In Three PARTS. Sfart am quam naff us efi banc ornni. LONDON, Printed by T. Hodgkin, for R. Cbiftveil, M.Gillyfioretr, S. Sonith and B. Watford, M. Wotton, G. Sanbridgs, and B. Toots, 1700. Moft Excellent Majefty, william m. K I N G O F GreauBritain, Frame3 and Ireland’ Defender of the Truly Ancient, C.i- tholick, and Apoftolick Faith. This Nineteenth Impreffton of the (P RE¬ SENT STATE of ENG¬ LAND is Humbly Dedicated By Edw. Chamberlayne, Doftor of Laws. THE CONTENTS. A Defeription of England in general. Chap. X. Of its Name, Climate, Dimenfms, Di- Chap. II. Of the Bifhopricks of England. Chap. III. A Defcriftm of the feveral Counties tf England and Wales. Chap. IV. Of its Air, Soil, and Commodities. Chap. V. Of its Inhabitants, their Number, Language, and Character. Chap. VI. Of Religion. Chap. VII. Of Trade. GOVERNMENT. Chap. I. QF the Government of England in ge- Chap.II. Of the KJng of England, and therein of his Name, Title, Pcrfon, Office, Supremacy and Sove¬ reignty, Potter and Prerogative, Dominions, Strength, Patrimony, Arms and Ref fell. Chap. III. Of the SucceJJion to the Croton of England, and the King’s Minority, Incapacity and Abjence. Chap. IV. Of the prefent King of England ; and therein of his Birth, Name, Simame, and Genealogy, Arms, Title, Education, Marriage, Exploits, and Accef- fiyn to the Crown of England. -

Thank You for Your Generosity. Thursday, Oct. 31, Bishop Roger

IMMACULATE CONCEPTION THIRTY-SECOND SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME NOVEMBER 10, 2019 MARRERO, LOUISIANA VOLUME 49, NUMBER 19 Sunday, November 3, 2019 Weekly Collection Thursday, Oct. 31, Bishop Roger Morin passed away during a return flight from Envelopes……………....$4,704.00 Massachusetts. That must have been Loose……………..…….$1,712.00 Total Collection…...…...$6,416.00 some flight. Roger first came to New Orle- ans in the early 1970’s to work in the Sum- Thank you for your generosity. mer Witness Program sponsored by Arch- REFLECTIONS ON TODAYS READINGS bishop Hannan. He was a seminarian at Poor Sadducees! Unable to imagine a resurrection the time for Boston. He took a leave of ab- after one’s earthly life, they instead imagine conun- sence and requested to work for the Sum- drums that make the belief in resurrection look mer Witness Program full-time. He ended foolish. When someone remarries, who will be up working with Ben Johnson under the their spouse after the resurrection? Someone is direction of Arch. Hannan to form Social going to be left out. Jesus patiently explains to Services outreach of the Arch. N.O. Under them that this is not an issue in the coming age. their leadership New Orleans became na- The Sadducees have made the mistake of assum- tionally recognized leader in social ser- ing resurrected life if a continuation of earthly life. vices. Today we know this ministry as They have failed to imagine anything other than Catholic Charities. New Orleans is still life as they know it here on earth. With God, re- recognized nationally for its commitment member, all things are possible. -

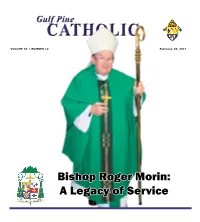

Bishop Roger Morin: a Legacy of Service 2 Most Reverend Roger P

Gulf Pine CATHOLIC VOLUME 34 / NUMBER 12 February 10, 2017 Bishop Roger Morin: A Legacy of Service 2 Most Reverend Roger P. Morin Third Bishop of Biloxi (2009 - 2016) Bishop Roger Paul Morin was Orleans. In 1973, he was appointed associate director of Bishop Morin received the Weiss Brotherhood Award installed as the third Bishop of Biloxi the Social Apostolate and in 1975 became the director, presented by the National Conference of Christians and on April 27, 2009, at the Cathedral of responsible for the operation of nine year-round social Jews for his service in the field of human relations. the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin service centers sponsored by the archdiocese. Bishop Bishop Morin was a member of the USCCB’s Mary by the late Archbishop Pietro Morin holds a master of science degree in urban studies Subcommittee on the Catholic Campaign for Human February 10, 2017 • Bishop Morin Sambi, Apostolic Nuncio to the from Tulane University and completed a program in Development 2005-2013, and served as Chairman 2008- United States, and Archbishop 1974 as a community economic developer. He was in 2010. During that time, he also served as a member of Thomas J. Rodi, Metropolitan Archbishop of Mobile. residence at Incarnate Word Parish beginning in 1981 the Committee on Domestic Justice and Human A native of Dracut, Mass., he was born on March 7, and served as pastor there from 1988 through April 2002. Development and the Committee for National 1941, the son of Germain J. and Lillian E. Morin. He has Bishop Morin is the Founding President of Second Collections. -

Twenty-Fourth Sunday of Ordinary Time September 13, 2020

Twenty-fourth Sunday of Ordinary Time September 13, 2020 Scripture Readings OUR ARCHDIOCESAN FAMILY PRAYER Loving and Faithful God, through the years Sirach 27:30-28:9 the people of our archdiocese have appreciated Romans 14:7-9 the prayers and love of Our Lady of Prompt Succor in times of war, disaster, epidemic and illness. Matthew 18:21-35 We come to you, Father, with Mary our Mother, and ask you to help us in the battle of today Music against violence, murder and racism. 9:30 am, 11:00 am, & 7:30 pm We implore you to give us your wisdom that we may build a community Gathering #562 Come Now, Almighty founded on the values of Jesus, which gives respect King to the life and dignity of all people. Bless parents Psalm Response “The Lord is kind and merciful, slow that they may form their children in faith. to anger, and rich in compassion.” Bless and protect our youth that they may be peacemakers of our time. Gifts Preparation #650 These Alone Are Enough Give consolation to those who have lost loved ones through violence. Hear our prayer and give us the perseverance Recessional #641 Love Divine, All Loves to be a voice for life and human dignity Excelling in our community. The texts of the Mass responses, as well as the Gloria We ask this through Christ our Lord. and Creed, can be found in the front cover of the Our Lady of Prompt Succor, hasten to help us. worship aids. Mother Henriette Delille, pray for us Sunday evening Benediction hymns can be found in that we may be a holy family. -

Restoration, Religion, and Revenge Heather Thornton Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2005 Restoration, religion, and revenge Heather Thornton Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Thornton, Heather, "Restoration, religion, and revenge" (2005). LSU Master's Theses. 558. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/558 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RESTORATION, RELIGION AND REVENGE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History By Heather D. Thornton B.A., Lousiana State University, 1999 M. Div., Golden Gate Baptist Theological Seminary, 2002 December 2005 In Memory of Laura Fay Thornton, 1937-2003, Who always believed in me ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank many people who both encouraged and supported me in this process. My advisor, Dr. Victor Stater, offered sound criticism and advice throughout the writing process. Dr. Christine Kooi and Dr. Maribel Dietz who served on my committee and offered critical outside readings. I owe thanks to my parents Kevin and Jorenda Thornton who listened without knowing what I was talking about as well as my grandparents Denzil and Jo Cantley for prayers and encouragement. -

Episcopal Tombs in Early Modern England

Jnl of Ecclesiastical History, Vol. 55, No. 4, October 2004. f 2004 Cambridge University Press 654 DOI: 10.1017/S0022046904001502 Printed in the United Kingdom Episcopal Tombs in Early Modern England by PETER SHERLOCK The Reformation simultaneously transformed the identity and role of bishops in the Church of England, and the function of monuments to the dead. This article considers the extent to which tombs of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century bishops represented a set of episcopal ideals distinct from those conveyed by the monuments of earlier bishops on the one hand and contemporary laity and clergy on the other. It argues that in death bishops were increasingly undifferentiated from other groups such as the gentry in the dress, posture, location and inscriptions of their monuments. As a result of the inherent tension between tradition and reform which surrounded both bishops and tombs, episcopal monuments were unsuccessful as a means of enhancing the status or preserving the memory and teachings of their subjects in the wake of the Reformation. etween 1400 and 1700, some 466 bishops held office in England and Wales, for anything from a few months to several decades.1 The B majority died peacefully in their beds, some fading into relative obscurity. Others, such as Richard Scrope, Thomas Cranmer and William Laud, were executed for treason or burned for heresy in one reign yet became revered as saints, heroes or martyrs in another. Throughout these three centuries bishops played key roles in the politics of both Church and PRO=Public Record Office; TNA=The National Archives I would like to thank Craig D’Alton, Felicity Heal, Clive Holmes, Ralph Houlbrooke, Judith Maltby, Keith Thomas and the anonymous reader for this JOURNAL for their comments on this article. -

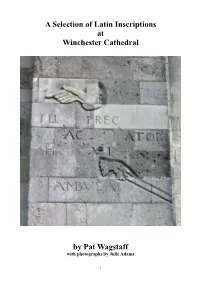

A SELECTION of LATIN INSCRIPTIONS at WINCHESTER CATHEDRAL by Pat Wagstaff

A Selection of Latin Inscriptions at Winchester Cathedral by Pat Wagstaff with photographs by Julie Adams 1 A SELECTION OF LATIN INSCRIPTIONS AT WINCHESTER CATHEDRAL by Pat Wagstaff Pat Wagstaff was a Cathedral Guide at Winchester between 2002 and 2009. She and her husband moved to Norwich in September 2009, and she is currently a guide at Norwich Cathedral. Introduction The idea for this publication evolved from tours of Latin epitaphs in the Cathedral which I led for Cathedral Guides and for the general public. It is, of necessity only a short selection of epitaphs. I have chosen those which are representative of the people buried or commemorated in the Cathedral and I have also tried to include examples of typical abbreviations and expressions. The translations are my own except for those marked [GC] at the end. Those translations are by Guy Clarke who left for the Guides a file of beautifully handwritten translations. The order of the booklet follows that of a typical guided tour through the Cathedral, beginning at the west end, proceeding along the north side into the Retroquire and then down into the south transept, into the nave and finally into the south nave aisle. The numbers on the Cathedral plan below correspond to the numbers assigned to the epitaphs in the text. Inscriptions marked with an asterisk * are visible only when the chairs have been removed from the nave of the Cathedral. Two of the memorials marked ** are currently under a temporary extension to the nave dais. There are two appendices, one giving notes on common phrases or words used in epitaphs and the other giving information on the way Latin is used to give dates. -

Church and People in Interregnum Britain

Downloaded from the Humanities Digital Library http://www.humanities-digital-library.org Open Access books made available by the School of Advanced Study, University of London Press ***** Publication details: Church and People in Interregnum Britain Edited by Fiona McCall https://humanities-digital-library.org/index.php/hdl/catalog/book/ church-and-people-in-interregnum-britain DOI: 10.14296/2106.9781912702664 ***** This edition published in 2021 by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON PRESS SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU, United Kingdom ISBN 978-1-912702-66-4 (PDF edition) This work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses Church and people in interregnum Britain New Historical Perspectives is a book series for early career scholars within the UK and the Republic of Ireland. Books in the series are overseen by an expert editorial board to ensure the highest standards of peer-reviewed scholarship. Commissioning and editing is undertaken by the Royal Historical Society, and the series is published under the imprint of the Institute of Historical Research by the University of London Press. The series is supported by the Economic History Society and the Past and Present Society. Series co-editors: Heather Shore (Manchester Metropolitan University) and Elizabeth Hurren (University of Leicester) Founding co-editors: Simon Newman (University