The Construction of Macedonian National Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Draft Assessment Report: Skopje, North Macedonia

Highlights of the draft Assessment report for Skopje, North Macedonia General highlights about the informal/illegal constructions in North Macedonia The Republic of North Macedonia belongs to the European continent, located at the heart of the Balkan Peninsula. It has approx. 2.1 million inhabitants and are of 25.713 km2. Skopje is the capital city, with 506,926 inhabitants (according to 2002 count). The country consists of 80 local self-government units (municipalities) and the city of Skopje as special form of local self-government unit. The City of Skopje consists of 10 municipalities, as follows: 1. Municipality of Aerodrom, 2. Municipality of Butel, 3. Municipality of Gazi Baba, 4. Municipality of Gorche Petrov, 5. Municipality of Karpos, 6. Municipality of Kisela Voda, 7. Municipality of Saraj, 8. Municipality of Centar, 9. Municipality of Chair and 10. Municipality of Shuto Orizari. During the transition period, the Republic of North Macedonia faced challenges in different sectors. The urban development is one of the sectors that was directly affected from the informal/illegally constructed buildings. According to statistical data, in 2019 there was a registration of 886 illegally built objects. Most of these objects (98.4 %) are built on private land. Considering the challenge for the urban development of the country, in 2011 the Government proposed, and the Parliament adopted a Law on the treatment of unlawful constructions. This Law introduced a legalization process. Institutions in charge for implementation of the legalization procedure are the municipalities in the City of Skopje (depending on the territory where the object is constructed) and the Ministry of Transport and Communication. -

High Prevalence of Smoking in Northern Greece

Primary Care Respiratory Journal (2006) 15, 92—97 ORIGINAL RESEARCH High prevalence of smoking in Northern Greece Lazaros T. Sichletidis ∗, Diamantis Chloros, Ioannis Tsiotsios, Ioannis Kottakis, Ourania Kaiafa, Stella Kaouri, Alexandros Karamanlidis, Dimitrios Kalkanis, Sotirios Posporelis Pulmonary Clinic, Aristotle University of Thessalonica, and the Laboratory for the Investigation of Environmental Diseases, G. Papanicolaou General Hospital, Exochi, Thessalonica, 57010 Greece Received 23 April 2005; accepted 11 January 2006 KEYWORDS Summary Smoking; Aim: To investigate the prevalence of smoking in the general population and in Adolescent smoking; specific population sub-groups in Northern Greece. Teachers; Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted during the period 1999—2001 on Medical doctors; a 5% sample (23,840) of those people aged between 21 to 80 out of a total Epidemiology general population of 653,249. 21,854/23,840 general population subjects were interviewed. In addition, we interviewed 9,276 high school students, 1,072 medical students, 597 medical doctors within the National Health System, 825 teachers, and 624 subjects who regularly exercised in a privately-owned gym. A specially modified Copyright GeneralICRF study group questionnairePractice was used. Airways Group ReproductionResults: 34.4% of the general prohibited population sample were current smokers (47.8% of males and 21.6% of females). Smoking prevalence rates in the population sub-groups were: 29.6% of high school students; 40.7% of medical students; 44.9% of medical doctors; 46.4% of teachers; and 36.9% of the gym group. Conclusion: The prevalence of smoking in Northern Greece is high. High school and medical students present with high smoking rates, and the same situation is observed in medical doctors and teachers. -

The Statistical Battle for the Population of Greek Macedonia

XII. The Statistical Battle for the Population of Greek Macedonia by Iakovos D. Michailidis Most of the reports on Greece published by international organisations in the early 1990s spoke of the existence of 200,000 “Macedonians” in the northern part of the country. This “reasonable number”, in the words of the Greek section of the Minority Rights Group, heightened the confusion regarding the Macedonian Question and fuelled insecurity in Greece’s northern provinces.1 This in itself would be of minor importance if the authors of these reports had not insisted on citing statistics from the turn of the century to prove their points: mustering historical ethnological arguments inevitably strengthened the force of their own case and excited the interest of the historians. Tak- ing these reports as its starting-point, this present study will attempt an historical retrospective of the historiography of the early years of the century and a scientific tour d’horizon of the statistics – Greek, Slav and Western European – of that period, and thus endeavour to assess the accuracy of the arguments drawn from them. For Greece, the first three decades of the 20th century were a long period of tur- moil and change. Greek Macedonia at the end of the 1920s presented a totally different picture to that of the immediate post-Liberation period, just after the Balkan Wars. This was due on the one hand to the profound economic and social changes that followed its incorporation into Greece and on the other to the continual and extensive population shifts that marked that period. As has been noted, no fewer than 17 major population movements took place in Macedonia between 1913 and 1925.2 Of these, the most sig- nificant were the Greek-Bulgarian and the Greek-Turkish exchanges of population under the terms, respectively, of the 1919 Treaty of Neuilly and the 1923 Lausanne Convention. -

Royal Power, Law and Justice in Ancient Macedonia Joseph Roisman

Royal Power, Law and Justice in Ancient Macedonia Joseph Roisman In his speech On the Crown Demosthenes often lionizes himself by suggesting that his actions and policy required him to overcome insurmountable obstacles. Thus he contrasts Athens’ weakness around 346 B.C.E. with Macedonia’s strength, and Philip’s II unlimited power with the more constrained and cumbersome decision-making process at home, before asserting that in spite of these difficulties he succeeded in forging later a large Greek coalition to confront Philip in the battle of Chaeronea (Dem.18.234–37). [F]irst, he (Philip) ruled in his own person as full sovereign over subservient people, which is the most important factor of all in waging war . he was flush with money, and he did whatever he wished. He did not announce his intentions in official decrees, did not deliberate in public, was not hauled into the courts by sycophants, was not prosecuted for moving illegal proposals, was not accountable to anyone. In short, he was ruler, commander, in control of everything.1 For his depiction of Philip’s authority Demosthenes looks less to Macedonia than to Athens, because what makes the king powerful in his speech is his freedom from democratic checks. Nevertheless, his observations on the Macedonian royal power is more informative and helpful than Aristotle’s references to it in his Politics, though modern historians tend to privilege the philosopher for what he says or even does not say on the subject. Aristotle’s seldom mentions Macedonian kings, and when he does it is for limited, exemplary purposes, lumping them with other kings who came to power through benefaction and public service, or who were assassinated by men they had insulted.2 Moreover, according to Aristotle, the extreme of tyranny is distinguished from ideal kingship (pambasilea) by the fact that tyranny is a government that is not called to account. -

Carol Migdalovitz Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs Foreign Affairs, Trade, and Defense Division

Order Code RS21855 Updated October 16, 2007 Greece Update Carol Migdalovitz Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs Foreign Affairs, Trade, and Defense Division Summary The conservative New Democracy party won reelection in September 2007. Kostas Karamanlis, its leader, remained prime minister and pledged to continue free-market economic reforms to enhance growth and create jobs. The government’s foreign policy focuses on the European Union (EU), relations with Turkey, reunifying Cyprus, resolving a dispute with Macedonia over its name, other Balkan issues, and relations with the United States. Greece has assisted with the war on terrorism, but is not a member of the coalition in Iraq. This report will be updated if developments warrant. See also CRS Report RL33497, Cyprus: Status of U.N. Negotiations and Related Issues, by Carol Migdalovitz. Government and Politics Prime Minister Kostas Karamanlis called for early parliamentary elections to be held on September 16, 2007, instead of in March 2008 as otherwise scheduled, believing that his government’s economic record would ensure easy reelection. In August, however, Greece experienced severe and widespread wildfires, resulting in 76 deaths and 270,000 hectares burned. The government attempted to deflect attention from what was widely viewed as its ineffective performance in combating the fires by blaming the catastrophe on terrorists, without proof, and by providing generous compensation for victims. This crisis came on top of a scandal over the state pension fund’s purchase of government bonds at inflated prices. Under these circumstances, Karamanlis’s New Democracy party’s (ND) ability to win of a slim majority of 152 seats in the unicameral 300-seat parliament and four more years in office was viewed as a victory. -

The Macedonian “Name” Dispute: the Macedonian Question—Resolved?

Nationalities Papers (2020), 48: 2, 205–214 doi:10.1017/nps.2020.10 ANALYSIS OF CURRENT EVENTS The Macedonian “Name” Dispute: The Macedonian Question—Resolved? Matthew Nimetz* Former Personal Envoy of the Secretary-General of the United Nations and former Special Envoy of President Bill Clinton, New York, USA *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract The dispute between Greece and the newly formed state referred to as the “Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia” that emerged out of the collapse of Yugoslavia in 1991 was a major source of instability in the Western Balkans for more than 25 years. It was resolved through negotiations between Athens and Skopje, mediated by the United Nations, resulting in the Prespa (or Prespes) Agreement, which was signed on June 17, 2018, and ratified by both parliaments amid controversy in their countries. The underlying issues involved deeply held and differing views relating to national identity, history, and the future of the region, which were resolved through a change in the name of the new state and various agreements as to identity issues. The author, the United Nations mediator in the dispute for 20 years and previously the United States presidential envoy with reference to the dispute, describes the basis of the dispute, the positions of the parties, and the factors that led to a successful resolution. Keywords: Macedonia; Greece; North Macedonia; “Name” dispute The Macedonian “name” dispute was, to most outsiders who somehow were faced with trying to understand it, certainly one of the more unusual international confrontations. When the dispute was resolved through the Prespa Agreement between Greece and (now) the Republic of North Macedonia in June 2018, most outsiders (as frequently expressed to me, the United Nations mediator for 20 years) responded, “Why did it take you so long?” And yet, as protracted conflicts go, the Macedonian “name” dispute is instructive as to the types of issues that go to the heart of a people’s identity and a nation’s sense of security. -

Blood Ties: Religion, Violence, and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878

BLOOD TIES BLOOD TIES Religion, Violence, and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 I˙pek Yosmaog˘lu Cornell University Press Ithaca & London Copyright © 2014 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2014 by Cornell University Press First printing, Cornell Paperbacks, 2014 Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Yosmaog˘lu, I˙pek, author. Blood ties : religion, violence,. and the politics of nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 / Ipek K. Yosmaog˘lu. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8014-5226-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8014-7924-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Macedonia—History—1878–1912. 2. Nationalism—Macedonia—History. 3. Macedonian question. 4. Macedonia—Ethnic relations. 5. Ethnic conflict— Macedonia—History. 6. Political violence—Macedonia—History. I. Title. DR2215.Y67 2013 949.76′01—dc23 2013021661 Cornell University Press strives to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the fullest extent possible in the publishing of its books. Such materials include vegetable-based, low-VOC inks and acid-free papers that are recycled, totally chlorine-free, or partly composed of nonwood fibers. For further information, visit our website at www.cornellpress.cornell.edu. Cloth printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Paperback printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To Josh Contents Acknowledgments ix Note on Transliteration xiii Introduction 1 1. -

The Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization and the Idea for Autonomy for Macedonia and Adrianople Thrace

The Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization and the Idea for Autonomy for Macedonia and Adrianople Thrace, 1893-1912 By Martin Valkov Submitted to Central European University Department of History In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Prof. Tolga Esmer Second Reader: Prof. Roumen Daskalov CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2010 “Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author.” CEU eTD Collection ii Abstract The current thesis narrates an important episode of the history of South Eastern Europe, namely the history of the Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization and its demand for political autonomy within the Ottoman Empire. Far from being “ancient hatreds” the communal conflicts that emerged in Macedonia in this period were a result of the ongoing processes of nationalization among the different communities and the competing visions of their national projects. These conflicts were greatly influenced by inter-imperial rivalries on the Balkans and the combination of increasing interference of the Great European Powers and small Balkan states of the Ottoman domestic affairs. I argue that autonomy was a multidimensional concept covering various meanings white-washed later on into the clean narratives of nationalism and rebirth. -

Very Short History of the Macedonian People from Prehistory to the Present

Very Short History of the Macedonian People From Prehistory to the Present By Risto Stefov 1 Very Short History of the Macedonian People From Pre-History to the Present Published by: Risto Stefov Publications [email protected] Toronto, Canada All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief and documented quotations in a review. Copyright 2008 by Risto Stefov e-book edition 2 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................4 Pre-Historic Macedonia...............................................................................6 Ancient Macedonia......................................................................................8 Roman Macedonia.....................................................................................12 The Macedonians in India and Pakistan....................................................14 Rise of Christianity....................................................................................15 Byzantine Macedonia................................................................................17 Kiril and Metodi ........................................................................................19 Medieval Macedonia .................................................................................21 -

Wine Roads of Northern Greece: a Network Promoting Greek Cultural Heritage Related to Wine

Good practice: Wine roads of Northern Greece: a network promoting Greek cultural heritage related to wine Lamprini Tsoli Project MSc Engineering & Management partner Regional Development Fund of Central Macedonia logo on behalf of the Region of Central Macedonia 07 February 2019 / Webinar, Policy Learning Platform WINE ROADS OF NORTHERN GREECE A Network of wine producers (wineries) and local tourism businesses (hotels, restaurants) that aim to establish wine tourism in Northern Greece by promoting wine-making tradition and local wine products along with other cultural assets of the Northern Greece including tangible and intangible heritage (local cuisine, industrial architecture, folklore etc) MAIN GOALS OF GOOD PRACTICE: ➢ Achieve acknowledgment of the Greek Wines ➢ Reinforce Greek cultural heritage and local wine related activities ➢ Promote universal understanding of the wine making ➢ Put into practice an effective institutional and legal framework process regarding cultural routes ➢ Preserve the origins of varieties of Northern grapes ➢ Promote international cooperation with companies and and wines organizations for the promotion of wine tourism and the promotion of local wine products and grape varieties 2 INNOVATIVENESS/ ADVANTAGES INNOVATIVENESS ▪ Emerge and strengthen wine tourism in Greece ▪ Promote wine tourism along with cultural tourism ▪ Development of 8 thematic routes (including vineyards, wineries and other cultural heritage landmarks) ▪ Involvement of 32 wineries in Thessaly, Macedonia, Thrace and Epirus ADVANTAGES ▪ -

REGIONAL ACTION PLAN for the REGION of CENTRAL MACEDONIA –GREECE

REGIONAL ACTION PLAN for the REGION OF CENTRAL MACEDONIA –GREECE In the context of PURE COSMOS Project- Public Authorities Role Enhancing Competitiveness of SMEs March 2019 Development Agency of Eastern Thessaloniki’s Local Authorities- ANATOLIKI SA REGION OF CENTRAL MACEDONIA HELLENIC REPUBLIC Thessaloniki 19 /9/2019 REGION OF CENTRAL MACEDONIA, Prot. Number:. Oik.586311(1681) DIRECTORATE OF INNOVATION AND ENTREPRENEUSHIP SUPPORT Address :Vasilissis Olgas 198, PC :GR 54655, Thessaloniki, Greece Information : Mr Michailides Constantinos Telephone : +302313 319790 Email :[email protected] TO: Development Agency of Eastern Thessaloniki’s Local Authorities- ANATOLIKI SA SUBJECT: Approval of the REGIONAL ACTION PLAN for the REGION OF CENTRAL MACEDONIA –GREECE in the context of PURE COSMOS Project-“Public Authorities Role Enhancing Competitiveness of SMEs” Dear All With this letter we would like to confirm ñ that we were informed about the progress of the Pure Cosmos project throughout its phase 1, ñ that we were in regular contact with the project partner regarding the influence of the policy instrument and the elaboration of the action plan, ñ that the activities described in the action plan are in line with the priorities of the axis 1 of the ROP of Central Macedonia, ñ that we acknowledge its contribution to the expected results and impact on the ROP and specifically on the mechanism for supporting innovation and entrepreneurship of the Region of Central Macedonia, ñ that we will support the implementation of the Action Plan during -

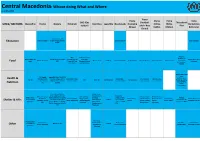

Central Macedonia: Whose Doing What and Where As of May 2016

Central Macedonia: Whose doing What and Where as of May 2016 Pieria Pieria Pieria Pieria Veria EKO (Gas (football Thessalonik Alexandria Cherso Diavata Eidomeni Giannitsa Lagadikia Nea Kavala (Camping (Ktima (Petra (Armatolou SITES/ SECTORS station) pitch- Nea i Port Nireas) Iraklis) Olybou) Kokkinou) Chrani) Humanity Crew, SOS Education Save the Children Children Villages; Save the Save the Children Veria Volunteers children Aristotele MSF, Lighthouse Refugee University of Hellenic Army; IRC Hellenic Army; IRC (cash); UNHCR,Samaritan's Relief, MSF, Hellenic Army ,Veria Hellenic Army; HRC Hellenic Army UNHCR Hellenic Army; HRC Hellenic Army Hellenic Air Force Hellenic Air Force Hellenic Army Thessaloniki, Food (cash) HRC Purse; HRC; Save Samaritan's Purse; Volunteers Hellenic Army , the children Save the children PRAKSIS Agape, Hellenic Red Cross, IFRC, Israaid, Agape,HRC,Mdm,PRAKSIS,SO MdM,National Health & PRAKSIS, WAHA, S Children Villages, WAHA; MSF; MDM; Praksis; IFRC,PRAKSIS, HRC, Voluntary HRC, Voluntary HRC; IRC MSF MDM; IRC UNHCR (MdM) HRC, Volunteers Health Operations Save the Children; MDM; Save the children; Save the children Save the Children Team of Action Team of Action Cener (EKEPY), Nutrition IRC IRC; IFRC WAHA, SolidarityNow Green Helmet, Hellenic Hellenic Army, Army, Lighthouse Refugee Evangelic church Drop in The Hellenic Army, Save MSF, Lighthouse Hellenic Air Force, Hellenic Air Force, Hellenic Army, Relief, Chef's Club - Ecopolis, of Greece, Ocean, Hellenic PRAKSIS, the Children, Terre des hommes, Refugee Relief,