Key to Common Mammal Skulls Kerry Wixted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MINNESOTA MUSTELIDS Young

By Blane Klemek MINNESOTA MUSTELIDS Young Naturalists the Slinky,Stinky Weasel family ave you ever heard anyone call somebody a weasel? If you have, then you might think Hthat being called a weasel is bad. But weasels are good hunters, and they are cunning, curious, strong, and fierce. Weasels and their relatives are mammals. They belong to the order Carnivora (meat eaters) and the family Mustelidae, also known as the weasel family or mustelids. Mustela means weasel in Latin. With 65 species, mustelids are the largest family of carnivores in the world. Eight mustelid species currently make their homes in Minnesota: short-tailed weasel, long-tailed weasel, least weasel, mink, American marten, OTTERS BY DANIEL J. COX fisher, river otter, and American badger. Minnesota Conservation Volunteer May–June 2003 n e MARY CLAY, DEMBINSKY t PHOTO ASSOCIATES r mammals a WEASELS flexible m Here are two TOM AND PAT LEESON specialized mustelid feet. b One is for climb- ou can recognize a ing and the other for hort-tailed weasels (Mustela erminea), long- The long-tailed weasel d most mustelids g digging. Can you tell tailed weasels (M. frenata), and least weasels eats the most varied e food of all weasels. It by their tubelike r which is which? (M. nivalis) live throughout Minnesota. In also lives in the widest Ybodies and their short Stheir northern range, including Minnesota, weasels variety of habitats and legs. Some, such as badgers, hunting. Otters and minks turn white in winter. In autumn, white hairs begin climates across North are heavy and chunky. Some, are excellent swimmers that hunt to replace their brown summer coat. -

Cornell's Naturalist Outreach Presents: Rodents: Nutty Adaptations For

Cornell’s Naturalist Outreach Presents: Rodents: Nutty Adaptations for Survival By: Ashley Eisenhauer What is a rodent? Rodents are a very diverse, interesting group of animals. They can be found on every continent except for Antarctica. The largest rodent is the Capybara (left picture) from South America, and the smallest—about the size of a quarter—is the pygmy jerboa (right picture), indigenous to Africa. The feature all rodents share are continuously growing, gnawing teeth. This is what causes them to constantly chew on things, because they need to grind their teeth to keep them the proper size and sharpen them. Their other features, such as their vision, hearing, fur, feet, tails, sociality, and survival methods during the winter vary from species to species. Exploring the diversity of rodents is an effective way of demonstrating adaptations in animals. The rodents I will be talking about with students are the eastern gray squirrel, northern flying squirrel, woodchuck/groundhog, eastern chipmunk, and chinchilla. All of these are indigenous to New York, except the chinchilla which is from the Andes Mountains in South America. I will be bringing my pet chinchillas to my presentations to show how certain aspects of chinchillas are different from the rodents that live here in New York because of the climate difference. Some of these differences include larger ears for heat dissipation, thick fur for cold nights, and large herd sociality. Local critters that are often mistaken as rodents are rabbits, which are actually Lagomorphs. This is a common misconception because they also have continuously growing teeth and are constantly chewing on something. -

Veterinary Dentistry Extraction

Veterinary Dentistry Extraction Introduction The extraction of teeth in the dog and cat require specific skills. In this chapter the basic removal technique for a single rooted incisor tooth is developed for multi-rooted and canine teeth. Deciduous teeth a nd feline teeth, particularly those affected by odontoclastic resorptive lesions, also require special attention. Good technique requires careful planning. Consider if extraction is necessary, and if so, how is it best accomplished. Review the root morphology and surrounding structures using pre-operative radiographs. Make sure you have all the equipment you need, and plan pre and post-operative management. By the end of this chapter you should be able to: ü Know the indications for extracting a tooth ü Unders tand the differing root morphology of dog and cat teeth ü Be able to select an extraction technique and equipment for any individual tooth ü Know of potential complications and how to deal with them ü Be able to apply appropriate analgesic and other treatment. Indications for Extraction Mobile Teeth Mobile teeth are caused by advanced periodontal disease and bone loss. Crowding of Teeth Retained deciduous canine. Teeth should be considered for extraction when they are interfering with occlusion or crowding others (e.g. supernumerary teeth). Retained Deciduous Teeth Never have two teeth of the same type in the same place at the same time. This is the rule of dental succession. Teeth in the Line of a Fracture Consider extracting any teeth in the line of a fracture of the mandible or maxilla. Teeth Destroyed by Disease Teeth ruined by advanced caries, feline neck lesions etc. -

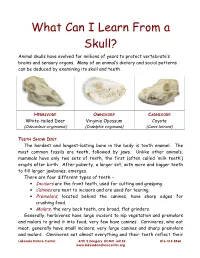

What Can I Learn from a Skull? Animal Skulls Have Evolved for Millions of Years to Protect Vertebrate’S Brains and Sensory Organs

What Can I Learn From a Skull? Animal skulls have evolved for millions of years to protect vertebrate’s brains and sensory organs. Many of an animal’s dietary and social patterns can be deduced by examining its skull and teeth. HERBIVORE OMNIVORE CARNIVORE White-tailed Deer Virginia Opossum Coyote (Odocoileus virginianus) (Didelphis virginiana) (Canis latrans) TEETH SHOW DIET . The hardest and longest-lasting bone in the body is tooth enamel. The most common fossils are teeth, followed by jaws. Unlike other animals, mammals have only two sets of teeth, the first (often called ‘milk teeth’) erupts after birth. After puberty, a larger set, with more and bigger teeth to fill larger jawbones, emerges. There are four different types of teeth – • Incisors are the front teeth, used for cutting and grasping. • Canines are next to incisors and are used for tearing. • Premolars , located behind the canines, have sharp edges for crushing food. • Molars , the very back teeth, are broad, flat grinders. Generally, herbivores have large incisors to nip vegetation and premolars and molars to grind it into food; very few have canines. Carnivores, who eat meat, generally have small incisors, very large canines and sharp premolars and molars. Omnivores eat almost everything and their teeth reflect their Lakeside Nature Center 4701 E Gregory, KCMO 64132 816-513-8960 www.lakesidenaturecenter.org preferences; they have all four types of teeth. In fact, if you’d like to see an excellent example of an omnivore’s teeth, look in the mirror. EYE PLACEMENT IDENTIFIES PREDATORS . Carnivores generally have large eyes, placed so that the eyes look forward and the areas of vision of the two eyes overlap. -

Shape Evolution and Sexual Dimorphism in the Mandible of the Dire Wolf, Canis Dirus, at Rancho La Brea Alexandria L

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2014 Shape evolution and sexual dimorphism in the mandible of the dire wolf, Canis Dirus, at Rancho la Brea Alexandria L. Brannick [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the Animal Sciences Commons, and the Paleontology Commons Recommended Citation Brannick, Alexandria L., "Shape evolution and sexual dimorphism in the mandible of the dire wolf, Canis Dirus, at Rancho la Brea" (2014). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 804. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SHAPE EVOLUTION AND SEXUAL DIMORPHISM IN THE MANDIBLE OF THE DIRE WOLF, CANIS DIRUS, AT RANCHO LA BREA A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Biological Sciences by Alexandria L. Brannick Approved by Dr. F. Robin O’Keefe, Committee Chairperson Dr. Julie Meachen Dr. Paul Constantino Marshall University May 2014 ©2014 Alexandria L. Brannick ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I thank my advisor, Dr. F. Robin O’Keefe, for all of his help with this project, the many scientific opportunities he has given me, and his guidance throughout my graduate education. I thank Dr. Julie Meachen for her help with collecting data from the Page Museum, her insight and advice, as well as her support. I learned so much from Dr. -

Mammalia, Felidae, Canidae, and Mustelidae) from the Earliest Hemphillian Screw Bean Local Fauna, Big Bend National Park, Brewster County, Texas

Chapter 9 Carnivora (Mammalia, Felidae, Canidae, and Mustelidae) From the Earliest Hemphillian Screw Bean Local Fauna, Big Bend National Park, Brewster County, Texas MARGARET SKEELS STEVENS1 AND JAMES BOWIE STEVENS2 ABSTRACT The Screw Bean Local Fauna is the earliest Hemphillian fauna of the southwestern United States. The fossil remains occur in all parts of the informal Banta Shut-in formation, nowhere very fossiliferous. The formation is informally subdivided on the basis of stepwise ®ning and slowing deposition into Lower (least fossiliferous), Middle, and Red clay members, succeeded by the valley-®lling, Bench member (most fossiliferous). Identi®ed Carnivora include: cf. Pseudaelurus sp. and cf. Nimravides catocopis, medium and large extinct cats; Epicyon haydeni, large borophagine dog; Vulpes sp., small fox; cf. Eucyon sp., extinct primitive canine; Buisnictis chisoensis, n. sp., extinct skunk; and Martes sp., marten. B. chisoensis may be allied with Spilogale on the basis of mastoid specialization. Some of the Screw Bean taxa are late survivors of the Clarendonian Chronofauna, which extended through most or all of the early Hemphillian. The early early Hemphillian, late Miocene age attributed to the fauna is based on the Screw Bean assemblage postdating or- eodont and predating North American edentate occurrences, on lack of de®ning Hemphillian taxa, and on stage of evolution. INTRODUCTION southwestern North America, and ®ll a pa- leobiogeographic gap. In Trans-Pecos Texas NAMING AND IMPORTANCE OF THE SCREW and adjacent Chihuahua and Coahuila, Mex- BEAN LOCAL FAUNA: The name ``Screw Bean ico, they provide an age determination for Local Fauna,'' Banta Shut-in formation, postvolcanic (,18±20 Ma; Henry et al., Trans-Pecos Texas (®g. -

Vivid Dreams/ Problems Sleeping: Nausea/Upset Stomach: Itching/Rash

Addressing NRT Barriers • Assess the severity of symptoms (Is it tolerable?). • Assess Hx: onset, duration and any troubleshooting that has already taken place. If indicated, get history of these symptoms when not taking these medications. You may also ask how Pt. would normally treat these symptoms. • If symptoms are tolerable àdevelop troubleshooting plan with Pt. Inform Pt. that many symptoms will go away after a few days. Reassess at next visit, but ask Pt. to call if symptoms persist/worsen or become intolerable before next call/visit. • If symptoms are not tolerableàconsider changing products or dosages as applicable. Consult study physician, as needed. Refer Pt. to their personal physician, if needed (e.g., prescription strength creams). • All potential cardiac symptoms should be promptly reported to study physician. Advise Pt. to discontinue NRT when indicated or instructed by study physician. Vivid Dreams/ Problems Sleeping: - Assess if sleep is being disrupted. Is night waking normal for Pt. – what is Pts.’ normal routine? - May try taking patch off at night, keeping in mind cravings may be stronger in the AM. After a couple of nights, try again to wear patch overnight. If using more than 1 patch, may consider only wearing 1 at night. - May try removing patch at night and putting on 2 hours before waking, especially when early morning waking is part of routine. Otherwise, can set an alarm, put on patch, and go back to sleep. - Regulate eating and sleeping patterns and use sleep hygiene tips (relaxation training, avoid caffeine). - Do not smoke or use short-acting NRT within 1-2 hours of bedtime (especially if sleep initiation is the major complaint.) Nausea/upset stomach: - Ask if nausea is only after using gum/lozenge or also after smoking a cigarette. -

Tooth Size Proportions Useful in Early Diagnosis

#63 Ortho-Tain, Inc. 1-800-541-6612 Tooth Size Proportions Useful In Early Diagnosis As the permanent incisors begin to erupt starting with the lower central, it becomes helpful to predict the sizes of the other upper and lower adult incisors to determine the required space necessary for straightness. Although there are variations in the mesio-distal widths of the teeth in any individual when proportions are used, the sizes of the unerupted permanent teeth can at least be fairly accurately pre-determined from the mesio-distal measurements obtained from the measurements of already erupted permanent teeth. As the mandibular permanent central breaks tissue, a mesio-distal measurement of the tooth is taken. The size of the lower adult lateral is obtained by adding 0.5 mm.. to the lower central size (see a). (a) Width of lower lateral = m-d width of lower central + 0.5 mm. The sizes of the upper incisors then become important as well. The upper permanent central is 3.25 mm.. wider than the lower central (see b). (b) Size of upper central = m-d width of lower central + 3.25 mm. The size of the upper lateral is 2.0 mm. smaller mesio-distally than the maxillary central (see c), and 1.25 mm. larger than the lower central (see d). (c) Size of upper lateral = m-d width of upper central - 2.0 mm. (d) Size of upper lateral = m-d width of lower central + 1.25 mm. The combined mesio-distal widths of the lower four adult incisors are four times the width of the mandibular central plus 1.0 mm. -

Is the Skeleton Male Or Female? the Pelvis Tells the Story

Activity: Is the Skeleton Male or Female? The pelvis tells the story. Distinct features adapted for childbearing distinguish adult females from males. Other bones and the skull also have features that can indicate sex, though less reliably. In young children, these sex-related features are less obvious and more difficult to interpret. Subtle sex differences are detectable in younger skeletons, but they become more defined following puberty and sexual maturation. What are the differences? Compare the two illustrations below in Figure 1. Female Pelvic Bones Male Pelvic Bones Broader sciatic notch Narrower sciatic notch Raised auricular surface Flat auricular surface Figure 1. Female and male pelvic bones. (Source: Smithsonian Institution, illustrated by Diana Marques) Figure 2. Pelvic bone of the skeleton in the cellar. (Source: Smithsonian Institution) Skull (Cranium and Mandible) Male Skulls Generally larger than female Larger projections behind the Larger brow ridges, with sloping, ears (mastoid processes) less rounded forehead Square chin with a more vertical Greater definition of muscle (acute) angle of the jaw attachment areas on the back of the head Figure 3. Male skulls. (Source: Smithsonian Institution, illustrated by Diana Marques) Female Skulls Smoother bone surfaces where Smaller projections behind the muscles attach ears (mastoid processes) Less pronounced brow ridges, Chin more pointed, with a larger, with more vertical forehead obtuse angle of the jaw Sharp upper margins of the eye orbits Figure 4. Female skulls. (Source: Smithsonian Institution, illustrated by Diana Marques) What Do You Think? Comparing the skull from the cellar in Figure 5 (below) with the illustrated male and female skulls in Figures 3 and 4, write Male or Female to note the sex depicted by each feature. -

Facial Image Comparison Feature List for Morphological Analysis

Disclaimer: As a condition to the use of this document and the information contained herein, the Facial Identification Scientific Working Group (FISWG) requests notification by e-mail before or contemporaneously to the introduction of this document, or any portion thereof, as a marked exhibit offered for or moved into evidence in any judicial, administrative, legislative, or adjudicatory hearing or other proceeding (including discovery proceedings) in the United States or any foreign country. Such notification shall include: 1) the formal name of the proceeding, including docket number or similar identifier; 2) the name and location of the body conducting the hearing or proceeding; and 3) the name, mailing address (if available) and contact information of the party offering or moving the document into evidence. Subsequent to the use of this document in a formal proceeding, it is requested that FISWG be notified as to its use and the outcome of the proceeding. Notifications should be sent to: Redistribution Policy: FISWG grants permission for redistribution and use of all publicly posted documents created by FISWG, provided the following conditions are met: Redistributions of documents, or parts of documents, must retain the FISWG cover page containing the disclaimer. Neither the name of FISWG, nor the names of its contributors, may be used to endorse or promote products derived from its documents. Any reference or quote from a FISWG document must include the version number (or creation date) of the document and mention if the document is in a draft status. Version 2.0 2018.09.11 Facial Image Comparison Feature List for Morphological Analysis 1. -

The Cat Mandible (II): Manipulation of the Jaw, with a New Prosthesis Proposal, to Avoid Iatrogenic Complications

animals Review The Cat Mandible (II): Manipulation of the Jaw, with a New Prosthesis Proposal, to Avoid Iatrogenic Complications Matilde Lombardero 1,*,† , Mario López-Lombardero 2,†, Diana Alonso-Peñarando 3,4 and María del Mar Yllera 1 1 Unit of Veterinary Anatomy and Embryology, Department of Anatomy, Animal Production and Clinical Veterinary Sciences, Faculty of Veterinary Sciences, Campus of Lugo—University of Santiago de Compostela, 27002 Lugo, Spain; [email protected] 2 Engineering Polytechnic School of Gijón, University of Oviedo, 33203 Gijón, Spain; [email protected] 3 Department of Animal Pathology, Faculty of Veterinary Sciences, Campus of Lugo—University of Santiago de Compostela, 27002 Lugo, Spain; [email protected] 4 Veterinary Clinic Villaluenga, calle Centro n◦ 2, Villaluenga de la Sagra, 45520 Toledo, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-982-822-333 † Both authors contributed equally to this manuscript. Simple Summary: The small size of the feline mandible makes its manipulation difficult when fixing dislocations of the temporomandibular joint or mandibular fractures. In both cases, non-invasive techniques should be considered first. When not possible, fracture repair with internal fixation using bone plates would be the best option. Simple jaw fractures should be repaired first, and caudal to rostral. In addition, a ventral approach makes the bone fragments exposure and its manipulation easier. However, the cat mandible has little space to safely place the bone plate screws without damaging the tooth roots and/or the mandibular blood and nervous supply. As a consequence, we propose a conceptual model of a mandibular prosthesis that would provide biomechanical Citation: Lombardero, M.; stabilization, avoiding any unintended (iatrogenic) damage to those structures. -

Study Guide Medical Terminology by Thea Liza Batan About the Author

Study Guide Medical Terminology By Thea Liza Batan About the Author Thea Liza Batan earned a Master of Science in Nursing Administration in 2007 from Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. She has worked as a staff nurse, nurse instructor, and level department head. She currently works as a simulation coordinator and a free- lance writer specializing in nursing and healthcare. All terms mentioned in this text that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. Use of a term in this text shouldn’t be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. Copyright © 2017 by Penn Foster, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be mailed to Copyright Permissions, Penn Foster, 925 Oak Street, Scranton, Pennsylvania 18515. Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS INSTRUCTIONS 1 READING ASSIGNMENTS 3 LESSON 1: THE FUNDAMENTALS OF MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY 5 LESSON 2: DIAGNOSIS, INTERVENTION, AND HUMAN BODY TERMS 28 LESSON 3: MUSCULOSKELETAL, CIRCULATORY, AND RESPIRATORY SYSTEM TERMS 44 LESSON 4: DIGESTIVE, URINARY, AND REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM TERMS 69 LESSON 5: INTEGUMENTARY, NERVOUS, AND ENDOCRINE S YSTEM TERMS 96 SELF-CHECK ANSWERS 134 © PENN FOSTER, INC. 2017 MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY PAGE III Contents INSTRUCTIONS INTRODUCTION Welcome to your course on medical terminology. You’re taking this course because you’re most likely interested in pursuing a health and science career, which entails proficiencyincommunicatingwithhealthcareprofessionalssuchasphysicians,nurses, or dentists.