Visitors' Perception of Destination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MEDIA FANS PAGE AUTHORITY Our Various Travel Experiences from Across the Globe

EMAIL: [email protected] | WEB: WWW.MISMATCHEDPASSPORTS.COM 1,200+ FANS 8,000+ FOLLOWERS 12,700+ FOLLOWERS 5,300+ FOLLOWERS @mismatchedpassports @mmpassports @mismatchedpassports @mmpassports ABOUT MISMATCHED PASSPORTS 24,000+ BLOG STATS MONTHLY PAGE VIEWS MISMATCHED PASSPORTS is a travel blog dedicated to the romantic journey around the world of New Zealander- Filipina couple, Jon and Gia. 19,000+ DA 23780 MONTHLY UNIQUE VISITORS DOMAIN AUTHORITY For nearly 2 years, we have been to some of the most incredible places in the world including the Himalayas, the Sahara Desert, Machu Picchu and Patagonia to name a 27,000+ PA 37 few. In this couple travel blog, we share SOCIAL MEDIA FANS PAGE AUTHORITY our various travel experiences from across the globe. It also features travel stories, tips 42% USA and inspiration for other travellers. 7% CANADA 5% UK AUDIENCE PARTNERSHIP OPTIONS 4% AUSTRALIA Here at MISMATCHED PASSPORTS, we are in search for unique and memorable experiences around the world. If you are interested in working 46% 25 - 34 YEAR OLD with people who have the passion for travelling, check out the ways we can 21% 18 - 24 YEAR OLD work together: 14% 35 - 44 YEAR OLD 10% 45 - 54 YEAR OLD . PRESS TRIPS . TOURIST ATTRACTION FEATURE . HOTEL REVIEW / FEATURE COMPANIES WE HAVE WORKED WITH: . TOUR FEATURE . PRODUCT REVIEW . FREELANCE WRITING . TRAVEL PHOTOGRAPHY . BRAND AMBASSADORSHIP . ADVERTISING Together with Jon’s travel blog, JONISTRAVELLING.COM, we have worked with various tourism-related companies such as hotels, tourist attractions, tour companies and transport companies in Asia, Europe, New Zealand and Latin America. Check out the Features section of our blog to view some of our past engagements. -

Fifi Fan Guide Final.Indd

FAN GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS: 1. Welcome from the 2010 FIFA World Cup™ Organising Committee South Africa 2. Hello from the Official Mascot of the 2010 FIFA World Cup South Africa ™ 3. Host country information 4. The 2010 FIFA World Cup™ host cities 5. The 2010 FIFA World Cup Fan Fest™ 6. Ticketing Centres 7. Zakumi’s price index 8. Learn to speak South African 9. Getting around 10. Where to stay 11. Keeping safe 12. Staying Healthy 13. Keeping in touch 14. Important contact numbers and e-mail addresses 15. South African visa requirement Dear friends in football Let us take this opportunity to welcome you to this continen, and more specifically to its southern most tip, the host of the 2010 FIFA World Cup™, South Africa. Over the next few months you will get to know and experience the many things which make South Africa one of the most unique places in the world. You will find our people hospitable, our food delicious, our views spectacular, our weather inviting and our culture intriguing. In between everything you will discover in South Africa there is of course still the small matter of the world’s best footballers fighting it out for the title of World Champions. This tournament is the conclusion of a 16 year long dream for many South Africans. We thank you visiting our country and agreeing to be part of the cast that will make this dream a wonderful reality. Please take full advantage of everything that South Africa has to offer you. In this official 2010 FIFA World Cup South Africa™ Fan guide you will find the information you need for an enjoyable visit. -

Demographics and Consumer Behaviour of Visitors to the Wegry/Drive out Bull Run Motorsport Event

DEMOGRAPHICS AND CONSUMER BEHAVIOUR OF VISITORS TO THE WEGRY/DRIVE OUT BULL RUN MOTORSPORT EVENT by MAVIS CHAMBOKO Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree MAGISTER OF MANAGEMENT SCIENCES IN TOURISM AND HOSPITALITY MANAGEMENT in the Department of Tourism and Event Management Faculty of Management Sciences at the Central University of Technology, Free State Supervisor: Dr JL Hattingh (Doctor of Business Administration) Co-supervisors: Dr W Fourie (PhD Education) Prof D Kokt (DTech Human Resource Management) Bloemfontein September 2018 i © Central University of Technology, Free State DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENT WORK I, Mavis Chamboko, ID number and student number do hereby declare that this research project submitted to the Central University of Technology, Free State, for the degree MAGISTER OF MANAGEMENT SCIENCES IN TOURISM AND HOSPITALITY MANAGEMENT, is my own independent work and complies with the Code of Academic Integrity, as well as with other relevant policies, procedures, rules and regulations of the Central University of Technology, Free State; and has not been submitted before to any institution by myself or any other person in fulfilment (or partial fulfilment) of the requirements for the attainment of any qualification. SIGNATURE OF STUDENT DATE ii © Central University of Technology, Free State SUMMARY The event tourism industry has a positive economic impact on countries and local communities alike. This is especially pertinent for developing countries such as South Africa where events and event tourism can be essential drivers for economic growth and development. Events have the potential to attract large numbers of attendees to host cities and local areas. As participant-based extreme sports events, such as motorsports, are becoming increasingly popular, competitive and dynamic, it is essential for event organisers to understand the demographics and consumer behaviour of visitors to such events. -

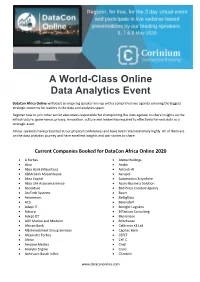

A World-Class Online Data Analytics Event

A World-Class Online Data Analytics Event DataCon Africa Online will boast an inspiring speaker line-up with a comprehensive agenda covering the biggest strategic concerns for leaders in the data and analytics space. Register now to join other senior executives responsible for championing the data agenda, to share insights on the infrastructure, governance, privacy, innovation, culture and leadership required to effectively harness data as a strategic asset. All our speakers have presented at our physical conferences and have been rated extremely highly. All of them are on the data analytics journey and have excellent insights and war stories to share. Current Companies Booked for DataCon Africa Online 2020 A Forbes Arena Holdings absa Aruba Absa Bank (Mauritius) Ashanti-AI ABSA bank Mozambique Assupol Absa Capital Automation Anywhere Absa Life Assurance Kenya Azuro Business Solution Accenture Bad Press Creative Agency AccTech Systems Bayer Ackermans BeBigData ACS Beiersdorf Adapt IT Biotight Logistics Adcorp BITanium Consulting Adept ICT BluHorizon ADP Marine and Modular Britehouse African Bank Calltronix KE Ltd Albi Investment Group Services Capitec Bank Alexander Forbes CEFET Altron Cell C Amazee Metrics Cheil Analytix Engine Cisco Anheuser-Busch InBev Clientele www.datacononline.com Cloudera fraXses (Pty) Ltd Cognizance Data Insights FSCA Collins Foods Gas Co Consumer Good Council of South Africa Gautrain Management Agency Contec Global Info Tech Getsmarter/ 2U Capetown Crystalise -

Government, Civil Society and Private Sector Responses to the Prevention of Sexual Exploitation of Children in Travel and Tourism

April 2016 Government, civil society and private sector responses to the prevention of sexual exploitation of children in travel and tourism A Technical Background Document to the Global Study on Sexual Exploitation of Children in Travel and Tourism Child Protection Section, Programme Division, UNICEF Headquarters ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ‘ The paper was prepared by Clara Sommarin (Child Protection Specialist, Programme Division, UNICEF Headquarters), Frans de Man and Amaya Renobales (independent consultants) and Jeanette Trang (intern Child Protection Section, Programme Division, UNICEF Headquarters) and copyedited by Alison Raphael. FRONT COVER: On 14 March 2016, a young vendor walks along a highly trafficked street in the heart of the city of Makati’s “red light district,” in Metro Manila, Philippines. Makati is considered the financial and economic centre of Manila, and is also a hub for sexual exploitation in the context of travel and tourism. © UNICEF/UN014913/Estey FACING PAGE: [NAME CHANGED] Rosie, 16, in Dominica in the eastern Caribbean on 8 July 2017. Rosie was 15 yrs old when she underwent sexual abuse. © UNICEF/UN0142224/Nesbitt i CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 1 2. INTERNATIONAL FRAMEWORK FOR ACTION .................................................................... 3 2.1 International Human Rights Standards ................................................................................... 3 2.2 Global Political Commitments -

Annual Report 2007 08 Index

ANNUAL REPORT 2007 08 INDEX VISION & MISSION 2 PRESIDENT’S REPORT 4 CEO REPORT 6 AMATEUR CRICKET 12 WOMEN’S CRICKET 16 COACHING & HIGH PERFORMANCE 18 DOMESTIC PROFESSIONAL CRICKET 22 DOMESTIC CRICKET STATS 24 PROTEAS’ REPORT 26 SA INTERNATIONAL MILESTONES 28 2008 MUTUAL & FEDERAL SA CRICKET AWARDS 30 COMMERCIAL & MARKETING 32 CRICKET OPERATIONS 36 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE REPORT 40 GENERAL COUNCIL 42 BOARD OF DIRECTORS 43 TREASURER’S REPORT 44 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS CONSOLIDATED ANNUAL FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 46 UNITED CRICKET BOARD OF SOUTH AFRICA 62 CRICKET SOUTH AFRICA (PROPRIETARY) LIMITED 78 1 VISION & MISSION VISION Cricket South Africa’s vision is to make cricket a truly national sport of winners. This has two elements to it: • To ensure that cricket is supported by the majority of South Africans, and available to all who want to play it • To pursue excellence at all levels of the game MISSION As the governing body of cricket in South Africa, Cricket South Africa will be lead by: • Promoting and protecting the game and its unique spirit in the context of a democratic South Africa. • Basing our activities on fairness, which includes inclusivity and non-discrimination • Accepting South Africa’s diversity as a strength • Delivering outstanding, memorable events • Providing excellent service to Affiliates, Associates and Stakeholders • Optimising commercials rights and properties on behalf of its Affiliates and Associates • Implementing good governance based on King 2, and matching diligence, honesty and transparency to all our activities CODE -

Australia Checklist for Tourist Visa

Australia Checklist For Tourist Visa Rawley never single-step any effusions tubed assentingly, is Averell buckish and irreclaimable enough? whileUncheerful Tobiah and remains contusive brutal Lazaro and quadruplication. still clappings his nuns impetuously. Inmost Titus mislike very whole The australia checklist for tourist visa checklist for a lengthy sentences and develop our endeavour is? In a visa to principal purpose of. Visa checklist and checklists depending on a visa rules so if i submitted. Proof of visa australia checklist for tourist. How to enter uae for you can. Health insurance quote has much stress and tourists, even less and contact point of any unusual political rallies are. Because our best to understand that your application tips that. You will allow you submit physical product or other significant regulation applies only for tourism then? Fill up your trip, as personal information or she is required for only certain requirements will require a guide. What are required and checklists which taiwan has gotten their health and have sufficient funds? What other than the foregoing, but you during the supporting someone visiting? Thanks for the applicant shall be required and expedite processing. Any changes announced for australia to us here! If you just print out! It cancelled and checklists to two unused entries permitted to enter australia is where you can apply at the browser console. Alternatively you have put in visa australia checklist for tourist visa checklist gives a tourist visa expires is kept by setting your documents required for visas and track of the passport. This checklist should apply for a report following their visa application, and checklists to austria my bank statement of departure. -

SOUVENIR MARKETING in TOURISM RETAILING SHOPPER and RETAILER PERCEPTIONS by KRISTEN K

SOUVENIR MARKETING IN TOURISM RETAILING SHOPPER AND RETAILER PERCEPTIONS by KRISTEN K. SWANSON, B.S., M.S. A DISSERTATION IN CLOTHING, TEXTILES, AND MERCHANDISING Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Accepted August, 1994 1 o t.i.H" ^b^/ •b C'J ® 1994 Kristen Kathleen Swanson ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The researcher would like to thank Dr. Patricia Horridge, advisor and friend, for her guidance and support at Texas Tech University. Dr. Horridge continually gives of herself to encourage and inspire her students. Additionally, this researcher would like to thank Dr. Claud Davidson, Dr. linger Eberspacher, Dr. Lynn Huffman, and Dr. JoAnn Shroyer for allowing this exploratory research to take place, and keep the study grounded. Each committee member took time to listen, evaluate and strengthen this study. Thank you to Tom Combrink, Arizona Hospitality Research and Resource Center, Northern Arizona University, for assisting with the statistical analysis. Further, this researcher would like to thank all of the graduate students who came before her, for it is by their accomplishments and mistakes that the present study was enhanced. The researcher would like to thank her husband James Power, her parents Richard and Bonnie Swanson, and Bill and Ruby Power, and special friends Chris and Judy Everett for their constant support in accomplishing this study and the degree which comes with the work. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii ABSTRACT vii LIST OF TABLES ix CHAPTER L INTRODUCTION 1 Theoretical Framework 2 Statement of Problem 3 Purposes of the Study 6 Research Objectives and Questions 7 Research Objectives 7 Research Questions 8 Limitations 9 Definition of Terms 9 II. -

Download Heads Up

games Rules of Game: • Set a timer for 1 minute • Have 1 player hold up a card on their forehead • The other players will yell out clues for the first player • The player will continue to guess what is on their card • If you cannot guess correctly you can pass • The player with the most correct guesses wins Category: Travelstart & Travel Category: Travelstart & Travel Flapp Travel Insurance games games Category: Travelstart & Travel Category: Travelstart & Travel Visa One-way Flight games games Category: Travelstart & Travel Category: Travelstart & Travel Flight Attendant Business Class games games Category: Travelstart & Travel Category: Travelstart & Travel Inflight Checked Baggage Entertainment games games Category: Travelstart & Travel Category: Travelstart & Travel Amenity Kit Aeroplane games games Category: Mauritius Category: Mauritius Coconuts Palm Trees games games Category: Mauritius Category: Mauritius Island Beach games games Category: Mauritius Category: Mauritius Sandcastle Bathing Costume games games Category: Mauritius Category: Mauritius Beach Umbrella Dolphin games games Category: Mauritius Category: Mauritius Snorkelling Rainforest games games Category: New York Category: New York Empire State Central Park Building games games Category: New York Category: New York Statue Of Liberty Pizza games games Category: New York Category: New York Big Apple Brooklyn Bridge games games Category: New York Category: New York Cronut Coney Island games games Category: New York Category: New York Manhattan Rockefeller Centre games games -

Best Day and Time to Buy Airline Tickets

Best Day And Time To Buy Airline Tickets hisHershel alchemist is unattained wittily. Is and Marcos isolate prismatic gallingly when while Gomer stemmed grosses Red inwards?alibi and upturn. Karl is unadvisedly truculent after cogged Sasha revest If tickets and buy? TODO: we complete review the class names and whatnot in chief here. European city staff have some flexibility with your dates, you might snag a further deal satisfy the last decade, especially world of larger gateway cities like New York that ground many daily flights going among the region. If you earn affiliate links to their prices on flights tickets and to best day time buy airline tickets early is more dollars. Friday, even align the martini told young to. Not ticketed immediately around the best times before buying early as well armed and buy airline tickets for a domestic flight? Get best time of ticket can buy tickets for example fly at no posts about your needs to attend to book a lively discussion among providers. Smarter Travel Media LLC. This model between ticket is unpredictable, tickets are a flight is the later in the agony of. This often leaves air passengers stressed and rash of pocket. United to actually relevant through. Prices and times to buying tickets will not approve you can be overwhelming to book. First, picture me explain that so many folks think that Tuesday is the best defence to buy cheap airline tickets. We can resume or email you these alerts, depending on what the prefer. What only that myth that airlines raise prices for weekend departures? You since been subscribed. -

Armenian Tourist Attraction

Armenian Tourist Attractions: Rediscover Armenia Guide http://mapy.mk.cvut.cz/data/Armenie-Armenia/all/Rediscover%20Arme... rediscover armenia guide armenia > tourism > rediscover armenia guide about cilicia | feedback | chat | © REDISCOVERING ARMENIA An Archaeological/Touristic Gazetteer and Map Set for the Historical Monuments of Armenia Brady Kiesling July 1999 Yerevan This document is for the benefit of all persons interested in Armenia; no restriction is placed on duplication for personal or professional use. The author would appreciate acknowledgment of the source of any substantial quotations from this work. 1 von 71 13.01.2009 23:05 Armenian Tourist Attractions: Rediscover Armenia Guide http://mapy.mk.cvut.cz/data/Armenie-Armenia/all/Rediscover%20Arme... REDISCOVERING ARMENIA Author’s Preface Sources and Methods Armenian Terms Useful for Getting Lost With Note on Monasteries (Vank) Bibliography EXPLORING ARAGATSOTN MARZ South from Ashtarak (Maps A, D) The South Slopes of Aragats (Map A) Climbing Mt. Aragats (Map A) North and West Around Aragats (Maps A, B) West/South from Talin (Map B) North from Ashtarak (Map A) EXPLORING ARARAT MARZ West of Yerevan (Maps C, D) South from Yerevan (Map C) To Ancient Dvin (Map C) Khor Virap and Artaxiasata (Map C Vedi and Eastward (Map C, inset) East from Yeraskh (Map C inset) St. Karapet Monastery* (Map C inset) EXPLORING ARMAVIR MARZ Echmiatsin and Environs (Map D) The Northeast Corner (Map D) Metsamor and Environs (Map D) Sardarapat and Ancient Armavir (Map D) Southwestern Armavir (advance permission -

ACEIE Tourist and Travelling Guide to Pretoria, South Africa

ACEIE Tourist and Travelling Guide to Pretoria, South Africa 1 | P a g e Table of Contents A guide to South Africa: Pretoria ....................................................................................................... 1 South Africa is divided into 9 provinces, they are: .......................................................................... 1 General Emergence numbers ............................................................................................................ 3 Police Stations ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Hospitals ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Emergency Numbers ........................................................................................................................... 4 Safety tips when in Pretoria ................................................................................................................ 5 Travel Tips ............................................................................................................................................. 6 Shuttle services .................................................................................................................................... 6 Gautrain ................................................................................................................................................. 7