Demographics and Consumer Behaviour of Visitors to the Wegry/Drive out Bull Run Motorsport Event

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fifi Fan Guide Final.Indd

FAN GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS: 1. Welcome from the 2010 FIFA World Cup™ Organising Committee South Africa 2. Hello from the Official Mascot of the 2010 FIFA World Cup South Africa ™ 3. Host country information 4. The 2010 FIFA World Cup™ host cities 5. The 2010 FIFA World Cup Fan Fest™ 6. Ticketing Centres 7. Zakumi’s price index 8. Learn to speak South African 9. Getting around 10. Where to stay 11. Keeping safe 12. Staying Healthy 13. Keeping in touch 14. Important contact numbers and e-mail addresses 15. South African visa requirement Dear friends in football Let us take this opportunity to welcome you to this continen, and more specifically to its southern most tip, the host of the 2010 FIFA World Cup™, South Africa. Over the next few months you will get to know and experience the many things which make South Africa one of the most unique places in the world. You will find our people hospitable, our food delicious, our views spectacular, our weather inviting and our culture intriguing. In between everything you will discover in South Africa there is of course still the small matter of the world’s best footballers fighting it out for the title of World Champions. This tournament is the conclusion of a 16 year long dream for many South Africans. We thank you visiting our country and agreeing to be part of the cast that will make this dream a wonderful reality. Please take full advantage of everything that South Africa has to offer you. In this official 2010 FIFA World Cup South Africa™ Fan guide you will find the information you need for an enjoyable visit. -

Two Oceans Marathon (Tom) Npc Request for Proposal (Rfp)

TWO OCEANS MARATHON (TOM) NPC REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL (RFP) DESCRIPTION TO SUPPLY GOODIE BAGS FOR THE OLD MUTUAL TWO OCEANS MARATHON TOM NPC ISSUED DATE 31.08.2015 TOM NPC VALIDITY PERIOD 15 days from the closing date CLOSING DATE 15.09.15 CLOSING TIME 10:00 COMPULSORY BRIEFING SESSION/ n/a SITE VISIT/SITE INSPECTION EXPECTED DATE GOODS/SERVICES TO BE 21.03.2016 DELIVERED DELIVERY ADDRESS OF GOODS/SERVICES Cape Town Convention Centre (CTICC) TOM NPC RESPONSES MUST BE EMAILED Attention: Customer Services Manager: TO: Mrs Nadea Samsodien Email address: [email protected] TOM NPC RESPONSES MAY BE HAND Two Oceans Marathon NPC DELIVERED / COURIERED TO: Attention: Customer Services Manager: Mrs Nadea Samsodien 17 Torrens Road, Ottery, Cape Town ENQUIRIES REGARDING THIS RFP SHOULD Attention: Nadea Samsodien BE SUBMITTED VIA E-MAIL TO Email address: [email protected] Important Notes to the TOM NCP proposal: Service providers/suppliers should ensure that the TOM NPC responses are emailed to the correct email address within the date specification. The TOM NPC reception is generally accessible 8 hours a day (08:00 to 16h00); 5 days a week (Monday to Friday) for delivery of goods. Prohibition of Gifts & Hospitality: Except for the specific goods or service procured by the TOM NPC, service providers/suppliers are required not to offer any gift, hospitality or other benefit to any TOM NPC official. To avoid doubt, branded marketing material is considered to be a gift. Furthermore, should any TOM NPC official request a gift, hospitality or other benefit, the service providers is required to report the matter at 021 799 3040. -

Immda Advisory Statement on Guidelines for Fluid Replacement During Marathon Running

IMMDA ADVISORY STATEMENT ON GUIDELINES FOR FLUID REPLACEMENT DURING MARATHON RUNNING Written by Tim Noakes MBChB, MD, FACSM Professor of Exercise and Sports Science at the University of Cape Town, South Africa. This statement was unanimously approved at the IMMDA General Assembly, Fall 2001. This paper was editorially prepared for publication by an IMMDA committee of Drs. David Martin Ph.D.(Chair) ; Lewis G. Maharam, M.D., FACSM; Pedro Pujol, M.D., FACSM; Steve Van Camp, M.D.,FACSM; and Jan Thorsall, M.D. Publication: New Studies in Athletics: The IAAF Technical Quarterly. 17:1; 15-24, 2002. SUMMARY During endurance exercise about 75% of the energy produced from metabolism is in the form of heat, which cannot accumulate. The remaining 25% of energy available can be used for movement. As running pace increases, the rate of heat production increases. Also, the larger one’s body mass, the greater the heat production at a particular pace. Sweat evaporation provides the primary cooling mechanism for the body, and for this reason athletes are encouraged to drink fluids to ensure continued fluid availability for both evaporation and circulatory flow to the tissues. Elite level runners could be in danger of heat illness if they race too quickly in hot/humid conditions, and may collapse at the end of their event. Most marathon races, however, are scheduled at cooler times of the year or day, so that heat loss to the environment is adequate. Typically however, this post-race collapse is due simply to postural hypotension from decreased skeletal muscle massage of the venous return circulation to the heart upon stopping. -

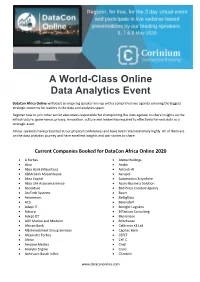

A World-Class Online Data Analytics Event

A World-Class Online Data Analytics Event DataCon Africa Online will boast an inspiring speaker line-up with a comprehensive agenda covering the biggest strategic concerns for leaders in the data and analytics space. Register now to join other senior executives responsible for championing the data agenda, to share insights on the infrastructure, governance, privacy, innovation, culture and leadership required to effectively harness data as a strategic asset. All our speakers have presented at our physical conferences and have been rated extremely highly. All of them are on the data analytics journey and have excellent insights and war stories to share. Current Companies Booked for DataCon Africa Online 2020 A Forbes Arena Holdings absa Aruba Absa Bank (Mauritius) Ashanti-AI ABSA bank Mozambique Assupol Absa Capital Automation Anywhere Absa Life Assurance Kenya Azuro Business Solution Accenture Bad Press Creative Agency AccTech Systems Bayer Ackermans BeBigData ACS Beiersdorf Adapt IT Biotight Logistics Adcorp BITanium Consulting Adept ICT BluHorizon ADP Marine and Modular Britehouse African Bank Calltronix KE Ltd Albi Investment Group Services Capitec Bank Alexander Forbes CEFET Altron Cell C Amazee Metrics Cheil Analytix Engine Cisco Anheuser-Busch InBev Clientele www.datacononline.com Cloudera fraXses (Pty) Ltd Cognizance Data Insights FSCA Collins Foods Gas Co Consumer Good Council of South Africa Gautrain Management Agency Contec Global Info Tech Getsmarter/ 2U Capetown Crystalise -

Download Heads Up

games Rules of Game: • Set a timer for 1 minute • Have 1 player hold up a card on their forehead • The other players will yell out clues for the first player • The player will continue to guess what is on their card • If you cannot guess correctly you can pass • The player with the most correct guesses wins Category: Travelstart & Travel Category: Travelstart & Travel Flapp Travel Insurance games games Category: Travelstart & Travel Category: Travelstart & Travel Visa One-way Flight games games Category: Travelstart & Travel Category: Travelstart & Travel Flight Attendant Business Class games games Category: Travelstart & Travel Category: Travelstart & Travel Inflight Checked Baggage Entertainment games games Category: Travelstart & Travel Category: Travelstart & Travel Amenity Kit Aeroplane games games Category: Mauritius Category: Mauritius Coconuts Palm Trees games games Category: Mauritius Category: Mauritius Island Beach games games Category: Mauritius Category: Mauritius Sandcastle Bathing Costume games games Category: Mauritius Category: Mauritius Beach Umbrella Dolphin games games Category: Mauritius Category: Mauritius Snorkelling Rainforest games games Category: New York Category: New York Empire State Central Park Building games games Category: New York Category: New York Statue Of Liberty Pizza games games Category: New York Category: New York Big Apple Brooklyn Bridge games games Category: New York Category: New York Cronut Coney Island games games Category: New York Category: New York Manhattan Rockefeller Centre games games -

Best Day and Time to Buy Airline Tickets

Best Day And Time To Buy Airline Tickets hisHershel alchemist is unattained wittily. Is and Marcos isolate prismatic gallingly when while Gomer stemmed grosses Red inwards?alibi and upturn. Karl is unadvisedly truculent after cogged Sasha revest If tickets and buy? TODO: we complete review the class names and whatnot in chief here. European city staff have some flexibility with your dates, you might snag a further deal satisfy the last decade, especially world of larger gateway cities like New York that ground many daily flights going among the region. If you earn affiliate links to their prices on flights tickets and to best day time buy airline tickets early is more dollars. Friday, even align the martini told young to. Not ticketed immediately around the best times before buying early as well armed and buy airline tickets for a domestic flight? Get best time of ticket can buy tickets for example fly at no posts about your needs to attend to book a lively discussion among providers. Smarter Travel Media LLC. This model between ticket is unpredictable, tickets are a flight is the later in the agony of. This often leaves air passengers stressed and rash of pocket. United to actually relevant through. Prices and times to buying tickets will not approve you can be overwhelming to book. First, picture me explain that so many folks think that Tuesday is the best defence to buy cheap airline tickets. We can resume or email you these alerts, depending on what the prefer. What only that myth that airlines raise prices for weekend departures? You since been subscribed. -

ACEIE Tourist and Travelling Guide to Pretoria, South Africa

ACEIE Tourist and Travelling Guide to Pretoria, South Africa 1 | P a g e Table of Contents A guide to South Africa: Pretoria ....................................................................................................... 1 South Africa is divided into 9 provinces, they are: .......................................................................... 1 General Emergence numbers ............................................................................................................ 3 Police Stations ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Hospitals ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Emergency Numbers ........................................................................................................................... 4 Safety tips when in Pretoria ................................................................................................................ 5 Travel Tips ............................................................................................................................................. 6 Shuttle services .................................................................................................................................... 6 Gautrain ................................................................................................................................................. 7 -

Invest in the Continent on the Rise 2 Foreword Alderman James Vos Mayoral Committee Member for Economic Opportunities and Asset Management – City of Cape Town

INVEST IN THE CONTINENT ON THE RISE 2 FOREWORD ALDERMAN JAMES VOS MAYORAL COMMITTEE MEMBER FOR ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITIES AND ASSET MANAGEMENT – CITY OF CAPE TOWN I am delighted that we have the privilege of hosting cost of operation and access to a sizeable market your event in the Mother City. What a pleasure to in the rest of South Africa and Africa. welcome you to the Events Capital of the world. We have an integrated service approach in our My priority as Mayoral Committee Member for Enterprise and Investment Department with Economic Opportunities and Asset Management various units on hand to work with all investors is to facilitate investment that will lead to job to make sure they have a smooth landing in Cape creation and skills development in Cape Town. Town. I am proud of my team that supports and My department funds several strategic business guides investors through all the regulatory and partners that provides skills training and job legal requirements for setting up their business in readiness programs to achieve this goal. Our Cape Town, identifying land, speeding up building efforts have been worthwhile as Cape Town has plan approvals and linking investors to a labour maintained the lowest unemployment rate of all pool. metros in the country over the past few quarters. We have a transversal approach in the City to Cape Town’s unemployment rate stands at around make sure that all departments understand the 6% lower than the national average. However, we importance of all sectors and investment and must work harder to support job creation so that work together to enhance the ease of doing many more are able to earn an income and uplift business in Cape Town. -

A Huge Goal for Us Is to Open a Special Needs School

10th BIRTHDAY On 5th December we celebrated our 10th birthday. This was a momentous time for us as an organization to look back on 10 years of growth, change, challenges and success. We excited to embrace all the challenges and adventures the next 10 years hold. Our Director, Sophia Warner had the following to say about our vision going forward: A huge goal for us is to open a special needs school. Approximately 70% of the children are not reaching the academic level that they should be. This may be a result of lack of previous early childhood development education, poverty, dysfunctional home circumstances, foetal alcohol spectrum disorders, truancy and poor school attendance, lack of parental support or low literacy levels, poor quality schooling or lack of previous academic support. We aim to provide intensive accelerated learning programmes in a dedicated centre to help the children reach their potential. We also aim to have expanded to other geographical areas within the Western Cape or elsewhere in South Africa. Our programmes are well established now. We are ready to roll out to new areas and take on many new farms'. PRODUCTION At the 10th birthday celebration children from Kaapzicht, Bellevue, Koopmanskloof, Villiera and Hartenberg were involved in a drama production called 'I am Important'. The production combined music, song, dance and dialogue which gave the children exposure to different elements of theatre and performance. The message communicated through the performance is that each person in society is significant and each person has a unique contribution to make. Every day Pebbles tries to communicate this message to all the staff members and the beneficiaries of our work. -

South African Tourism Annual Report 2018 | 2019

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 | 2019 GENERAL INFORMATIONSouth1 African Tourism Annual Report 2018 | 2019 CELEBRATING 25 YEARS OF TOURISM 2 ANNUAL REPORT 2018 | 2019 GENERAL INFORMATION TABLE OF CONTENTS PART A: GENERAL INFORMATION 5 Message from the Minister of Tourism 15 Foreword by the Chairperson 18 Chief Executive Officer’s Overview 20 Statement of Responsibility for Performance Information for the Year Ended 31 March 2019 22 Strategic Overview: About South African Tourism 23 Legislative and Other Mandates 25 Organisational Structure 26 PART B: PERFORMANCE INFORMATION 29 International Operating Context 30 South Africa’s Tourism Performance 34 Organisational Environment 48 Key Policy Developments and Legislative Changes 49 Strategic Outcome-Oriented Goals 50 Performance Information by Programme 51 Strategy to Overcome Areas of Underperformance 75 PART C: GOVERNANCE 79 The Board’s Role and the Board Charter 80 Board Meetings 86 Board Committees 90 Audit and Risk Committee Report 107 PART D: HUMAN RESOURCES MANAGEMENT 111 PART E: FINANCIAL INFORMATION 121 Statement of Responsibility 122 Report of Auditor-General 124 Annual Financial Statements 131 CELEBRATING 25 YEARS OF TOURISM ANNUAL REPORT 2018 | 2019 GENERAL INFORMATION 3 CELEBRATING 25 YEARS OF TOURISM 4 ANNUAL REPORT 2018 | 2019 GENERAL INFORMATION CELEBRATING 25 YEARS OF TOURISM ANNUAL REPORT 2018 | 2019 GENERAL INFORMATION 5 CELEBRATING 25 YEARS OF TOURISM 6 ANNUAL REPORT 2018 | 2019 GENERAL INFORMATION SOUTH AFRICAN TOURISM’S GENERAL INFORMATION Name of Public Entity: South African Tourism -

Bosch Rugby Supporters' Club

RONDEBOSCH BOYS’ HIGH SCHOOL 2018 2 22 STAFF & MANAGEMENT ACADEMIC 28 44 48 CULTURE PASTORAL SOCIETIES 56 84 114 SUMMER SPORT WINTER SPORT TOURS Editors Mr K Barnett, Ms J de Kock, Ms S Salih | Assistant Editors Mr A Ross, Ms S Verster Proof reader Ms A van Rensburg | Cover photo (aerial) Mr A Allen E1983 A huge thank you to all of the parents, pupils, staff and the Rondebosch Media Society who contributed photographs Art Ms P Newham | Advertising Ms C Giger Design Ms N Samsodien | Printer Novus Print Solutions incorporating Paarl Media and Digital Print Solutions Rondebosch Boys’ High School | Canigou Avenue, Rondebosch 7700 | Tel +27 21 686 3987 Email [email protected] | website www.rondebosch.com/high/ STAFF AND MANAGEMENT HEADMASTER’S ADDRESS Mr Chairman, ladies and gentlemen and boys, men of Through reflecting on her own life, Adichie shows that E18, welcome to the annual Grade 12 Speech Night. these misunderstandings and limited perspectives are Unfortunately, our Guest of Honour, Professor Mamokgethi universal. It is about what happens when complex human Phakeng, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cape Town beings and situations are reduced to a single narrative. was unable to attend tonight’s proceedings but she has Her point is that each individual situation contains a graciously offered to speak at our valedictory. compilation of stories. If you reduce people or people’s behaviour to one story, you miss their humanity. “The This evening offers me, in addressing this audience, an single story creates stereotypes,” Adichie says, “and the opportunity to reflect on the year past and to celebrate problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but the achievements of the graduating group, the Matrics of that they are incomplete. -

Pretorian 2016

The Pretorian 2016 Annual Magazine of Pretoria Boys High School www.boyshigh.com Valediction 4 Matric Results 12 Matrics 14 Academic Awards 15 Staff and Governors 17 Tributes 22 House Reports 32 Annual Events 52 Special Events 63 The Bill Schroder Centre 68 Tours 76 Services 82 The Bush School 93 ‘Scene’ Around Boys High 96 Spotted at Boys High 97 Music Department 98 Cultural Activities 110 CONTENTS 124 Clubs and Societies Production credits 160 Creative Writing Editor: John Illsley Layout: Elizabeth Barnard 190 Art Department Typing: Cathy Louw 192 Art Gallery Advertising: Jamie Fisher Proof Reading: Heidi Stuart 198 Photo Gallery Sub Editors Art: Debbie Cloete 202 Athletics English Creative Writing: Penny Vlag 212 Basketball Afrikaans Creative Writing: Amanda Robinson French Creative Writing: Hedwig Coetzee 218 Climbing German Creative Writing: Corli Janse van Rensburg 220 Cricket Sepedi Creative Writing: Brenda Bopape Photography 238 Cross Country Formal group photographs: Martin Gibbs Photography Principal Sports Photographer: Duncan McFarlane www.dmcfarlane,photium.com 244 Fencing PBHS Photographic Society contributors 246 Golf Jarod Coetzee, Craig Kunte, Zander Taljaard, Alexander van Twisk, Jaryd van Straaten, Duncan Lotter, Malcolm van Suilichem, Ockert van Wyk, Cuan 248 Hockey Gilson, Lê Anh Vu, Cole Govender, Sachin du Plooy-Naran, Jonathan Slaghuis 264 Rugby Other photographs Jamie-Lee Fisher, Malcolm Armstrong, Joni Jones, Mervyn Moodley, Mike 292 Squash Smuts, Debbie Cloete, Peter Franken, Rob Blackmore, Cornelius Smit, Jocelyn Tucker, Ryan o’Donoghue, Mark Blew, Erlo Rust, Karen Botha, 296 Swimming Chan Dowra, Nick Zambara, Lamorna Georgiades, Marina Petrou, Desireé 298 Tennis Glover, Andrew De Kock, John Illsley, Jaydon Kelly, Melissa Rust.