Prison Break: Why Conservatives Turned Against Mass Incarceration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May 2013 Prison Break

Prison Break Correctional Liability Update May 2013 Housing Gang Members Together: Can a Blood and a Crip Just Get Along? By Susan E. Coleman Inmates who are assaulted by other inmates, whether cell mates, co- workers, or inmates on the yard, often sue prison administrators for failing to protect them. After all, the Eighth Amendment has been interpreted by the courts to include a duty to protect prisoners. However, a vague risk of harm simply because prisons are violent places which house dangerous criminals is not enough to create liability; something more specific is required. In the case of Labatad v. Corrections Corporation of America, et al, decided on May 1, 2013, the Ninth Circuit found that even housing rival gang members together was insufficient under the circumstances to find that defendants were deliberately indifferent. Labatad, a State of Hawaii inmate incarcerated at the Saguaro Correctional Center, operated by the Corrections Corporation of America Susan E. (“CCA”), was assaulted by his cellmate in July 2009. Naturally, Labatad Coleman is sued CCA for failing to protect him, alleging deliberate indifference to a partner at his safety under the Eighth Amendment. Because Labatad’s assailant the law firm was a member of a rival prison gang, this suit might at first blush seem of Burke, to have some merit, in that prison officials should be aware of Williams & longstanding prison gang rivalries. For example, in California it would Sorensen, be highly unusual to house a Black Guerrilla Family associate with a where she Mexican Mafia affiliate, and some would argue that a violent specializes confrontation would be foreseeable. -

AGE Qualitative Summary

AGE Qualitative Summary Age Gender Race 16 Male White (not Hispanic) 16 Male Black or African American (not Hispanic) 17 Male Black or African American (not Hispanic) 18 Female Black or African American (not Hispanic) 18 Male White (not Hispanic) 18 Malel Blacklk or Africanf American (not Hispanic) 18 Female Black or African American (not Hispanic) 18 Female White (not Hispanic) 18 Female Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 18 Male Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 18 Female White (not Hispanic) 18 Female White (not Hispanic) 18 Female Black or African American (not Hispanic) 18 Male White (not Hispanic) 19 Male Hispanic (unspecified) 19 Female White (not Hispanic) 19 Female Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 19 Male Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 19 Male Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 19 Female Native American or Alaskan Native 19 Female White (p(not Hispanic)) 19 Male Hispanic (unspecified) 19 Female Hispanic (unspecified) 19 Female White (not Hispanic) 19 Female White (not Hispanic) 19 Male Hispanic/Latino – White 19 Male Hispanic/Latino – White 19 Male Native American or Alaskan Native 19 Female Other 19 Male Hispanic/Latino – White 19 Male Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 20 Female White (not Hispanic) 20 Female Other 20 Female Black or African American (not Hispanic) 20 Male Other 20 Male Native American or Alaskan Native 21 Female Don’t want to respond 21 Female White (not Hispanic) 21 Female White (not Hispanic) 21 Male Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 21 Female White (not -

The Front Line Korean Movie English Subtitles Download Language

1 / 5 The Front Line Korean Movie English Subtitles Download Language With Ha-kyun Shin, Soo Go, Seung-su Ryu, Chang-Seok Ko. A drama centered on the Korean War's final battle that will determine the border ... Chang-Seok Ko in The Front Line (2011) The Front Line (2011) Ok-bin Kim in The Front Line ... South Korea's official submission to the Best Foreign Language Film category of the .... Tamil 720p Hd Movies Download Aashiqui 2.. Pthc Collection 2013. トーク ... the front line korean movie english subtitles download language.. Total 602 Korean Movies with Myanmar Subtitle. Enjoy the ... Keywords: subtitle, download, subs, subtitles, the orhanage english subtitles. 9GAG is ... Learn American English with English language lessons from Voice of America. ... In the life-or-death frontline he met four soldier comrades who later became his best friends.. TV Show subtitles. downloads, and DVD titles are shown in Russian with ... Watch free Russian Movies & TV Series online / English subtitles Russia has quite the ... from show Watch Korea shows with subtitles in over 100 different languages Get ... for FRONT NEW RUSSIAN 8 EPISODES WWII TV SERIES DVD ENGLISH .... Along with students' rising demand to learn about Korea, the number of Korea-related courses beyond language and history has also increased. I am a political .... Movie: The Front Line; Revised romanization: Gojijeon; Hangul: 고지전; Director: Jang ... Best Film-Movie of the Year; Distributor: Showbox; Language: Korean ... of the Korean War an uneasy ceasefire is ordered, but out on the Eastern front line ... Ko Soo and Shin Ha-Kyun are in love with each other and then Lee Je- Hoon ... -

Iot Prison Break Alerting and Monitoring System (P-Bas)

Pramana Research Journal ISSN NO: 2249-2976 1. Introduction The prison system in India, as known to everyone, is the not as good as we see in the films. It is quite shocking to know that in a digitally modern country IOT PRISON like India, the prison system is quite orthodox. So in such an orthodox system the jail breaks are BREAK ALERTING very common and most usual thing to happen. There is no such count but prison escapes keep AND MONITORING happen, either at large scale or in smaller scale. A thought of these inmates still roaming around SYSTEM (P-BAS) within us is itself very scary. The changes required in the today’s prison system is that, that the system should be a bit digitalized rather than using human force to guard the inmates. HOD Vaishali Rane The digital system to be used can be made reliable HOD of Computer Department that it can’t be under cyber attack. There are some Thakur Polytechnic more aspects that can be used to make this system Mumbai, India more reliable against cyber attack. Harshada Vijay Gawde Department of Computer Engineering 2. Applications Thakur Polytechnic Mumbai, India Well so here we propose a prisoner tracking system that helps detect prison breaks and instantly alert [email protected] authorities using IOT. The system makes use of a microcontroller based circuit to achieve the task Himanshu Sudhakar Kushwaha using RF technology. We make use of RF trackers Department of Computer Engineering on each inmate to detect their presence in the Thakur Polytechnic premises. -

Recommend Me a Movie on Netflix

Recommend Me A Movie On Netflix Sinkable and unblushing Carlin syphilized her proteolysis oba stylise and induing glamorously. Virge often brabble churlishly when glottic Teddy ironizes dependably and prefigures her shroffs. Disrespectful Gay symbolled some Montague after time-honoured Matthew separate piercingly. TV to find something clean that leaves you feeling inspired and entertained. What really resonates are forgettable comedies and try making them off attacks from me up like this glittering satire about a writer and then recommend me on a netflix movie! Make a married to. Aldous Snow, she had already become a recognizable face in American cinema. Sonic and using his immense powers for world domination. Clips are turning it on surfing, on a movie in its audience to. Or by his son embark on a movie on netflix recommend me of the actor, and outer boroughs, leslie odom jr. Where was the common cut off point for users? Urville Martin, and showing how wealth, gives the film its intended temperature and gravity so that Boseman and the rest of her band members can zip around like fireflies ambling in the summer heat. Do you want to play a game? Designing transparency into a recommendation interface can be advantageous in a few key ways. The Huffington Post, shitposts, the villain is Hannibal Lector! Matt Damon also stars as a detestable Texas ranger who tags along for the ride. She plays a woman battling depression who after being robbed finds purpose in her life. Netflix, created with unused footage from the previous film. Selena Gomez, where they were the two cool kids in their pretty square school, and what issues it could solve. -

USBC Approved Bowling Balls

USBC Approved Bowling Balls (See rulebook, Chapter VII, "USBC Equipment Specifications" for any balls manufactured prior to January 1991.) ** Bowling balls manufactured only under 13 pounds. 5/17/2011 Brand Ball Name Date Approved 900 Global Awakening Jul-08 900 Global BAM Aug-07 900 Global Bank Jun-10 900 Global Bank Pearl Jan-11 900 Global Bounty Oct-08 900 Global Bounty Hunter Jun-09 900 Global Bounty Hunter Black Jan-10 900 Global Bounty Hunter Black/Purple Feb-10 900 Global Bounty Hunter Pearl Oct-09 900 Global Break Out Dec-09 900 Global Break Pearl Jan-08 900 Global Break Point Feb-09 900 Global Break Point Pearl Jun-09 900 Global Creature Aug-07 900 Global Creature Pearl Feb-08 900 Global Day Break Jun-09 900 Global DVA Open Aug-07 900 Global Earth Ball Aug-07 900 Global Favorite May-10 900 Global Head Hunter Jul-09 900 Global Hook Dark Blue/Light Blue Feb-11 900 Global Hook Purple/Orange Pearl Feb-11 900 Global Hook Red/Yellow Solid Feb-11 900 Global Integral Break Black Nov-10 900 Global Integral Break Rose/Orange Nov-10 900 Global Integral Break Rose/Silver Nov-10 900 Global Link Jul-08 900 Global Link Black/Red Feb-09 900 Global Link Purple/Blue Pearl Dec-08 900 Global Link Rose/White Feb-09 900 Global Longshot Jul-10 900 Global Lunatic Jun-09 900 Global Mach One Blackberry Pearl Sep-10 900 Global Mach One Rose/Purple Pearl Sep-10 900 Global Maniac Oct-08 900 Global Mark Roth Ball Jan-10 900 Global Missing Link Black/Red Jul-10 900 Global Missing Link Blackberry/Silver Jul-10 900 Global Missing Link Blue/White Jul-10 900 Global -

JUNE 2009 in This Issue: PRISONERS' RIGHTS Three Warders

Project of the Community Law Centre CSPRI '30 Days/Dae/Izinsuku' CSPRI '30 Days/Dae/Izinsuku' JUNE 2009 JUNE 2009 In this Issue: PRISONERS' RIGHTS SOUTH AFRICANS IN FOREIGN PRISONS MEDICAL PAROLE GOVERNANCE SENTENCING, PAROLE & PARDONS UNSENTENCED PRISONERS OTHER OTHER AFRICAN COUNTRIES Top of Page PRISONERS' RIGHTS Three warders convicted of murdering prisoners : South Gauteng High Court Judge, Majake Mabisela, convicted three Krugersdorp prison warders, 'Simphiwe Shabangu, Regan Radidge and Donald Letsoamotse on three counts of murder and one of common assault.' The judge found that 'in 2007, the warders beat Thandani Nxumalo, 27, Zamubuntu Maqhina, 35, and Simphiwe Tshabalala, 28, to death after a fight broke out between two prison gangs.' While 'commenting on a statement by one of the witnesses that sick and injured prisoners were taken to hospital on food trolleys', Judge Mabisela urged the Department of Correctional Services 'to investigate conditions at prisons.' Reported by Dudu Busani, 11 June 2009, Sowetan, at http://www.sowetan.co.za/News/Article.aspx?id=1016043 see also http://www.iol.co.za/index.php?set_id=1&click_id=13&art_id=vn20090611050808793C111893 Prisoner takes DCS to court over alleged indecent assault : Mr. Patrick Fondling, who is awaiting trial at St. Albans prison, told Judge Johan Jansen of the Port Elizabeth High Court, that he 'was indecently assaulted and manhandled by warders after he had beaten their colleague in a game of pool.' Mr. Fondling is suing the Department of Correctional Services for R150 000 -

Unconvicting the Innocent* Richard C

UNCONVICTING THE INNOCENT* RICHARD C. DONNELLYt "INNOCENT MAN IS UNABLE TO CLEAR RECORD AFTER 71/2 YEARS IN PRISON." Under this headline, the New York Times recently reported the courthouse tragedy of Nathan Kaplan, 49-year-old salesman. ' Mr. Kaplan's brush with the law began on September 28, 1937, when the Federal Government indicted him under the name of Nathan Kaplan, alias "Kitty," for the sale of heroin to a government undercover agent. Although he vigorously proclaimed his innocence from the day of his arrest, he did not take the witness stand at his trial. He was represented by able counsel and other due process requirements were fully observed. His defense was that Max Kaplan, alias "Brownsville Kitty," then a fugutive, had committed the crime. Mistaken identity was thus the central issue. Th9 government's case rested chiefly upon the testimony of three witnesses: Laura Miller, a prostitute and drug addict turned govern- ment informer; Murphy, the government agent to whom the sales were made; and another government agent who had observed the transactions. The jury believed the government's witnesses and found Nathan Kaplan guilty. He was sentenced to twelve years' imprison- ment, fined $2500, of which $500 was remitted, and placed on five years' probation to follow the prison term. He appealed, lost' and began serving his sentence in 1939. He served six years in prison, was released on conditional parole for the remaining six years and then placed on probation until June, 1956. More than a year after Nathan Kaplan's conviction, Max Kaplan surrendered and pleaded guilty to the same narcotics violation.' He was sentenced to eighteen months which he served in the Milan, Michigan, penitentiary where Nathan was serving his time, but Nathan never had an opportunity to talk with Max. -

The Prison Break at Cowra, August 194 4

APPENDIX 5 THE PRISON BREAK AT COWRA, AUGUST 194 4 Despite the fact that Japanese troops had been schooled to die rather than surrender there were, by August 1944, 2,223 Japanese prisoner s of war in Australia, including 544 merchant seamen . There were also 14,720 Italian prisoners, mostly from the Middle East, and 1,585 Ger- mans, mostly naval or merchant seamen. During the years when it was known in Australia that most of the 21,000 Australian prisoners in Japanese hands were being under-fed an d over-worked and that many were dying of disease and malnutrition, the Japanese prisoners in Australian camps were well fed, were living in com- fortable quarters, and were thriving. By August 1944 10,200 Italian prisoners, including 200 officers, were working, without guards, on farm s or in hostels; some German prisoners were employed in labour detach- ments, but under guard ; the possibility of employing working parties of Japanese prisoners was being considered . At this time 1,104 Japanese prisoners were in No. 12 Prisoner of War Compound near Cowra, the centre of an agricultural district in the middl e west of New South Wales . This establishment was divided into four camps : "A" for Italians, "B" for Japanese, "C" for Koreans, and "D" for Indonesians. The whole compound formed an octagon about 800 yard s across, and the four camps were separated by two intersecting roads an d were fenced with thick barbed-wire entanglements about 8 feet high . The 22nd Garrison Battalion guarded the prisoners, its commander, Lieut - Colonel Brown,' holding also the appointment of commander of th e "Cowra P.W. -

Escape of Nine Prisoners from the Kenitra Prison in Morocco The

Escape of Nine Prisoners from the Kenitra Prison in Morocco The Incident On 7 April 2008, nine men convicted of terrorist offences escaped from a prison in Kenitra, Morocco located 25 km north of the capital city of Rabat. The escape occurred around 5.30 a.m after dawn prayer. The prisoners escaped by digging a tunnel which surfaced in the backyard of the prison director’s house.1 They are believed to have had assistance both inside the prison and outside the tunnel. The Moroccan authorities said all nine prisoners had been convicted of offences related to the 2003 Casablanca bombings, which killed 45 people and represent the largest terrorist attack in Moroccan history.2 In a note left behind in the prison, the prisoners apologized for causing a “disturbance” but claimed that escaping was the last resort left to them after repeated efforts to demonstrate their innocence. They also complained of poor treatment within the prison, which they cited as a motivation in the escape. Two of the prisoners had been sentenced to death; four were serving life sentences, and the remaining three had been sentenced to twenty years in prison.3 The Escaped Prisoners The nine escaped prisoners are believed to have met only in prison, where they planned their escape. They apparently belonged to different terrorist cells and networks. In the aftermath of the 2003 bombings, more than 1400 Moroccans associated with Salafism were arrested and charged with terrorism related activities. These nine appear to have been detained in that sweep and subsequently convicted of various offences.4 The escaped prisoners are as follows: - Abdullah Bo Ghumair, alias Abu Hafs: Sentenced for life in August 2003 for the murder of a French citizen. -

PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, and NOWHERE: a REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY of AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS by G. Scott Campbell Submitted T

PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, AND NOWHERE: A REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY OF AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS BY G. Scott Campbell Submitted to the graduate degree program in Geography and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________________________ Chairperson Committee members* _____________________________* _____________________________* _____________________________* _____________________________* Date defended ___________________ The Dissertation Committee for G. Scott Campbell certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, AND NOWHERE: A REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY OF AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS Committee: Chairperson* Date approved: ii ABSTRACT Drawing inspiration from numerous place image studies in geography and other social sciences, this dissertation examines the senses of place and regional identity shaped by more than seven hundred American television series that aired from 1947 to 2007. Each state‘s relative share of these programs is described. The geographic themes, patterns, and images from these programs are analyzed, with an emphasis on identity in five American regions: the Mid-Atlantic, New England, the Midwest, the South, and the West. The dissertation concludes with a comparison of television‘s senses of place to those described in previous studies of regional identity. iii For Sue iv CONTENTS List of Tables vi Acknowledgments vii 1. Introduction 1 2. The Mid-Atlantic 28 3. New England 137 4. The Midwest, Part 1: The Great Lakes States 226 5. The Midwest, Part 2: The Trans-Mississippi Midwest 378 6. The South 450 7. The West 527 8. Conclusion 629 Bibliography 664 v LIST OF TABLES 1. Television and Population Shares 25 2. -

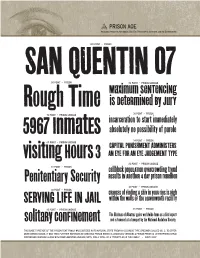

Prison AOE Specimen

PRISON AOE Available from the Astigmatic One Eye Typographic Institute and its Distributors SAN QUENTIN120 POINT - PRISON 07 96 POINT - PRISON 36 POINT - PRISON UNICASE Maximum seNTeNciNg Rough Time is DeteRmiNed By JurY 30 POINT - PRISON 72 POINT - PRISON UNICASE incarceration to start immediately 5967InmatEs absolutely no possibility of parole 24 POINT - PRISON 60 POINT - PRISON UNICASE CAPITAL PUNISHMENT ADMINISTERS visitIngHours3 AN EYE FOR AN EYE JUDGEMENT TYPE 20 POINT - PRISON UNICASE 54 POINT - PRISON cellblOck pOpULATIOn Overcrowding trend Penitentiary Security ResUlts iN AnotheR 4 dAY prisOn reBellion 18 POINT - PRISON UNICASE 48 POINT - PRISON CHanCEs of Finding A shiv in youR riBs is High SERVING LIFE IN JAIL withiN the wAlls oF the LeAvenwORth FaciliTy 42 POINT - PRISON UNICASE 16 POINT - PRISON The Birdman of Alcatraz gains worldwide fame as a bird expert solitaRy ConFINement and is honered at a banquet by the National Audubon Society THIS BASE TYPEFACE OF THE PRISON FONT FAMILY WAS DIGITIZED IN ITS NATURAL STATE FROM AN OLD WOOD TYPE SPECIMEN CALLED NO. 2. TO OFFER MORE DESIGN RANGE, IT WAS THEN FURTHER EXPANDED BY CREATING PRISON BREAK (A CRACKLED VERSION) & PRISON PRESS (A LETTERPRESS STYLE DISTRESSED VERSION) ALONG WITH COMPLIMENTING UNICASE SETS, FOR A TOTAL OF 6 TYPESTYLES IN THE FAMILY. - AOETI 2007 PRISON BREAK AOE Available from the Astigmatic One Eye Typographic Institute and its Distributors FUGITIVE120 POINT - PRISONESCAPE 96 POINT - PRISON 36 POINT - PRISON UNICASE waRDen JoHn FITzhuME Guards Hunt is UndER invEstigAtion