Offender Supervision with Electronic Technology: a User's Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Announcement the International Historical, Educational, Charitable and Human Rights Society Memorial, Based in Moscow, Asks

Network of Concerned Historians NCH Campaigns Year Year Circular Country Name original follow- up 2017 88 Russia Yuri Dmitriev 2020 Announcement The international historical, educational, charitable and human rights society Memorial, based in Moscow, asks you to sign a petition in support of imprisoned historian and Gulag researcher Yuri Dmitriev in Karelia. The petition calls for Yuri Dmitriev to be placed under house arrest for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic or until his court case is over. The petition can be signed in Russian, English, French, Italian, German, Hebrew, Polish, Czech, and Finnish. It can be found here and here. This is the second petition for Yuri Dmitriev. The first, from 2017, can be found here. Please find below: (1) a NCH case summary (2) the petition text in English. P.S. Another historian, Sergei Koltyrin – who had defended Yuri Dmitriev and was subsequently imprisoned under charges similar to his – died in a prison hospital in Medvezhegorsk, Karelia, on 2 April 2020. Please sign the petition immediately. ========== NCH CASE SUMMARY On 13 December 2016, the Federal Security Service (FSB) arrested Karelian historian Yuri Dmitriev (1956–) and held him in remand prison on charges of “preparing and circulating child pornography” and “depravity involving a minor [his foster child, eleven or twelve years old in 2017].” The arrest came after an anonymous tip: the individual and his motives, as well as how he got the private information, remain unknown. Dmitriev said the “pornographic” photos of his foster child were taken because medical workers had asked him to monitor the health and development of the girl, who was malnourished and unhealthy when he and his wife took her in at age three with the intention of adopting her. -

The Suppression of Communism Act

The Suppression of Communism Act http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.nuun1972_07 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org The Suppression of Communism Act Alternative title Notes and Documents - United Nations Centre Against ApartheidNo. 7/72 Author/Creator United Nations Centre against Apartheid; Yengwa, Massabalala B. Publisher Department of Political and Security Council Affairs Date 1972-03-00 Resource type Reports Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1972 Source Northwestern University Libraries Description INTRODUCTION. Criticism of Bill in Parliament and by the Bar. The real purpose of the Act. -

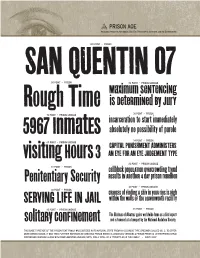

Prison AOE Specimen

PRISON AOE Available from the Astigmatic One Eye Typographic Institute and its Distributors SAN QUENTIN120 POINT - PRISON 07 96 POINT - PRISON 36 POINT - PRISON UNICASE Maximum seNTeNciNg Rough Time is DeteRmiNed By JurY 30 POINT - PRISON 72 POINT - PRISON UNICASE incarceration to start immediately 5967InmatEs absolutely no possibility of parole 24 POINT - PRISON 60 POINT - PRISON UNICASE CAPITAL PUNISHMENT ADMINISTERS visitIngHours3 AN EYE FOR AN EYE JUDGEMENT TYPE 20 POINT - PRISON UNICASE 54 POINT - PRISON cellblOck pOpULATIOn Overcrowding trend Penitentiary Security ResUlts iN AnotheR 4 dAY prisOn reBellion 18 POINT - PRISON UNICASE 48 POINT - PRISON CHanCEs of Finding A shiv in youR riBs is High SERVING LIFE IN JAIL withiN the wAlls oF the LeAvenwORth FaciliTy 42 POINT - PRISON UNICASE 16 POINT - PRISON The Birdman of Alcatraz gains worldwide fame as a bird expert solitaRy ConFINement and is honered at a banquet by the National Audubon Society THIS BASE TYPEFACE OF THE PRISON FONT FAMILY WAS DIGITIZED IN ITS NATURAL STATE FROM AN OLD WOOD TYPE SPECIMEN CALLED NO. 2. TO OFFER MORE DESIGN RANGE, IT WAS THEN FURTHER EXPANDED BY CREATING PRISON BREAK (A CRACKLED VERSION) & PRISON PRESS (A LETTERPRESS STYLE DISTRESSED VERSION) ALONG WITH COMPLIMENTING UNICASE SETS, FOR A TOTAL OF 6 TYPESTYLES IN THE FAMILY. - AOETI 2007 PRISON BREAK AOE Available from the Astigmatic One Eye Typographic Institute and its Distributors FUGITIVE120 POINT - PRISONESCAPE 96 POINT - PRISON 36 POINT - PRISON UNICASE waRDen JoHn FITzhuME Guards Hunt is UndER invEstigAtion -

Biographies of Main Political Leaders of Pakistan

Biographies of main political leaders of Pakistan INCUMBENT POLITICAL LEADERS ASIF ALI ZARDARI President of Pakistan since 2008 Asif Ali Zardari is the eleventh and current President of Pa- kistan. He is the Co-Chairman of the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), a role he took on following the demise of his wife, Benazir Bhutto. Zardari rose to prominence in 1987 after his marriage to Benazir Bhutto, holding cabinet positions in both the 1990s PPP governments, and quickly acquired a reputation for corrupt practices. He was arrested in 1996 after the dismissal of the second government of Bena- zir Bhutto, and remained incarcerated for eight years on various charges of corruption. Released in 2004 amid ru- mours of reconciliation between Pervez Musharraf and the PPP, Zardari went into self-imposed exile in Dubai. He re- turned in December 2007 following Bhutto’s assassination. In 2008, as Co-Chairman of PPP he led his party to victory in the general elections. He was elected as President on September 6, 2008, following the resignation of Pervez Musharraf. His early years in power were characterised by widespread unrest due to his perceived reluctance to reinstate the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court (who had been dismissed during the Musharraf imposed emergency of 2007). However, he has also overseen the passage of the 18th Amendment to the Constitution which effectively www.presidentofpakistan.gov.pk reduced presidential powers to that of a ceremonial figure- Asif Ali Zardari, President head. He remains, however, a highly controversial figure and continues to be dogged by allegations of corruption. Mohmmad government as Minister of Housing and Public Works. -

Investigation of the June 5, 2015 Escape of Inmates David Sweat and Richard Matt from Clinton Correctional Facility

State of New York Office of the Inspector General Investigation of the June 5, 2015 Escape of Inmates David Sweat and Richard Matt from Clinton Correctional Facility June 2016 Catherine Leahy Scott Inspector General STAFF FOR THIS INVESTIGATION AND REPORT SPENCER FREEDMAN JAMES CARROLL ELEANORE RUSSOMANNO Executive Deputy Inspector Deputy Chief Investigator Investigative Auditor General (Downstate Region) (Upstate Region) MICHELE HOST DENNIS GRAVES JASON FAZIO Chief Counsel Supervising Investigative Investigator Auditor (Upstate Region) (Upstate Region) JAMES R. DAVIS Deputy Inspector General FRANK RISLER ROBERTO SANTANA (Upstate) Chief Investigator Investigator Digital Forensics Lab (Downstate Region) BERNARD S. COSENZA Deputy Inspector General PETER AMOROSA JOSHUA WAITE of Investigations Investigative Auditor Senior Investigator (Upstate Region) (Upstate Region) SHERRY AMAREL Chief Investigator JOHN MILGRIM ROBERT PAYNE (Upstate Region) Special Deputy for Investigator Communications (Upstate Region) JAMES L. BREEN Investigative Counsel (Upstate) JEFFREY HAGEN GARY WATERS Deputy Inspector General Investigator DANIEL WALSH (Western Region) (Upstate Region) Deputy Chief Investigator (Upstate Region) STEPHEN DEL GIACCO STEPHANIE WORETH Director of Investigative Investigator ERIN BACH–LLOYD Reporting (Upstate Region) Investigator (Upstate Region) (Upstate Region) KATHERINE GEARY ANA PENN AMY T. TRIDGELL Special Assistant Investigator (Upstate Region) Director of Investigative (Upstate Region) Reporting (Downstate Region) JEFFREY HABER KELLY -

Unit on Apartheid Papers

Unit on Apartheid Papers No. 14/70 NOTES AND DOCUMENTS* May 1970 This Is Apartheid - II Pajge APARTHEID DAY BY DAY 1 South African Muslims protest demolition of mosques 1 White delighted at "redassification" as Coloured 2 Witwatersrand Principal denounces police intimidation of students and staff 3 Police spy on student leaders 4 Dutch theologian calls South Africa "police state" 4 Swedish archbishop shocked 4 No "white" eggs for Blacks in a Volksrust chain store 5 Poor matriculation results 5 African painters in Transvaal may apply first coat of paint, tout not the second 6 High school student released after eight months T detention 7 Mr. Eli Weinberg and Mr, Ivan Schermbrucker placed under house arrest on release from jail 8 Chinese barred from sports in South Africa 9 Lying spy remains free 10 She turns non-white to marry a Chinese 12 MORE FACTS AND FIGURES ON APARTHEID 15 WORLD AGAINST APARjgiEID 20 Reports from Canada, Uni-bed Republic of Tanzania, Ireland, Zambia, United Kingdom, Japan, Australia, *AHmaterias in these notes and documents may be freely reprinted. Acknowledgement, together with a copy of the publication containing the reprint, would be appreciated. Apartheid Day by Day South_ AJ^.Cjan_Nij^ The Musli-Hi community in South Africa is strongly protesting the recent threat to demolish the Pier Street Mosque in Port Elizabeth (which is in an area recently proclaimed a "white area") and the threatened demolition of many other mosques. A petition which is being circulated among worshippers at mosques all over the country explains that Islamic law lays down that no mosque or ground on which it is "built can be sold, given away or bartered. -

A Journal of African Studies

UCLA Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies Title The Autobiographical Nature of the Poetry of Dennis Brutus Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3gr609mz Journal Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies, 7(2) ISSN 0041-5715 Author Ssensalo, Bede M. Publication Date 1977 DOI 10.5070/F772017428 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California 130 ISSlfS: lliE AUTOBICXJRAPh iCAI.. NATURE OF lliE P0CIRY OF IEtJIS BIIDUS* by Bede M. Ssensalo 'n1e Nigerian poet, J . P . Clark once criticized Dennis Brutus for writing such lires as "c::bsrene albinos" - a refer ence to white South Africans. But what we have to lmderstarrl is that Nigerians are not IlUl:dered or .inprisoned because of the color of their skin. To quote Paul Theroux, "Nigerians are not the stinking lubrication that helps the huge cogs of the econ~ nm 51000thly. "1 Brutus has been whipped, put under house arrest jailed in the notorious Rcbben Island and even shot. So when he lashes bade, he does so furiously. Although it is true that saret..ines his pundles are wild, that saret..ines he misses, it is my hope that during the course of this article we shall see hiln swing enough ti.Jres to see what he is a::iriting at. All art is autcbiographical in that it is inspired by the artist' s own personal life. Yet we find that in varying degrees 1 the western artist can and indeed has sucoeeded in pursuing the reflections and images that are dear to him as a private individual. -

Gulag Vs. Laogai

GULAG VS. LAOGAI THE FUNCTION OF FORCED LABOUR CAMPS IN THE SOVIET UNION AND CHINA Sanne Deckwitz (3443639) MA International Relations in Historical Perspective Utrecht University Supervisor: Prof. dr. B.G.J. de Graaff Second Reader: Dr. L. van de Grift January 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations and Acronyms.................................................................................................. ii Maps…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… iii Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………………………... 1 Chapter 1: Historical overview of the gulag…………………………………………………………... 6 1.1 Origins of the gulag, 1918-1929…………………………………………………………… 6 1.2 Stalin’s gulag, 1929-1953…………………………………………………………………….. 9 1.3 The gulag after Stalin, 1953-1992………………………………………………………… 14 Chapter 2: Historical overview of the laogai………………………………………………………….. 17 2.1 Origins of the laogai, 1927-1949…………………………………………………………... 18 2.2 The laogai during the Mao Era, 1949-1976…………………………………………… 20 2.3 The laogai after Mao, 1976-present……………………………………………………… 26 Chapter 3: The political function of the gulag and the laogai………………………………….. 29 3.1 Rule by the vanguard party of the proletariat……………………………………….. 29 3.2 Classicide: eliminating external enemies………………………………………………. 32 3.3 Fracticide: eliminating internal enemies………………………………………………. 34 3.4 China’s capitalist communism……………………………………………………………… 37 Chapter 4: The economical function of the gulag and the laogai ...............………………….. 40 4.1 Fulfilling the economic goals of socialism……………………………………………... 41 4.2 -

A Comparison of Success Rates for House Arrest Inmates and Community Treatment Center Residents

A COMPARISON OF SUCCESS RATES FOR HOUSE ARREST INMATES AND COMMUNITY TREATMENT CENTER RESIDENTS By MINU MATHUR lj Bachelor of Arts Delhi University Delhi , I nd i a 1972 Master of Science Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 1981 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 1987 T\\~s\$ \'1~'1\::> M'i~~~ Co\'·~ A COMPARISON OF SUCCESS RATES FOR HOUSE-.......__,_.. ARREST INMATES AND COMMUNITY TREATMENT CENTER RESIDENTS Thesis Approved: Dean of the Graduate College i i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am indebted to a number of people for having helped, encouraged, and guided me during the course of my studies at Oklahoma State University. A great source of encouragement and guidance has been my adviser, Dr. Harjit Sandhu. I gratefully acknowledge the help and support which he provided far beyond the call of duty. I am also indebted to Dr. Richard Dodder, who has provided hours of help on computer and elsewhere. I am also grateful to Dr. Larry Perkins and Dr. Robert Greer for their encouragement and willingness to edit this paper. A special thanks is offered to the Oklahoma Department of Correc tions for providing me with the opportunity to study inmates. Thanks to all the inmates who shared sensitive information about themselves with me. And, of course, this study could not have been possible without the help and support of Dr. Steve Davis, Supervisor of Research and Planning, Oklahoma Department of Corrections, who patiently sent me data for well over two years. -

Assessing Pakistan's Election

Assessing Pakistan’s Election Wendy J. Chamberlin President, The Middle East Institute United States Ambassador to Pakistan, 2001-2002 United States Ambassador to Laos, 1996-1999 omething very positive just happened in “the most dangerous country in the world.” Pakistan surprised the chorus of pundits who predicted the parlia- S mentary elections held on February 18, 2008, would not be credible, and the public reaction would turn violent. Instead, Pakistan made history. For the first time in its tumultuous history, a military dictator participated in the peaceful transition to civilian government through democratic elections. To his credit, President Pervez Musharraf responded to internal and international pressure to lift Emergency Rule and to step down as Chief of Army Staff. Nothing is ever as simple as it appears. Just before he relinquished his position as Chief of Army Staff, President Musharraf imposed Emergency Rule. Some call it a military coup. He used the month-long period of Emergency Rule from November 3 to December 15 to change the constitution by fiat in order to remove provisions that made him ineligible to continue as president. His widespread crackdown on independent journalists, judges and lawyers intimidated liberal democratic voices in Pakistan that championed rule of law and democracy.* During Emergency Rule, he also sacked the Supreme Court Chief Iftikhar Chaudhry (who is still under house arrest) and required other judges to take a loyalty oath, leading to the dismissal of some 60 judges. In addition, he assured the Electoral Commission was stacked with his loyalists so that irregularities in the upcoming election would go unheeded. -

Prison Break: Why Conservatives Turned Against Mass Incarceration

AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE PRISON BREAK: WHY CONSERVATIVES TURNED AGAINST MASS INCARCERATION INTRODUCTION AND MODERATOR: SALLY SATEL, AEI PANEL DISCUSSION PANELISTS: HEATHER MACDONALD, MANHATTAN INSTITUTE; HAROLD POLLACK, UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO; VIKRANT REDDY, CHARLES KOCH INSTITUTE; STEVEN TELES, JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY 10:30 AM – 12:00 PM TUESDAY, MAY 24, 2016 EVENT PAGE: http://www.aei.org/events/prison-break-why-conservatives-turned- against-mass-incarceration/ TRANSCRIPT PROVIDED BY DC TRANSCRIPTION – WWW.DCTMR.COM SALLY SATEL: Welcome everybody. My name is Sally Satel. I’m a resident scholar at AEI, and very excited today to have our book panel on a fascinating book by Steve Teles and his coauthor, who will join us for Q&A later, David Daga called “Prison Break: Why Conservatives Turned against Mass Incarceration.” The book is about the embrace of prison reform by the right and the story really of what Steve and David call trans-partisanship, not quite the same as bipartisanship, as they’ll explain, and how that’s led to new agreements and new legislation regarding who and how to imprison. Also, seductively, the book touches on how to generate policy breakthroughs in a time of a great political polarization — something like we have today. Clearly, it’s a very timely issue of legislation on sentencing reform is winding its way through — tumultuously, through the Hill. And very recently, in fact, FBI Director James Comey made comments that, frankly, strike me as quite accurate but are certainly inflammatory, about the rising crime rates. So all of that’s going on in the backdrop. So today we’re going to start with a presentation by Steve on the book’s major themes, the dynamics of the right on crime movement. -

A. the International Bill of Human Rights

A. THE INTERNATIONAL BILL OF HUMAN RIGHTS 1. Universal Declaration of Human Rights Adopted and proclaimed by General Assembly resolution 217 A (III) of 10 December 1948 PREAMBLE Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world, Whereas disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind, and the advent of a world in which human beings shall enjoy freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear and want has been proclaimed as the highest aspiration of the common people, Whereas it is essential, if man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, that human rights should be pro- tected by the rule of law, Whereas it is essential to promote the development of friendly relations between nations, Whereas the peoples of the United Nations have in the Charter reaffirmed their faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person and in the equal rights of men and women and have determined to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom, Whereas Member States have pledged themselves to achieve, in co-operation with the United Nations, the promotion of universal respect for and observance of human rights and fundamental freedoms, Whereas a common understanding of these rights and freedoms is of the great- est importance for the full realization