8612356.Pdf (5.81

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Young Boy in a Plumed Cap Black Chalk, with Traces of Red Chalk, and Framing Lines in Brown Ink

Jacob Adriaensz. BACKER (Harlingen 1608 - Amsterdam 1651) A Young Boy in a Plumed Cap Black chalk, with traces of red chalk, and framing lines in brown ink. Signed Backer. at the lower right. 168 x 182 mm. (6 5/8 x 7 1/8 in.) This charming drawing is a preparatory study for the pointing child at the extreme left of Jacob Backer’s Family Portrait with Christ Blessing the Children, a painting datable to c.1633-1634. This large canvas was unknown before its first appearance at auction in London in 1974, and is today in a private collection. The present sheet is drawn with a vivacity and a freedom in the application of the chalk that is stylistically indebted to Rembrandt’s chalk drawings of the same period, namely the early 1630s. Drawings executed in black chalk alone are rare in Backer’s oeuvre, but this drawing may be compared in particular to a signed and dated Self-Portrait in black chalk by Backer of 1638, in the Albertina in Vienna. A black chalk study of A Man in a Turban, in the Boijmans-van Beuningen Museum in Rotterdam, may also be likened to the present sheet. Provenance: Probably by descent to the artists’s brother, Tjerk Adriaensz. Backer, Amsterdam Iohan Quirijn van Regteren Altena, Amsterdam (his posthumous sale stamp [Lugt 4617] stamped on the backing sheet) Thence by descent. Literature: Werner Sumowski, Drawings of the Rembrandt School, Vol.I, New York, 1979, pp.20-21, no.3 (where dated to the mid-1630s), and also pp.46-47, under nos.16x and 17x, p.52, under no.19x and p.54, under no.20x; Werner Sumowksi, Gemälde der Rembrandt-Schüler, Landau/Pfalz, 1983, Vol.I, p.203, under no.72; Peter van den Brink, ‘Uitmuntend Schilder in het Groot: De schilder en tekenaar Jacob Adriansz. -

The Leiden Collection

Slaughtered Pig ca. 1660–62 Attributed to Caspar Netscher oil on panel 36.7 x 30 cm CN-104 © 2017 The Leiden Collection Slaughtered Pig Page 2 of 8 How To Cite Wieseman, Marjorie E. "Slaughtered Pig." In The Leiden Collection Catalogue. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. New York, 2017. https://www.theleidencollection.com/archive/. This page is available on the site's Archive. PDF of every version of this page is available on the Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. Archival copies will never be deleted. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. © 2017 The Leiden Collection Slaughtered Pig Page 3 of 8 Seventeenth-century Netherlandish images of slaughtered oxen and pigs Comparative Figures have their roots in medieval depictions of the labors of the months, specifically November, the peak slaughtering season. The theme was given new life in the mid-sixteenth century through the works of the Flemish painters Pieter Aertsen (1508–75) and Joachim Beuckelaer (ca. 1533–ca. 1574), who incorporated slaughtered and disemboweled animals in their vivid renderings of abundantly supplied market stalls, and also explored the theme as an independent motif.[1] The earliest instances of the motif in the Northern Netherlands come only in the seventeenth century, possibly introduced by immigrants from the south. During the early 1640s, the theme of the slaughtered animal—split, splayed, and Fig 1. Barent Fabritius, suspended from the rungs of a wooden ladder—was taken up by (among Slaughtered Pig, 1665, oil on others) Adriaen (1610–85) and Isack (1621–49) van Ostade, who typically canvas, 101 x 79.5 cm, Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, situated the event in the dark and cavernous interior of a barn, stable, or Rotterdam, inv. -

December 16,1886

PORTLAND P !ESS I IAUU. Ill.l) JIM i»J, THURSDAY 1886. ISOB-VI^ 24._ PORTLAND, MORNING, DECEMBER 10, ffltKV/JfWffl PRICE THREE CENTS. OPIC1TAI, NOTICES. MMeBLLANlh. THE PORTLAND DAILY PRESS, FROM WASHINGTON. erous dangerous points, and finally madi MCQUADE CONVICTED. FOREICN. Published every day (Sundays excepted) by the this harbor. He was once beaten off by heac MAINE FOLK-LAND. old, had a place, a wife, and Immediate pros- PORTLAND PUBLISHING COMPANY, winds, but when the breeze changed h< pects of a larger family. Exchanoe Street, The Anti-Free Men Erv again attempted to affect an Although the .State has at no At 97 Portland, Me Ship Greatly extrance, ant The Great Trials Comes to a Mos t Cerir to be the Acres Held in Trust for Futuri > present pub- INSURANCE. this time succeeded. iny Beginning Watchful lic lands which It there are or OR. communications to with his cease may sell, eight E. Address all Weary B. at the Outlook. REED. couraged less watch and labor Conclusion. Towns. lie rau the schooner oi Satisfactory cf England’s Movements. MIX! TllOt'SAXD ACRES PORTLAND PUBLISHING CO. the flats and sought sleeo in his berth. Tbt which have and Botanic PRENTISS LORING’S AGENCY. vessel was found the not wholly passed to private Clairvoyant Physician The Bill Not by captain, who hat Story of the Celebrated 1 Likely to Be Considerec reached this Blnghan are have .N1EDICAI. BOOMS MAINE. city and dispatched a tug ir The Jury Agree on a Verdict In Four The r smoval of Chief Secret*..-/ ol parties. -

The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 3Rd Ed

Govaert Flinck (Kleve 1615 – 1660 Amsterdam) How to cite Bakker, Piet. “Govaert Flinck” (2017). In The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 3rd ed. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Lara Yeager-Crasselt. New York, 2020–. https://theleidencollection.com/artists/govaert- flinck/ (accessed September 27, 2021). A PDF of every version of this biography is available in this Online Catalogue's Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. © 2021 The Leiden Collection Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Govaert Flinck Page 2 of 8 Govaert Flinck was born in the German city of Kleve, not far from the Dutch city of Nijmegen, on 25 January 1615. His merchant father, Teunis Govaertsz Flinck, was clearly prosperous, because in 1625 he was appointed steward of Kleve, a position reserved for men of stature.[1] That Flinck would become a painter was not apparent in his early years; in fact, according to Arnold Houbraken, the odds were against his pursuit of that interest. Teunis considered such a career unseemly and apprenticed his son to a cloth merchant. Flinck, however, never stopped drawing, and a fortunate incident changed his fate. According to Houbraken, “Lambert Jacobsz, [a] Mennonite, or Baptist teacher of Leeuwarden in Friesland, came to preach in Kleve and visit his fellow believers in the area.”[2] Lambert Jacobsz (ca. 1598–1636) was also a famous Mennonite painter, and he persuaded Flinck’s father that the artist’s profession was a respectable one. Around 1629, Govaert accompanied Lambert to Leeuwarden to train as a painter.[3] In Lambert’s workshop Flinck met the slightly older Jacob Adriaensz Backer (1608–51), with whom he became lifelong friends. -

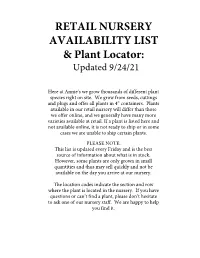

Retail Location List

RETAIL NURSERY AVAILABILITY LIST & Plant Locator: Updated 9/24/21 Here at Annie’s we grow thousands of different plant species right on site. We grow from seeds, cuttings and plugs and offer all plants in 4” containers. Plants available in our retail nursery will differ than those we offer online, and we generally have many more varieties available at retail. If a plant is listed here and not available online, it is not ready to ship or in some cases we are unable to ship certain plants. PLEASE NOTE: This list is updated every Friday and is the best source of information about what is in stock. However, some plants are only grown in small quantities and thus may sell quickly and not be available on the day you arrive at our nursery. The location codes indicate the section and row where the plant is located in the nursery. If you have questions or can’t find a plant, please don’t hesitate to ask one of our nursery staff. We are happy to help you find it. 9/24/2021 ww S ITEM NAME LOCATION Abutilon 'David's Red' 25-L Abutilon striatum "Redvein Indian Mallow" 21-E Abutilon 'Talini's Pink' 21-D Abutilon 'Victor Reiter' 24-H Acacia cognata 'Cousin Itt' 28-D Achillea millefolium 'Little Moonshine' 35-B ww S Aeonium arboreum 'Zwartkop' 3-E ww S Aeonium decorum 'Sunburst' 11-E ww S Aeonium 'Jack Catlin' 12-E ww S Aeonium nobile 12-E Agapanthus 'Elaine' 30-C Agapetes serpens 24-G ww S Agastache aurantiaca 'Coronado' 16-A ww S Agastache 'Black Adder' 16-A Agastache 'Blue Boa' 16-A ww S Agastache mexicana 'Sangria' 16-A Agastache rugosa 'Heronswood Mist' 14-A ww S Agave attenuata 'Ray of Light' 8-E ww S Agave bracteosa 3-E ww S Agave ovatifolia 'Vanzie' 7-E ww S Agave parryi var. -

The Developmentof Early Imperial Dress from the Tetrachs to The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. The Development of Early Imperial Dress from the Tetrarchs to the Herakleian Dynasty General Introduction The emperor, as head of state, was the most important and powerful individual in the land; his official portraits and to a lesser extent those of the empress were depicted throughout the realm. His image occurred most frequently on small items issued by government officials such as coins, market weights, seals, imperial standards, medallions displayed beside new consuls, and even on the inkwells of public officials. As a sign of their loyalty, his portrait sometimes appeared on the patches sown on his supporters’ garments, embossed on their shields and armour or even embellishing their jewelry. Among more expensive forms of art, the emperor’s portrait appeared in illuminated manuscripts, mosaics, and wall paintings such as murals and donor portraits. Several types of statues bore his likeness, including those worshiped as part of the imperial cult, examples erected by public 1 officials, and individual or family groupings placed in buildings, gardens and even harbours at the emperor’s personal expense. -

Jaarverslag 2008 (Pdf)

Jaarverslag 2008 inhoud 2 VAN PAULINE NAAR PAUL 8 PRESENTATIE 8 Tijdelijke tentoonstelling 14 Permanente tentoonstelling 20 EDUCATIE 34 COLLECTIE 52 ARCHEOLOGIE 54 MUSEUM WILLET -HOLTHUYSEN 58 INTERNATIONALE SAMENWERKING 62 Stichting Genootschap Amsterdams Historisch Museum 62 Het Genootschap Amsterdams Historisch Museum 65 Raad van Toezicht Stichting Amsterdams Historisch Museum 66 ANNUAL REPORT SUMMARY 68 DAG LIEVE PAULINE 74 BIJLAGEN 74 Bezoekersaantallen Van Pauline naar Paul Interview met scheidende directeur Per 1 januari 2009 is Paul Spies directeur van het Amsterdams Historisch Pauline Kruseman en komende Museum. De opvolger van Pauline Kruseman was hiervoor mededirecteur directeur Paul Spies door Teio van het Kunsthistorisch Advies- en Organisatiebureau d’arts, dat hij zelf Meedendorp. meer dan 20 jaar geleden met twee kompanen oprichtte. Aan het eind van 2008 keken Pauline en Paul gezamenlijk naar hun respectievelijk verleden en toekomende tijd in het Amsterdams Historisch Museum. Voordat Pauline ongeveer 18 jaar geleden het voormalige Burgerweeshuis binnentrok, werkte zij als zakelijk leider voor het kit/Tropenmuseum (20 jaar). Pauline: ‘Terugkijkend moet ik zeggen dat ik heb gewerkt voor de twee mooiste cultuurhistorische musea in Amsterdam. Ik heb heel bewust voor het werken in een cultuurhistorisch museum gekozen en voor het openbaar kunstbezit, daar heeft altijd mijn belangstelling gelegen. Ik vond het fantastisch om hier voor een mooie, eeuwenoude collectie te mogen zorgen en die in te zetten voor allerlei presentaties, om verhalen te vertellen over Amsterdam en de Amsterdammers. Mijn hart – en dat weet iedereen – ligt heel erg bij educatie. Het klinkt misschien heel ouderwets, maar ik ben erg voor l’éducation permanente. Of het Favoriete tentoonstellingen of aankopen tijdens haar directoraat wil ze nu voor kinderen of voor volwassenen is, hier kun je prachtige verhalen liever niet noemen, alle projecten zijn haar om diverse redenen even lief. -

Ontdek Schilder, Tekenaar Jan Victors

80890 Jan Victors man / Noord-Nederlands schilder, tekenaar Naamvarianten In dit veld worden niet-voorkeursnamen zoals die in bronnen zijn aangetroffen, vastgelegd en toegankelijk gemaakt. Dit zijn bijvoorbeeld andere schrijfwijzen, bijnamen of namen van getrouwde vrouwen met of juist zonder de achternaam van een echtgenoot. Victoor, Jan Victoors, Jan Victor, Jan Victors, Johan Victors, Johannes Victers, Joannes Fictor, Johannes Victors, Jan Louisz. Kwalificaties schilder, tekenaar was 'ziekentrooster' (visitor of the sick) Nationaliteit/school Noord-Nederlands Geboren Amsterdam 1619-06/1619-06-13 baptized 13 June 1619 Overleden Oost-Indië (hist.) 1676-09/1677-12 traveled as 'ziekentrooster' to East India in the service of the OIC and died there Familierelaties in dit veld wordt een familierelatie met één of meer andere kunstenaars vermeld. half-brother of Jacobus (Jacomo) Victors; notice of marriage 28 February 1642, 22 years old, with Jannetie Bellers; they had 7 children (De Vries 1886); father of Victor Victorsz. Deze persoon/entiteit in andere databases 137 treffers in RKDimages als kunstenaar 5 treffers in RKDlibrary als onderwerp 1104 treffers in RKDexcerpts als kunstenaar 42 treffers in RKDtechnical als onderzochte kunstenaar Verder zoeken in RKDartists& Geboren 1619-06 Sterfplaats Oost-Indië (hist.) Plaats van werkzaamheid Amsterdam Kwalificaties schilder Kwalificaties tekenaar Materiaal/techniek olieverf Onderwerpen genrevoorstelling Onderwerpen herbergscène Onderwerpen portret Onderwerpen christelijk religieuze voorstelling Onderwerpen boerengenre Biografische gegevens Werkzaam in Hier wordt vermeld waar de kunstenaar (langere tijd) heeft gewerkt en in welke periode. Ook relevante studiereizen worden hier vermeld. Amsterdam 1640 - 1676-01 c. 1640-1676 Relaties met andere kunstenaars Leerling van In dit veld worden namen van leraren of leermeesters vermeld. -

The Drawings of Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-1658) John Charleton

The Drawings of Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-1658) John Charleton Hawley III Jamaica Plain, MA M.A., History of Art, Institute of Fine Arts – New York University, 2010 B.A., Art History and History, College of William and Mary, 2008 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art and Architectural History University of Virginia May, 2015 _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................. i Acknowledgements.......................................................................................................................... ii Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: The Life of Cornelis Visscher .......................................................................................... 3 Early Life and Family .................................................................................................................... 4 Artistic Training and Guild Membership ...................................................................................... 9 Move to Amsterdam ................................................................................................................. -

1 © Australian Museum. This Material May Not Be Reproduced, Distributed

AMS564/002 – Scott sister’s second notebook, 1840-1862 © Australian Museum. This material may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, cached or otherwise used without permission from the Australian Museum. Text was transcribed by volunteers at the Biodiversity Volunteer Portal, a collaboration between the Australian Museum and the Atlas of Living Australia This is a formatted version of the transcript file from the second Scott Sisters’ notebook Page numbers in this document do not correspond to the notebook page numbers. The notebook was started from both ends at different times, so the transcript pages have been shuffled into approximately date order. Text in square brackets may indicate the following: - Misspellings, with the correct spelling in square brackets preceded by an asterisk rendersveu*[rendezvous] - Tags for types of content [newspaper cutting] - Spelled out abbreviations or short form words F[ield[. Nat[uralists] 1 AMS564/002 – Scott sister’s second notebook, 1840-1862 [Front cover] nulie(?) [start of page 130] [Scott Sisters’ page 169] Note Book No 2 Continued from first notebook No. 253. Larva (Noctua /Bombyx Festiva , Don n 2) found on the Crinum - 16 April 1840. Length 2 1/2 Incs. Ground color ^ very light blue, with numerous dark longitudinal stripes. 3 bright yellow bands, one on each side and one down the middle back - Head lightish red - a black velvet band, transverse, on the segment behind the front legs - but broken by the yellows This larva had a very offensive smell, and its habits were disgusting - living in the stem or in the thick part of the leaves near it, in considerable numbers, & surrounded by their accumulated filth - so that any touch of the Larva would soil the fingers.- It chiefly eat the thicker & juicier parts of the Crinum - On the 17 April made a very slight nest, underground, & some amongst the filth & leaves, by forming a cavity with agglutinated earth - This larva is showy - Drawing of exact size & appearance. -

Open Access Version Via Utrecht University Repository

Philosopher on the throne Stanisław August’s predilection for Netherlandish art in the context of his self-fashioning as an Enlightened monarch Magdalena Grądzka Philosopher on the throne Magdalena Grądzka Philosopher on the throne Stanisław August’s predilection for Netherlandish art in the context of his self-fashioning as an Enlightened monarch Magdalena Grądzka 3930424 March 2018 Master Thesis Art History of the Low Countries in its European Context University of Utrecht Prof. dr. M.A. Weststeijn Prof. dr. E. Manikowska 1 Philosopher on the throne Magdalena Grądzka Index Introduction p. 4 Historiography and research motivation p. 4 Theoretical framework p. 12 Research question p. 15 Chapters summary and methodology p. 15 1. The collection of Stanisław August 1.1. Introduction p. 18 1.1.1. Catalogues p. 19 1.1.2. Residences p. 22 1.2. Netherlandish painting in the collection in general p. 26 1.2.1. General remarks p. 26 1.2.2. Genres p. 28 1.2.3. Netherlandish painting in the collection per stylistic schools p. 30 1.2.3.1. The circle of Rubens and Van Dyck p. 30 1.2.3.2. The circle of Rembrandt p. 33 1.2.3.3. Italianate landscapists p. 41 1.2.3.4. Fijnschilders p. 44 1.2.3.5. Other Netherlandish artists p. 47 1.3. Other painting schools in the collection p. 52 1.3.1. Paintings by court painters in Warsaw p. 52 1.3.2. Italian paintings p. 53 1.3.3. French paintings p. 54 1.3.4. German paintings p. -

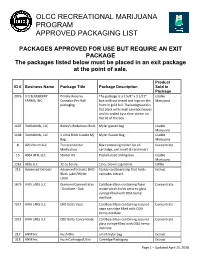

Olcc Recreational Marijuana Program Approved Packaging List

OLCC RECREATIONAL MARIJUANA PROGRAM APPROVED PACKAGING LIST PACKAGES APPROVED FOR USE BUT REQUIRE AN EXIT PACKAGE The packages listed below must be placed in an exit package at the point of sale. Product ID # Business Name Package Title Package Description Sold in Package 2076 3 D BLUEBERRY Private Reserve The package is a 2 5/8" x 3 1/12" Usable FARMS, INC. Cannabis Pre-Roll box with our brand and logo on the Marijuana packaging front in gold foil. The background is flat black with small cannabis leaves and its sealed by a clear sticker on the lid of the box. 1107 3Littlebirds, LLC Bobby's Bodacious Buds Mylar gusset bag Usable Marijuana 1108 3Littlebirds, LLC 3 Little Birds Usable Mj Mylar Gusset Bag Usable Bag Marijuana 8 420 Pharm LLC Transcendental Box containing holder for oil Concentrate Medication cartridge, cart inself & card insert 15 4964 BFH, LLC Starter Kit Pocket-sized sliding box. Usable Marijuana 1262 Ablis LLC 12 oz bottle 12 oz crown cap bottle Edible 213 Advanced Extracts Advanced Extracts BHO Sturdy cardboard slip that holds Extract Black Label/White cannabis extract. Label. 1679 AIRA LABS LLC Diamond Concentrates Cardboard box containing foam Concentrate - Distillate - Dab matte which holds secured glass syringe filled with ODA hemp distillate 1921 AIRA LABS LLC CBD Delta Vape Cardboard box containing secured Concentrate vape cartridge filled with ODA hemp distillate 1922 AIRA LABS LLC CBD Delta Concentrate Cardboard box containing secured Concentrate glass syringe filled with ODA hemp distillate 217 ANM Inc. Hush Bho small mylar bag Extract 218 ANM Inc.