Moral Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women in Early Pythagoreanism

Women in Early Pythagoreanism Caterina Pellò Faculty of Classics University of Cambridge Clare Hall February 2018 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Alla nonna Ninni, che mi ha insegnato a leggere e scrivere Abstract Women in Early Pythagoreanism Caterina Pellò The sixth-century-BCE Pythagorean communities included both male and female members. This thesis focuses on the Pythagorean women and aims to explore what reasons lie behind the prominence of women in Pythagoreanism and what roles women played in early Pythagorean societies and thought. In the first chapter, I analyse the social conditions of women in Southern Italy, where the first Pythagorean communities were founded. In the second chapter, I compare Pythagorean societies with ancient Greek political clubs and religious sects. Compared to mainland Greece, South Italian women enjoyed higher legal and socio-political status. Similarly, religious groups included female initiates, assigning them authoritative roles. Consequently, the fact that the Pythagoreans founded their communities in Croton and further afield, and that in some respects these communities resembled ancient sects helps to explain why they opened their doors to the female gender to begin with. The third chapter discusses Pythagoras’ teachings to and about women. Pythagorean doctrines did not exclusively affect the followers’ way of thinking and public activities, but also their private way of living. Thus, they also regulated key aspects of the female everyday life, such as marriage and motherhood. I argue that the Pythagorean women entered the communities as wives, mothers and daughters. Nonetheless, some of them were able to gain authority over their fellow Pythagoreans and engage in intellectual activities, thus overcoming the female traditional domestic roles. -

4 the Problem of Women Philosophers in Ancient Greece

er.. - - 71 •. r 4 The. Problem of Women philosophised is remarkahly small. Furthermore. I shall draw attention to nutjor methodological diffrculliesRichard involved Hawley in the study of the literary sources for the lives of these women. A pattern will develop that informs these sources, a patlern of women philosophers as anomalies whose depal1ure fro'." recognised social behaviour requires special explanation. These expla Philosophers in Ancient nations oflcn resort to the forniliar conccplUal link bclwcen women and the �orld of the senses, the physical, rather than that of the rational, the Greece· mtellectual. I shall confine my discussion to between the sixth century BC Hawley and the first century AD, thus avoiding Hypatia. The sources for Hypatia Richard are ate and bound up with the complexities involved in the study of any ! _ Chmtian ltterature of the period. As such she deserves to be studied sepa rately. Nor shall I discuss the complex and already well-documented case of Oh! There I met those few congenial maids Aspasia. Instead, I shall turn my attention to 'forgotten' woinen.' . Whom love hath warm'd, in philosophic shades; There still Leontium, on her sage's breast, Found lore and love, was tutor' d and caress' d; VIEWS OF THE MALE PHILOSOPHERS And there the clasp of Pythia's gentle arms ·Repaid the zeal which deified her char!ns. It is possible lha1 lhc fir.s1 .school to have encouraged the study of philoso The Attic Master, in Aspasia's eyes, phy by womc was lhat of the Pythagoreans in the mid-sixth century BC. -

Physics: Its Birth in Greek Ionia

28TH NOVEMBER 2019 Physics: its Birth in Greek Ionia Professor Edith Hall If we are to imagine the birth of Greek natural science and philosophy in the Asiatic city of Miletus in the 6th century BCE, we need first to imagine one of the most dramatic changes in the physical appearance of the environment that the ancient Greeks, or any humans in history, have ever witnessed. Much of what we now call western Turkey, approximately the whole middle third, stretching inland from the modern coast for a minimum of thirty miles, had not yet been created. Miletus in the sixth century BCE was a famous harbour town still surrounded on three sides—west, north, and east—by seawater. But the dusty ruins of Miletus now stand near a small modern town of Balat, miles from the sea in any direction at all. The Milesian thinkers who began discussing the unseen causes of the world were watching that world change almost every day. In about 1,000 BCE, their harbour began to silt up, as the winding (‘meandering’) River Maeander disgorged itself into the sea far to the north-west, and the heavy particles of rock and soil, ‘alluvium’, sank to the bottom of the estuary and stayed there. Every year that passed, the alluvium extended the shore towards Miletus. By the Christian era, Miletus itself was landlocked. The process must have been about half completed when the first natural scientists were alive. They will have mourned the inexorable annexation of their beloved sea by the stones of the Asiatic continent. -

The Book of Dead Philosophers

Praise for Simon Critchley's THE BOOK OF DEAD PHILOSOPHERS "A provocative and engrossing invitation to think about the human condition and what philosophy can and can't do to illuminate it." —Financial Times "Concise, witty and oddly heartening." —New Statesman (A 2008 Book of the Year) "Full of wonderful absurdities.... Extremely enjoyable." —The Independent (London) "Simon Critchley is probably the sharpest and most lucid philosopher writing in English today." —Tom McCarthy, author of Remainder "Ingenious. Packed with great stories." —Time Out London "A tremendous addition to an all too sparse literature. Brilliant, entertaining, informative." —New Humanist (UK) "A fabulous concept. [Critchley writes] with dash, humour and an eye for scandalous detail." —The Vancouver Sun "[Critchley is] among the hippest of (living) British philosophers." —The Book Bench, newyorker.com "Surprisingly good fun. Worthy of the prose writings of Woody Allen. .. Not the least of the pleasures of this odd book, lighthearted and occasionally facetious as it is, is that in surveying a chronological history of philoso• phers it provides a sweep through the entire history of philosophy itself." —The Irish Times "Critchley has a lightness of touch, a nimbleness of thought, and a mocking graveyard humour that puts you in mind of Hamlet with a skull." —The Independent on Sunday (London) Simon Critchley "The Book of Dead Philosophers is something of a magic trick: on the surface an amusing and bemused series of blackout sketches of philosophers' often rather humble THE BOOK OF and/or brutal deaths, it actually is an utterly serious, DEAD PHILOSOPHERS deeply moving, cant-free attempt to return us to the gor- geousness of material existence, to our creatureliness, to our clownish bodies, to the only immortality available to us (immersion in the moment). -

Important Notes for Science Education in the Early Roman Empire

Important Notes for The Scientist in the Early Roman Empire Copyright © Richard Carrier 2016 Chapter 1 Introduction On the Christianity-helped-science thesis compare the best case in Hannam 2009 with rebuttals of all cases in Carrier 2010, Efron 2009 and Gruner 1975. In this book I use “Roman” to refer to all Greek or Latin speaking inhabitants of the Roman Empire (whether actual Roman citizens or not). On the nature and origins of the university system, which arose after the 11th century, see Ferruolo 1998, Pedersen 1997, De Ridder-Symons 1992, Hastings 1987, Bowen 1975, and Haskins 1923 (with one possible exception in the East, the rather unique Academy of Constantinople, founded in the 5th century, developed in the 9th, and disbanded in the 14th: see Markopoulos 2008, Constantelos 1998 and, though perhaps less reliably, Kyriakis 1971). For a broad, although fairly unsophisticated introductory survey of the development of education from Greece, through Rome, into the Middle Ages and then the modern era, see Dobson 1932. For a broader multicultural survey of ancient education, see Bowen 1972. On science content of medieval universities see Rossi 2001: 192-202. It should also be noted that medieval students did not enjoy the same intellectual liberty that ancient students did (largely due to attitudes detailed here in chapter seven). See Freeman 2002, esp. where supported by Carrier 2010: 419 n. 56. On early American schools see Reese 2005. Quote from McGrayne 2011: 63. See also D. Lee 1973: 70-71 and Green 1990: 470-73 and 855 (notes 38 and 39). On the craze for mathematics in the Renaissance see Nahin 1998: 8-47. -

Artemis and Virginity in Ancient Greece

SAPIENZA UNIVERSITÀ DI ROMA FACOLTÀ DI LETTERE E FILOSOFIA DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN FILOLOGIA E STORIA DEL MONDO ANTICO XXVI CICLO ARTEMIS AND VIRGINITY IN ANCIENT GREECE TUTOR COTUTOR PROF. PIETRO VANNICELLI PROF. FRANCESCO GUIZZI 2 Dedication: To S & J with love and gratitude. Acknowledgements: I first and foremost wish to thank my tutor/advisor Professor Pietro Vannicelli and Co- Tutor Professor Francesco Guizzi for agreeing to serve in these capacities, for their invaluable advice and comments, and for their kind support and encouragement. I also wish to thank the following individuals who have lent intellectual and emotional support as well as provided invaluable comments on aspects of the thesis or offered advice and spirited discussion: Professor Maria Giovanna Biga, La Sapienza, and Professor Gilda Bartoloni, La Sapienza, for their invaluable support at crucial moments in my doctoral studies. Professor Emerita Larissa Bonfante, New York University, who proof-read my thesis as well as offered sound advice and thought-provoking and stimulating discussions. Dr. Massimo Blasi, La Sapienza, who proof-read my thesis and offered advice as well as practical support and encouragement throughout my doctoral studies. Dr. Yang Wang, Princeton University, who proof-read my thesis and offered many helpful comments and practical support. Dr. Natalia Manzano Davidovich, La Sapienza, who has offered intellectual, emotional, and practical support this past year. Our e-mail conversations about various topics related to our respective theses have -

The Complete Pythagoras

THE COMPLETE PYTHAGORAS INDEX INTRODUCTION VOLUME ONE Biographies Iamblichus i) Importance of the Subject ii) Youth, Education, Travels iii) Journey to Egypt iv) Studies in Egypt and Babylonia v) Travels in Greece, Settlement at Crotona vi) Pythagorean Community vii) Italian Political Achievements viii) Intuition, Reverence, Temperance, Studiousness ix) Community and Chastity x) Advice to Youths xi) Advice to Women xii) Why he calls himself a Pythagorean xiii) He shared Orpheus’s Control over Animals xiv) Pythagoras ’s preexistence xv) He Cured by Medicine and Music xvi) Pythagorean Aestheticism xvii) Tests of Initiation xviii) Organization of the Pythagorean School xix) Abaris the Scythian xx) Psychological Requirements xxi) Daily Program xxii) Friendship xxiii) Use of parables in Instruction xxiv) Dietary Suggestions xxv) Music and poetry xxvi) Theoretical Music xxvii) Mutual political Assistance xxviii) Divinity of Pythagoras xxix) Sciences and Maxims xxx) Justice and politics xxxi) Temperance and Self-control xxxii) Fortitude xxxiii) Universal Friendship xxxiv) Nonmercenary Secrecy xxxv) Attack on Pythagoreanism xxxvi) The Pythagorean Succession Porphry Photius Diogenes Laertius i) Early Life ii) Studies iii) Initiations iv) Transmigration v) Works vi) General Views on Life vii) Ages of Life viii) Social Customs ix) Distinguished Appearance x) Women Deified by Marriage xi) Scientific culture xii) Diet and Sacrifices xiii) Measures and Weights xiv) Hesperus Identified with Lucifer xv) Students and Reputations xvi) Friendship Founded -

Diogenes Laertius Lives of the Philosophers: Thales, Translated by C.D

Diogenes Laertius Lives of the Philosophers: Thales, translated by C.D. Yonge Peithô's Web Lives index BOOK I. INTRODUCTION. I. SOME say that the study of philosophy originated with the barbarians. In that among the Persians there existed the Magi,1 and among the Babylonians or Assyrians the Chaldaei,2 among the Indians the Gymnosophistae,3 and among the Celts and Gauls men who were called Druids4 and Semnothei, as Aristotle relates in his book on Magic, and Sotion in the twenty-third book of his Succession of Philosophers. Besides those men there were the Phoenician Ochus, the Thracian Zamolxis,5 and the Libyan Atlas. For the Egyptians say that Vulcan was the son of Nilus*, and that he was the author of philosophy, in which those who were especially eminent were called his priests and prophets. II. From his age to that of Alexander, king of the Macedonians, were forty-eight thousand eight hundred and sixty-three years, and during this time there were three hundred and seventy-three eclipses of the sun, and eight hundred and thirty-two eclipses of the moon. Again, from the time of the Magi, the first of whom was Zoroaster the Persian, to that of the fall of Troy, Hermodorus the Platonic philosopher, in his treatise on Mathematics, calculates that fifteen thousand years elapsed. But Xanthus the Lydian says that the passage of the Hellespont by Xerxes took place six thousand years after the time of Zoroaster,6 and that after him there was a regular succession of Magi under the names of Ostanes and Astrampsychos and Gobryas and Pazatas, until the destruction of the Persian empire by Alexander. -

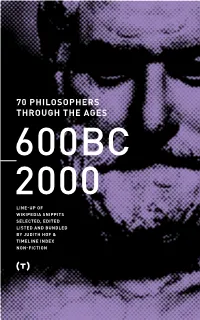

70 Philosophers Through the Ages 600Bc 2000 Line-Up of Wikipedia Snippits Selected, Edited Listed and Bundled by Judith Hof & Timeline Index Non-Fiction

70 PHILOSOPHERS THROUGH THE AGES 600BC 2000 LINE-UP OF WIKIPEDIA SNIPPITS SELECTED, EDITED LISTED AND BUNDLED BY JUDITH HOF & TIMELINE INDEX NON-FICTION 70 PHILOSOPHERS THROUGH THE AGES 70 PHILOSOPHERS THROUGH THE AGES 600BC - 2000 1 70 PHILOSOPHERS THROUGH THE AGES 70 Philosophers through the ages 600BC to 2000 Line-up from Wikipedia selected, edited, listed and bundled by Judith Hof & Timeline Index Publication and Design by Timeline Index, timelineindex.com Copyright © 2021 Timeline Index The content of this publication is released under CC BY-SA License: creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ ISBN: 9781477470008 Thank you Wikipedia. All profits will be donated to Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. TIMELINE INDEX non-fiction 2 70 PHILOSOPHERS THROUGH THE AGES Intro ‘70 Philosophers through the ages’ is meant as an introduction and, like our website, contains a chronological line-up of Wikipedia snippits. This hard copy may be usefull as a quick and easy reference to hold, keep, give or carry around and pick up where and whenever you feel like. Learn more on our website: timelineindex.com Philosophers longlist: timelineindex.com/philosophers Philosophers poster, free download to print, A3 full color: timelineindex.com/posters The selection of philosophers in this book is inevitably subjectieve and incomplete. We welcome your suggetions for improvement at: [email protected] Timeline Index is an ongoing project. We aim to provide a useful structure to help put information into context. 3 70 PHILOSOPHERS THROUGH THE AGES Contents Intro 3 Timeline index 5 Philosophers through the ages 8 Most well known philosophical movements 9 70 Philosophers from 600BC to 2000 11 A to Z index 176 Website 178 Poster 179 4 70 PHILOSOPHERS THROUGH THE AGES Timeline index Thales of Miletus Zeno of Elea Theophrastus c. -

The Presocratics an Overview

The PreSocratics An Overview PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 07 Mar 2011 08:07:22 UTC Contents Articles Introduction 1 Pre-Socratic philosophy 1 Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks 4 Classical element 9 Ionian School (philosophy) 15 Paired opposites 18 Material monism 21 Diogenes Laërtius 21 Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers 23 The Milesians 27 Milesian school 27 Thales 29 Anaximander 40 Anaximenes of Miletus 51 Pythagoreanism 53 Pythagoreanism 53 Pythagoras 59 Philolaus 70 Alcmaeon of Croton 72 Archytas 75 Ephesian School 78 Heraclitus 78 Eleatic School 89 Eleatics 89 Xenophanes 90 Parmenides 93 Zeno of Elea 100 Zeno's paradoxes 102 Melissus 109 Pluralists 110 Pluralist school 110 Empedocles 111 Anaxagoras 118 Atomists 122 Atomism 122 Leucippus 132 Democritus 134 The Sophists 144 Sophism 144 Protagoras 148 Gorgias 150 Hippias 155 Prodicus 156 The Seven Sages 160 Seven Sages of Greece 160 Solon 162 Chilon of Sparta 176 Bias of Priene 178 Cleobulus 180 Pittacus of Mytilene 181 Periander 182 Others 184 Diogenes of Apollonia 184 Aristeas 185 Pherecydes of Syros 187 Anacharsis 191 References Article Sources and Contributors 194 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 199 Article Licenses License 201 1 Introduction Pre-Socratic philosophy Pre-Socratic philosophy is Greek philosophy before Socrates. In Classical antiquity, the Presocratic philosophers were called physiologoi (in English, physical or natural philosophers).[1] Diogenes Laërtius divides the physiologoi into two groups, Ionian and Italiote, led by Anaximander and Pythagoras, respectively.[2] Hermann Diels popularized the term pre-socratic in Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker (The Fragments of the Pre-Socratics) in 1903. -

The Pythagorean Symbolism in Plato's Philebus

Athens Journal of History - Volume 2, Issue 2 – Pages 83-96 The Pythagorean Symbolism in Plato’s Philebus By Kenneth R. Moore The Philebus contains what may be called a Pythagorean semiotics. That is, the dialogue has a number of embedded references and allusions to central aspects and ideas of Pythagoreanism. These act as signposts to the informed reader/auditor which illuminate certain topics of discussion in the dialogue and furnish a rich subtext which, when properly decoded, imparts a greater degree of sophistication and meaning to the text as a whole. One level of this may be observed in the Pythagorean allusions by themselves, of which there are many. A deeper level of Pythagorean semiotics arguably occurs in the very fabric of the dialogue itself. It has been argued that the Platonic dialogues have been deliberately structured according to a Pythagorean division of the musical canon, with certain themes corresponding to the consonance or dissonance of a given "note" on the scale. This, along with the relevant symbolism present, will be examined in greater detail. The aim of Plato’s Philebus is to determine the Good. It is replete with Pythagorean symbolism occurring at multiple levels. Kennedy has asserted that Plato used stichometric (word-counting) techniques to structure his dialogues corresponding to a Pythagorean, 12-note system as well as an Orphic, 7-note scale. Certain "notes" in the dialogue are therefore "more consonant" or "more dissonant", revealing a subtext of authorial intent.1 Kennedy has provided me with a schema of the Philebus according to this theory. I shall examine major instances of Pythagorean symbolism at the textual level here and attempt to address several key "notes" within Philebus in order to test Kennedy’s model. -

Early Greek Poets' Lives : the Shaping of the Tradition / by Maarit Kivilo

Early Greek Poets’ Lives Mnemosyne Supplements Monographs on Greek and Roman Language and Literature Editorial Board G.J. Boter A. Chaniotis K.M. Coleman I.J.F. de Jong T. Reinhardt VOLUME 322 Early Greek Poets’ Lives The Shaping of the Tradition By Maarit Kivilo LEIDEN • BOSTON 2010 This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the prevailing CC-BY-NC License at the time of publication, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched (KU). KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality content Open Access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kivilo, Maarit. Early Greek poets' lives : the shaping of the tradition / by Maarit Kivilo. p. cm. – (Mnemosyne supplements : monographs on Greek and Roman language and literature ; 322) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-90-04-18615-6 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Poets, Greek–Biography–History and criticism. 2. Greek prose literature–History and criticism. 3. Greece–Biography–History and criticism. 4. Classical biography–History and criticism. 5. Hesiod. 6. Stesichorus. 7. Archilochus. 8. Hipponax, fl. 540-537 B.C. 9. Terpander. 10. Sappho. I. Title. II. Series. PA3043.K58 2010 881'.0109–dc22 [B] 2010017664 ISSN 0169-8958 ISBN 978 9004 18615 6 Copyright 2010 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands.