Bahawalpur City Thesis Submitted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

33422717.Pdf

1 Contents 1. PREFACE ........................................................................................................................................... 4 2. OVERVIEW OF THE CULTURAL ASSETS OF THE COMMUNITIES OF DISTRICTS MULTAN AND BAHAWALPUR ................................................................... 9 3. THE CAPITAL CITY OF BAHAWALPUR AND ITS ARCHITECTURE ............................ 45 4. THE DECORATIVE BUILDING ARTS ....................................................................................... 95 5. THE ODES OF CHOLISTAN DESERT ....................................................................................... 145 6. THE VIBRANT HERITAGE OF THE TRADITIONAL TEXTILE CRAFTS ..................... 165 7. NARRATIVES ................................................................................................................................... 193 8. AnnEX .............................................................................................................................................. 206 9. GlossARY OF TERMS ................................................................................................................ 226 10. BIBLIOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................................. 234 11. REPORTS .......................................................................................................................................... 237 12 CONTRibutoRS ............................................................................................................................ -

Abbreviations and Acronyms

PART II] THE GAZETTE OF PAKISTAN, EXTRA., JULY 23, 2019 1505(1) ISLAMABAD, TUESDAY, JULY 23, 2019 PART II Statutory Notifications (S. R. O.) GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN REVENUE DIVISION (Federal Board of Revenue) NOTIFICATIONS Islamabad, the 23rd July, 2019 (INCOME TAX) S.R.O. 829(I)/2019.—In exercise of the powers conferred by sub- section (4) of section 68 of the Income Tax Ordinance, 2001 (XLIX of 2001) and in supersession of its Notification No. S.R.O. 111(I)/2019 dated the lst February, 2019, the Federal Board of Revenue is pleased to notify the value of immoveable properties in columns (3) and (4) of the Table below in respect of areas of Abbottabad classified in column (2) thereof. (2) This notification shall come into force with effect from 24th July, 2019. 1505 (1—211) Price: Rs. 320.00 [1143(2019)/Ex.Gaz.] 1505(2) THE GAZETTE OF PAKISTAN, EXTRA., JULY 23, 2019 [PART II ABBOTTABAD Value of Commercial Value of Residential S.No. Areas property per marla property per marla (in Rs.) (in Rs.) (1) (2) (3) (4) 1 Main Bazar, Sadar Bazar, Jinnah Road, Masjid Bazar, 2,580,600 910,800 Sarafa Bazar Gardawara Gali Kutchery Road, Shop and Market. 2 Abbottabad Bazar 2,580,600 759,000 3 Iqbal Road 1,214,400 531,300 4 Mansehra Road 1,973,400 531,300 5 Jinnah Abad 2,277,000 1,062,600 6 Habibullah Colony - 1,062,600 7 Kaghan Colony 759,000 455,400 S.R.O. 830(I)/2019.—In exercise of the powers conferred by sub-section (4) of section 68 of the Income Tax Ordinance, 2001 (XLIX of 2001) and in supersession of its Notification No. -

Role of Libraries & Information Centers in Promoting Culture and Architecture in Cholistan Desert, South Punjab Pakistan

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln October 2013 Role of Libraries & Information Centers in Promoting Culture and Architecture in Cholistan Desert, South Punjab Pakistan Rubina Bhatti Islamia University of Bahawalpur, [email protected] Mazhar Hayat Librarian, Govt. Post Graduate College for Women, TEVTA, Bahawalpur, [email protected] Sarwat Mukhtar Lecturer: Deptt. Library & Information Science, The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Bhatti, Rubina; Hayat, Mazhar; and Mukhtar, Sarwat, "Role of Libraries & Information Centers in Promoting Culture and Architecture in Cholistan Desert, South Punjab Pakistan" (2013). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 1002. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1002 Role of Libraries & Information Centers in Promoting Culture and Architecture in Cholistan Desert, South Punjab Pakistan Mazhar Hayat Dr. Rubina Bhatti Sarwat Mukhtar Abstract This study was conducted with purpose to explore the elapsed and hidden treasures of Cholistan dessert in South Punjab, Pakistan. It discusses the role of university libraries of South Punjab, museums, Pakistan National library, Pakistan Library Association and HEC, digitization centers and documentation centers. It suggests that grant must be provided for research activities in different aspects of Cholistani Culture including Tribal Folks, Art, Culture, loriyan and old songs. HEC and Punjab government should provide special funds to libraries to support endangered art and culture like Chunri, khusa, paintings, weaving, the famous puppet show of Cholistan, folk songs of Darawar and cultural theatre. -

Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) Final Report August 2018

PUNJAB SANITATION AND NUTRITION IMPROVEMENT PROJECT (PSNIP) Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) Final Report August 2018 Housing, Urban Development and Public Health Engineering Department PUNJAB SANITATION AND NUTRITION IMPROVEMENT PROJECT (PSNIP) Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) Final Report August 2018 Housing, Urban Development and Public Health Engineering Department Environmental and Social Management Framework(ESMF) Executive Summary EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Punjab Housing and Urban Development-Public Health Engineering Department (HUD PHED) and Government of Punjab (GoP) with the financial assistance of World Bank (WB) and technical support of UNICEF in Pakistan are planning to undertake Punjab Sanitation and Nutrition Improvement Project (PSNIP)reflected in Annual Development Program 2017-18 under Water Supply and Sanitation Sector .PSNIP is the part of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) Program under stunting reduction program in 11 Districts of Multan, Bahawalpur and D.G. Khan Divisions. PHED hired an individual ESMF Consultant to fulfill World Bank Operational Policies and local environmental/social laws and to prepare Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) for PSNIP at its inception stage via assessing the project’s environmental and social viability through various environmental components like air, water, noise, land, ecology along with the parameters of human interest and mitigating adverse impacts along with chalking out of guidelines, SOPs, procedure for detailed EA before -

1.2. Environmental and Social Management Framework (Esmf)

Environmental and Social Management Framework(ESMF) PUNJAB HUMAN CAPITAL INVESTMENT PROJECT (PHCIP) Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMNETAL & SOCIAL MANAGEMNET FRAMEWORK (ESMF) Public Disclosure Authorized Final Draft Report October 2019 Proposed to be implemented Public Disclosure Authorized By Punjab Social Protection Authority, Primary & Secondary Health Department through Punjab Health Facilities Management Company (PHFMC), &School Education Department (SED) Public Disclosure Authorized EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Government of Punjab Province intends to implement Punjab Human Capital Investment Project (HCIP) with the proposed assistance of the World Bank (WB). Given the multi-sectoral operations, the project is proposed to be implemented jointly through multiple entities with Punjab Social Protection Authority (PSPA) as the lead agency and other entities including: School Education Department (SED) and Primary and Secondary Health Department (PSHD) through Punjab Health Facilities Management Company (PHFMC). Other entities in Punjab such as the Integrated Reproductive Maternal & Newborn Child Health & Nutrition Program (IRMNCH & NP) and Population Welfare Department Punjab (PWD) will provide support. The Government of Punjab in line with the prevailing legislation in the Country, and WB safeguard policies, has carried out an environmental and social assessment of the Project and accordingly the present Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) has been prepared. PROJECT OVERVIEW1 Project Develoment Objective (PDO) The proposed project development objective (PDO) is to increase the utilization of quality health services, and economic and social inclusion programs, among poor and vulnerable households in select districts in Punjab. Project Components The Project has following three components with brief description provided below2: Component 1 : Health services quality and utilization: The ultimate goal of this component’s activities is to improve children’s health, especially those coming from poor and vulnerable households. -

Bahawalpur Specified in Columns (2), (3) and (4) Thereof

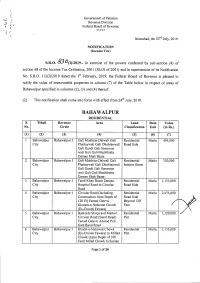

H Government of Pakistan S"li s- Revenue Division 9 Federal Board of Revenue It ' t 'kick'k-k f ii ■> Islamabad, the 23rd July, 2019. NOTIFICATION (Income Tax) S.R.O. ^(I)/2019.- In exercise of the powers conferred by sub-section (4) of section 68 of the Income Tax Ordinance, 2001 (XLIX of 2001) and in supersession of its Notification No. S.R.O. 112(I)/2019 dated the 1st February, 2019, the Federal Board of Revenue is pleased to notify the value of immoveable properties in column (7) of the Table below in respect of areas of Bahawalpur specified in columns (2), (3) and (4) thereof. (2) This notification shall come into force with effect from 24th July, 2019. BAHAWALPUR RESIDENTIAL S. Tehsil Revenue Area Land Rate Value No. Circle Classification Unit (in Rs.) (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) 1 Bahawalpur Bahawalpur I Gali Mukhian Dalwali Gali Residential Marla 495,000 City Phattaywali Gali Dhobianwali Road Side Gali Gandi Gali Sonaroon wali Gali Gali Machihatta Daman Shah Bazar 2 Bahawalpur Bahawalpur 1 Gali Mukhian Dalwali Gali Residential Marla 330,000 City Phattaywali Gali Dhobianwali Interior Street Gali Gandi Gali Sonaroon wali Gali Gali Machihatta Daman Shah Bazar Bahawalpur Bahawalpur I Fateh Khan Bazar Zanana Residential Marla 1,155,000 City Hospital Road to Circular Road Side Road 4 Bahawalpur Bahawalpur I Circular Road (Including Residential Marla 2,475,000 City Construction Upto Depth of Road Side 120 Ft) Farced Gate to Beyond 120' Khatam-e-Nabowat Chowk Feet (Ex-Chowk Fawara) 5 Bahawalpur Bahawalpur I Backside Shops and Market Residential -

Final List of Electoral Rolls of Registered Graduates As Members University Senate Under Section 22(1)(Xvi) of the Islamia University of Bahawalpur Act 1975 Uni

The Islamia University of Bahawalpur Final list of Electoral Rolls of Registered Graduates as members University Senate under section 22(1)(xvi) of the Islamia University of Bahawalpur Act 1975 Uni. Which Sr. # Name Father's Name Exam. Passed Registration No. Address Graduated H. # B-III/619 Govt. Girls High School, Street, Mohallah Qazina, 1 Abdul Haq Yar Muhammad B.Sc PU LHR Rahimyar Khan 2 Abdul hadi Khwaja M. M. Ramzan B.A PU LHR 36/10 Riaz Colony Bahawalpur 3 Abdus Samad Ahmad Abdul Wahid B.A IUB Al-Hafeez Manzil Mohallah Bagh Mahi Bahawalpur 4 Abdul hadi Khwaja Allah Bakhsh B.A PU LHR Principal Govt. Inter College Yazman 5 Azra Naseem Akhtar Abdul Rehman B.A IUB H. # 393/C Satellite Town Bahawalpur Qureshi Street, Opposite Dubai Mahal College, St. No.6, H.No.B-X- 6 Ejaz Ahmad Qureshi Hafiz Faiz Ahmad B.A IUB 128/4, Saddiq Colony, Bahawalpur 7 Abdul Majeed Kausar Qadir Bakhsh Bhatti B.A IUB Bahawalpur Arts Council Bahawalpur 8 Abdul Karim Arshad R. Rahim Bakhsh B.A PU LHR zulfiqar St. Colony Haji Mohad Khan, RYK 9 Abdul Qayyum Shahid Abdul Latif B.A IUB 775/C Satellite Town Bahawalpur 10 Abida Kalsoom Qazi Baqa Mohammad B.A IUB Mohalah Qazian Rahimyar Khan 11 Abdul Rauf Abdul Latif B.A IUB 775/C Sattelite Town Bahawalpur 12 Arif Tanveer Ch. Ghulam Ali B.A PU LHR 37-B, Model Town, B, Bahawalpur 13 Amtul Rehman Abdul Aziz B.A IUB C/O Head Master Govt. Tameer -e- Millat H/S Sadiq Abad 14 Miss Alia Batool Abdul Qadir B.A IUB Mashood Iqbal Advocate Mohallah Chah Fatha Khan Bahawalpur 15 Abid Hussain Shah S.