Afon Aman, Bynamman, Carmarthenshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BD22 Neath Port Talbot Unitary Development Plan

G White, Head of Planning, The Quays, Brunel Way, Baglan Energy Park, Neath, SA11 2GG. Foreword The Unitary Development Plan has been adopted following a lengthy and com- plex preparation. Its primary aims are delivering Sustainable Development and a better quality of life. Through its strategy and policies it will guide planning decisions across the County Borough area. Councillor David Lewis Cabinet Member with responsibility for the Unitary Development Plan. CONTENTS Page 1 PART 1 INTRODUCTION Introduction 1 Supporting Information 2 Supplementary Planning Guidance 2 Format of the Plan 3 The Community Plan and related Plans and Strategies 3 Description of the County Borough Area 5 Sustainability 6 The Regional and National Planning Context 8 2 THE VISION The Vision for Neath Port Talbot 11 The Vision for Individual Localities and Communities within 12 Neath Port Talbot Cwmgors 12 Ystalyfera 13 Pontardawe 13 Dulais Valley 14 Neath Valley 14 Neath 15 Upper Afan Valley 15 Lower Afan Valley 16 Port Talbot 16 3 THE STRATEGY Introduction 18 Settlement Strategy 18 Transport Strategy 19 Coastal Strategy 21 Rural Development Strategy 21 Welsh Language Strategy 21 Environment Strategy 21 4 OBJECTIVES The Objectives in terms of the individual Topic Chapters 23 Environment 23 Housing 24 Employment 25 Community and Social Impacts 26 Town Centres, Retail and Leisure 27 Transport 28 Recreation and Open Space 29 Infrastructure and Energy 29 Minerals 30 Waste 30 Resources 31 5 PART 1 POLICIES NUMBERS 1-29 32 6 SUSTAINABILITY APPRAISAL Sustainability -

Amman Valley Trail

PANTYFFYNNON amman valley trail Is as comnis consequia sit voluptaque lis acerupti asimaximpor aut harum rerum cus STATION SUSPENSION maximin cus et qui ipsam si te vel ius qui voloreh endion naturepe voluptio di non BRIDGE consequo con restist escipicat omnihit ut a volest, sa suntiosam, ear Address xxxxx, POstcode xxxxx, Address mountain road YNYS DAWELA FINISH garnant NATURE PARK A M M Y N A N BR L A NA M G M A folland road N wern-ddu road A474 RIVER AMMAN A474 G A R N A BLACK N AM T NT M A MOUNTAIN O N CENTRE START pontamman road P GLANAMMAN A474 ammanford Amman Valley Trail Explore a former mining valley in the shadow of the Brecon Beacons on a beautifully meandering cycle trail, winding 7 miles from the swiftly regenerating town of Ammanford to the characterful settlement of Brynamman beneath the imposing Black Mountain. Watch for buzzards and red kites soaring above, inhale the scent of wild garlic and wildflowers in spring, and relax to the murmur and gurgle of the River Amman as it gushes alongside the trail. This gentle car-free route is a popular family afternoon ride, with playgrounds on the way and refreshments at either end. Pantyffynnon Station Pontamman, half a mile east of the town centre. break. Across the river to the north is the site of Built alongside the Dynevor tinplate works, this Here the undulating track weaves between the old Palais de Danse, a cinema and dance hall venerable Grade II-listed station – dating from gnarly trees above the river, with the sound of the built in 1923. -

11Th WELSH ORCHID FESTIVAL 1St & 2Nd September 2018 to Be Held at the National Botanic Garden of Wales Llanarthne, Carmarthenshire, Wales SA32 8HN

The Post Your Local Community Magazine Over 4800 copies Number 271 August 2018 Published by PostDatum, 24 Stone Street, Llandovery, Carms SA20 0JP Tel: 01550 721225 THE ORCHID STUDY GROUP PRESENTS ITS 11TH WELSH ORCHID FESTIVAL 1ST & 2ND SEPTEMBER 2018 To be held at the National Botanic Garden of Wales Llanarthne, Carmarthenshire, Wales SA32 8HN The Welsh Orchid Festival welcomes the return of some Festival opening hours: Saturday: 10.00am – 6.00pm of your favourite orchid nurseries, as well as new traders Sunday: 10.00am – 4.00pm with a dazzling array of rare orchid species and hybrids Normal admission fees to the Garden apply. Entry into for sale, and some of their finest and most spectacular the Orchid Marquee, talks and demonstrations is free. blooms. For a full list of attendees and programme of talks, There will also be stalls selling carnivorous plants, visit the OSG website: www.orchidstudygroup.org.uk orchid companion plants, botanical paintings and other (which will be updated regularly), or telephone the works of art, as well as orchid and general plant books. Secretary on: 01269 498002. Regular talks and demonstrations on all aspects of For information on the National orchid cultivation for both beginner and experienced Botanic Garden of Wales, please visit grower will be held throughout the weekend, as well as their website: www.gardenofwales.org. a workshop on orchid micropropagation. uk or telephone: 01558 667149. FOR ALL YOUR LOCAL NEWS & BUSINESS SERVICES ALL ABOUT The Post COPY DATE for next issue: 15th August 2018 Next issue distributed: 30th August 2018 The Post Future Copy Dates October ....................................14th September November .....................................16th October December/January 2019 ..........16th November 07/18(3) Opinions expressed in The Post are not necessarily those of the publisher, editor or designer and the magazine is in no way liable for those opinions. -

1 ANTIQUARY SUBJECTS: 1984 – 2019 Compiled by Jill Davies by Place

ANTIQUARY SUBJECTS: 1984 – 2019 compiled by Jill Davies By place: LOCATION AUTHOR SUBJECT Aberglasney Joyner, Paul John Dyer 1995 Abergwili Davies, J D Bishop Lord George Murray 2001 Abergwili Jones, Anthea Bishop Yorke 1774 2002 Abergwili various Merlin's Hill 1988 Abergwili, Bryn Myrddin Wells, Terry Nature diary 2012 Abermarlais Turvey, Roger Jones family 1558, 1586 2018 Abermarlais Turvey, Roger Jones family 1588, 1604 2019 Aman Valley Mathews, Ioan Trade Unions 1996 Amman Valley Walters, Huw & Jones, Bill Emigrants to Texas 2001 Ammanford Walters, Huw Amanwy 1999 Ammanford Davies, Roy Dunkirk evacuation 2003 Ammanford/Glanaman Walters, Huw Emma Goldman 2003 Black Mountain Ward, Anthony Nant Gare valley settlement 1995 Brechfa Prytherch, J & R Abergolau Prytherchs 2004 Brechfa Rees, David Brechfa Forest 2001 Brechfa Rees, David Forest of Glyncothi 1995 Brechfa Morgan-Jones, D Morgan-Jones family 2006 Broad Oak Rees, David Cistercian grange, Llanfihangel Cilfargen 1992 Brynamman Beckley, Susan Amman Iron Company 1995 Brynamman Evans, Mike Llangadog road 1985 Brynamman Jones, Peter Chapels 2015 Burry Port Davis, Paul Lletyrychen 1998 Burry Port Bowen, Ray Mynydd Mawr railway 1996 1 Capel Isaac Baker-Jones Chapel/Thomas Williams 2003 Carmarthen Dale-Jones, Edna 19C families 1990 Carmarthen Lord, Peter Artisan Painters 1991 Carmarthen Dale-Jones, Edna Assembly Rooms, Coffee pot etc 2002 Carmarthen Dale-Jones, Edna Waterloo frieze 2015 Carmarthen James, Terry Bishop Ferrar 2005 Carmarthen Davies, John Book of Ordinances 1993 Carmarthen -

Gbmaps.Com UK Postcode

Field Compost Ltd Delivery Area Map KW17 John o-Groats Delivery Areas Scrabster Thurso KW17 Durness Melvich Port Nis KW14 Bettyhill National Pallet Delivery Tongue KW14 KW17 KW1 Wick KW16 KW13 KWKW15 Local Crane Lift Delivery KW12 Scourie ZE2 KW5 KW2 KW17 KW3 Lybster Altnaharra KW11 KW ZE Contact Us For Prices & Options Stornoway KW16 HS1 Kinbrace KW6 ZE1 HS2 Dunbeath KW17 IV27 KW7 HS Lochinver Inchnadamph KW8 Helmsdale HS3 Ledmore IV28 KW9 ZE3 Lairg Brora Oykel Bridge Golspie Tarbert / Tairbeart IV26 KW10 HS4 Ullapool Bonar Bridge IV25 Dornoch IV24 HS5 IV19 Tain IV20 Gairloch IV17 IV23 IV18 IV21 Lossiemouth Lochmaddy Alness Invergordon HSHS6 IV16 IV31 Cullen IV22 Cromarty Buckie AB44 Uig IV11 Portsoy Banff Fraserburgh Kinlochewe Elgin AB56 IV15 IV7 IV10 AB45 AB43 Achnasheen IV14 Forres IV30 IV32 Dingwall Fortrose Nairn IV IV8 IV9 HS7 IV36 Shieldaig IV6 Muir of Ord Keith Aberchirder Dunvegan IV1 Turriff IV51 Rothes AB55 Mintlaw Inverness Peterhead IV55 IV54 AB53 Portree IV12 AB38 AB42 IV5 Charlestown of Aberlour IV40 Lochcarron IV56 IV3 Huntly IV4 Dufftown HS8 AB54 AB41 PH26 IV52 IV53 Cannich Ellon Drynoch IV48 Oldmeldrum Kyle of Lochalsh Drumnadrochit Grantown-on-Spey AB52 IV2 IV47 IV41 Carrbridge AB51 AB37 Lochboisdale IV49 IV42 PH23 Inverurie Invermoriston IV13 PH24 Tomintoul AB AB23 IV43 Alford Kintore AB21 PH25 IV40 IV63 AB33 Dyce Aviemore IV44 AB36 AB22 AB24 AB16 Fort Augustus AB25 IV46 PH22 AB32 Aberdeen PH44 AB11 PH32 AB15 AB10 HS9 Ardvasar Invergarry PH35 AB14 AB13 IV45 PH41 Kingussie Castlebay Newtonmore Aboyne AB12 PH43 Ballater -

Exploring Welsh Speakers' Language Use in Their Daily Lives

Exploring Welsh speakers’ language use in their daily lives Beaufort contacts: Fiona McAllister / Adam Blunt [email protected] [email protected] Bangor University contact: Dr Cynog Prys [email protected] Client contacts: Carys Evans [email protected], Eilir Jones [email protected] Iwan Evans [email protected] July 2013 BBQ01260 CONTENTS 1. Executive summary ...................................................................................... 4 2. The situation, research objectives and research method ......................... 7 2.1 The situation ................................................................................................ 7 2.2 Research aims ......................................................................................... 9 2.3 Research method ..................................................................................... 9 2.4 Comparisons with research undertaken in 2005 and verbatim comments used in the report ............................................ 10 3. Main findings .............................................................................................. 11 4. An overview of Welsh speakers’ current behaviour and attitudes ........ 21 4.1 Levels of fluency in Welsh ...................................................................... 21 4.2 Media consumption and participation in online and general activities in Welsh and English .................................................. 22 4.3 Usage of Welsh in different settings ...................................................... -

Swansea Region

ASoloeErlcrv lElrtsnpul rol uollElcossv splou^au lned soq6nH uaqdels D -ir s t_ ?a ii I,. II I 1' a : a rii rBL n -. i ! i I ET .t) ? -+ I t ) I I I (, J*i I 0r0EuuEsrr eqt lo NOOTOHFti'c T$'rr!'I.snGME oqt ol ap!n9 v This booklel is published by the Associalion lor trial archaeology ol south-wesl and mid-Wales. lndustrial Archaeology in association with lhe lnlormation on lhese can be oblained lrom the Royal Commission on Ancient and Hislorical address given below. Detailed surveys, notes Monuments in Wales and the South Wesl Wales and illustrations ol these ieatures are either lndustrial Archaeology Sociely. lt was prepared housed in the Commission s pre-publication lor the annual conference of the AIA, held in records or in lhe National Monuments Record Swansea in 1988. lor Wales. The laller is a major archive lhat can be consulted, lree ol charge, during normal The AIA was established in 1973 lo promote working hours at the headquaners of the Royal lhe study ol industrial archaeology and encour- Commission on Ancaenl and Historical Monu- age improved slandards ol recording, re- ments in Wales. Edleston House, Oueen's search. conservalion and publication. lt aims lo Road, Aberyslwyth SY23 2HP; (a 0970- suppon individuals and groups involved in the 624381. study and recording ol past induslrial aclivily and the preservation ol industrial monuments; The SWWIAS was lormed an 1972 to sludy and to represent the interests of industrial archaeo' record lhe industraal hastory ol the western parl logy at a national leveli lo hold conlerences and ol lhe south Wales coaltield. -

New Inn House, Gwynfe, Llangadog SA199NS

New Inn House, Gwynfe, Llangadog SA199NS Offers in the region of £435,000 • EER 60 EIR 51 • Versatile 4 Bedroom Detached Country Residence With Self Contained Annexe • Leisure Area Comprises Indoor Heated Swimming Pool, Hot Tub & Wet Room John Francis is a trading name of Countrywide Estate Agents, an appointed representative of Countrywide Principal Services Limited, which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. We endeavour to make our sales details accurate and reliable but they should not be relied on as statements or representations of fact and they do not constitute any part of an offer or contract. The seller does not make any representation to give any warranty in relation to the property and we have no authority to do so on behalf of the seller. Any information given by us in these details or otherwise is given without responsibility on our part. Services, fittings and equipment referred to in the sales details have not been tested (unless otherwise stated) and no warranty can be given as to their condition. We strongly recommend that all the information which we provide about the property is verified by yourself or your advisers. Please contact us before viewing the property. If there is any point of particular importance to you we will be pleased to provide additional information or to make further enquiries. We will also confirm that the property remains available. This is particularly important if you are contemplating travelling some distance to view the property. HC/WJ/59139/300518 Ceramic tiled floor, single panel Double glazed sliding sash window radiator, 2 double panelled to front, single panel radiator. -

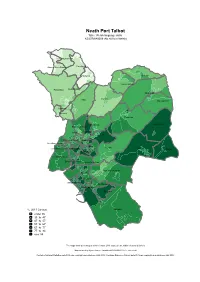

Neath Port Talbot Table: Welsh Language Skills KS207WA0009 (No Skills in Welsh)

Neath Port Talbot Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0009 (No skills in Welsh) Lower Brynamman Cwmllynfell Gwaun−Cae−Gurwen Ystalyfera Onllwyn Seven Sisters Pontardawe Godre'r graig Glynneath Rhos Crynant Blaengwrach Trebanos Allt−wen Resolven Aberdulais Glyncorrwg Bryn−coch North Dyffryn Cadoxton Tonna Bryn−coch South Neath North Coedffranc North Cimla Pelenna Cymmer Coedffranc Central Neath East Gwynfi Neath South Coedffranc West Briton Ferry West Briton Ferry East Bryn and Cwmavon Baglan Aberavon Sandfields West Port Talbot Sandfields East Tai−bach %, 2011 Census Margam under 35 35 to 47 47 to 57 57 to 67 67 to 77 77 to 84 over 84 The maps show percentages within Census 2011 output areas, within electoral divisions Map created by Hywel Jones. Variables KS208WA0022−27 corrected Contains National Statistics data © Crown copyright and database right 2013; Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2013 Neath Port Talbot Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0010 (Can understand spoken Welsh only) Lower Brynamman Gwaun−Cae−Gurwen Cwmllynfell Onllwyn Ystalyfera Seven Sisters Pontardawe Godre'r graig Glynneath Rhos Crynant Blaengwrach Allt−wen Trebanos Resolven Aberdulais Bryn−coch North Glyncorrwg Dyffryn Cadoxton Tonna Coedffranc North Bryn−coch South Neath North Coedffranc Central Neath South Pelenna Gwynfi Cimla Cymmer Neath East Briton Ferry West Coedffranc West Briton Ferry East Bryn and Cwmavon Baglan Sandfields West Aberavon Port Talbot Sandfields East Tai−bach %, 2011 Census Margam under 4 4 to 5 5 to 7 7 to 9 9 to 12 12 to 14 over 14 The maps show percentages within Census 2011 output areas, within electoral divisions Map created by Hywel Jones. -

47 Brynlloi Road, Glanamman, Ammanford, Dyfed, SA18 1EQ

01269 596659 www.westwalesproperties.co.uk 47 Brynlloi Road, Glanamman, Ammanford, Dyfed, SA18 1EQ **Village Location** An attractive terraced house, set in the village of Glanamman close to the local amenities and approximately 4 miles from the market town of Ammanford and with close links to the M4 and A48. This property comprises of entrance hall, lounge/diner, kitchen, and bathroom. First floor three bedrooms. Externally there is side access to the rear garden with parking for two cars, enclosed front garden, lower landscaped lawn. The garden looks out over open countryside with the mountain behind. Glanamman (Welsh Glanaman) is a Welsh village in the valley of the river Amman in Carmarthenshire. Like the neighboring village of Garnant, it experienced a coal-mining boom in the 19th and early 20th centuries, but the last big colliery closed in 1947 and coal has been extracted fitfully since then. Ammanford took its current name on the 20th of November 1880. The community that existed then and now known as Ammanford dates back to around the early 19th Century. The town is well served by local supermarkets, shops, resturants, chemists, Doctors and Leisure centre aswel as numerous primary schools and secondary schools offering education through the medium of Welsh and English. • Mid Terraced Property • Three Bedrooms • Lounge/Diner • Off Road Parking • Gas Central Heating • Village Location • Countryside Views • EPC Rating: E Price £104,950 COMPUTER-LINKED OFFICES THROUGHOUT WEST WALES and Associated Office in Mayfair, London 39 Quay -

NLCA39 Gower - Page 1 of 11

National Landscape Character 31/03/2014 NLCA39 GOWER © Crown copyright and database rights 2013 Ordnance Survey 100019741 Penrhyn G ŵyr – Disgrifiad cryno Mae Penrhyn G ŵyr yn ymestyn i’r môr o ymyl gorllewinol ardal drefol ehangach Abertawe. Golyga ei ddaeareg fod ynddo amrywiaeth ysblennydd o olygfeydd o fewn ardal gymharol fechan, o olygfeydd carreg galch Pen Pyrrod, Three Cliffs Bay ac Oxwich Bay yng nglannau’r de i halwyndiroedd a thwyni tywod y gogledd. Mae trumiau tywodfaen yn nodweddu asgwrn cefn y penrhyn, gan gynnwys y man uchaf, Cefn Bryn: a cheir yno diroedd comin eang. Canlyniad y golygfeydd eithriadol a’r traethau tywodlyd, euraidd wrth droed y clogwyni yw bod yr ardal yn denu ymwelwyr yn eu miloedd. Gall y priffyrdd fod yn brysur, wrth i bobl heidio at y traethau mwyaf golygfaol. Mae pwysau twristiaeth wedi newid y cymeriad diwylliannol. Dyma’r AHNE gyntaf a ddynodwyd yn y Deyrnas Unedig ym 1956, ac y mae’r glannau wedi’u dynodi’n Arfordir Treftadaeth, hefyd. www.naturalresources.wales NLCA39 Gower - Page 1 of 11 Erys yr ardal yn un wledig iawn. Mae’r trumiau’n ffurfio cyfres o rostiroedd uchel, graddol, agored. Rheng y bryniau ceir tirwedd amaethyddol gymysg, yn amrywio o borfeydd bychain â gwrychoedd uchel i gaeau mwy, agored. Yn rhai mannau mae’r hen batrymau caeau lleiniog yn parhau, gyda thirwedd “Vile” Rhosili yn oroesiad eithriadol. Ar lannau mwy agored y gorllewin, ac ar dir uwch, mae traddodiad cloddiau pridd a charreg yn parhau, sy’n nodweddiadol o ardaloedd lle bo coed yn brin. Nodwedd hynod yw’r gyfres o ddyffrynnoedd bychain, serth, sy’n aml yn goediog, sydd â’u nentydd yn aberu ar hyd glannau’r de. -

(Lds) May 2020 Delivering the Rdp Leader Programme in Swansea

RDP LEADER 2014-2020 SWANSEA COUNCIL LOCAL DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY (LDS) MAY 2020 DELIVERING THE RDP LEADER PROGRAMME IN SWANSEA Location: Lliw Reservoir, Mawr Ward NAME OF LOCAL ACTION GROUP (LAG) AND CONTACT DETAILS Name of Swansea Rural Development Partnership LAG Administrative Body Primary Contact (also known as LAG Official) Name Victoria Thomson Tel 077962 75087 E-mail [email protected] Address Planning & City Regeneration Swansea Council Oystermouth Road Swansea SA1 3SN Administrative Body Secondary Contact Name Clare James Tel 07980 939678 E-mail [email protected] Address Planning & City Regeneration Swansea Council Oystermouth Road Swansea SA1 3SN LOCAL DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY IMPLEMENTATION TIMESCALES Start Date 1 July 2015 End Date 30 June 2023 Preface: Please note this is the fourth version of the LDS. Two earlier editions, dated September 2014 and March 2016, covered in detail the setting up of the programme and the various administrative systems. A further, third, November 2017 version retained some of this information but also more accurately reflected the, then, current position with the programme and delivery. This fourth edition brings us up-to-date and reflects the resolution by the Swansea Rural Development Partnership to align this strategy with the One Planet framework and approach. It was compiled by Helen Grey, External Funding Programme Officer. v4, May 2020. Copies of the previous LDS are available upon request from [email protected] Page 2 of 88 Table of Contents Foreword from Chair