Star Trek's Native Americans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of English and American Studies Another

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature & Teaching English Language and Literature for Secondary Schools Bc. Ondřej Harnušek Another Frontier: The Religion of Star Trek Master‘s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Jeffrey Alan Smith, M.A., Ph. D. 2015 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author‘s signature Acknowledgements There are many people, who would deserve my thanks for this work being completed, but I am bound to omit someone unintentionally, for which I deeply apologise in advance. My thanks naturally goes to my family, with whom I used to watch Star Trek every day, for their eternal support and understanding; to my friends, namely and especially to Vítězslav Mareš for proofreading and immense help with the historical background, Miroslav Pilař for proofreading, Viktor Dvořák for suggestions, all the classmates and friends for support and/or suggestions, especially Lenka Pokorná, Kristina Alešová, Petra Grünwaldová, Melanie King, Tereza Pavlíková and Blanka Šustrová for enthusiasm and cheering. I want to thank to all the creators of ―Memory Alpha‖, a wiki-based web-page, which contains truly encyclopaedic information about Star Trek and from which I drew almost all the quantifiable data like numbers of the episodes and their air dates. I also want to thank to Christina M. Luckings for her page of ST transcripts, which was a great help. A huge, sincere thank you goes to Jeff A. Smith, my supervisor, and an endless source of useful materials, suggestions and ideas, which shaped this thesis, and were the primary cause that it was written at all. -

Star Trek" Mary Jo Deegan University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UNL | Libraries University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 1986 Sexism in Space: The rF eudian Formula in "Star Trek" Mary Jo Deegan University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Deegan, Mary Jo, "Sexism in Space: The rF eudian Formula in "Star Trek"" (1986). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 368. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/368 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THIS FILE CONTAINS THE FOLLOWING MATERIALS: Deegan, Mary Jo. 1986. “Sexism in Space: The Freudian Formula in ‘Star Trek.’” Pp. 209-224 in Eros in the Mind’s Eye: Sexuality and the Fantastic in Art and Film, edited by Donald Palumbo. (Contributions to the Study of Science Fiction and Fantasy, No. 21). New York: Greenwood Press. 17 Sexism in Space: The Freudian Formula in IIStar Trek" MARY JO DEEGAN Space, the final frontier. These are the voyages of the starship Enterprise, its five year mission to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations, to boldly go where no man has gone before. These words, spoken at the beginning of each televised "Star Trek" episode, set the stage for the fan tastic future. -

December 31, 2017 - January 6, 2018

DECEMBER 31, 2017 - JANUARY 6, 2018 staradvertiser.com WEEKEND WAGERS Humor fl ies high as the crew of Flight 1610 transports dreamers and gamblers alike on a weekly round-trip fl ight from the City of Angels to the City of Sin. Join Captain Dave (Dylan McDermott), head fl ight attendant Ronnie (Kim Matula) and fl ight attendant Bernard (Nathan Lee Graham) as they travel from L.A. to Vegas. Premiering Tuesday, Jan. 2, on Fox. Join host, Lyla Berg, as she sits down with guests Meet the NEW SHOW WEDNESDAY! who share their work on moving our community forward. people SPECIAL GUESTS INCLUDE: and places Mike Carr, President & CEO, USS Missouri Memorial Association that make Steve Levins, Executive Director, Office of Consumer Protection, DCCA 1st & 3rd Wednesday Dr. Lynn Babington, President, Chaminade University Hawai‘i olelo.org of the Month, 6:30pm Dr. Raymond Jardine, Chairman & CEO, Native Hawaiian Veterans Channel 53 special. Brandon Dela Cruz, President, Filipino Chamber of Commerce of Hawaii ON THE COVER | L.A. TO VEGAS High-flying hilarity Winners abound in confident, brash pilot with a soft spot for his (“Daddy’s Home,” 2015) and producer Adam passengers’ well-being. His co-pilot, Alan (Amir McKay (“Step Brothers,” 2008). The pair works ‘L.A. to Vegas’ Talai, “The Pursuit of Happyness,” 2006), does with the company’s head, the fictional Gary his best to appease Dave’s ego. Other no- Sanchez, a Paraguayan investor whose gifts By Kat Mulligan table crew members include flight attendant to the globe most notably include comedic TV Media Bernard (Nathan Lee Graham, “Zoolander,” video website “Funny or Die.” While this isn’t 2001) and head flight attendant Ronnie the first foray into television for the produc- hina’s Great Wall, Rome’s Coliseum, (Matula), both of whom juggle the needs and tion company, known also for “Drunk History” London’s Big Ben and India’s Taj Mahal demands of passengers all while trying to navi- and “Commander Chet,” the partnership with C— beautiful locations, but so far away, gate the destination of their own lives. -

'Star Trek': Humanism of the Future

'Star Trek': Humanism of the Future Note: Permission to publish photographs with this article was denied by Paramount Pictures, which deemed association with FREE INQUIRY "too controversial." —EDS. Kenneth Marsalek or the past twenty-five years, the science-fiction humanism, "Star Trek" does not consistently present a television series "Star Trek" has captivated millions humanistic viewpoint, but rather, reflects the views of many Fof fans with its hopeful view of humanity's future. Its writers, directors, actors, and producers. "Star Trek" has also positive vision stems from the philosophy of its creator, the dabbled in paranormal phenomena, pseudoscience, and late Gene Roddenberry, who presented a humanist message mysticism, which humanists may find counter-productive. I in the context of a fictional future. will focus on "Star Trek" 's humanistic aspects by reviewing "Star Trek" has enjoyed several incarnations. The original how religion is addressed in various episodes. series ran for three seasons beginning in 1966. It has been translated into forty-seven languages and still airs over two Religious Totalitarianism hundred times a day across the United States. It depicted the voyages of the starship U. S. S. Enterprise, with Captain IA nce each season, Captain Kirk's Enterprise encountered James T. Kirk; Mr. Spock, the half-Vulcan, half-human kl a society controlled by a super-computer. Although this Science Officer; and Dr. Leonard ("Bones') McCoy. An theme may be described as man vs. machine, it is more animated series aired for one year in 1973. Star Trek—The accurately viewed as man vs. religious totalitarianism. In each Motion Picture, the first of six full-length films, was released case, the computer is regarded as a "creator god" that satisfies in 1979. -

Risk Criticism: Precautionary Reading in an Age of Environmental

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE Revised Pages RISK CRITICISM Revised Pages Revised Pages Risk Criticism PRECAUTIONARY READING IN AN AGE OF ENVIRONMENTAL UNCERTAINTY Molly Wallace UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS Ann Arbor Revised Pages Copyright © 2016 by Molly Wallace All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2019 2018 2017 2016 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Wallace, Molly, author. Title: Risk criticism : precautionary reading in an age of environmental uncertainty / Molly Wallace. Description: Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2015038637 | ISBN 9780472073023 (hardback) | ISBN 9780472053025 (paperback) | ISBN 9780472121694 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Ecocriticism. | Criticism. | Risk in literature. | Environmental risk assessment. | Risk-taking (Psychology) Classification: LCC PN98.E36 W35 2016 | DDC 809/.93355— dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015038637 Revised Pages For my family Revised Pages Revised Pages Acknowledgments This book has been a number of years in the writing, and I am deeply grate- ful for the support and encouragement that I have received along the way. -

''Star Trek: the Original Series'': Season 3

''Star Trek: The Original Series'': Season 3 PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Thu, 13 Mar 2014 18:19:48 UTC Contents Articles Season Overview 1 Star Trek: The Original Series (season 3) 1 1968–69 Episodes 5 Spock's Brain 5 The Enterprise Incident 8 The Paradise Syndrome 12 And the Children Shall Lead 16 Is There in Truth No Beauty? 19 Spectre of the Gun 22 Day of the Dove 25 For the World Is Hollow and I Have Touched the Sky 28 The Tholian Web 32 Plato's Stepchildren 35 Wink of an Eye 38 The Empath 41 Elaan of Troyius 44 Whom Gods Destroy 47 Let That Be Your Last Battlefield 50 The Mark of Gideon 53 That Which Survives 56 The Lights of Zetar 58 Requiem for Methuselah 61 The Way to Eden 64 The Cloud Minders 68 The Savage Curtain 71 All Our Yesterdays 74 Turnabout Intruder 77 References Article Sources and Contributors 81 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 83 Article Licenses License 84 1 Season Overview Star Trek: The Original Series (season 3) Star Trek: The Original Series (season 3) Country of origin United States No. of episodes 24 Broadcast Original channel NBC Original run September 20, 1968 – June 3, 1969 Home video release DVD release Region 1 December 14, 2004 (Original) November 18, 2008 (Remastered) Region 2 December 6, 2004 (Original) April 27, 2009 (Remastered) Blu-ray Disc release Region A December 15, 2009 Region B March 22, 2010 Season chronology ← Previous Season 2 Next → — List of Star Trek: The Original Series episodes The third and final season of the original Star Trek aired Fridays at 10:00-11:00 pm (EST) on NBC from September 20, 1968 to March 14, 1969. -

Star Trek Kraith Creator's Manual Vol 1.Pdf

kRAlTb CR6ATOR!s CDANUAL vol.i (^ kRAlTh CR6ATORS 0^ CDANUAL vol. February 16, 1973 The Kraith Creator's Manual is available from the editors for $1.50, Fourth class postage is included in the purchase price. First class postage rates available on request. EDITORS: Carol Lynn 11524 Nashville in£>gx Detroit, Michigan 48205 Unless otherwise indicated the author is Jacqueline Debbie Goldstein 17511 Ohio Index i Detroit, Michigan Author's Foreward • 2 48221 Editor's Foreward 3 Carol Lynn Open Letter I 4 Part I: Character Developement jp\ ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: The Kirk/Spock Relationship -- 5 The Spock/T'Aniyeh Relationship 7 Typing: The Ssarsun Biography 9 Carol Lynn Part II: Background: Theoretical Debbie Goldstein In Defense of T'Yuzeti 14 ->tppgtrsfomh: The Vulcan Realms 26 Carol Lynn A Trisomic Model for Kataytikhe Genetics 28 Debbie Goldstein John Benson Titles: Beads and Rattles ----- 32 John Benson Vulcanur Seme mica 34 Cover: Part III: Background: Story Detail Robbie Brown The Culling Flame 50 Interior Art: The Joys of Vulcan 53 Janice, Page 45 Humor 55 Elizabeth Dailey Celebration 59 pgs. 52,54,55,59 Part IV: Story Outlines The Linger Death 54 The Lesson ^5 Part V.: Kraith Exchange The Letter File 53 Kraith Creators Roster :— 75 Reccomended Reading 77 Fondly dedicated to the IBM typewriter repairman who never did come to fix the n, t, and h 1 keys that don't type until they have been used several hundred times, the a key that sticks, f^ and the ribbon holder that doesn't. (S\ AUTHORS f ORGUIORD ($t\ MAY YOU LIVE LONG AND PROSPER: You will notice that most of the wordage in. -

Ethical Engineering for International

Marion Hersh Editor Ethical Engineering for International Development and Environmental Sustainability Ethical Engineering for International Development and Environmental Sustainability ThiS is a FM Blank Page Marion Hersh Editor Ethical Engineering for International Development and Environmental Sustainability Editor Marion Hersh School of Engineering University of Glasgow Glasgow , Scotland ISBN 978-1-4471-6617-7 ISBN 978-1-4471-6618-4 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-4471-6618-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2015934010 Springer London Heidelberg New York Dordrecht © Springer-Verlag London 2015 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

Intel International Science and Engineering Fair 2016 Program May 8 – 13, 2016 Phoenix, Arizona Intel International Science and Engineering Fair

THINK BEYOND Intel International Science and Engineering Fair 2016 Program May 8 – 13, 2016 Phoenix, Arizona Intel International Science and Engineering Fair About the Intel ISEF The Intel International Science and Engineering Fair (Intel ISEF), a program of Society for Science & the Public, is the world’s largest international pre-college science competition. The Intel ISEF is the premier science competition in the world and provides a forum for more than 1,750 high school students from more than 75 countries, regions and territories to showcase their independent research annually. Each year, millions of students worldwide compete in local science fairs; winners go on to participate in Intel ISEF-affiliated regional, state and national fairs to earn the opportunity to attend the Intel ISEF. Uniting these top young scientific minds, the Intel ISEF provides the opportunity to finalists to display their talent on an international stage, while enabling them to submit their work for judging by doctoral-level scientists. The Intel ISEF provides awards of nearly $4 million in prizes and scholarships annually. Intel International Science and Engineering Fair 2016 Intel International Science and Engineering Fair 2016 Greetings ..........................................................................................................2 Title Sponsor ..................................................................................................6 Gordon E. Moore Award ..........................................................................7 About -

Paved with the Best Intentions? Utopian Spaces in Star Trek, the Original Series (NBC, 1966-1969)

TV/Series 2 | 2012 Les séries télévisées dans le monde : Échanges, déplacements et transpositions ... Paved with the Best Intentions? Utopian Spaces in Star Trek, the Original Series (NBC, 1966-1969) Donna Spalding Andréolle Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/1376 DOI: 10.4000/tvseries.1376 ISSN: 2266-0909 Publisher GRIC - Groupe de recherche Identités et Cultures Electronic reference Donna Spalding Andréolle, « ... Paved with the Best Intentions? Utopian Spaces in Star Trek, the Original Series (NBC, 1966-1969) », TV/Series [Online], 2 | 2012, Online since 01 November 2012, connection on 20 April 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/1376 ; DOI : 10.4000/tvseries.1376 TV/Series est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. ... Paved with the Best Intentions? Utopian Spaces in Star Trek, the Original Series (NBC, 1966-1969) Donna SPALDING ANDRÉOLLE This paper is an examination of the ways in which the science fiction series Star Trek of the 1960s sheds light on a crucial moment in American history, the social context of which includes political turmoil and the questioning of mainstream values. The very structure of the episodes, often introduced by the captain’s log giving a stardate and a summary of the current situation of the starship Enterprise’s mission-in-progress, points to the exploratory traditions of the American nation built over an almost 300-year period of westward expansion. It is possible, then, to draw a parallel between the Enterprise’s journeys through the universe in search of “strange new planets and civilizations” (dixit Kirk’s voice in the credit scene) and the American quest for new lands needed to perpetuate the utopian project of democratic society first set into motion by the Puritans of New England in the 17th century. -

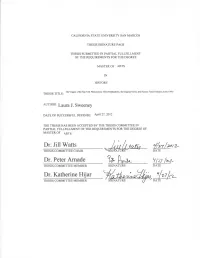

?R A,"T 2Lzar. THESIS COMMITTEE MEMBER SIGNATURE DATE Dr

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY SAN MARCOS THESIS SIGNATTIRE PAGE THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULLFILLMENT OT THE REQUIRXMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTEROF ARTS IN HISTORY The Origins ofthe Sta Trck Phenomaoa: Gme Roddaber4y, tie Origiml Ssieg and Science Fiction Sandom in the 1960s THESIS TITLE: AUTHOR; LaUra J. Sweeney DATE OF SUCCESSFUL DEFENSE: Apri127,2012 THE THESIS HAS BEEN ACCEPTED BY THE THESIS COMMITTEE IN PARTIAL FULLFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FORTHE DEGREE OF MASTEROF ARTS Dr. Jill Vflatts y'/"2/-,2 THESIS COMMITTEE CHAIR oArp Dr. Peter Arnade ?r A,"t 2lzAr. THESIS COMMITTEE MEMBER SIGNATURE DATE Dr. Katherine Hrjar rfzt l,- I THESIS COMMITTEE MEMBER DATE The Origins of the Star Trek Phenomenon: Gene Roddenberry, the Original Series, and Science Fiction Fandom in the 1960s Laura J. Sweeney Department of History California State University San Marcos © 2012 Dedication Mom, you are the only one that has been there for me through thick and thin consistently in my life. Without you, I would not have been able to attend graduate school and write this thesis. Thank you for all your support. I love you always. iii Acknowledgements There are so many wonderful people to thank for making this thesis possible. When I was researching graduate schools, I found California State University San Marcos History Department fascinating and I was overjoyed to be accepted. Yet, I had no idea what it would truly be like and still felt apprehensive on taking a chance. Many chances I took in life did not turn out so well, but this time I was incredibly blessed with good fortune. -

"Star Trek" and "Doctor Who"

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1987 A Critical Examination of the Mythological and Symbolic Elements of Two Modern Science Fiction Series: "Star Trek" and "Doctor Who". Gwendolyn Marie Olivier Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Olivier, Gwendolyn Marie, "A Critical Examination of the Mythological and Symbolic Elements of Two Modern Science Fiction Series: "Star Trek" and "Doctor Who"." (1987). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4373. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4373 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. For example: ® Manuscript pages may have indistinct print. In such cases, the best available copy has been filmed. • Manuscripts may not always be complete. In such cases, a note will indicate that it is not possible to obtain missing pages. • Copyrighted material may have been removed from the manuscript. In such cases, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps.