Writing@SVSU 2014–2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What's the Download® Music Survival Guide

WHAT’S THE DOWNLOAD® MUSIC SURVIVAL GUIDE Written by: The WTD Interactive Advisory Board Inspired by: Thousands of perspectives from two years of work Dedicated to: Anyone who loves music and wants it to survive *A special thank you to Honorary Board Members Chris Brown, Sway Calloway, Kelly Clarkson, Common, Earth Wind & Fire, Eric Garland, Shirley Halperin, JD Natasha, Mark McGrath, and Kanye West for sharing your time and your minds. Published Oct. 19, 2006 What’s The Download® Interactive Advisory Board: WHO WE ARE Based on research demonstrating the need for a serious examination of the issues facing the music industry in the wake of the rise of illegal downloading, in 2005 The Recording Academy® formed the What’s The Download Interactive Advisory Board (WTDIAB) as part of What’s The Download, a public education campaign created in 2004 that recognizes the lack of dialogue between the music industry and music fans. We are comprised of 12 young adults who were selected from hundreds of applicants by The Recording Academy through a process which consisted of an essay, video application and telephone interview. We come from all over the country, have diverse tastes in music and are joined by Honorary Board Members that include high-profile music creators and industry veterans. Since the launch of our Board at the 47th Annual GRAMMY® Awards, we have been dedicated to discussing issues and finding solutions to the current challenges in the music industry surrounding the digital delivery of music. We have spent the last two years researching these issues and gathering thousands of opinions on issues such as piracy, access to digital music, and file-sharing. -

Financial Supporters

FINANCIAL SUPPORTERS Care and Share Food Bank for Southern Colorado 2011-12 Financial Supporters 100% Chiropractic Lanny and Paul Adams Mr. and Mrs. Jeffrey Ahrendsen 14K Real Estate Investments LLC Ms. Laura Adams Mr. Kevin Ahrens 1882 Management Mr. and Mrs. Lon Adams Mr. and Mrs. Charles Aiken 1st Cavalry Rocky Mountain Chapter Col and Mrs. Louis Adams Ms. Laverne Ainley 221 South Oak Bistro Ms. Maggie Adams Air Academy Federal Credit Union 4-Bits 4-H Club Ms. Mary Adams Air Academy Federal Credit Union 4Clicks - Solutions, LLC Mr. Michael Adams Air Academy High School - District 20 A & L Aluminum Manufacturing Company Mr. and Mrs. Rexford Adams Mr. TJ Airhart A Handymike Home Repair Mr. and Mrs. Robert Adams Aka Wilson, LLC A to Z Realty Mr. S. Michael Adams Mr. Richard Alaniz AA “Accurate and Affordable” Striping, Inc. Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Adams Ms. Susan Alarid AAA NCNU Insurance Exchange Mr. Steve Adams Ms. Karin Alaska AAA Northern California Nevada & Utah Suzanne Adams Mr. Arturo Albanesi AARP Foundation Adams Bank & Trust Mr. and Mrs. Mac Alberico Ms. Renee Abbe Mrs. Alda Adcox Ms. Cheryl Alberto Ms. Marjory Abbott Add Staff Inc. Mr. and Mrs. Dewey Albertson Jr. Mr. and Mrs. Peyton Abbott Ms. Constance Addington Mr. W. Gary Albertson Ms. Stephanie Abbott Mr. and Mrs. D. V. Addington Albertsons LLC Ms. Brianna Abby Ms. Linda Addington Mr. and Mrs. Albert Albrandt Mr. and Mrs. Donald Abdallah Ms. Vicky Addison Mr. Gerald Albrecht Mr. Tony Abdella Ms. Deirdre Aden-Smith Ms. Patricia Albright Mr. and Mrs. William Abel Mr. -

2020 WWE Finest

BASE BASE CARDS 1 Angel Garza Raw® 2 Akam Raw® 3 Aleister Black Raw® 4 Andrade Raw® 5 Angelo Dawkins Raw® 6 Asuka Raw® 7 Austin Theory Raw® 8 Becky Lynch Raw® 9 Bianca Belair Raw® 10 Bobby Lashley Raw® 11 Murphy Raw® 12 Charlotte Flair Raw® 13 Drew McIntyre Raw® 14 Edge Raw® 15 Erik Raw® 16 Humberto Carrillo Raw® 17 Ivar Raw® 18 Kairi Sane Raw® 19 Kevin Owens Raw® 20 Lana Raw® 21 Liv Morgan Raw® 22 Montez Ford Raw® 23 Nia Jax Raw® 24 R-Truth Raw® 25 Randy Orton Raw® 26 Rezar Raw® 27 Ricochet Raw® 28 Riddick Moss Raw® 29 Ruby Riott Raw® 30 Samoa Joe Raw® 31 Seth Rollins Raw® 32 Shayna Baszler Raw® 33 Zelina Vega Raw® 34 AJ Styles SmackDown® 35 Alexa Bliss SmackDown® 36 Bayley SmackDown® 37 Big E SmackDown® 38 Braun Strowman SmackDown® 39 "The Fiend" Bray Wyatt SmackDown® 40 Carmella SmackDown® 41 Cesaro SmackDown® 42 Daniel Bryan SmackDown® 43 Dolph Ziggler SmackDown® 44 Elias SmackDown® 45 Jeff Hardy SmackDown® 46 Jey Uso SmackDown® 47 Jimmy Uso SmackDown® 48 John Morrison SmackDown® 49 King Corbin SmackDown® 50 Kofi Kingston SmackDown® 51 Lacey Evans SmackDown® 52 Mandy Rose SmackDown® 53 Matt Riddle SmackDown® 54 Mojo Rawley SmackDown® 55 Mustafa Ali Raw® 56 Naomi SmackDown® 57 Nikki Cross SmackDown® 58 Otis SmackDown® 59 Robert Roode Raw® 60 Roman Reigns SmackDown® 61 Sami Zayn SmackDown® 62 Sasha Banks SmackDown® 63 Sheamus SmackDown® 64 Shinsuke Nakamura SmackDown® 65 Shorty G SmackDown® 66 Sonya Deville SmackDown® 67 Tamina SmackDown® 68 The Miz SmackDown® 69 Tucker SmackDown® 70 Xavier Woods SmackDown® 71 Adam Cole NXT® 72 Bobby -

2021 Topps WWE NXT Checklist.Xls

BASE BASE CARDS 1 Roderick Strong™ def. Bronson Reed™ NXT 2 Keith Lee™ Retains the NXT® North American Championship NXT TakeOver: Portland 3 The BroserWeights™ Win the NXT® Tag Team Championship NXT TakeOver: Portland 4 NXT® Champion Adam Cole™ def. Tommaso Ciampa™ NXT TakeOver: Portland 5 Johnny Gargano™ Attacks Tommaso Ciampa™ NXT 6 The BroserWeights™ Retain the NXT® Tag Team Championship NXT 7 Tommaso Ciampa™ and Johnny Gargano™ Brawl in the WWE® PC NXT 8 Keith Lee™ def. Dominik Dijakovic™ and Damian Priest™ NXT 9 Johnny Gargano™ def. Tommaso Ciampa™ NXT 10 Timothy Thatcher™ Fills in for The BroserWeights™ NXT 11 Karrion Kross™ Attacks Tommaso Ciampa™ NXT 12 Akira Tozawa™ def. Isaiah "Swerve" Scott™ NXT 13 El Hijo del Fantasma™ Debuts NXT 14 Jake Atlas™ def. Drake Maverick™ NXT 15 Kushida™ def. Tony Nese™ NXT 16 Isaiah "Swerve" Scott™ def. El Hijo del Fantasma™ NXT 17 Imperium™ Attacks Matt Riddle™ & Timothy Thatcher™ NXT 18 Drake Maverick™ def. Tony Nese™ NXT 19 NXT® North American Champion Keith Lee™ def. Damian Priest™ NXT 20 Johnny Gargano™ def. Dominik Dijakovic™ NXT 21 Karrion Kross™ def. Leon Ruff™ NXT 22 Adam Cole™ Retains the NXT® Championship NXT 23 Akira Tozawa™ Picks up a Tournament Victory NXT 24 Kushida™ def. Jake Atlas™ NXT 25 Jake Atlas™ def. Tony Nese™ NXT 26 Imperium™ Wins the NXT® Tag Team Championship NXT 27 Damian Priest™ Attacks Finn Bálor™ NXT 28 Riddle™ def. Timothy Thatcher™ NXT 29 El Hijo del Fantasma™ Wins Group B NXT 30 Roderick Strong™ def. Dexter Lumis™ NXT 31 Drake Maverick™ Wins Group A NXT 32 Tommaso Ciampa™ def. -

It All Begins with Glass

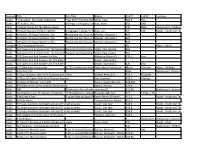

film festival guide IT ALL BEGINS WITH GLASS The selection of a lens is the moment that can defi ne a shoot. From Hollywood studios to exotic locations around the globe, amazing big screen content is dramatized every day through the selection of Canon cinema lenses. The technologies behind our PL and EF mount cinema lenses ensure clear, crisp motion capture to the most demanding shoots. Canon optics empower fi lmmakers to bring visions to life. Throughout the more than 75 years of Canon history, it’s why we’ve always placed Glass First. glassfi rst.com GLASS FIRST © 2015 Canon U.S.A., Inc. All rights reserved. Canon is a registered trademark of Canon Inc. in the United States and may also be a registered trademark or trademark in other countries. Canon_Glass First Ad_CINEQUEST 2016.indd 1 1/7/16 3:03 PM WELCOME unite at Film Festival! Join forces with eye in the sky artists, film lovers, and innova- pg 7 tors—from across the globe, from all walks of life. Experience the com- pelling power of ONE, through films, media innovations, events, and celebrations. Embrace old friend- james franco ships, create new pg 17 connections, band together. Radiate outward, forging original pathways into the future. Emerge as a close-knit community, bound by fresh and fortified fellowship, collaboration, inspiration, vision, rita moreno and creativity. Come together…Unite! pg 25 CINEQUEST FILM FESTIVAL 2016 MARCH 1 - 13 CINEQUEST FILM FESTIVAL PICTURE THE POSSIBILITIES CINEQUEST MAVERICKS STUDIO showcases premiere films, empowers global youth with the creates innovative and renowned and emerging artists, tools, confidence, and inspiration motion pictures, television, and and breakthrough technology— to form and create their dreams distribution paradigms. -

Ne Yo in My Own Words Download Zip

Ne Yo In My Own Words Download Zip 1 / 4 Ne Yo In My Own Words Download Zip 2 / 4 3 / 4 Check out this debut album from Ne-Yo titled In My Own Words. Released on February 28, 2006 by Def Jam Records. Listen now online.. Playlist · 25 Songs — You can't front on Ne-Yo's songwriting skills. ... and Mario, but he declared his solo ambitions with 2006's In My Own Words debut album.. Ne Yo In My Own Words.zip download from FileCrop.com, ... iTunes -Ne-Yo-In My Own Words (Deluxe Version)-(2006) ... Ne-Yo - R.E.D. (Japan iTunes Deluxe .... [Album] NE-YO – In My Own Words. 1st Full-Length Album. Released: ... Peedi Peedi] DOWNLOAD FULL ALBUM · Email ThisBlogThis!. Download zip, rar. Is there a 4-letter-word album title? Im sure there are many but some examples are. Flow: from the band Foetus. Bath: from the band maudlin .... In My Own Words. Ne-Yo. 12 tracks. Released in 2006. Hip Hop. Download album. Tracklist. 01. Stay. 02. Let Me Get This Right. 03. So Sick. 04. When You're .... After writing songs for artists like Mario, Chris Brown and Christina Milian, R&B prodigy Ne-Yo is stepping out on his own with this week's .... Listen free to Ne-Yo – In My Own Words (Let Me Get This Right (Album Version), So Sick (Album Version) and more). 10 tracks (36:59). Discover more music .... In My Own Words is the debut album from American singer-songwriter Ne-Yo, released on February 28, 2006. -

Resource Typeitle Sub-Title Author Call #1 Call #2 Location Books

Resource TitleType Sub-Title Author Call #1 Call #2 Location Books "Impossible" Marriages Redeemed They Didn't End the StoryMiller, in the MiddleLeila 265.5 MIL Books "R" Father, The 14 Ways To Respond To TheHart, Lord's Mark Prayer 242 HAR DVDs 10 Bible Stories for the Whole Family JUV Bible Audiovisual - Children's Books 10 Good Reasons To Be A Catholic A Teenager's Guide To TheAuer, Church Jim. Y/T 239 Books - Youth and Teen Books 10 Habits Of Happy Mothers, The Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose,Meeker, AndMargaret Sanity J. 649 Books 10 Habits Of Happy Mothers, The Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose,Meeker, AndMargaret Sanity J. 649 Books 10 Habits Of Happy Mothers, The Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose,Meeker, AndMargaret Sanity J. 649 Compact Discs100 Inspirational Hymns CD Music - Adult Books 101 Questions & Answers On The SacramentsPenance Of Healing And Anointing OfKeller, The Sick Paul Jerome 265 Books 101 Questions & Answers On The SacramentsPenance Of Healing And Anointing OfKeller, The Sick Paul Jerome 265 Books 101 Questions And Answers On Paul Witherup, Ronald D. 235.2 Paul Compact Discs101 Questions And Answers On The Bible Brown, Raymond E. Books 101 Questions And Answers On The Bible Brown, Raymond E. 220 BRO Compact Discs120 Bible Sing-Along songs & 120 Activities for Kids! Twin Sisters Productions Music Children Music - Children DVDs 13th Day, The DVD Audiovisual - Movies Books 15 days of prayer with Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton McNeil, Betty Ann 235.2 Elizabeth Books 15 Days Of Prayer With Saint Thomas Aquinas Vrai, Suzanne. -

Song List - Sorted by Song

Last Update 2/10/2007 Encore Entertainment PO Box 1218, Groton, MA 01450-3218 800-424-6522 [email protected] www.encoresound.com Song List - Sorted By Song SONG ARTIST ALBUM FORMAT #1 Nelly Nellyville CD #34 Matthews, Dave Dave Matthews - Under The Table And Dreamin CD #9 Dream Lennon, John John Lennon Collection CD (Every Time I Hear)That Mellow Saxophone Setzer Brian Swing This Baby CD (Sittin' On)The Dock Of The Bay Bolton, Michael The Hunger CD (You Make Me Feel Like A) Natural Woman Clarkson, Kelly American Idol - Greatest Moments CD 1 Thing Amerie NOW 19 CD 1, 2 Step Ciara (featuring Missy Elliott) Totally Hits 2005 CD 1,2,3 Estefan, Gloria Gloria Estafan - Greatest Hits CD 100 Years Blues Traveler Blues Traveler CD 100 Years Five For Fighting NOW 15 CD 100% Pure Love Waters, Crystal Dance Mix USA Vol.3 CD 11 Months And 29 Days Paycheck, Johnny Johnny Paycheck - Biggest Hits CD 1-2-3 Barry, Len Billboard Rock 'N' Roll Hits 1965 CD 1-2-3 Barry, Len More 60s Jukebox Favorites CD 1-2-3 Barry, Len Vintage Music 7 & 8 CD 14 Years Guns 'N' Roses Use Your Illusion II CD 16 Candles Crests, The Billboard Rock 'N' Roll Hits 1959 CD 16 Candles Crests, The Lovin' Fifties CD 16 Horses Soul Coughing X-Files - Soundtrack CD 18 Wheeler Pink Pink - Missundaztood CD 19 Paul Hardcastle Living In Oblivion Vol.1 CD 1979 Smashing Pumpkins 1997 Grammy Nominees CD 1982 Travis, Randy Country Jukebox CD 1982 Travis, Randy Randy Travis - Greatest Hits Vol.1 CD 1985 Bowlling For Soup NOW 17 CD 1990 Medley Mix Abdul, Paula Shut Up And Dance CD 1999 Prince -

British Wrestling Dvds Classic British Wrestling

BRITISH WRESTLING DVDS WWW.BRITISHWRESTLINGDVDS.VZE.COM For Any Enquiries, Please Email Me At [email protected] ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- CLASSIC BRITISH WRESTLING Hello again, grapple fans. Good afternoon to you and welcome to the 'Classic British Wrestling' section. Kent Walton introduces classic bouts featuring classic wrestlers from all over the UK. This section has now been updated with match locations and dates. In most cases, the dates shown are air dates, rather than the dates they were taped. CLASSIC BRITISH WRESTLING VOL 1 1. Kendo Nagasaki & Blondie Barratt vs. Robbie Brookside & Steve Regal (Bedworth, 15/10/1988) 2. Brian Maxine vs. Lucky Gordon (Bedworth, 15/10/1988) 3. Big Daddy & Tom Thumb vs. Drew McDonald & Sid Cooper (Everton, 2/7/1988) 4. Mel Stuart vs. Greg Valentine (Everton, 9/7/1988) 5. Bill Pearl vs. Greg Valentine (Nottingham, 18/7/1987) 6. Catweazle vs. Ian Wilson (Catford, 11/7/1987) 7. Sid Cooper & Zoltan Boscik vs. Jeff Kerry & Pete Collins (Broxbourne, 6/6/1987) 8. Pat Patton & Greg Valentine vs. Kurt & Karl Heinz (Broxbourne, 6/6/1987) 9. Sid Cooper & Zoltan Boscik vs. Greg Valentine & Pat Patton (Broxbourne, 6/6/1987) 10. Giant Haystacks vs. Jamaica George (Adwick Le Street, 20/6/1987) 11. Terry Rudge vs. Bully Boy Muir (Dartford, 27/8/1988) 12. Big Daddy & Pat Patton vs. Rasputin & Anaconda (Dartford, 27/8/1988) 13. Greg Valentine vs. Mr X (Dartford, 3/9/1988) 14. Giant Haystacks & King Kong Kirk vs. Marty Jones & Steve Logan (Nottingham, 25/7/1987) 15. Kid McCoy vs. Blackjack Mulligan (Burnley, 16/4/1988) 16. -

1 What Happened to Me in My Own Words Natalie Wallington All I Remember Is White Light. I Was Leaning Forward in Seat

1 What Happened To Me In My Own Words Natalie Wallington All I remember is white light. I was leaning forward in seat 23C (on the aisle) of the airplane bound for my semester at an international high school in Oman, drumming my fingers, worrying about how the toilets there are just a hole in the floor. Then there was a rumbling sound and my vision went white, and then I heard nothing. And I felt nothing. And then the water was all around me, up to my chin like an iron lung. I want to be really clear about this, because people always ask. The plane was quiet, and the cabin lights were on, and the temperature was maybe a little cool but nothing out of the ordinary. Every seat was full, as far as I could tell. A woman and her baby were sleeping next to me, and across the aisle a couple of businessmen were sharing candy out of a shiny box. Nobody looked angry or antsy or threatening at all. The rumbling I heard wasn’t mechanical, it was more like thunder. I didn’t even notice it until it was loud enough to notice, and then everything was completely gone. I opened my eyes and I was floating in the ocean, and I have no idea how much time passed in between. There was nothing. No severed airplane wings, no smoking metal carcass sinking into the waves, no floating suitcases. I was too shocked at first to even be cold. Then I yelled, and the sound that came out barely reached my own ears, let alone anyone else who could have been floating somewhere out of sight. -

2020 Topps WWE Finest Wrestling Checklist

BASE BASE CARDS 1 Angel Garza Raw® 2 Akam Raw® 3 Aleister Black Raw® 4 Andrade Raw® 5 Angelo Dawkins Raw® 6 Asuka Raw® 7 Austin Theory Raw® 8 Becky Lynch Raw® 9 Bianca Belair Raw® 10 Bobby Lashley Raw® 11 Murphy Raw® 12 Charlotte Flair Raw® 13 Drew McIntyre Raw® 14 Edge Raw® 15 Erik Raw® 16 Humberto Carrillo Raw® 17 Ivar Raw® 18 Kairi Sane Raw® 19 Kevin Owens Raw® 20 Lana Raw® 21 Liv Morgan Raw® 22 Montez Ford Raw® 23 Nia Jax Raw® 24 R-Truth Raw® 25 Randy Orton Raw® 26 Rezar Raw® 27 Ricochet Raw® 28 Riddick Moss Raw® 29 Ruby Riott Raw® 30 Samoa Joe Raw® 31 Seth Rollins Raw® 32 Shayna Baszler Raw® 33 Zelina Vega Raw® 34 AJ Styles SmackDown® 35 Alexa Bliss SmackDown® 36 Bayley SmackDown® 37 Big E SmackDown® 38 Braun Strowman SmackDown® 39 "The Fiend" Bray Wyatt SmackDown® 40 Carmella SmackDown® 41 Cesaro SmackDown® 42 Daniel Bryan SmackDown® 43 Dolph Ziggler SmackDown® 44 Elias SmackDown® 45 Jeff Hardy SmackDown® 46 Jey Uso SmackDown® 47 Jimmy Uso SmackDown® 48 John Morrison SmackDown® 49 King Corbin SmackDown® 50 Kofi Kingston SmackDown® 51 Lacey Evans SmackDown® 52 Mandy Rose SmackDown® 53 Matt Riddle SmackDown® 54 Mojo Rawley SmackDown® 55 Mustafa Ali Raw® 56 Naomi SmackDown® 57 Nikki Cross SmackDown® 58 Otis SmackDown® 59 Robert Roode Raw® 60 Roman Reigns SmackDown® 61 Sami Zayn SmackDown® 62 Sasha Banks SmackDown® 63 Sheamus SmackDown® 64 Shinsuke Nakamura SmackDown® 65 Shorty G SmackDown® 66 Sonya Deville SmackDown® 67 Tamina SmackDown® 68 The Miz SmackDown® 69 Tucker SmackDown® 70 Xavier Woods SmackDown® 71 Adam Cole NXT® 72 Bobby -

Ne Yo R.E.D Album Download Zip Ne Yo R.E.D Album Download Zip

ne yo r.e.d album download zip Ne yo r.e.d album download zip. Download working: Ne-yo Good Man Full direct album, free link, hq zip tracks. Good Man (stylized in all caps) is the seventh studio album by American singer Ne-Yo. The album was released on June 8, 2018, by Motown Records. Ne-Yo chooses the second path, presumably hoping to sneak his records into mix-show play on the radio. Good Man is loaded with standard-issue rap/R&B hybrids, in which the singer floats his flexible voice over beats that grind and crack – “L.A. Nights,” “Breathe,” “Back Chapters,” “Over U.” The other major component of Good Man, more interesting if not more convincing, is a dollop of pan-Caribbean rhythms. Ne-Yo fares best on “Without U,” which wouldn’t be out of place in a DJ set containing Nicky Jam and J Balvin’s “X.” With more zip in the beat, the singer’s winning airiness returns. But then comes “Apology,” a return to the trap sound, and once again, a heavy beat suppresses Ne-Yo’s gliding verve. It’s an old story: In his hunt for a hit, Ne-Yo ended up discarding much of what initially set him apart. Year: 2018 Genre: R’n’B. 01. Ne-Yo – “Caterpillars 1st” (INTRO) (0:41) 02. Ne-Yo – 1 More Shot (3:50) 03. Ne-Yo – LA NIGHTS (3:54) 04. Ne-Yo – Nights Like These (feat. Romeo Santos) (3:24) 05. Ne-Yo – U Deserve (3:44) 06.