Full Screen View

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heavyweight Champion Jack Johnson: His Omaha Image, a Public Reaction Study

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Heavyweight Champion Jack Johnson: His Omaha Image, A Public Reaction Study Full Citation: Randy Roberts, “Heavyweight Champion Jack Johnson: His Omaha Image, A Public Reaction Study,” Nebraska History 57 (1976): 226-241 URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1976 Jack_Johnson.pdf Date: 11/17/2010 Article Summary: Jack Johnson, the first black heavyweight boxing champion, played an important role in 20th century America, both as a sports figure and as a pawn in race relations. This article seeks to “correct” his popular image by presenting Omaha’s public response to his public and private life as reflected in the press. Cataloging Information: Names: Eldridge Cleaver, Muhammad Ali, Joe Louise, Adolph Hitler, Franklin D Roosevelt, Budd Schulberg, Jack Johnson, Stanley Ketchel, George Little, James Jeffries, Tex Rickard, John Lardner, William -

Eugenicists, White Supremacists, and Marcus Garvey in Virginia, 1922-1927

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2001 Strange Bedfellows: Eugenicists, White Supremacists, and Marcus Garvey in Virginia, 1922-1927 Sarah L. Trembanis College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Trembanis, Sarah L., "Strange Bedfellows: Eugenicists, White Supremacists, and Marcus Garvey in Virginia, 1922-1927" (2001). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624397. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-eg2s-rc14 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STRANGE BEDFELLOWS- Eugenicists, White Supremacists, and Marcus Garvey in Virginia, 1922-1927. A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Sarah L. Trembanis 2001 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Sarah L. Trembanis Approved, August 2001 (?L Ub Kimbe$y L. Phillips 'James McCord TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgments iv Abstract v Introduction 2 Chapter 1: Dealing with “Mongrel Virginians” 25 Chapter 2: An Unlikely Alliance 47 Conclusion 61 Appendix One: An Act to Preserve Racial Integrity 64 Appendix Two: Model Eugenical Sterilization Law 67 Bibliography 74 Vita 81 iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First of all, I would like to thank my advisor, Professor Kimberly Phillips, for all of her invaluable suggestions and assistance. -

I Think a Good Deal in Terms of the Power of Black People in the World…That’S Why Africa Means So Much to Me

Returning Home: The Makings of a Repatriate Consciousness “Like Sisyphus, the King of Corinth in Greek Mythology, who was punished in Hades by having to push a boulder up a hill only to have it roll back down time after time, the Afro-American has been repeatedly disappointed in his ascent to freedom. In the African he recognizes a fellow Sisyphus. Pushing together they might just reach the hilltop, perhaps even the mountaintop of which Martin Luther King spoke so eloquently.”1 Hope Steinman-Iacullo SIT Fall 2007 Ghana: History and Culture of the African Diaspora Advisor: Dr. K.B. Maison 1 Robert G. Weisbord. Ebony Kinship: Africa, Africans, and the Afro American. (London: Greenwood Press Inc, 1973), 220. 2 Returning Home: The Makings of a Repatriate Consciousness Index: Acknowledgements………………………………………………………….3 Abstract……………………………………………………………………4-5 Introduction and Background……………………………………………6-14 Methodology……………………………………………………………15-23 Chapter I: The Power of Naming in Expressing Identity, Lineage, and an African Connection………………………………..24-28 Chapter II: Reasons for Returning……………………………………..…28 Part A: Escaping Fear and Escaping Stress……………….28-32 Part B: The Personal is the Political: Political Ideology and the Shaping of a Repatriate Consciousness…………………...32-36 Part C: Spiritual Reflection and Meditation in the Repatriate Experience……………………………………………..36-40 Chapter III: Difficulties in the Experience of Repatriation……………..40-46 Chapter IV: The Joys of Returning Home: A Conclusion……………...46-50 Suggestions for Further Study……………………………………………...51 Bibliography………………………………………………………………52 3 Acknowledgements: First and foremost I would like to thank my family for supporting me in coming to Ghana and for being there for me through all of my ups and downs. -

A RESOLUTION to Commemorate the 77Th Birthday of Civil Rights Activist Malcolm X

Filed for intro on 05/08/2002 HOUSE RESOLUTION 277 By Brooks A RESOLUTION to commemorate the 77th birthday of civil rights activist Malcolm X. WHEREAS, it is fitting that this General Assembly should pause in its deliberations and recognize those outstanding civil rights leaders who, through their exemplary efforts, struggled to realize the noble precepts of liberty and equality for all people; and WHEREAS, one such noteworthy advocate of social justice was Malcolm X whose 77th birthday will be commemorated on May 19, 2002; and WHEREAS, a native of Omaha, Nebraska, Malcolm Little was born to loving parents, Earl and Louis Norton Little on May 19, 1925; and WHEREAS, his mother diligently served as a homemaker raising eight children, while his father was an outspoken Baptist minister and supporter of Black Nationalist leader, Marcus Garvey; and WHEREAS, Earl Little, a civil rights activist, was forced to move his family twice, before Malcolm was four, to avoid persecution for his beliefs on racial equality; and HR0277 01467385 -1- WHEREAS, in 1929, Earl Little was killed and Louise Little suffered an emotional breakdown sometime later and was committed to a mental institution; and WHEREAS, these tragic events forced Malcolm and his siblings to enter various foster homes and orphanages; and WHEREAS, an intelligent and focused student, Malcolm excelled academically throughout junior high school and ranked at the top of his class; and WHEREAS, his ambition as a young man was to become an attorney; however, this dream was short-lived, as he -

Notions of Beauty & Sexuality in Black Communities in the Caribbean and Beyond

fNotions o Beauty & Sexuality in Black Communities IN THE CARIBBEAN AND BEYOND VOL 14 • 2016 ISSN 0799-1401 Editor I AN B OX I LL Notions of Beauty & Sexuality in Black Communities in the Caribbean and Beyond GUEST EDITORS: Michael Barnett and Clinton Hutton IDEAZ Editor Ian Boxill Vol. 14 • 2016 ISSN 0799-1401 © 2016 by Centre for Tourism & Policy Research & Ian Boxill All rights reserved Ideaz-Institute for Intercultural and Comparative Research / Ideaz-Institut für interkulturelle und vergleichende Forschung Contact and Publisher: www.ideaz-institute.com IDEAZ–Journal Publisher: Arawak publications • Kingston, Jamaica Credits Cover photo –Courtesy of Lance Watson, photographer & Chyna Whyne, model Photos reproduced in text –Courtesy of Clinton Hutton (Figs. 2.1, 4.4, 4.5, G-1, G-2, G-5) David Barnett (Fig. 4.1) MITS, UWI (Figs. 4.2, 4.3) Lance Watson (Figs. 4.6, 4.7, G.3, G-4) Annie Paul (Figs. 6.1, 6.2, 6.3) Benjamin Asomoah (Figs. G-6, G-7) C O N T E N T S Editorial | v Acknowledgments | ix • Articles Historical Sociology of Beauty Practices: Internalized Racism, Skin Bleaching and Hair Straightening | Imani M. Tafari-Ama 1 ‘I Prefer The Fake Look’: Aesthetically Silencing and Obscuring the Presence of the Black Body | Clinton Hutton 20 Latin American Hyper-Sexualization of the Black Body: Personal Narratives of Black Female Sexuality/Beauty in Quito, Ecuador | Jean Muteba Rahier 33 The Politics of Black Hair: A Focus on Natural vs Relaxed Hair for African-Caribbean Women | Michael Barnett 69 Crossing Borders, Blurring Boundaries: -

Black Power, the Black Panthers, and the American Creed

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 2007 Radicalism in American Political Thought : Black Power, the Black Panthers, and the American Creed Christopher Thomas Cooney Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the African American Studies Commons, Political Science Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, and the United States History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Cooney, Christopher Thomas, "Radicalism in American Political Thought : Black Power, the Black Panthers, and the American Creed" (2007). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3238. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.3228 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. THESIS APPROVAL The abstract and thesis of Chri stopher Thomas Cooney for the Master of Science in Political Science were presented July 3 1, 2007, and accepted by the thesis committee and the department. COMMITTEE APPROVALS: Cr~ cyr, Chai( David Kinsell a Darrell Millner Representative of the Office of Graduate Studies DEPARTMENT APPROVAL: I>' Ronald L. Tammen, Director Hatfield School of Government ABSTRACT An abstract of the thesis of Christopher Thomas Cooney for the Master of Science in Political Science presented July 31, 2007. Title: Radicalism in American Political Thought: Black Power, the Black Panthers, and the American Creed. American Political Thought has presented somewhat of a challenge to many because of the conflict between the ideals found within the "American Creed" and the reality of America's treatment of ethnic and social minorities. -

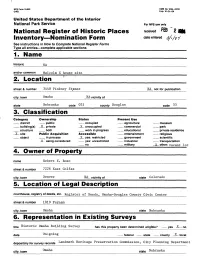

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form 1. Name

NPS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic NA and/or common Malcolm X house site 2. Location street & number 3448 Pinkney NA not for publication city, town Omaha _NA vicinity of state Nebraska code 031 county Douglas code 55 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use _ district public occupied agriculture museum building(s) X private X unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence _J^site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process X yes: restricted government scientific _JL." being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military _X_ other: vacant lo 4. Owner of Property name Robert E. Rose street & number 7226 East Coif ax city, town Denver NA_ vicinity of state Colorado 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Register of Deeds, Qmaha-Douglas County Civic Center street & number 1819 Farnam city, town Omaha state Nebraska 6. Representation in Existing Surveys tjtje Historic Omaha Building Survey has this property been determined eligible? yes X no date On-going federal state __ county _JL_ local depository for survey records Landmark: Heritage Preservation Commission, City Planning Department city, town Omaha state Nebraska 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent _ deteriorated unaltered X original site . ruins _X_ altered moved date NA ** "" f" X . unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance The childhood home of Malcolm X was in a lower income neighborhood of small single family homes of predominately black families. -

Aims and Objects of Movement for Solution of Negro Problem ______1924 *

National Humanities Center Resource Toolbox The Making of African American Identity: Vol. III, 1917-1968 __________________Marcus Garvey UCLA African Studies Center Aims and Objects of Movement for Solution of Negro Problem _________1924 * enerally the public is kept misinformed of the truth G surrounding new movements of reform. Very seldom, if ever, reformers get the truth told about them and their movements. Because of this natural attitude, the Universal Negro Improvement Association has been greatly handicapped in its work, causing thereby one of the most liberal and helpful human movements of the twentieth century to be held up to ridicule by those who take pride in poking fun at anything not already successfully established. The white man of America has become the natural leader of the world. He, because of his exalted position, is called upon to help in all human efforts. From nations to individuals the appeal is made to him for aid in all things affecting humanity, so, naturally, there can be no great mass movement or change without first acquainting the leader on whose sympathy and advice the world moves. It is because of this, and more so because of a desire to be Marcus Garvey as commander in chief Christian friends with the white race, why I explain the aims of the Universal African Legion and objects of the Universal Negro Improvement Association. The Universal Negro Improvement Association is an organization among Negroes that is seeking to improve the condition of the race, with the view of establishing a nation in Africa where Negroes will be given the opportunity to develop by themselves, without creating the hatred and animosity that now exist in countries of the white race through Negroes rivaling them for the highest and best positions in government, politics, society and industry. -

Worksheets Malcolm X Facts

Malcolm X Worksheets Malcolm X Facts Malcolm X is a prominent African-American civil rights activist and Muslim minister who introduced black nationalism and racial pride during the 1950s and 60s. ★ Malcolm X was born on May 19, 1925, in Omaha, Nebraska. He was fourth of the eight children of Louise and Earl Little. His father was an avid supporter and member of the Universal Negro Improvement Movement. He supported Marcus Garvey, a known black nationalist leader. Malcolm X’s family experienced number of harassments from the Ku Klux Klan and other factions such as the Black Legion due to Earl’s civil rights activism. ★ When young Malcolm was four, his family moved to Milwaukee after a hooded party of Ku Klux Klan riders raided their home in Omaha. In 1929, racist mob set their house on fire leading them to move again to East Lansing. Malcolm X Facts ★ In 1931, Malcolm’s father was found dead in the street across the municipal streetcar tracks. Six years later, his mother was admitted to a mental institution due to trauma and depression where she stayed for 26 years. ★ By 1938, Malcolm X was sent to the juvenile detention home in mason, Michigan. He stayed with a white couple who treated him well. Later on, he attended the Mason High School where he excelled both academically and socially. ★ At the age of 15, Malcolm dropped out of school after his encounter with his English teacher. Malcolm thought of himself of being a lawyer but the teacher told him to be realistic and consider carpentry instead. -

Malcolm X and the Psychology of "Barn Burning"

International Bulletin of Political Psychology Volume 2 Issue 8 Article 2 6-20-1997 Malcolm X and the Psychology of "Barn Burning" IBPP Editor [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.erau.edu/ibpp Part of the Mental Disorders Commons, Psychiatric and Mental Health Commons, and the Psychiatry Commons Recommended Citation Editor, IBPP (1997) "Malcolm X and the Psychology of "Barn Burning"," International Bulletin of Political Psychology: Vol. 2 : Iss. 8 , Article 2. Available at: https://commons.erau.edu/ibpp/vol2/iss8/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Bulletin of Political Psychology by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Editor: Malcolm X and the Psychology of "Barn Burning" International Bulletin of Political Psychology Title: Malcolm X and the Psychology of "Barn Burning" Author: Editor Volume: 2 Issue: 8 Date: 1997-06-20 Keywords: Icarus Complex, Revolution, Malcolm X Abstract. This article provides historical and psychological data that may bear on the recent firesetting tragedy involving Dr. Betty Shabbaz, Malcolm X's widow, and his grandson, Malcolm Shabbaz. By now it's old news that Malcolm Shabazz, the grandson of Malcolm X, allegedly set a fire in the apartment of his grandmother, Dr. Betty Shabbaz--Malcolm X's widow. The fire occurred on the night of June 1, 1997 and left Dr. Shabbaz, head of the office of institutional advancement at Medgar Evers College in New York City, with burns over 80% of her body. -

Marcus G Ar Ve Y Papers

THE MARCUS G AR VE Y AND UNIVERSAL NEGRO IMPROVEMENT ASSOCIATION PAPERS SUPPORTED BY The National Endowment for the Humanities The National Historical Publications and Records Commission SPONSORED BY The University of California, Los Angeles EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD HERBERT APTHEKER MARY FRANCES BERRY JOHN W. BLASSINGAME JOHN HENRIK CLARKE STANLEY COBEN EDMUND DAVID CRONON IAN DUFFIELD E. U. ESSIEN-UDOM IMANUEL GEISS VINCENT HARDING RICHARD HART THOMAS L. HODGKINI" ARTHUR S. LINK GEORGE A. SHEPPERSON MICHAEL R. WINSTON Marcus Garvey and the UNIA in Convention THE MARCUS GARVEY AND UNIVERSAL NEGRO IMPROVEMENT ASSOCIATION PAPERS Volume II 27 August 1919-31 August 1920 Robert A. Hill Editor Emory J. Tolbert Senior Editor Deborah Forczek Assistant Editor University of California Press Berkeley Los Angeles London University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England This volume has been funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities, an independent federal agency. The volume has also been supported by the National Historical Publications and Records Commission and the University of California, Los Angeles. Documents in this volume from the Public Record Office are © British Crown Copyright 1920 and are published by permission of the Controller of Her Britannic Majesty's Stationery Office. Designed by Linda Robertson and set in Galliard type. Copyright ©1983 by The Regents of the University of California Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Main entry under title: The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Association papers. 1. Garvey, Marcus, 1887-1940. 2. Universal Negro Improvement Association—History—Sources. 3. Black power—United States— History—Sources. -

The New Afro-American Nationalism

THE NEW AFRO-AMERICAN NATIONALISM JOHN HENRIK CLARKE THE FEBRUARY, ig6i, riot in the gallery of the United Nations in protest against the foul and cowardly murder of Patrice Lu- mumba introduced the new Afro-American Nationalism. This na- tionalism is only a new manifestation of old grievances with deep roots. Nationalism, and a profound interest in Africa, actually started among Afro-Americans during the latter part of the nine- teenth century. Therefore, the new Afro-American nationalism is really not new. The demonstrators in the United Nations gallery interpreted the murder of Lumumba as the international lynching of a black man on the altar of colonialism and white supremacy. Suddenly, to them at least, Lumumba became Emmett Till and all of the other black victims of lynch law and the mob. The plight of the Africans still fighting to throw off the joke of colonialism and the plight of the Afro-Americans, still waiting for a rich, strong and boastful nation to redeem the promise of freedom and citizenship became one and the same. Through their action the U.N. dem- onstrators announced their awareness of the fact that they were far from being free and a long fight still lay ahead of them. The short and unhappy life of Patrice Lumumba announced the same thing about Africa. Belatedly, some American officials began to realize that the for- eign policy of this country will be affected if the causes of the long brooding dissatisfaction among Afro-Americans are not dealt with effectively. Others, quick to draft unfavorable conclusions and compound misconceptions, interpretated this action as meaning there was more Afro-American interest in African affairs than in 285 Reprinted from FREEDOMWAYS, Vol .