<I>Halichoeres Cyanocephalus</I>

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

N Euroendocrine Control of Cleaning Behaviour in Labroides Dimidiatus (Labridae, Teleostei)

Symbiosis, 4 (1987) 259-274 259 Balaban Publishers, Philadelphia/Rehovot N euroendocrine Control of Cleaning Behaviour in Labroides dimidiatus (Labridae, Teleostei) ROLF LENKE Fachbereich Biologie der J. W. Goethe- Universitiit Theodor-Stern-Kai 7, Haus 74-III, D-6000 Frankfurt/Main, F.R.G. Tel. 49-69-6901-1 Received February 13, 1987; Accepted May 11, 1987 Abstract Cleaning symbiosis between Labroides dimidiatus and other saltwater fish is not dependent only on visual-tactile stimuli, since the cleaning motivation of the wrasse is strongly influenced by endogenous factors. The application of various neurohormones (neurotransmitters: 5-HT (5-HTP; PCPA), noradrenalin, L• Dopa; tissue hormone: VIP) as well as the opiate-antagonist naloxone, resulted in a change of the actual cleaning time, which possibly indicates the influence of many other interacting hormones of the fish's endocrine system. Keywords: Labroides dimidiatus, cleaning motivation, serotonin, 5-hydroxytrypto• phanparachloropheny lalanine, 3 ,4-dihydroxypheny lalanine, nor adrenalin, vasoacti ve-intestinal-polypeptide, naloxone 1. Introduction Cleaning symbiosis has been reported for many species, however, with- out considering the moods ( cleaning motivation) of the partners involved. Up until now, more than 40 species of fish have been described to be ac• tive in cleaning, where either juvenile, or juvenile and adult animals of one species (obligatory cleaners) inspect strange fish (Brockmann and Hailman, 1976; Matthes, 1978). While interspecific relations among freshwater fish are hardly known (Abel, 1971), several marine teleosts demonstrate a highly rit• ualized behavioural program with special sign stimuli, and, as far as tropical species are concerned, are found at characteristic points of the reef ( cleaning 260 R. -

Reef Fishes of the Bird's Head Peninsula, West

Check List 5(3): 587–628, 2009. ISSN: 1809-127X LISTS OF SPECIES Reef fishes of the Bird’s Head Peninsula, West Papua, Indonesia Gerald R. Allen 1 Mark V. Erdmann 2 1 Department of Aquatic Zoology, Western Australian Museum. Locked Bag 49, Welshpool DC, Perth, Western Australia 6986. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Conservation International Indonesia Marine Program. Jl. Dr. Muwardi No. 17, Renon, Denpasar 80235 Indonesia. Abstract A checklist of shallow (to 60 m depth) reef fishes is provided for the Bird’s Head Peninsula region of West Papua, Indonesia. The area, which occupies the extreme western end of New Guinea, contains the world’s most diverse assemblage of coral reef fishes. The current checklist, which includes both historical records and recent survey results, includes 1,511 species in 451 genera and 111 families. Respective species totals for the three main coral reef areas – Raja Ampat Islands, Fakfak-Kaimana coast, and Cenderawasih Bay – are 1320, 995, and 877. In addition to its extraordinary species diversity, the region exhibits a remarkable level of endemism considering its relatively small area. A total of 26 species in 14 families are currently considered to be confined to the region. Introduction and finally a complex geologic past highlighted The region consisting of eastern Indonesia, East by shifting island arcs, oceanic plate collisions, Timor, Sabah, Philippines, Papua New Guinea, and widely fluctuating sea levels (Polhemus and the Solomon Islands is the global centre of 2007). reef fish diversity (Allen 2008). Approximately 2,460 species or 60 percent of the entire reef fish The Bird’s Head Peninsula and surrounding fauna of the Indo-West Pacific inhabits this waters has attracted the attention of naturalists and region, which is commonly referred to as the scientists ever since it was first visited by Coral Triangle (CT). -

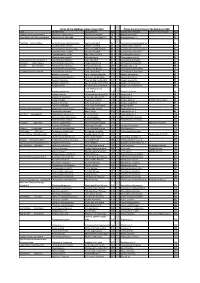

APPENDIX 1 Classified List of Fishes Mentioned in the Text, with Scientific and Common Names

APPENDIX 1 Classified list of fishes mentioned in the text, with scientific and common names. ___________________________________________________________ Scientific names and classification are from Nelson (1994). Families are listed in the same order as in Nelson (1994), with species names following in alphabetical order. The common names of British fishes mostly follow Wheeler (1978). Common names of foreign fishes are taken from Froese & Pauly (2002). Species in square brackets are referred to in the text but are not found in British waters. Fishes restricted to fresh water are shown in bold type. Fishes ranging from fresh water through brackish water to the sea are underlined; this category includes diadromous fishes that regularly migrate between marine and freshwater environments, spawning either in the sea (catadromous fishes) or in fresh water (anadromous fishes). Not indicated are marine or freshwater fishes that occasionally venture into brackish water. Superclass Agnatha (jawless fishes) Class Myxini (hagfishes)1 Order Myxiniformes Family Myxinidae Myxine glutinosa, hagfish Class Cephalaspidomorphi (lampreys)1 Order Petromyzontiformes Family Petromyzontidae [Ichthyomyzon bdellium, Ohio lamprey] Lampetra fluviatilis, lampern, river lamprey Lampetra planeri, brook lamprey [Lampetra tridentata, Pacific lamprey] Lethenteron camtschaticum, Arctic lamprey] [Lethenteron zanandreai, Po brook lamprey] Petromyzon marinus, lamprey Superclass Gnathostomata (fishes with jaws) Grade Chondrichthiomorphi Class Chondrichthyes (cartilaginous -

Halichoeres Bivittatus (Bloch, 1791) Frequent Synonyms / Misidentifications: None / Halichoeres Maculipinna (Müller and Troschel, 1848)

click for previous page 1710 Bony Fishes Halichoeres bivittatus (Bloch, 1791) Frequent synonyms / misidentifications: None / Halichoeres maculipinna (Müller and Troschel, 1848). FAO names: En - Slippery dick. Diagnostic characters: Body slender, depth 3.3 to 4.6 in standard length.Head rounded and scaleless;snout blunt; 1 pair of enlarged canine teeth at front of upper jaw and a small canine posteriorly near corner of mouth; 2 pairs of enlarged canine teeth anteriorly in lower jaw. Gill rakers on first arch 16 to 19. Dorsal fin continu- ous, with 9 spines and 11 soft rays;anal fin with 3 spines and 9 soft rays;caudal fin rounded;pectoral-fin rays 13. Lateral line continuous with an abrupt downward bend beneath soft portion of dorsal fin, and 27 pored scales. Colour: body colour variable, primarily pale green to white ground colour with a dark midbody stripe, a second lower stripe often present but less distinct; small green and yellow bicoloured spot above pectoral fin; pinkish or orange markings on the head, these sometimes outlined with pale blue; in adults, the tips of the cau- dal-fin lobes are black. Size: Maximum length to about 20 cm. Habitat, biology, and fisheries: Inhabits a di- versity of habitats from coral reef to rocky reef and seagrass beds. Any disturbance of the bot- tom, such as the overturning of a rock will attract a swarm of them, all hoping to find food uncov- ered. Feeds omnivorously on crabs, fishes, sea urchins, polychaetes, molluscs, and brittle stars. This species is not marketed for food, but is com- monly seen in the aquarium trade. -

The Marine Biodiversity and Fisheries Catches of the Pitcairn Island Group

The Marine Biodiversity and Fisheries Catches of the Pitcairn Island Group THE MARINE BIODIVERSITY AND FISHERIES CATCHES OF THE PITCAIRN ISLAND GROUP M.L.D. Palomares, D. Chaitanya, S. Harper, D. Zeller and D. Pauly A report prepared for the Global Ocean Legacy project of the Pew Environment Group by the Sea Around Us Project Fisheries Centre The University of British Columbia 2202 Main Mall Vancouver, BC, Canada, V6T 1Z4 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD ................................................................................................................................................. 2 Daniel Pauly RECONSTRUCTION OF TOTAL MARINE FISHERIES CATCHES FOR THE PITCAIRN ISLANDS (1950-2009) ...................................................................................... 3 Devraj Chaitanya, Sarah Harper and Dirk Zeller DOCUMENTING THE MARINE BIODIVERSITY OF THE PITCAIRN ISLANDS THROUGH FISHBASE AND SEALIFEBASE ..................................................................................... 10 Maria Lourdes D. Palomares, Patricia M. Sorongon, Marianne Pan, Jennifer C. Espedido, Lealde U. Pacres, Arlene Chon and Ace Amarga APPENDICES ............................................................................................................................................... 23 APPENDIX 1: FAO AND RECONSTRUCTED CATCH DATA ......................................................................................... 23 APPENDIX 2: TOTAL RECONSTRUCTED CATCH BY MAJOR TAXA ............................................................................ -

Download the Full List of Species Name Changes For

Fishes of the Maldives Indian Ocean 2014 Photo Guide to Fishes of the Maldives 1998 Family Scientific Name Common Name Page Scientific Name Changed Common Name Changed Page Solderfishes Holocentridae-2 Myripristis melanosticta Splendid Soldierfish 78 Myripristis botche 47 Ghost Pipefishes Solenostomidae Solenostomus halimeda Coralline Ghost Pipefish 81 Solenostome sp. 1 50 Pipefishes Syngnathidae Corythoichthys haematopterus Reef-top Pipefish 82 Corythoichtys haematopterus* 51 Corythoichthys schultzi Schultz’s Pipefish 83 Corythoichtys schultzi* 51 Corythoichthys flavofasciatus Yellow-banded Pipefish 83 Corythoichtys flavofasciatus* 51 Corythoichthys insularis Cheeked Pipefish 83 Corythoichtys insularis* 51 Doryrhamphus excisus Blue-stripe Pipefish 84 Doryrhamphus exicus* 53 Hippocampus jayakari Spiny Seahorse 85 Hippocampus hystrix 53 Scorpionfishes Scorpaenidae-2 Scorpaenopsis diabolus False Stonefish 89 Scorpaenopsis diabola 57 Groupers Serranidae-2 Cephalopholis leopardus Leopard Rock Cod 98 Cephalopholis leoparda 66 Basslets Serranidae-3 Pseudanthias lunulatus Yellow-eye Basslet 107 Pseudanthias n. sp. 74 Pseudanthias bimarginatus Short-snout Basslet 109 Pseudanthias parvirostris 76 Cardinalfishes Apogonidae Cheilodipterus lineatus Tiger Cardinalfish 114 Cheilodipterus macrodon 81 Apogon urostigma Spiny-head Cardinalfish 117 Apogon kallopterus 83 Apogon melanorhynchus Spiny-eye Cardinalfish 117 Apogon fraenatus 84 Apogon fraenatus Tapered-line Cardinalfish 117 Apogon exostigma 84 Apogon savayensis Big-eye Dusky-cardinalfish 118 Apogon -

Fishery Conservation and Management Pt. 622, App. A

Fishery Conservation and Management Pt. 622, App. A vessel's unsorted catch of Gulf reef to complete prohibition), and seasonal fish: or area closures. (1) The requirement for a valid com- (g) South Atlantic golden crab. MSY, mercial vessel permit for Gulf reef fish ABC, TAC, quotas (including quotas in order to sell Gulf reef fish. equal to zero), trip limits, minimum (2) Minimum size limits for Gulf reef sizes, gear regulations and restrictions, fish. permit requirements, seasonal or area (3) Bag limits for Gulf reef fish. closures, time frame for recovery of (4) The prohibition on sale of Gulf golden crab if overfished, fishing year reef fish after a quota closure. (adjustment not to exceed 2 months), (b) Other provisions of this part not- observer requirements, and authority withstanding, a dealer in a Gulf state for the RD to close the fishery when a is exempt from the requirement for a quota is reached or is projected to be dealer permit for Gulf reef fish to re- reached. ceive Gulf reef fish harvested from the (h) South Atlantic shrimp. Certified Gulf EEZ by a vessel in the Gulf BRDs and BRD specifications. groundfish trawl fishery. [61 FR 34934, July 3, 1996, as amended at 61 FR 43960, Aug. 27, 1996; 62 FR 13988, Mar. 25, § 622.48 Adjustment of management 1997; 62 FR 18539, Apr. 16, 1997] measures. In accordance with the framework APPENDIX A TO PART 622ÐSPECIES procedures of the applicable FMPs, the TABLES RD may establish or modify the follow- TABLE 1 OF APPENDIX A TO PART 622Ð ing management measures: CARIBBEAN CORAL REEF RESOURCES (a) Caribbean coral reef resources. -

Phylogenetics and Geography of Speciation in New World Halichoeres T Wrasses ⁎ Peter C

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 121 (2018) 35–45 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Phylogenetics and geography of speciation in New World Halichoeres T wrasses ⁎ Peter C. Wainwrighta, , Francesco Santinib, David R. Bellwoodc, D. Ross Robertsond, Luiz A. Rochae, Michael E. Alfarob a Department of Evolution and Ecology, University of California, Davis, One Shields Avenue, Davis, CA 95616, USA b University of California Los Angeles, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, 610 Charles E Young Drive South, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA c Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, James Cook University, Townsville, QLD, 4811, Australia d Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Balboa, Rep. de Panama, Unit 0948, APO AA 34002, USA e California Academy of Sciences, Section of Ichthyology, 55 Music Concourse Drive, San Francisco, CA 94118, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The New World Halichoeres comprises about 30 small to medium sized wrasse species that are prominent Labridae members of reef communities throughout the tropical Western Atlantic and Eastern Pacific. We conducted a New World Halichoeres phylogenetic analysis of this group and related lineages using new and previously published sequence data. We Western Atlantic estimated divergence times, evaluated the monophyly of this group, their relationship to other labrids, as well as Eastern Pacific the time-course and geography of speciation. These analyses show that all members of New World Halichoeres Phylogeny form a monophyletic group that includes Oxyjulis and Sagittalarva. New World Halichoeres is one of numerous Biogeography Speciation labrid groups that appear to have radiated rapidly about 32 Ma and form a large polytomy within the julidine wrasses. -

Chec List an Update to the List of Coral Reef Fishes from Koh Tao, Gulf Of

Check List 10(5): 1123–1133, 2014 © 2014 Check List and Authors Chec List ISSN 1809-127X (available at www.checklist.org.br) Journal of species lists and distribution An update to the list PECIES S Gulf of Thailand OF of coral reef fishes from Koh Tao, 1* 2 ISTS Patrick Scaps and Chad Scott L 1 Laboratoire de Biologie animale,[email protected] Université des Sciences et Technologies de Lille, 59 655 Villeneuve d’Ascq Cédex, France. 2 New Heaven Reef Conservation Program, 48 Moo 3, Koh Tao, Suratthani, Thailand, 84360. * Corresponding author: E-mail: ABSTRACT: (i.e., cryptic species or transient Twenty-one species are reported for the first time from Koh Tao (Turtle Island) in the Gulf of Thailand. TInformationhis and photographs were obtained from local scuba divers in order to censusAntennatus rare and Histrio), Ophichthyidae (genusspecies onlyCallechelys present), duringPlatycephalidae one season) (genus or not previouslyThysanophrys recorded), Plotosidae fish species (genus living Plotosus on or near) and coral Synanceiidae reefs from the(genera area. Inimicus is the and first Synanceia time that species belonging to the families AntennariidaePseudobalistes, (genera Balistidae; Cyclichthys, Diodontidae; Bolbometopon, Scaridae; and Hippocampus, ), and reef-fish genera of severalAntennatus families nummifer ( (Antennariidae), Pseudobalistes marginatus (Balistidae), Monacanthus chinensis (Monacanthidae),Syngnathidae), Callechelys among others,marmora haveta been(Ophichthyidae), recorded in KohThysnophrys Tao. Of the cf. 21 chiltonae species reported(Platycephalidae), for the first Bolbometopon time from muricatumKoh Tao, 7 (Scaridae) species ( and Synanceia cf. verrucosa (Synanceidae)) are new records for the species found in the present study. Gulf of Thailand. To date, 223 species of coral reef fishes belonging to 53 families are known from Koh Tao, including the 10.15560/10.5.1123 DOI: Introduction MaterialS and Methods 2 archipelago in the western Gulf of Thailand. -

Examples of Symbiosis in Tropical Marine Fishes

ARTICLE Examples of symbiosis in tropical marine fishes JOHN E. RANDALL Bishop Museum, 1525 Bernice St., Honolulu, HI 96817-2704, USA E-mail: [email protected] ARIK DIAMANT Department of Pathobiology, Israel Oceanographic and Limnological Research Institute National Center of Mariculture, Eilat, Israel 88112 E-mail: [email protected] Introduction The word symbiosis is from the Greek meaning “living together”, but present usage means two dissimilar organisms living together for mutual benefit. Ecologists prefer to use the term mutualism for this. The significance of symbiosis and its crucial role in coral reef function is becoming increasingly obvious in the world’s warming oceans. A coral colony consists of numerous coral polyps, each like a tiny sea anemone that secretes calcium carbonate to form the hard skeletal part of coral. The polyps succeed in developing into a coral colony only by forming a symbiotic relationship with a free-living yellowish brown algal cell that has two flagella for locomotion. These cells penetrate the coral tissue (the flagella drop off) to live in the inner layer of the coral polyps collectively as zooxanthellae and give the yellowish brown color to the coral colony. As plants, they use the carbon dioxide and water from the respiration of the polyps to carry out photosynthesis that provides oxygen, sugars, and lipids for the growth of the coral. All this takes place within a critical range of sea temperature. If too warm or too cold, the coral polyps extrude their zooxanthellae and become white (a phenomenon also termed “bleaching”). If the sea temperature soon returns to normal, the corals can be reinvaded by the zooxanthellae and survive. -

Patterns of Resource-Use and Competition for Mutualistic Partners Between Two Species of Obligate Cleaner fish

Coral Reefs (2012) 31:1149–1154 DOI 10.1007/s00338-012-0933-9 NOTE Patterns of resource-use and competition for mutualistic partners between two species of obligate cleaner fish T. C. Adam • S. S. Horii Received: 30 December 2011 / Accepted: 25 June 2012 / Published online: 12 July 2012 Ó Springer-Verlag 2012 Abstract Cleaner mutualisms on coral reefs, where spe- Introduction cialized fish remove parasites from many species of client fishes, have greatly increased our understanding of mutu- One of the best known mutualisms on coral reefs is alism, yet we know little about important interspecific between cleaner fish and the client fishes that visit cleaners interactions between cleaners. Here, we explore the for the removal of ectoparasites. Recent work on cleaners potential for competition between the cleaners Labroides has greatly increased the understanding of the maintenance dimidiatus and Labroides bicolor during two distinct life of cooperation in mutualisms when one or more partners stages. Previous work has demonstrated that in contrast to has the ability to cheat (e.g., Bshary and Grutter 2002, L. dimidiatus, which establish cleaning stations, adult 2006; Raihani et al. 2010; Oates et al. 2010a). In the case of L. bicolor rove over large areas, searching for clients. We cleaner mutualisms, cheating involves cleaners feeding on show that site-attached juvenile L. bicolor associate with client mucus or tissue instead of parasites (Bshary and different microhabitat than juvenile L. dimidiatus and that Grutter 2002). While several mechanisms have been L. bicolor specialize on a narrower range of species than identified that can prevent cheating, a central mechanism L. -

Shallow Water Records of Fish

Shallow water records of fish Collected from or observed at Howland Island from 1927-2002. Collected or compiled by Mundy et al. (2002). Scientific Name Common Name GINGLYMOSTOMATIDAE Nurse Sharks Nebrius ferrugineus nurse shark CARCHARHINIDAE Requiem Sharks Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos grey reef shark Carcharhinus melanopterus reef blacktip shark Galeocerdo cuvieri tiger shark HEMIGALEIDAE Weasel Sharks Triaenodon obesus reef whitetip shark SPHYRNIDAE Hammerhead Sharks Sphyrna lewini scalloped hammerhead shark DASYATIDAE Sand Rays Taeniura meyeni MYLIOBATIDIDAE Eagle Rays Aetobatus narinari spotted eagle ray MOBULIDAE Manta Rays Manta sp. manta MURAENIDAE Moray Eels Anarchias allardicei Allardice’s moray Anarchias cantonenesis Canton Island moray Echidna nebulosa snowflake moray Echidna polyzona barred moray Enchelycore pardalis Gymnomuraena zebra zebra moray Gymnothorax breedini Gymnothorax chilospilus Gymnothorax javanicus giant moray Gymnothorax flavimarginatus yellow-margined moray Gymnothorax marshallensis Marshall Island moray Gymnothorax meleagris white-mouth moray Gymnothorax picta peppered moray Gymnothorax rueppelliae yellow-headed moray Gymnothorax sp. Gymnothorax thyrsoideus Gymnothorax undulatus undulated moray Uropterygius sp. Uropterygius marmoratus marbled snake moray OPHICHTHIDAE Myrichthys maculosus spotted snake eel CONGRIDAE Conger Eel Conger sp. CHANIDAE Milkfish Chanos chanos milkfish SYNODONTIDAE Lizardfishes Synodus sp. HOLOCENTRIDAE Squirrelfishes Myripristis berndti bigscale soldierfish Sargocentron caudimaculatum