Notes on the Behavior of Three Cotingidae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brazil's Eastern Amazonia

The loud and impressive White Bellbird, one of the many highlights on the Brazil’s Eastern Amazonia 2017 tour (Eduardo Patrial) BRAZIL’S EASTERN AMAZONIA 8/16 – 26 AUGUST 2017 LEADER: EDUARDO PATRIAL This second edition of Brazil’s Eastern Amazonia was absolutely a phenomenal trip with over five hundred species recorded (514). Some adjustments happily facilitated the logistics (internal flights) a bit and we also could explore some areas around Belem this time, providing some extra good birds to our list. Our time at Amazonia National Park was good and we managed to get most of the important targets, despite the quite low bird activity noticed along the trails when we were there. Carajas National Forest on the other hand was very busy and produced an overwhelming cast of fine birds (and a Giant Armadillo!). Caxias in the end came again as good as it gets, and this time with the novelty of visiting a new site, Campo Maior, a place that reminds the lowlands from Pantanal. On this amazing tour we had the chance to enjoy the special avifauna from two important interfluvium in the Brazilian Amazon, the Madeira – Tapajos and Xingu – Tocantins; and also the specialties from a poorly covered corner in the Northeast region at Maranhão and Piauí states. Check out below the highlights from this successful adventure: Horned Screamer, Masked Duck, Chestnut- headed and Buff-browed Chachalacas, White-crested Guan, Bare-faced Curassow, King Vulture, Black-and- white and Ornate Hawk-Eagles, White and White-browed Hawks, Rufous-sided and Russet-crowned Crakes, Dark-winged Trumpeter (ssp. -

A Review of Animal-Mediated Seed Dispersal of Palms

Selbyana 11: 6-21 A REVIEW OF ANIMAL-MEDIATED SEED DISPERSAL OF PALMS SCOTT ZoNA Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, 1500 North College Avenue, Claremont, California 91711 ANDREW HENDERSON New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, New York 10458 ABSTRACT. Zoochory is a common mode of dispersal in the Arecaceae (palmae), although little is known about how dispersal has influenced the distributions of most palms. A survey of the literature reveals that many kinds of animals feed on palm fruits and disperse palm seeds. These animals include birds, bats, non-flying mammals, reptiles, insects, and fish. Many morphological features of palm infructescences and fruits (e.g., size, accessibility, bony endocarp) have an influence on the animals which exploit palms, although the nature of this influence is poorly understood. Both obligate and opportunistic frugivores are capable of dispersing seeds. There is little evidence for obligate plant-animaI mutualisms in palm seed dispersal ecology. In spite of a considerable body ofliterature on interactions, an overview is presented here ofthe seed dispersal (Guppy, 1906; Ridley, 1930; van diverse assemblages of animals which feed on der Pijl, 1982), the specifics ofzoochory (animal palm fruits along with a brief examination of the mediated seed dispersal) in regard to the palm role fruit and/or infructescence morphology may family have been largely ignored (Uhl & Drans play in dispersal and subsequent distributions. field, 1987). Only Beccari (1877) addressed palm seed dispersal specifically; he concluded that few METHODS animals eat palm fruits although the fruits appear adapted to seed dispersal by animals. Dransfield Data for fruit consumption and seed dispersal (198lb) has concluded that palms, in general, were taken from personal observations and the have a low dispersal ability, while Janzen and literature, much of it not primarily concerned Martin (1982) have considered some palms to with palm seed dispersal. -

Wingspan Bird Tours Guyana

WINGSPAN BIRD TOURS IN GUYANA TRIP REPORT JANUARY 23RD – FEBRUARY 7TH 2015 LEADERS: BOB BUCKLER & LUKE JOHNSON PARTICIPANTS: REG COX, DAVID ROBERTS, GILL SIUDA, PATRICK & PEGGY CROWLEY, DAVID & ZOЁ EVANS, CAROL HOPPERTON AND LES BLUNDELL. PRE-TOUR EXTENSION TO TRINIDAD DAY 1 – 21st JANUARY 2015 – TRINIDAD Our first day was spent travelling, London Gatwick, to Port-of-Spain, Trinidad. It was getting dark as we arrived but as we emerged from the airport we managed to log Carib Grackle and Tropical Kingbird our very first sightings of the trip. We took a taxi to the ASA Wright Centre arriving just in time for dinner. We sat on the famous veranda sipping cool beers after dinner, anticipating our full day in the reserve tomorrow. DAY 2 – 22ND JANUARY 2015 - TRINIDAD ASA WRIGHT CENTRE ALL DAY Our first full day on tour, wow, it was marvellous. A Ferruginous Pygmy Owl woke me up at 4:30am it was right outside my window and I still couldn’t find it! At 6:15 there was enough light to bird from the ASA Wright veranda, we met there and chaos ensued as so many new species appeared at once . Within minutes the feeders were in full attendance, birds were everywhere¸ in the trees, on the ground, at the feeders and in every bush. A number of Tanagers were ever present: White-lined, Palm, Bay-headed, Blue and Gray and the beautiful Turquoise Tanager. These were out shone by the Green and the Purple Honeycreepers, Violaceous Euphonia, Bananaquit and of course the hummers. Tufted Coquette topped the list of hummer beauties, what a stunner. -

WILDLIFE TRAFFICKING in BRAZIL Sandra Charity and Juliana Machado Ferreira

July 2020 WILDLIFE TRAFFICKING IN BRAZIL Sandra Charity and Juliana Machado Ferreira TRAFFIC: Wildlife Trade in Brazil WILDLIFE TRAFFICKING IN BRAZIL TRAFFIC, the wildlife trade monitoring network, is a leading non-governmental organisation working globally on trade in wild animals and plants in the context of both biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. © Jaime Rojo / WWF-US Reproduction of material appearing in this report requires written permission from the publisher. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organisations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. TRAFFIC David Attenborough Building, Pembroke Street, Cambridge CB2 3QZ, UK. Tel: +44 (0)1223 277427 Email: [email protected] Suggested citation: Charity, S., Ferreira, J.M. (2020). Wildlife Trafficking in Brazil. TRAFFIC International, Cambridge, United Kingdom. © WWF-Brazil / Zig Koch © TRAFFIC 2020. Copyright of material published in this report is vested in TRAFFIC. ISBN: 978-1-911646-23-5 UK Registered Charity No. 1076722 Design by: Hallie Sacks Cover photo: © Staffan Widstrand / WWF This report was made possible with support from the American people delivered through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily -

(1) Carpornis Cucullatus E Nectandra Megapotamica (Lauraceae);

Figures 1-8. (1) Carpornis cucullatus e Nectandra megapotamica (Lauraceae); (2) Carpornis melanocephalus e Matayba elaeagnoides (Sapindaceae); (3) Lipaugus lanioides (regurgitando semente) e Tapirira guianensis (Anacardiaceae).; (4) Laniisoma elegans e Cordia ecalyculata (Boraginaceae); (5) Oxyruncus cristatus e Trema micrantha (Ulmaceae); (6) Phibalura flavirostris e Myrsine coriacea (Myrsinaceae); (7) Pyroderus scutatus e Euterpe edulis (Arecaceae); (8) Procnias nudicollis e Cupania vernalis (Sapindaceae). From a watercolor painting by Tomas Sigrist. 177 Ararajuba 10 (2): 177-185 dezembro de 2002 Frugivory in cotingas of the Atlantic Forest of southeast Brazil Marco A. Pizo 1, Wesley R. Silva 2, Mauro Galetti 3 and Rudi Laps 4 1 Author for correspondence. Departamento de Botânica, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade Estadual Paulista, Caixa Postal 199, 13506-900, Rio Claro, SP, Brasil. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Biologia, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Caixa Postal 6109, 13083-970, Campinas, SP, Brasil. E-mail: [email protected] 3 Instituto de Biologia da Conservação e Departamento de Ecologia, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade Estadual Paulista, Caixa Postal 199, 13506-900, Rio Claro, SP, Brasil. E-mail: [email protected] 4 Pós-graduação em Ecologia, Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Correspondência: Rua Rafael Bandeira, 162, bloco Marta, 301, 88015-450, Florianópolis, SC, Brasil. Recebido em 18 de setembro de 2002; aceito em 05 de novembro de 2002. RESUMO. Frugivoria em cotingídeos na Mata Atlântica do sudeste do Brasil. Neste trabalho apresentamos uma lista dos frutos comidos por oito espécies de cotingídeos (Carpornis cucullatus, C. melanocephalus, Laniisoma elegans, Lipaugus lanioides, Oxyruncus cristatus, Phibalura flavirostris, Procnias nudicollis e Pyroderus scutatus) no Parque Estadual Intervales (PEI), uma reserva de Mata Atlântica localizada no sudeste do Brasil. -

Notes on the Behavior of the White Bellbird

THE AUK A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ORNITHOLOGY VOL. 90 OCTOBEa 1973 NO. 4 NOTES ON THE BEHAVIOR OF THE WHITE BELLBIRD BARBARA K. SNow LITTLE has been recordedof the White Bellbird (Procniasalba) in the field. In March 1960 I made brief observationson a singleadult male in the Kanaku Mountains of southern Guyana, but my description of the displayswas very incomplete(B. K. Snow 1961, Auk 78: 150). In 1970 I again had the opportunity to return to the Kanaku Mountains. This time my husbandand I camped for nearly 3 months by Karusu Creek, a tributary of Moco Moco Creek, about 5 miles northwest of Nappi Creek where the earlier observationswere made. Since my last visit I had completeda 3-year study of the closely related Bearded Bellbird (Procnias averand) in Trinidad (B. K. Snow 1970, Ibis 112: 299). Adult males of the Bearded Bellbird are sedentary and advertise themselvesby loud calls from the sameperches in the forest throughout the year exceptfor the molt period. The females,who alone tend the nest, visit the males on their display perchesto mate, which is the only associationbetween the sexes. This speciesis entirely frugivorous,even the nestlingbeing fed only on fruit. In view of the apparently close relationshipof all the four speciesof Procnias, the same kind of be- havior and ecologyis to be expectedin the White Bellbird. The male White Bellbird is one of the few land birds with an entirely white plumage. The wattle growingfrom the baseof the upper mandible doesnot stick upwards,as shownin early illustrationsof the species, but hangs down and is extensible.The female is olive-greenabove, whitish-yellowwith darker streaksbelow, and lacks the wattle. -

Genetic Evidence Supports Song Learning in the Three

Molecular Ecology (2007) doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03415.x GeneticBlackwell Publishing Ltd evidence supports song learning in the three-wattled bellbird Procnias tricarunculata (Cotingidae) VINODKUMAR SARANATHAN,* DEBORAH HAMILTON,† GEORGE V. N. POWELL,‡ DONALD E. KROODSMA§ and RICHARD O. PRUM* *Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, and Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, PO Box 208105, New Haven, CT 06250 USA, †Costa Rican Conservation Foundation, Sede Ranario de Monteverde, Santa Elena, Puntarenas, Costa Rica, ‡Conservation Science Program, World Wildlife Fund, 1250 24th Street NW, Washington, DC 20037, USA, §Department of Biology, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA 01003, USA Abstract Vocal learning is thought to have evolved in three clades of birds (parrots, hummingbirds, and oscine passerines), and three clades of mammals (whales, bats, and primates). Behavioural data indicate that, unlike other suboscine passerines, the three-wattled bellbird Procnias tricarunculata (Cotingidae) is capable of vocal learning. Procnias tricarunculata shows conspicuous vocal ontogeny, striking geographical variation in song, and rapid temporal change in song within a population. Deprivation studies of vocal development in P. tricarunculata are impractical. Here, we report evidence from mitochondrial DNA sequences and nuclear microsatellite loci that genetic variation within and among the four allopatric breeding populations of P. tricarunculata is not congruent with variation in vocal behaviour. Sequences of the -

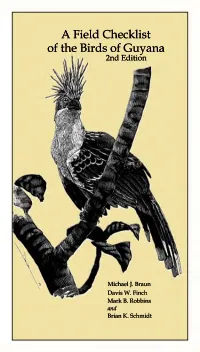

A Field Checklist of the Birds of Guyana 2Nd Edition

A Field Checklist of the Birds of Guyana 2nd Edition Michael J. Braun Davis W. Finch Mark B. Robbins and Brian K. Schmidt Smithsonian Institution USAID O •^^^^ FROM THE AMERICAN PEOPLE A Field Checklist of the Birds of Guyana 2nd Edition by Michael J. Braun, Davis W. Finch, Mark B. Robbins, and Brian K. Schmidt Publication 121 of the Biological Diversity of the Guiana Shield Program National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC, USA Produced under the auspices of the Centre for the Study of Biological Diversity University of Guyana Georgetown, Guyana 2007 PREFERRED CITATION: Braun, M. J., D. W. Finch, M. B. Robbins and B. K. Schmidt. 2007. A Field Checklist of the Birds of Guyana, 2nd Ed. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. AUTHORS' ADDRESSES: Michael J. Braun - Department of Vertebrate Zoology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, 4210 Silver Hill Rd., Suitland, MD, USA 20746 ([email protected]) Davis W. Finch - WINGS, 1643 North Alvemon Way, Suite 105, Tucson, AZ, USA 85712 ([email protected]) Mark B. Robbins - Division of Ornithology, Natural History Museum, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA 66045 ([email protected]) Brian K. Schmidt - Smithsonian Institution, Division of Birds, PO Box 37012, Washington, DC, USA 20013- 7012 ([email protected]) COVER ILLUSTRATION: Guyana's national bird, the Hoatzin or Canje Pheasant, Opisthocomus hoazin, by Dan Lane. INTRODUCTION This publication presents a comprehensive list of the birds of Guyana with summary information on their habitats, biogeographical affinities, migratory behavior and abundance, in a format suitable for use in the field. It should facilitate field identification, especially when used in conjunction with an illustrated work such as Birds of Venezuela (Hilty 2003). -

Territorial Behavior and Courtship of the Male Three-Wattled Bellbird

THE AUK A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ORNITHOLOGY VOL. 94 OCTOBER 1977 NO. 4 TERRITORIAL BEHAVIOR AND COURTSHIP OF THE MALE THREE-WATTLED BELLBIRD BARBARA K. SNOW ABSTRACT.---The Three-wattled Bellbird (Procnias tricarunculata) was studied for 7V2 weeks (April-June 1974)at Monteverde, CostaRica. In the studyarea, measuringapproximately 1,400 by 3,200 m, 13 adult males held territories from which they advertised themselvesby loud calls for 83-93% of the daylight hours. The majority had a repertoireof three different calls. Evidencefrom a tape recording from Panama and descriptionsfrom elsewhere in Costa Rica show that the Monteverdedialect is distinctive.Two individualshad part or all of their repertoiredifferent from other Monteverde males but matching vocalizations from elsewhere. Males call from exposed perchesabove the canopy and from a specialbroken-off branch, the visiting perch, beneath the canopy. Calling males perform two displaysinvolving flight, each precededby a characteristiccall. These displaysand a silent wattle-shakingdisplay are mainly performedwhen another bellbird visits a calling male. The visitors were usually females or immature males but occasionallyadult males. At the climax of the visit, the territow-holding male leans over his visitor, perchedat the broken-offend of the visitingperch, and utterssome extremely loud callsinto its ear. This usually makes the visitor leave. Both sexesreceive the same treatment. During May and June, females were watched comingto the visiting perchesof calling maleson 20 different occasions,but none of these visits culminated in mating. The male's wattles are fully extended when he is calling in his territory, but are usually retractedwhen he leaveshis territory to feed. During encountersbetween closelymatched males, first one and then the other may extendthe wattles and call. -

Neotropical Birds

HH 12 Neotropical Birds IRDSare a magnet that helps draw visitors to the Neotropics. Some come merely to augment an already long life list of species, wanting to see Bmore parrots, more tanagers, more hummingbirds, some toucans, and hoping for a chance encounter with the ever-elusive harpy eagle. Others, fol- lowing in the footsteps of Darwin, Wallace, and their kindred, investigate birds in the hopes of adding knowledge about the mysteries of ecology and evo- lution in this the richest of ecosystems. Opportunities abound for research topics. There are many areas of Neotropical ornithology that are poorly stud- ied, hardly a surprise given the abundance of potential research subjects. Like all other areas of tropical research, however, bird study is negatively affected by increasingly high rates of habitat loss. This chapter is an attempt to convey the uniqueness and diversity of a Neotropical avifauna whose richness faces a somewhat uncertain future. Avian diversity is very high in the Neotropics. The most recent species count totals 3,751 species representing 90 families, 28 of which are endemic to the Neotropics, making this biogeographic realm the most species-rich on Earth (Stotz et al. 1996). But seeing all 3,751 species will present a bit of a challenge. When Henry Walter Bates (1892) was exploring Amazonia, he was moved to comment on the difficulty of seeing Neotropical birds in dense rainforest: The first thing that would strike a new-comer in the forests of the Upper Amazons would be the general scarcity of birds: indeed, it often happened that I did not meet with a single bird during a whole day’s ramble in the richest and most varied parts of the woods. -

JOURNAL of TRINIDAD and TOBAGO: JUNE 16-25,1990 By

JOURNAL OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO: JUNE 16-25,1990 by John C. Kricher Editor’s Note. Thirteen birding friends led by John Kricher and dubbed The Darwin Group visited Trinidad and Tobago in June, at the beginning of the wet season. Several Bird Observer staffers were in the group and were so delighted with Professor Kricher’s informative daily journal of where we went and what we did that we decided to share it with our readers as a where-to-go feature. June 16, Saturday. Long travel day for the Darwin Group beginning at fogged-in Logan Airport, Boston, and ending with a star-filled, humid night in the Arima Valley of Trinidad. American Airlines got us to Miami by 10:30 A.M., and we proceeded directly to BWIA to check luggage and get seat assignments for the 3:00 P.M. flight. Lunch during the Miami layover. BWIA flight over the Caribbean was smooth with Captain Mickey Santos identifying various islands. Quick stop at Barbados, then on to Trinidad arriving well after dark. Jogie Ramlal, acknowledged premier guide to birds in Trinidad, and his crew were waiting to transport us to Asa Wright Nature Centre. Drive to AWC (on the left side of the road) was punctuated by frog whistles and boom boxes, the latter celebrating Saturday night on Trinidad. Upon our arrival at the Centre, the director introduced himself and supplied coffee, juice, and sandwiches. Cabin and room assignments were given, and we were off to unpack and bed down. Ferruginous Pygmy-Owls were vocalizing. June 17, Sunday. -

Birds of the Potaro Plateau, with Eight New Species for Guyana

Cotinga 18 Birds of the Potaro Plateau, w ith eight new species for Guyana Adrian Barnett, Rebecca Shapley, Paul Benjamin, Everton Henry and Michael McGarrell Cotinga 1 8 (2002): 19– 36 La meseta Potaro, en Guyana occidental, es un tepui de 11 655 ha. La meseta es la pieza más occidental del Escudo Guyanés. Con una altitud que va entre 500 y 2042 m, la vegetación oscila entre el matorral de arena blanca, bosque ribereño inundado, bosque de montaña típico de los tepuis, y matorral de tepui alto. Entre el 20 de junio y el 3 de agosto de 1998 se estudiaron las aves de la meseta, como parte de relevamientos zoológicos generales. Se registraron 187 especies de aves, de las cuales ocho ( Colibri coruscans, Polytmus milleri, Automolus roraimae, Lochmias nematura, Myrmothera simplex, Troglodytes rufulus, Diglossa major y Gymnomystax mexicanus) son nuevas para Guyana. Siete de estas especies son especialistas de bosque de montaña, y ya fueron registradas en la porción venezolana del Monte Roraima, a menos de 100 km al oeste de la meseta. La recopilación de datos, en su mayor parte inéditos, de la región de la meseta Potaro, resultó en un listado de 334 especies de aves, o 43% de las aves terrestres de Guyana. En la meseta habitan 21 de las 22 especies endémicas del Escudo Guyanés, y dos tercios de las especies de bosque de montaña en Guyana. Esta región debe ser considerada importante para la conservación de aves a nivel regional y nacional. Introduction on the Potaro Plateau from 13 June to 4 August We report here on bird observations from the Potaro 1998( the late wet season).