Here Had Been Some Way of Returning Them to the Deep Water of the Open Ocean, but It Was Not Possible.”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Checklist of Fish and Invertebrates Listed in the CITES Appendices

JOINTS NATURE \=^ CONSERVATION COMMITTEE Checklist of fish and mvertebrates Usted in the CITES appendices JNCC REPORT (SSN0963-«OStl JOINT NATURE CONSERVATION COMMITTEE Report distribution Report Number: No. 238 Contract Number/JNCC project number: F7 1-12-332 Date received: 9 June 1995 Report tide: Checklist of fish and invertebrates listed in the CITES appendices Contract tide: Revised Checklists of CITES species database Contractor: World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge, CB3 ODL Comments: A further fish and invertebrate edition in the Checklist series begun by NCC in 1979, revised and brought up to date with current CITES listings Restrictions: Distribution: JNCC report collection 2 copies Nature Conservancy Council for England, HQ, Library 1 copy Scottish Natural Heritage, HQ, Library 1 copy Countryside Council for Wales, HQ, Library 1 copy A T Smail, Copyright Libraries Agent, 100 Euston Road, London, NWl 2HQ 5 copies British Library, Legal Deposit Office, Boston Spa, Wetherby, West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ 1 copy Chadwick-Healey Ltd, Cambridge Place, Cambridge, CB2 INR 1 copy BIOSIS UK, Garforth House, 54 Michlegate, York, YOl ILF 1 copy CITES Management and Scientific Authorities of EC Member States total 30 copies CITES Authorities, UK Dependencies total 13 copies CITES Secretariat 5 copies CITES Animals Committee chairman 1 copy European Commission DG Xl/D/2 1 copy World Conservation Monitoring Centre 20 copies TRAFFIC International 5 copies Animal Quarantine Station, Heathrow 1 copy Department of the Environment (GWD) 5 copies Foreign & Commonwealth Office (ESED) 1 copy HM Customs & Excise 3 copies M Bradley Taylor (ACPO) 1 copy ^\(\\ Joint Nature Conservation Committee Report No. -

Journal of Tropical Ecology the Role of Earthworms in Nitrogen and Solute

Journal of Tropical Ecology http://journals.cambridge.org/TRO Additional services for Journal of Tropical Ecology: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here The role of earthworms in nitrogen and solute retention in a tropical forest in Sabah, Malaysia: a pilot study Sarah Johnson, Arshiya Bose, Jake L. Snaddon and Brian Moss Journal of Tropical Ecology / Volume 28 / Issue 06 / November 2012, pp 611 614 DOI: 10.1017/S0266467412000624, Published online: Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0266467412000624 How to cite this article: Sarah Johnson, Arshiya Bose, Jake L. Snaddon and Brian Moss (2012). The role of earthworms in nitrogen and solute retention in a tropical forest in Sabah, Malaysia: a pilot study. Journal of Tropical Ecology, 28, pp 611614 doi:10.1017/ S0266467412000624 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/TRO, IP address: 138.253.100.121 on 28 Nov 2012 Journal of Tropical Ecology (2012) 28:611–614. © Cambridge University Press 2012 doi:10.1017/S0266467412000624 SHORT COMMUNICATION The role of earthworms in nitrogen and solute retention in a tropical forest in Sabah, Malaysia: a pilot study Sarah Johnson∗, Arshiya Bose†, Jake L. Snaddon‡ and Brian Moss§,1 ∗ School of Environment and Life Sciences, University of Salford, Salford, UK † School of Geography, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK ‡ Biodiversity Institute, Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, UK § School of Environmental Sciences, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK (Accepted 19 September 2012) Key Words: conductivity, Danum valley, nitrogen, nutrient recycling, Pheretima darnleiensis,soil Compounds of the 20 elements needed by living deep) and, by this modest physical recycling, decrease the organisms are relatively soluble in water and therefore risk of washout. -

Lecythidaceae (G.T

Flora Malesiana, Series I, Volume 21 (2013) 1–118 LECYTHIDACEAE (G.T. Prance, Kew & E.K. Kartawinata, Bogor)1 Lecythidaceae A.Rich. in Bory, Dict. Class. Hist. Nat. 9 (1825) 259 (‘Lécythidées’), nom. cons.; Poit., Mém. Mus. Hist. Nat. Paris 13 (1835) 141; Miers, Trans. Linn. Soc. London, Bot. 30, 2 (1874) 157; Nied. in Engl. & Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam. 3, 7 (1892) 30; R.Knuth in Engl., Pflanzenr. IV.219, Heft 105 (1939) 26; Whitmore, Tree Fl. Malaya 2 (1973) 257; R.J.F.Hend., Fl. Australia 8 (1982) 1; Corner, Wayside Trees Malaya ed. 3, 1 (1988) 349; S.A.Mori & Prance, Fl. Neotrop. Monogr. 21, 2 (1990) 1; Chantar., Kew Bull. 50 (1995) 677; Pinard, Tree Fl. Sabah & Sarawak 4 (2002) 101; H.N.Qin & Prance, Fl. China 13 (2007) 293; Prance in Kiew et al., Fl. Penins. Malaysia, Ser. 2, 3 (2012) 175. — Myrtaceae tribus Lecythideae (A.Rich.) A.Rich. ex DC., Prodr. 3 (1828) 288. — Myrtaceae subtribus Eulecythideae Benth. & Hook.f., Gen. Pl. 1, 2 (1865) 695, nom. inval. — Type: Lecythis Loefl. Napoleaeonaceae A.Rich. in Bory, Dict. Class. Hist. Nat. 11 (1827) 432. — Lecythi- daceae subfam. Napoleonoideae Nied. in Engl. & Prantl., Nat. Pflanzenfam. 3, 7 (1893) 33. — Type: Napoleonaea P.Beauv. Scytopetalaceae Engl. in Engl. & Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam., Nachtr. 1 (1897) 242. — Lecythidaceae subfam. Scytopetaloideae (Engl.) O.Appel, Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 121 (1996) 225. — Type: Scytopetalum Pierre ex Engl. Lecythidaceae subfam. Foetidioideae Nied. in Engl. & Prantl, Nat Pflanzenfam. 3, 7 (1892) 29. — Foetidiaceae (Nied.) Airy Shaw in Willis & Airy Shaw, Dict. Fl. Pl., ed. -

Body Painting Type Analysis Based on Biomimicry Camouflage

International Journal of Architecture, Arts and Applications 2020; 6(1): 1-11 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ijaaa doi: 10.11648/j.ijaaa.20200601.11 ISSN: 2472-1107 (Print); ISSN: 2472-1131 (Online) Review Article Body Painting Type Analysis Based on Biomimicry Camouflage Eun-Young Park Department of Bioengineering, Graduate School of Konkuk University, Seoul, South Korea Email address: To cite this article: Eun-Young Park. Body Painting Type Analysis Based on Biomimicry Camouflage. International Journal of Architecture, Arts and Applications. Vol. 6, No. 1, 2020, pp. 1-11. doi: 10.11648/j.ijaaa.20200601.11 Received: November 26, 2019; Accepted: December 20, 2019; Published: January 7, 2020 Abstract: The purpose of this study is to establish a method and find a possible way of applying biomimicry camouflage in body painting. This study seeks a direction for the future of the beauty and art industry through biomimicry. For this study, we analyzed the works by classifying camouflage body painting into passive and active camouflage sections based on the application of biomimicry to the artificial camouflage system. In terms of detailed types, passive camouflage was classified into general resemblance and special resemblance, and active camouflage into adventitious resemblance and variable protective resemblance, and expression characteristics and type were derived. Passive camouflage is the work of the pictorial expressive technique using aqueous and oily body painting products. The general resemblance was expressed as a body painting of crypsis and camouflage strategies. The special resemblance is a mimicry in which the human body camouflages the whole figure of living organisms or inanimate objects. -

Darwin's Earthworms (Annelida, Oligochaeta, Megadrilacea With

Opusc. Zool. Budapest, 2016, 47(1): 09–30 Darwin’s earthworms (Annelida, Oligochaeta, Megadrilacea) with review of cosmopolitan Metaphire peguana–species group from Philippines R.J. BLAKEMORE Robert J. Blakemore, VermEcology, Yokohama and C/- Lake Biwa Museum Shiga-ken, Japan. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. A chance visit to Darwin allowed inspection of and addition to Northern Territory (NT) Museum’s earthworm collection. Native Diplotrema zicsii sp. nov. from Alligator River, Kakadu NP is described. Town samples were dominated by cosmopolitan exotic Metaphire bahli (Gates, 1945) herein keyed and compared morpho-molecularly with M. peguana (Rosa, 1890) requiring revision of allied species including Filipino Pheretima philippina (Rosa, 1891), P. p. lipa and P. p. victorias sub-spp. nov. A new P. philippina-group now replaces the dubia-group of Sims & Easton, 1972 and Amynthas carinensis (Rosa, 1890) further replaces their sieboldi-group. Lumbricid Eisenia fetida (Savigny, 1826) and Glossoscolecid Pontoscolex corethrurus (Müller, 1857) are confirmed introductions to the NT. mtDNA barcodes newly include Metaphire houlleti (Perrier, 1872) and Polypheretima elongata (Perrier, 1872) spp.-complexes from the Philippines. Pithemera philippinensis James & Hong, 2004 and Pi. glandis Hong & James, 2011 are new synonyms of Pi. bicincta (Perrier, 1875) that is common in Luzon. Vietnamese homonym Pheretima thaii Nguyen, 2011 (non P. thaii Hong & James, 2011) is replaced with Pheretima baii nom. nov. Two new Filipino taxa are also described: Pleionogaster adya sp. nov. from southern Luzon and Pl. miagao sp. nov. from western Visayas. Keywords. Soil fauna, invertebrate biodiversity, new endemic taxa, mtDNA barcodes, Australia, EU. INTRODUCTION tion was of native Diplotrema eremia (Spencer, 1896) from Alice Springs, only a dozen natives iodiversity assessment is important to gauge and just 8 exotics reviewed 33 years ago by B natural resources and determine regional Easton (1982) then Blakemore (1994, 1999, 2002, changes. -

Montana Kaimin, October 11, 1979 Associated Students of the University of Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Associated Students of the University of Montana Montana Kaimin, 1898-present (ASUM) 10-11-1979 Montana Kaimin, October 11, 1979 Associated Students of the University of Montana Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper Recommended Citation Associated Students of the University of Montana, "Montana Kaimin, October 11, 1979" (1979). Montana Kaimin, 1898-present. 6865. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper/6865 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Associated Students of the University of Montana (ASUM) at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Montana Kaimin, 1898-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Common Cause chief blasts energy politics the bill for environmentally un By CATHY KRADOLFER that fluctuated between 25 and 75 and marketing of power in the power plant projects. As part of the Montana Kalmln Reporter persons attended the forum spon Pacific Northwest. Its ad agreement, the BPA would sound policies" such as strip sored by th.e Student Action ministrator is appointed by the guarantee that it would provide a mining and synthetic fuel produc Government agencies and of Center as part of the week-long president. market for the electricity produced tion. He charged that the Carter ad ficials are trying to "subvert" "Conference on the Environment." Senate Bill 885, which has pass by the plant. ministration's energy policy is citizen participation in energy ed the Senate and will soon be The legislation, Richards said, policy decisions, the state director Blasts BPA bill considered by the House of would give the BPA an "open door” backed by business interests such of Common Cause said in Richards said legislation before Representatives, will allow the to build more coal-fired generating as oil companies. -

The Stick-Insects of Great Britain, Ireland and the Channel Isles by Malcolm Lee, Gullrock, Port Gaverne, Port Isaac, Cornwall

The Phasmid Study Group SEPTEMBER 2006 NEWSLETTER No 107 This Newsletter looks fantastic ISSN 0268-3806 in full colour. Go to the members' area of the PSG INDEX Website to view &/or download. National Insect Week Page 5 Page Content The Colour Page Editorial, Diary Dates, PSG Committee Stick Talk National Insect Week Eurycantha calcarata Observations The Kettering Show, Phasmids in the News Respiration in Phasmids Collecting in Thailand, Additions to Culture list PSG Summer Meeting Plea for Comments on Future PSG Meetings Database of Natural History Museum in Vienna Word Scramble, New Editor Needed for Newsletter Defensive Tactics in Phasmids Report on Pestival Word Scramble Answers, Survey Results, PSG Merchandise, Wants & Exchanges, Members' Website Password, Helpful Taxonomists Wanted Stick Insects of Great Britain Phaenopharos khaoyaiensis Article , Obituary. PSG Summer Meeting, Page 11. Which is the ant, which the nymph? Page15. NOTICE It is to be directly understood that all views, opinions or theories, expressed in the pages of "The Newsletter", are those of the author(s) concerned. All announcements of meetings, requests for help or information, are accepted as bona fide. Neither the Editor, nor Officers and Committee of "The Phasmid Study Group", can be held responsible for any loss, embarrassment or injury that might be sustained by reliance thereon. September 2006 Website: www.stickinsect.org.uk Newsletter 107.1 THE COLOUR PAGE! sp. by Chris Pull September 2006 Website: www.stickinsect.org.uk Newsletter 107.2 Editorial Welcome to the September PSG Newsletter; please read and enjoy. I am amazed at the wonderful " 'V^-r«, response I had when seeking contributions for this Newsletter. -

Cop13 Prop. 27

CoP13 Prop. 27 CONSIDERATION OF PROPOSALS FOR AMENDMENT OF APPENDICES I AND II A. Proposal Inclusion of Uroplatus spp. in Appendix II. The most recent update of the species list applicable to the genus Uroplatus (Duméril, 1805) is Raxworthy’s from 2003, published in The natural history of Madagascar by Goodman and Benstead, University of Chicago Press. This update recognized 10 species within the genus Uroplatus, commonly known by its vernacular name of leaf-tailed gecko. These are: U. alluaudi Mocquard, 1894; U. ebenaui Boettger, 1879; U. fimbriatus Schneider, 1797; U. guentheri Mocquard, 1908; U. henkeli Böhme and Ibish, 1990; U. lineatus Duméril and Bibron, 1836; U. malama Nussbaum and Raxworthy, 1995; U. malahelo Nussbaum and Raxworthy, 1994; U. phantasticus Boulenger, 1888 and U. sikorae Boettger, 1913. However, a new species was described in the same year in an issue of Salamandra. This is Uroplatus pietschmanni, identified by Böhle and Schönecker (2003). This species, which closely resembles U. sikorae, was for a long time confused with it and indeed continues to be so. Since this confusion could lead to problems relating not only to population and range limits, but also to how the quantity traded is divided up, and in the absence of proper verification and review on the ground, we take the view that it is preferable to leave it out of consideration for the present. Furthermore, several other forms are under study, and these may constitute new species. Leaf-tailed geckos are among the reptiles which are traded internationally to differing extents, depending on the species concerned. The export data for 2001, 2002 and 2003 supplied by the Ministry of Water and Forests (MEF) make this point very clearly (see the analytical details in the section covering each individual species). -

Invertebrates in Education & Conservation Conference

Invertebrates in Education & Conservation Conference Rio Rico, AZ • July 21 - July 25, 2015 Hosted and Organized by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums’ Terrestrial Invertebrate Taxon Advisory Group (TITAG) NAME: ___________________________________ AUCTION #: ______________________________ 2015 IECC OFFICIAL PROGRAM Sponsors and Exhibitors .......................................................................................... 5 Schedule Overview................................................................................................ 8 Keeping Cool, Collecting and Other Tips............................................................. 10 Tuesday, July 21 TITAG Meeting............................................................................................ 12 Steve Prchal Celebration of Life.............................................................. 12 Wednesday, July 22 Field Trips..................................................................................................... 12 Welcome and Keynote Reception.......................................................... 14 Thursday, July 23 Paper Sessions............................................................................................ 15 Workshops & Field Trips.............................................................................. 19 Friday, July 24 Paper Sessions............................................................................................ 21 Roundtable & Workshops........................................................................ -

New Locality Record of Creobroter Gemmatus (Indian Flower Mantis

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2013): 6.14 | Impact Factor (2013): 4.438 New Locality Record of Creobroter Gemmatus (Indian Flower Mantis / Jeweled Flower Mantis) in the Coastal Region of Contai / Kanthi and its Pattern of Mimicry in Relation to Behaviour Kallol Hajra1, Dr. Sumit Giri2, Prasanta Mandal3 Approved Part-Time Teacher) P. K. College,Contai,West Bengal, India Approved Part-Time Teacher) P. K. College, Contai, West Bengal, India Approved Part-Time Teacher) Ramnagar College, Depal, West Bengal, India Abstract: Indian flower mantis (Creobroter gemmatus) is observed during study period April 2014 to May 2015 from Contai/Kanthi, Purba Medinipur District, W.B. In this article, it is reported that this type of mantis is first time observed in the coastal region of Purba Medinipur district specially to Contai/Kanthi, West Bengal. The wings are green with a yellow eye shaped pattern. The male has a slightly duller coloration on the wings to the female. This type of Mantis also exhibit aggressive type of mimicry and this amazing animal is normally found on top of flowers where they can camouflage themselves and wait for their prey. The host plants of this species are Calotropis procera under family Asclepiadaceae and Pluchea indica under the family Asteraceae . Keyword: Creobroter gemmatus, Coastal region, Contai, mimicry, host plant. 1. Introduction 2. Materials and Method Creobroter gemmatus was first described by Stoll (1813). It Study Site is also called Asian Flower Mantis or Indian flower mantis or Jeweled Flower Mantis in India. The Indian flower mantis Kanthi: It is a small town, situated near the coastal area of is also occurring in Vietnam and South and Southeast Asia. -

Captive Wildlife Exclusion List

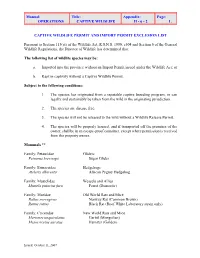

Manual: Title: Appendix: Page: OPERATIONS CAPTIVE WILDLIFE II - 6 - 2 1. CAPTIVE WILDLIFE PERMIT AND IMPORT PERMIT EXCLUSION LIST Pursuant to Section 113(at) of the Wildlife Act, R.S.N.S. 1989, c504 and Section 6 of the General Wildlife Regulations, the Director of Wildlife has determined that: The following list of wildlife species may be: a. Imported into the province without an Import Permit issued under the Wildlife Act; or b. Kept in captivity without a Captive Wildlife Permit. Subject to the following conditions: 1. The species has originated from a reputable captive breeding program, or can legally and sustainably be taken from the wild in the originating jurisdiction. 2. The species are disease free. 3. The species will not be released to the wild without a Wildlife Release Permit. 4. The species will be properly housed, and if transported off the premises of the owner, shall be in an escape-proof container, except where permission is received from the property owner. Mammals ** Family: Petauridae Gliders Petuarus breviceps Sugar Glider Family: Erinaceidae Hedgehogs Atelerix albiventis African Pygmy Hedgehog Family: Mustelidae Weasels and Allies Mustela putorius furo Ferret (Domestic) Family: Muridae Old World Rats and Mice Rattus norvegicus Norway Rat (Common Brown) Rattus rattus Black Rat (Roof White Laboratory strain only) Family: Cricetidae New World Rats and Mice Meriones unquiculatus Gerbil (Mongolian) Mesocricetus auratus Hamster (Golden) Issued: October 11, 2007 Manual: Title: Appendix: Page: OPERATIONS CAPTIVE WILDLIFE II - 6 - 2 2. Family: Caviidae Guinea Pigs and Allies Cavia porcellus Guinea Pig Family: Chinchillidae Chinchillas Chincilla laniger Chinchilla Family: Leporidae Hares and Rabbits Oryctolagus cuniculus European Rabbit (domestic strain only) Birds Family: Psittacidae Parrots Psittaciformes spp.* All parrots, parakeets, lories, lorikeets, cockatoos and macaws. -

Continental Speciation in the Tropics: Contrasting Biogeographic Patterns of Divergence in the Uroplatus Leaf-Tailed Gecko Radiation of Madagascar C

Journal of Zoology Journal of Zoology. Print ISSN 0952-8369 Continental speciation in the tropics: contrasting biogeographic patterns of divergence in the Uroplatus leaf-tailed gecko radiation of Madagascar C. J. Raxworthy1, R. G. Pearson1, B. M. Zimkus1,Ã, S. Reddy1,w, A. J. Deo1,2,z, R. A. Nussbaum3 & C. M. Ingram1 1 American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY, USA 2 Department of Biology, New York University, New York, NY, USA 3 Division of Amphibians and Reptiles, Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA Keywords Abstract speciation; biogeography; systematics; Reptilia; Gekkonidae; Madagascar. A fundamental expectation of vicariance biogeography is for contemporary cladogenesis to produce spatial congruence between speciating sympatric clades. Correspondence The Uroplatus leaf-tailed geckos represent one of most spectacular reptile radia- Christopher J. Raxworthy, American tions endemic to the continental island of Madagascar, and thus serve as an Museum of Natural History, Central Park excellent group for examining patterns of continental speciation within this large West at 79th Street, New York, NY 10024- and comparatively isolated tropical system. Here we present the first phylogeny 5192, USA. Email: [email protected] that includes complete taxonomic sampling for the group, and is based on morphology and molecular (mitochondrial and nuclear DNA) data. This study ÃCurrent address: Department of includes all described species, and we also include data for eight new species. We Herpetology, Museum of Comparative find novel outgroup relationships for Uroplatus and find strongest support for Zoology, Harvard University, 26 Oxford Paroedura as its sister taxon. Uroplatus is estimated to have initially diverged Street, Cambridge, MA 02138, during the mid-Tertiary in Madagascar, and includes two major speciose radia- w USA.