Kentucky River Development in 1917, the Steamboat Commerce It Was Designed to Support Came to an Abrupt End

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Topography Along the Virginia-Kentucky Border

Preface: Topography along the Virginia-Kentucky border. It took a long time for the Appalachian Mountain range to attain its present appearance, but no one was counting. Outcrops found at the base of Pine Mountain are Devonian rock, dating back 400 million years. But the rocks picked off the ground around Lexington, Kentucky, are even older; this limestone is from the Cambrian period, about 600 million years old. It is the same type and age rock found near the bottom of the Grand Canyon in Colorado. Of course, a mountain range is not created in a year or two. It took them about 400 years to obtain their character, and the Appalachian range has a lot of character. Geologists tell us this range extends from Alabama into Canada, and separates the plains of the eastern seaboard from the low-lying valleys of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. Some subdivide the Appalachians into the Piedmont Province, the Blue Ridge, the Valley and Ridge area, and the Appalachian plateau. We also learn that during the Paleozoic era, the site of this mountain range was nothing more than a shallow sea; but during this time, as sediments built up, and the bottom of the sea sank. The hinge line between the area sinking, and the area being uplifted seems to have shifted gradually westward. At the end of the Paleozoric era, the earth movement are said to have reversed, at which time the horizontal layers of the rock were uplifted and folded, and for the next 200 million years the land was eroded, which provided material to cover the surrounding areas, including the coastal plain. -

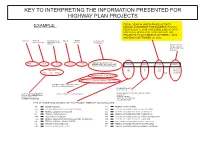

Key to Interpreting the Information Presented for Highway Plan Projects

KEY TO INTERPRETING THE INFORMATION PRESENTED FOR HIGHWAY PLAN PROJECTS FISCAL YEAR IN WHICH PHASE ACTIVITY EXAMPLE: SHOULD COMMENCE. FOR EXAMPLE, FY-2019 BEGINS JULY 1, 2018 AND ENDS JUNE 30, 2019 FOR STATE PROJECTS. FOR. FEDERAL-AID PROJECTS, FY 2019 BEGINS OCTOBER 1, 2018 AND ENDS SEPTEMBER 30, 2019. COUNTY YEAR OF KYTC PROJECT ROUTE LENGTH DESCRIPTION SIX-YEAR PLAN IDENTIFICA TION (MILES) OF PROJECT NUMBER PHASE COST OR TOTAL COST IN SCHEDULED YEAR DOLLARS ADDRESS DEFICIENCIES OF ADAIR 2018 08 - 1068.00 KY-704 0.008 BRIDGE ON KY 704 (11.909) OVER FUNDING PHASE YEAR AMOUNT PETTY'S FORK (001B00078N)(SD) BR D 2019 $175,000 Parent No.: BR C 2020 $490,000 2018 08 - 1068.00 Total $665,000 Milepoints: Fr om: 11.905 T o: 11.913 Purpose and Need: ASSET MANAGEMENT / AM-BRIDGE (P) BEGINNING AND ENDING MILEPOINTS (State Primary Roadway System) STAGE OF PROJECT DEVELOPMENT YEAR OF SIX-YEAR HIGHW AY TYPE OF PRIORITY / TYPE OF WORK P=PRELIMINAR Y ENG./EARLY PUBLIC COORD. PLAN & ITEM NUMBER FROM D=DESIGN WHICH ABOVE ITEM R=RIGHT OF WAY NUMBER WAS DERIVED. U=UTILITY RELOCATION C=CONSTRUCTION TYPE OF FUNDS TO BE UTILIZED FOR THE PROJECT, ABBREVIA TED AS FOLLOWS: BR BRIDGE PROGRAM SAF FEDERAL HIGHWAY SAFETY BR2 JP2 BRAC BOND PROJECTS SECOND PROGRAM SHN FEDERAL STP FUNDS DEDICATED TO HENDERSON CM FEDERAL CONGESTION MITIGATION SLO FEDERAL STP FUNDS DEDICATED TO LOUISVILLE FH FEDERAL FOREST HIGHW AY SLX FEDERAL STP FUNDS DEDICATED TO LEXINGT ON HPP HIGH PRIORITY PROJECTS SNK FEDERAL STP FUNDS DEDICATED TO NORTHERN KENTUCKY KYD FEDERAL DEMONSTRATION FUNDS ALLOCATED TO KENTUCKY SAH FEDERAL STP FUNDS DEDICATED TO ASHLAND NH FEDERAL NATIONAL HIGHW AY SYSTEM SPP STATE CONSTRUCTION HIGH PRIORITY PROJECTS PM PREVENTATIVE MAINTENANCE STP FEDERAL STATEWIDE TRANSPORTATION PROGRAM RRP SAFETY-RAILROAD PROTECTION TE FEDERAL TRANSPORTATION ENHANCEMENT PROGRAM KENTUCKY TRANSPORTATION CABINET Page: 1 SIX YEAR HIGHWAY PLAN 28 JUN 2018 FY - 2018 THRU FY - 2024 COUNTY ITEM NO. -

Family Fun in Lexington, KY

IIDEA GGUIDE FAMILY FUN Here Are a Few Dozen Ways to Make Anyone Feel Like a Kid Again Lexington Visitors Center 215 West Main Street Lexington, KY 40507 (859) 233-7299 or (800) 845-3959 www.visitlex.com Whoever said, “There are two types of travel, Thoroughbreds are so realistic they have first-class and with children,” obviously hadn’t supposedly even spooked real horses. Parents can been to Lexington. With unique horse and historic relax and let the youngsters pet, touch and even attractions as well as some unusual twists on family climb aboard – the statues are bronze, so they’re classics, the Bluegrass offers first-rate fun for very hardy (and don’t kick or bite)! This is a visitors of all ages. favorite photo location. You can’t miss this park at the corner of Midland and Main Street. Get the saddle’s-eye view. Several area stables Horsing Around offer scenic guided or unguided horseback rides for Explore a big park for horse-lovers. all levels of riders, including pony rides for younger Lexington’s Kentucky Horse Park is a great children. Big Red Stables in Harrodsburg attraction for all ages. Youngsters especially enjoy (859-734-3118) and Deer Run Stables in Madison the interactive exhibits at the museum, a parade of County (615-268-9960) are open year round, breeds called “Breeds Barn Show” (daily, spring weather permitting; and Whispering Woods in through fall at 11 a.m. and 2 p.m.) and the Scott County (502-570-9663) operates March wide-open spaces. The holiday light show at the through November. -

This Region, Centered Around Lexington, Is Known for Its Bluegrass. However, Bluegrass Is Not Really Blue — It's Green

N O I G E R S S A R G E U L B This region, centered around Lexington, is known for its bluegrass. However, bluegrass is not really blue — it’s green. In the spring, bluegrass produces bluish-purple buds that when seen in large fields give a rich blue cast to the grass. Today those large “bluegrass” fields are home to some of the best known horse farms in the world. With more than 500 horse farms in and around Lexington, the area is known as the Horse Capital of the World. PHOTO: HORSE FARM, LEXINGTON BEREA/RICHMOND AREA BEREA TOURIST COMMISSION 800-598-5263, www.berea.com RICHMOND TOURISM COMMISSION 800-866-3705, www.richmond-ky.com ACRES OF LAND WINERY Tour the winery & vineyards. Restaurant features many items raised on the farm. ; 2285 Barnes Mill Rd., Richmond 859-328-3000, 866-714-WINE www.acresoflandwinery.com BATTLE OF RICHMOND DRIVING TOUR A part of the National Trust Civil War Discovery Trail. 345 Lancaster Ave., Richmond 859-626-8474, 800-866-3705 N BEREA COLLEGE STUDENT CRAFT WALKING O I G TOURS b E R 2209 Main St., Berea, 859-985-3018, 800-347-3892 S S A R BEREA – KENTUCKY CRAFTS CAPITAL Home to a G E variety of working artists’ studios, galleries, antiques U L B and other specialty shops located in Old Town, College Square and the Chestnut Street area. 800-598-5263, 859-986-2540, www.berea.com DANIEL BOONE MONUMENT On EKU’s campus. University Dr., Richmond 859-622-1000, 800-465-9191, www.eku.edu DEER RUN STABLES, LLC Trail rides, pony rides, hayrides, bonfires, picnics, and rustic camping. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 111 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 111 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 155 WASHINGTON, MONDAY, JANUARY 12, 2009 No. 6 House of Representatives The House was not in session today. Its next meeting will be held on Tuesday, January 13, 2009, at 12:30 p.m. Senate MONDAY, JANUARY 12, 2009 The Senate met at 2 p.m. and was The legislative clerk read the fol- was represented in the Senate of the called to order by the Honorable JIM lowing letter: United States by a terrific man and a WEBB, a Senator from the Common- U.S. SENATE, great legislator, Wendell Ford. wealth of Virginia. PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE, Senator Ford was known by all as a Washington, DC, January 12, 2009. moderate, deeply respected by both PRAYER To the Senate: sides of the aisle for putting progress The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- Under the provisions of rule I, paragraph 3, ahead of politics. Senator Ford, some of the Standing Rules of the Senate, I hereby fered the following prayer: appoint the Honorable JIM WEBB, a Senator said, was not flashy. He did not seek Let us pray. from the Commonwealth of Virginia, to per- the limelight. He was quietly effective Almighty God, from whom, through form the duties of the Chair. and calmly deliberative. whom, and to whom all things exist, ROBERT C. BYRD, In 1991, Senator Ford was elected by shower Your blessings upon our Sen- President pro tempore. his colleagues to serve as Democratic ators. -

Oxford Proudly Supports the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra

Oxford proudly supports the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra. Enjoying your granddaughter’s ballet An Exceptional Everyday Experience It’s the little things in life that bring the most joy. At Twin Towers and Twin Lakes senior living communities, each day is filled with the wonderful things that make life sweeter – an entertaining show, delicious food, seeing your grandkids’ smiling faces. Find magic in the everyday. Call us to schedule a tour or visit us online at LEC.org. Oxford is independent and unbiased — and always will be. We are committed to providing families generational estate planning advice and institutions forward-thinking investment strategies. Twin Towers Twin Lakes 513.853.2000 513.247.1300 5343 Hamilton Avenue 9840 Montgomery Road Cincinnati, OH 45224 Cincinnati, OH 45242 Life Enriching Communities is affiliated with the West Ohio Conference CHICAGO ✦ CINCINNATI ✦ GRAND RAPIDS ✦ INDIANAPOLIS ✦ TWIN CITIES of the United Methodist Church and welcomes people of all faiths. 513.246.0800 ✦ WWW.OFGLTD.COM/CSO Oxford proudly supports the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra. Enjoying your granddaughter’s ballet An Exceptional Everyday Experience It’s the little things in life that bring the most joy. At Twin Towers and Twin Lakes senior living communities, each day is filled with the wonderful things that make life sweeter – an entertaining show, delicious food, seeing your grandkids’ smiling faces. Find magic in the everyday. Call us to schedule a tour or visit us online at LEC.org. Oxford is independent and unbiased — and always will be. We are committed to providing families generational estate planning advice and institutions forward-thinking investment strategies. -

Results of Investigations of Surface-Water Quality, 1987-90

WATER-QUALITY ASSESSMENT OF THE KENTUCKY RIVER BASIN, KENTUCKY: RESULTS OF INVESTIGATIONS OF SURFACE-WATER QUALITY, 1987-90 By Kirn H. Haag, Rene Garcia, G. Lynn Jarrett, and Stephen D. Porter U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 95-4163 Louisville, Kentucky . 1995 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Gordon P. Eaton, Director For additional information write to: Copies of this report can be purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Earth Science Information Center District Office Open-File Reports Section 2301 Bradley Avenue Box 25286, MS 517 Louisville, KY 40217 Denver Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 FOREWORD The mission of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) is to assess the quantity and quality of the earth resources of the Nation and to provide information that will assist resource managers and policymakers at Federal, State, and local levels in making sound decisions. Assessment of water-quality conditions and trends is an important part of this overall mission. One of the greatest challenges faced by water-resources scientists is acquiring reliable information that will guide the use and protection of the Nation's water resources. That challenge is being addressed by Federal, State, interstate, and local water-resource agencies and by many academic institutions. These organizations are collecting water-quality data for a host of purposes that include: compliance with permits and water-supply standards; development of remediation plans for a specific contamination problem; operational decisions on industrial, wastewater, or water-supply facilities; and research on factors that affect water quality. -

Fall 2010 a Publication of the Kentucky Native Plant Society [email protected]

The Lady-Slipper Number 25:3 Fall 2010 A Publication of the Kentucky Native Plant Society www.knps.org [email protected] Announcing the KNPS Fall Meeting at Shakertown Saturday, September 11, 2010 Plans are underway to for the KNPS Fall meeting at Mercer County’s Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill (http://www.shakervillageky.org/ )! Preliminary plans are for several field trips on Saturday morning and Saturday afternoon in the Kentucky River palisades region, followed by an afternoon program indoors. Details will be posted to www.KNPS.org as they are finalized, but here is our tentative schedule (all hikes subject to change): 9 AM field trips (meet at the West Family Wash House, area "C", in the main village): Don Pelly, Shakertown Naturalist- birding hike to Shakertown’s native grass plantings. David Taylor, US Forest Service- woody plant walk on the Shaker Village grounds. Zeb Weese, KNPS- Kentucky River canoe trip (limit 14 adults). Palisades from www.shakervillage.org 1 PM field trips (meet at the West Family Wash House): Tara Littlefield, KY State Nature Preserves– field trip to Jessamine Creek Gorge (limit 3 vehicles) Alan Nations, NativeScapes, Inc, - hike on the Shaker Village grounds. Sarah Hall, Kentucky State University- hike to Tom Dorman State Nature Preserve. 5 PM presentations at the West Family Wash House: Dr. Luke Dodd, UK Forestry, will present “Impacts of forest management on foraging bats in hardwood forests” followed by Greg Abernathy, KY State Nature Preserves Commission, on “Biodiversity of Kentucky” Registration will take place in the West Family Wash House prior to each field trip. -

Divide and Dissent: Kentucky Politics, 1930-1963

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Political History History 1987 Divide and Dissent: Kentucky Politics, 1930-1963 John Ed Pearce Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Pearce, John Ed, "Divide and Dissent: Kentucky Politics, 1930-1963" (1987). Political History. 3. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_political_history/3 Divide and Dissent This page intentionally left blank DIVIDE AND DISSENT KENTUCKY POLITICS 1930-1963 JOHN ED PEARCE THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 1987 by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2006 The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University,Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Qffices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pearce,John Ed. Divide and dissent. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Kentucky-Politics and government-1865-1950. -

Water-Quality Assessment of the Kentucky River Basin, Kentucky: Nutrients, Sediments, and Pesticides in Streams, 1987-90

WATER-QUALITY ASSESSMENT OF THE KENTUCKY RIVER BASIN, KENTUCKY: NUTRIENTS, SEDIMENTS, AND PESTICIDES IN STREAMS, 1987-90 By Kirn H. Haag and Stephen D. Porter U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 94-4227 Louisville, Kentucky 1995 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Gordon P. Eaton, Director For additional information write to: Copies of this report can be purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Earth Science Information Center District Office Open-File Reports Section 2301 Bradley Avenue Box 25286, MS 517 Louisville, KY 40217 Denver Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 CONTENTS Page Abstract................................................................ 1 Introduction............................................................ 2 Purpose and scope.................................................. 3 Surface-water-quality issues in the Kentucky River Basin........... 4 Acknowledgments.................................................... 5 Description of the Kentucky River Basin................................. 5 Physiography and topography........................................ 7 Climate and hydrology.............................................. 7 Population and land use............................................ 9 Water use.......................................................... 14 Constituent sources and effects on surface-water quality................ 14 Nutrients.......................................................... 14 Sediments......................................................... -

SC 379 KENTUCKY Anniversary 175Th.Pdf

bOVEKNOR EUWAKD T. BUEATHITT REDEDICATION OF JOHN BREATHITT MARKER SEPTEMBER 16, 1967 RUSSELLVILLE, KENTUCKY For Release at 10 a.m. I accepted with pleasure your Invitation to be here today for this part of Western Kentucky's observance of the Commonwealth's 175th anniversary. After all, I have a bit of kinship tie with the Kentucky ° statesman whose marker we rededlcate today. And by my Hopklnsvllle background, I have a geographic tie with this part of the state. Logan County Is celebrating its 175th anniversary, too. You Logan Countlans live In an area that became a county on September 1, 17tf2, just three months after the new Commonwealth of * Kentucky became a state. Most of you know that Logan County is the mother of some 20 counties. In fact, In the period of Kentucky statehood, Logan County then Included all of what Is now regarded as l^estern Kentucky except for the Jackson Purchase. And this county, as you also know, was named for General Benjamin Logan, who founded Logan's Station In 1775. He also was a member of the convention which wrote the first constitution for Kentucky and also a member of the Constitutional Convention of 1779. This Is another reason for the ceremonies here and at Fairview today -- honoring some of the most illustrious names In I- ^ -2- Kentucky's history -- and also serving as Western Kentucky's participa tion in the 175th Anniversary Year. The county seat of Logan County, when established, was known as Logan Court House. Logan County then Included all of the land bounded on the nortn by the Ohio River, on the south by the Tennessee River and west to ttte same river and east to Stanford in Central Kentucky. -

Rural Communities

BROADCAST TELEVISION AND RADIO IN Rural Communities More than other demographics, rural communities within the United States continue to rely on free and local broadcast stations. Through broadcast stations, Americans in rural communities receive their news, weather, sports and entertainment at a local level. As such, broadcast television and radio remain a vital and irreplaceable resource to rural individuals across the United States. Rural Population Across the U.S. Rural America accounts for 72 percent of the United States’ land area and 46.1 million people.1 Maine and Vermont are the most rural states, with nearly two-thirds of their populations living in rural areas. The southern region of the U.S. contains nearly one-half (46.7 percent) of the rural population, with 28 million people residing in rural areas in these states.2 Broadcast Television The number of broadcast-only households in the United States continues to rise, jumping nearly 16 percent from 2016 to 2017.3 More than 30 million American households, representing over 77 million individuals, receive television through over-the-air broadcast signals.4 Over-the-Air Television Penetration in Rural Areas Americans in small television markets that include rural areas depend on over-the-air broadcasting at greater levels than the general American population. The table below provides the percentage of households in 10 rural designated market areas (DMAs) that rely on free over-the-air television.5 Broadcast Only TV Homes in Small DMAs Fairbanks (DMA 202) Idaho Falls-Pocatello (DMA 162) Butte-Bozeman (DMA 185) Missoula (DMA 164) Grand Junction-Montrose (DMA 187) Helena (DMA 205) Twin Falls (DMA 190) Bend, OR (DMA 186) Casper-Riverton (DMA 198) 0% 5% 10% 15% 20% 25% 30% 35% 40% Source: Nielsen, October 2017 Over-the-air television provides immense local and informational program choice for rural and farming communities across the country.