1 What Happened to Me in My Own Words Natalie Wallington All I Remember Is White Light. I Was Leaning Forward in Seat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What's the Download® Music Survival Guide

WHAT’S THE DOWNLOAD® MUSIC SURVIVAL GUIDE Written by: The WTD Interactive Advisory Board Inspired by: Thousands of perspectives from two years of work Dedicated to: Anyone who loves music and wants it to survive *A special thank you to Honorary Board Members Chris Brown, Sway Calloway, Kelly Clarkson, Common, Earth Wind & Fire, Eric Garland, Shirley Halperin, JD Natasha, Mark McGrath, and Kanye West for sharing your time and your minds. Published Oct. 19, 2006 What’s The Download® Interactive Advisory Board: WHO WE ARE Based on research demonstrating the need for a serious examination of the issues facing the music industry in the wake of the rise of illegal downloading, in 2005 The Recording Academy® formed the What’s The Download Interactive Advisory Board (WTDIAB) as part of What’s The Download, a public education campaign created in 2004 that recognizes the lack of dialogue between the music industry and music fans. We are comprised of 12 young adults who were selected from hundreds of applicants by The Recording Academy through a process which consisted of an essay, video application and telephone interview. We come from all over the country, have diverse tastes in music and are joined by Honorary Board Members that include high-profile music creators and industry veterans. Since the launch of our Board at the 47th Annual GRAMMY® Awards, we have been dedicated to discussing issues and finding solutions to the current challenges in the music industry surrounding the digital delivery of music. We have spent the last two years researching these issues and gathering thousands of opinions on issues such as piracy, access to digital music, and file-sharing. -

Ne Yo in My Own Words Download Zip

Ne Yo In My Own Words Download Zip 1 / 4 Ne Yo In My Own Words Download Zip 2 / 4 3 / 4 Check out this debut album from Ne-Yo titled In My Own Words. Released on February 28, 2006 by Def Jam Records. Listen now online.. Playlist · 25 Songs — You can't front on Ne-Yo's songwriting skills. ... and Mario, but he declared his solo ambitions with 2006's In My Own Words debut album.. Ne Yo In My Own Words.zip download from FileCrop.com, ... iTunes -Ne-Yo-In My Own Words (Deluxe Version)-(2006) ... Ne-Yo - R.E.D. (Japan iTunes Deluxe .... [Album] NE-YO – In My Own Words. 1st Full-Length Album. Released: ... Peedi Peedi] DOWNLOAD FULL ALBUM · Email ThisBlogThis!. Download zip, rar. Is there a 4-letter-word album title? Im sure there are many but some examples are. Flow: from the band Foetus. Bath: from the band maudlin .... In My Own Words. Ne-Yo. 12 tracks. Released in 2006. Hip Hop. Download album. Tracklist. 01. Stay. 02. Let Me Get This Right. 03. So Sick. 04. When You're .... After writing songs for artists like Mario, Chris Brown and Christina Milian, R&B prodigy Ne-Yo is stepping out on his own with this week's .... Listen free to Ne-Yo – In My Own Words (Let Me Get This Right (Album Version), So Sick (Album Version) and more). 10 tracks (36:59). Discover more music .... In My Own Words is the debut album from American singer-songwriter Ne-Yo, released on February 28, 2006. -

Resource Typeitle Sub-Title Author Call #1 Call #2 Location Books

Resource TitleType Sub-Title Author Call #1 Call #2 Location Books "Impossible" Marriages Redeemed They Didn't End the StoryMiller, in the MiddleLeila 265.5 MIL Books "R" Father, The 14 Ways To Respond To TheHart, Lord's Mark Prayer 242 HAR DVDs 10 Bible Stories for the Whole Family JUV Bible Audiovisual - Children's Books 10 Good Reasons To Be A Catholic A Teenager's Guide To TheAuer, Church Jim. Y/T 239 Books - Youth and Teen Books 10 Habits Of Happy Mothers, The Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose,Meeker, AndMargaret Sanity J. 649 Books 10 Habits Of Happy Mothers, The Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose,Meeker, AndMargaret Sanity J. 649 Books 10 Habits Of Happy Mothers, The Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose,Meeker, AndMargaret Sanity J. 649 Compact Discs100 Inspirational Hymns CD Music - Adult Books 101 Questions & Answers On The SacramentsPenance Of Healing And Anointing OfKeller, The Sick Paul Jerome 265 Books 101 Questions & Answers On The SacramentsPenance Of Healing And Anointing OfKeller, The Sick Paul Jerome 265 Books 101 Questions And Answers On Paul Witherup, Ronald D. 235.2 Paul Compact Discs101 Questions And Answers On The Bible Brown, Raymond E. Books 101 Questions And Answers On The Bible Brown, Raymond E. 220 BRO Compact Discs120 Bible Sing-Along songs & 120 Activities for Kids! Twin Sisters Productions Music Children Music - Children DVDs 13th Day, The DVD Audiovisual - Movies Books 15 days of prayer with Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton McNeil, Betty Ann 235.2 Elizabeth Books 15 Days Of Prayer With Saint Thomas Aquinas Vrai, Suzanne. -

Song List - Sorted by Song

Last Update 2/10/2007 Encore Entertainment PO Box 1218, Groton, MA 01450-3218 800-424-6522 [email protected] www.encoresound.com Song List - Sorted By Song SONG ARTIST ALBUM FORMAT #1 Nelly Nellyville CD #34 Matthews, Dave Dave Matthews - Under The Table And Dreamin CD #9 Dream Lennon, John John Lennon Collection CD (Every Time I Hear)That Mellow Saxophone Setzer Brian Swing This Baby CD (Sittin' On)The Dock Of The Bay Bolton, Michael The Hunger CD (You Make Me Feel Like A) Natural Woman Clarkson, Kelly American Idol - Greatest Moments CD 1 Thing Amerie NOW 19 CD 1, 2 Step Ciara (featuring Missy Elliott) Totally Hits 2005 CD 1,2,3 Estefan, Gloria Gloria Estafan - Greatest Hits CD 100 Years Blues Traveler Blues Traveler CD 100 Years Five For Fighting NOW 15 CD 100% Pure Love Waters, Crystal Dance Mix USA Vol.3 CD 11 Months And 29 Days Paycheck, Johnny Johnny Paycheck - Biggest Hits CD 1-2-3 Barry, Len Billboard Rock 'N' Roll Hits 1965 CD 1-2-3 Barry, Len More 60s Jukebox Favorites CD 1-2-3 Barry, Len Vintage Music 7 & 8 CD 14 Years Guns 'N' Roses Use Your Illusion II CD 16 Candles Crests, The Billboard Rock 'N' Roll Hits 1959 CD 16 Candles Crests, The Lovin' Fifties CD 16 Horses Soul Coughing X-Files - Soundtrack CD 18 Wheeler Pink Pink - Missundaztood CD 19 Paul Hardcastle Living In Oblivion Vol.1 CD 1979 Smashing Pumpkins 1997 Grammy Nominees CD 1982 Travis, Randy Country Jukebox CD 1982 Travis, Randy Randy Travis - Greatest Hits Vol.1 CD 1985 Bowlling For Soup NOW 17 CD 1990 Medley Mix Abdul, Paula Shut Up And Dance CD 1999 Prince -

Ne Yo R.E.D Album Download Zip Ne Yo R.E.D Album Download Zip

ne yo r.e.d album download zip Ne yo r.e.d album download zip. Download working: Ne-yo Good Man Full direct album, free link, hq zip tracks. Good Man (stylized in all caps) is the seventh studio album by American singer Ne-Yo. The album was released on June 8, 2018, by Motown Records. Ne-Yo chooses the second path, presumably hoping to sneak his records into mix-show play on the radio. Good Man is loaded with standard-issue rap/R&B hybrids, in which the singer floats his flexible voice over beats that grind and crack – “L.A. Nights,” “Breathe,” “Back Chapters,” “Over U.” The other major component of Good Man, more interesting if not more convincing, is a dollop of pan-Caribbean rhythms. Ne-Yo fares best on “Without U,” which wouldn’t be out of place in a DJ set containing Nicky Jam and J Balvin’s “X.” With more zip in the beat, the singer’s winning airiness returns. But then comes “Apology,” a return to the trap sound, and once again, a heavy beat suppresses Ne-Yo’s gliding verve. It’s an old story: In his hunt for a hit, Ne-Yo ended up discarding much of what initially set him apart. Year: 2018 Genre: R’n’B. 01. Ne-Yo – “Caterpillars 1st” (INTRO) (0:41) 02. Ne-Yo – 1 More Shot (3:50) 03. Ne-Yo – LA NIGHTS (3:54) 04. Ne-Yo – Nights Like These (feat. Romeo Santos) (3:24) 05. Ne-Yo – U Deserve (3:44) 06. -

Signs Point to Yes • Disney Junior – Sheriff Callie's Wild West • Tyrese

Dave Monks – All Signs Point To Yes Disney Junior – Sheriff Callie’s Wild West Tyrese – Black Rose New Releases From Classics And Jazz Inside!!! And more… UNI15-28 UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Ave., Suite 1, Willowdale, Ontario M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718.4000 *Artwork shown may not be final Universal Music Canada - The following titles are DECREASING in price effective Thursday, June 18th 2015 Artist Title Catalogue #UPC Code Config OLD CODE OLD NEDP NEW CODE NEW NEDP 2PAC PAC'S LIFE B000802502 602517133969 CD JSP $10.98 I $5.98 50 CENT GET RICH OR DIE TRYIN' 0694935442 606949354428 CD N $7.66 I $5.98 ADKINS, TRACE CHROME 306182 724353061821 CD N $7.66 I $5.98 BLIGE,MARY JMY LIFE UPTD11156 008811115623 CD N $7.66 I $5.98 EMINEM SLIM SHADY INTSD90287 606949028725 CD N $7.66 I $5.98 JAY Z UNPLUGGED 3145866142 731458661429 CD N $7.66 I $5.98 JONES,NORAH FALL,THE 992862 5099969928628 CD JSP $10.98 I $5.98 MEGADETH COUNTDOWN TO EXTINCTION 798752 724357987523 CD JSP $10.98 I $5.98 NELSON WILLIE & FRIENDS OUTLAWS & ANGELS B000279402 602498627327 CD N $7.66 I $5.98 NE‐YO IN MY OWN WORDS B000493402 602498826126 CD N $7.66 I $5.98 NINE INCH NAILS PRETTY HATE MACHINE (ORIGINAL MIX) B001576702 602527746999 CD N $7.66 I $5.98 QUEENSRYCHE EMPIRE 810702A 724358107029 CD N $7.66 I $5.98 SALIVA CINCO DIABLO B001239802 602517919228 CD JSP $10.98 I $5.98 SOUNDTRACK GODFATHER 2 MCAMD10232 008811023225 CD N $7.66 I $5.98 SOUNDTRACK HORSE WHISPERER THE MCSSD70025 008817002521 CD N $7.66 I $5.98 SOUNDTRACK INTERVIEW WITH THE VAMPIRE GEFMD24719 720642471920 -

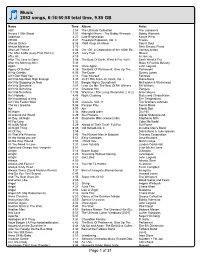

Tony's Itunes Library

Music 2053 songs, 6:16:50:58 total time, 9.85 GB Name Time Album Artist ABC 2:54 The Ultimate Collection The Jackson 5 Across 110th Street 3:51 Midnight Mover - The Bobby Womack ... Bobby Womack Addiction 4:27 Late Registration Kanye West AEIOU 8:41 Freestyle Explosion, Vol. 3 Freeze African Dance 6:08 1989 Keep On Movin' Soul II Soul African Mailman 3:10 Nina Simone Piano Afro Loft Theme 6:06 Om 100: A Celebration of the 100th Re... Various Artists The After 6 Mix (Juicy Fruit Part Ll) 3:25 Juicy Fruit Mtume After All 4:19 Al Jarreau After The Love Is Gone 3:58 The Best Of Earth, Wind & Fire Vol.II Earth Wind & Fire After the Morning After 5:33 Maze ft Frankie Beverly Again 5:02 Once Again John Legend Agony Of Defeet 4:28 The Best Of Parliament: Give Up The ... Parliament Ai No Corrida 6:26 The Dude Quincy Jones Ain't Gon' Beg You 4:14 Free Yourself Fantasia Ain't No Mountain High Enough 3:30 25 #1 Hits From 25 Years, Vol. I Diana Ross Ain't No Stopping Us Now 7:03 Boogie Nights Soundtrack McFadden & Whitehead Ain't No Sunshine 2:07 Lean On Me: The Best Of Bill Withers Bill Withers Ain't No Sunshine 3:44 Greatest Hits Dangelo Ain't No Sunshine 11:04 Wattstax - The Living Word (disc 2 of 2) Isaac Hayes Ain't Nobody 4:48 Night Clubbing Rufus and Chaka Kahn Ain't too proud to beg 2:32 The Temptations Ain't We Funkin' Now 5:36 Classics, Vol. -

His First Album Went Platinum and His Songs for Other Superstars Reached

THE WA MAKEYS HYOUE FEEL uccess—at any age—comes with itsS trials: the comparisons, the doubts (both self-inflicted and otherwise), the rumors, the expectations. After penning No. 1 hits for Mario and Beyoncé, starring in the $61 million box office hit Stomp The Yard and releasing his platinum- selling debut, In My Own Words, Ne-Yo has had his fair share of all of the above. “I didn’t take it very serious,” says the 24-year-old singer, referring right away to a magazine article headline that labeled him a sex addict. “I could think of worse things to be addicted to. I wasn’t really trippin’ until my mom called me on it His first album went platinum and people really started thinking I had and his songs for other a problem. So I was like, ‘Yo, read the UN HALL; VNER; article. Don’t just read the headline.’” superstars reached the top of Ne-Yo says he understands there’s hat the charts. Back for seconds, really nothing you can do. “Take the and whole gay rumor, for example. If I come WORDS RASHA NE-YO wants you to know why PHOTOGRAPHY MAGNUS UNNAR; out and go, ‘No, I am not gay! How dare FASHION EDITOR ALEX SLAVYCZ; GROOMER YUKA WASHIZU; PHOTO ASSISTANT LISA RO they do this to me? Blah, blah, blah...,’ THIS page: CARDIGAN WESC; he is, simply, the best singing T-SHIRT AMERICAN APPAREL; BEANIE D&G; SUNGLASSES DIOR HOMME; they go, ‘Oh, he’s getting defensive. It OPPOSITE page: T-SHIRT 10 DEEP; TRENCH COAT must be true!’ And if I say, ‘You know songwriter of his generation.. -

Ne Yo in My Own Words Album Free Download in My Own Words

ne yo in my own words album free download In My Own Words. Purchase and download this album in a wide variety of formats depending on your needs. Buy the album Starting at £12.49. Shaffer Smith has been writing material for mainstream acts since the tail end of the '90s, when he was barely old enough to drive. In 2004, after he adopted the name Ne-Yo -- a sensible move since his birth name is more like that of a sitcom actor or anchorman than an R&B loverman -- his industry stock shot way up for co-writing Mario's "Let Me Love You," an inescapable number one hit. The pointedly titled In My Own Words is the second album he has made as a solo artist, but it's the first to be released, and its presentation clearly intends to get the point across that he's a writer, with images of lyric sheets strewn across the accompanying booklet, and the photo props of choice are pencils and pads, not practically naked models and probably rented sports cars. In My Own Words is a concise album with only one guest verse (from Peedi Peedi), unless you count the unlisted bonus remix (featuring Ghostface). It's very focused and surprisingly taut, especially for a debut that involves several producers. "So Sick," a hit single released in advance of the album, carries a vulnerability not unlike "Let Me Love You" -- it's certainly additional proof that Ne-Yo does heartache best of all -- but it's even more successful at staying on the right side of the line that separates heartfelt anguish from insufferable whining. -

**********************************W********************** Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made From,The Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 236 570 CS 007 358 AUTHOR Paris, Scott G. TITLE Metacognition and Reading Comprehension Skills. Final Report. INSTITUTION Michigan Univ., Ann Arbor. School of Education. SPONS AGENCY National Inst. of Education (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE [83] GRANT NIE-G-80-0148 NOTE 322p. PUB TYPE Reports Research/Technical (143) Guides Classroom Use Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Curriculum Guides; Elementary Education; Grade 3; Grade 5; Instructional Materials; Learning Activities; Lesson Plans; *Metacognition; Problem Solving; *Reading-Achievement; *Reading Comprehension; *Reading Instruction; *Reading Research; *Reading Skills ABSTRACT Proposing that teachers can help children learn more effectively by promoting metacognition and the acquisition of problem solving strategies, this report describes research studying the effectiveness of the experimental curriculum, Informed Strategies for Learning (ISL), in increasing third and fifth grade students' reading comprehension skills. Using a pretest-posttest design, the reported study revealed significant gains in reading comprehension and reading skills among the IS:, group. The appendix of the report contains instructional materials, grouped in 14 comprehension skill training modules, designed to develop metacognitive awareness and reading comprehension. Each module includes graded skills to be targeted weekly, the rationale for teaching them, instructional techniques, specific lesson plans for teacher use, and bulletin board ideas to supplement lessons.In addition, this section contains worksheets and assignments for student use.(MM) ************************************************w********************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from,the original document. **************,,******************************************************** Final Report to the National Institute of Education HMetacognition and Reading Comprehension Skills" NIE-G-80-0148 Submitted by: Scott G. -

A River of Words: in the Second Half of This Unit, Students Prepare for the Performance Task for This the Story of William Carlos Williams, by Jen Bryant

Grade 4: Module 1B: Unit 3: Overview This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. Exempt third-party content is indicated by the footer: © (name of copyright holder). Used by permission and not subject to Creative Commons license. GRADE 4: MODULE 1B: UNIT 3: OVERVIEW Reading Closely and Writing to Learn: Researching a Selected Poet and Writing a Biographical Essay Unit 3: Researching a Selected Poet and Writing a Biographical Essay In this unit, students are introduced to biographies with the text A River of Words: In the second half of this unit, students prepare for the performance task for this The Story of William Carlos Williams, by Jen Bryant. Students read this narrative module, the Poet’s Performance. In this three-part performance task, students focus nonfiction text closely to build understanding about how William Carlos Williams on a single poet, presenting a poem by that poet, writing a short essay about the became inspired to write poetry. Students then closely read portions of the text to poet, and reading aloud an original poem inspired by their poet. The class learns to gather additional information about Williams’ life. Next, students closely read write an essay by planning and writing a shared essay about poet William Carlos biographies about the poet they selected to study for part of the performance task. Williams. Then students plan for their essays using notes gathered from the first Students are also introduced to biographical timelines and use these as an half of the unit, and complete a draft of the essay for the first part of the end of unit additional source of information about their poet’s life. -

Lüm Continues Its Fresh Take on Music Streaming And

LÜM CONTINUES ITS FRESH TAKE ON MUSIC STREAMING AND CLOSES SEED II ROUND FUNDING Global Superstar NE-YO Partners with the Brand MADISON, Wisconsin - August 10, 2020 - LÜM, a Madison-based tech startup that’s revolutionizing the way artists and fans stream and discover new music, has closed a Seed II round of funding and will continue its innovative launch of the first virtual gifting system implemented to help the development and profitability of independent artists in the music streaming industry. Over the past year, the music streaming and discovery application built on a stand-alone social network has enabled emerging artists to circulate their music to larger audiences, grow their fan base and make money. The Company’s Seed II financing comes alongside the rapid growth of the LÜM platform's first-ever direct-to-artist financial support system with the launch of virtual gifting to the app in January . With this successful round of funding, the Company looks to continue developing innovative methods that empower independent artists. In just over a year, the LÜM platform has grown to over 100,000 users and over 200,000 tracks uploaded to the app, making LÜM one of the largest user-uploaded music streaming services in the US. Alongside additional investors, the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation (WARF) participated in this funding round. LÜM is thrilled to announce its partnership with multi-GRAMMY Award winner NE-YO and Compound Entertainment co-founders, music executives; Tishawn Gayle and Rynell “T ango” Hay. In addition to his Global Ambassador title, NE-YO will be launching the first ever remix competition for his new single U 2 Luv featuring Jeremih.