PHYLOGENY of LAMPRIDIFORM FISHES John E. Olney, G. David

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BONY FISHES 602 Bony Fishes

click for previous page BONY FISHES 602 Bony Fishes GENERAL REMARKS by K.E. Carpenter, Old Dominion University, Virginia, USA ony fishes constitute the bulk, by far, of both the diversity and total landings of marine organisms encoun- Btered in fisheries of the Western Central Atlantic.They are found in all macrofaunal marine and estuarine habitats and exhibit a lavish array of adaptations to these environments. This extreme diversity of form and taxa presents an exceptional challenge for identification. There are 30 orders and 269 families of bony fishes presented in this guide, representing all families known from the area. Each order and family presents a unique suite of taxonomic problems and relevant characters. The purpose of this preliminary section on technical terms and guide to orders and families is to serve as an introduction and initial identification guide to this taxonomic diversity. It should also serve as a general reference for those features most commonly used in identification of bony fishes throughout the remaining volumes. However, I cannot begin to introduce the many facets of fish biology relevant to understanding the diversity of fishes in a few pages. For this, the reader is directed to one of the several general texts on fish biology such as the ones by Bond (1996), Moyle and Cech (1996), and Helfman et al.(1997) listed below. A general introduction to the fisheries of bony fishes in this region is given in the introduction to these volumes. Taxonomic details relevant to a specific family are explained under each of the appropriate family sections. The classification of bony fishes continues to transform as our knowledge of their evolutionary relationships improves. -

Phylogeny Classification Additional Readings Clupeomorpha and Ostariophysi

Teleostei - AccessScience from McGraw-Hill Education http://www.accessscience.com/content/teleostei/680400 (http://www.accessscience.com/) Article by: Boschung, Herbert Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Gardiner, Brian Linnean Society of London, Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, United Kingdom. Publication year: 2014 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1036/1097-8542.680400 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1036/1097-8542.680400) Content Morphology Euteleostei Bibliography Phylogeny Classification Additional Readings Clupeomorpha and Ostariophysi The most recent group of actinopterygians (rayfin fishes), first appearing in the Upper Triassic (Fig. 1). About 26,840 species are contained within the Teleostei, accounting for more than half of all living vertebrates and over 96% of all living fishes. Teleosts comprise 517 families, of which 69 are extinct, leaving 448 extant families; of these, about 43% have no fossil record. See also: Actinopterygii (/content/actinopterygii/009100); Osteichthyes (/content/osteichthyes/478500) Fig. 1 Cladogram showing the relationships of the extant teleosts with the other extant actinopterygians. (J. S. Nelson, Fishes of the World, 4th ed., Wiley, New York, 2006) 1 of 9 10/7/2015 1:07 PM Teleostei - AccessScience from McGraw-Hill Education http://www.accessscience.com/content/teleostei/680400 Morphology Much of the evidence for teleost monophyly (evolving from a common ancestral form) and relationships comes from the caudal skeleton and concomitant acquisition of a homocercal tail (upper and lower lobes of the caudal fin are symmetrical). This type of tail primitively results from an ontogenetic fusion of centra (bodies of vertebrae) and the possession of paired bracing bones located bilaterally along the dorsal region of the caudal skeleton, derived ontogenetically from the neural arches (uroneurals) of the ural (tail) centra. -

CHECKLIST and BIOGEOGRAPHY of FISHES from GUADALUPE ISLAND, WESTERN MEXICO Héctor Reyes-Bonilla, Arturo Ayala-Bocos, Luis E

ReyeS-BONIllA eT Al: CheCklIST AND BIOgeOgRAphy Of fISheS fROm gUADAlUpe ISlAND CalCOfI Rep., Vol. 51, 2010 CHECKLIST AND BIOGEOGRAPHY OF FISHES FROM GUADALUPE ISLAND, WESTERN MEXICO Héctor REyES-BONILLA, Arturo AyALA-BOCOS, LUIS E. Calderon-AGUILERA SAúL GONzáLEz-Romero, ISRAEL SáNCHEz-ALCántara Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada AND MARIANA Walther MENDOzA Carretera Tijuana - Ensenada # 3918, zona Playitas, C.P. 22860 Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Sur Ensenada, B.C., México Departamento de Biología Marina Tel: +52 646 1750500, ext. 25257; Fax: +52 646 Apartado postal 19-B, CP 23080 [email protected] La Paz, B.C.S., México. Tel: (612) 123-8800, ext. 4160; Fax: (612) 123-8819 NADIA C. Olivares-BAñUELOS [email protected] Reserva de la Biosfera Isla Guadalupe Comisión Nacional de áreas Naturales Protegidas yULIANA R. BEDOLLA-GUzMáN AND Avenida del Puerto 375, local 30 Arturo RAMíREz-VALDEz Fraccionamiento Playas de Ensenada, C.P. 22880 Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Ensenada, B.C., México Facultad de Ciencias Marinas, Instituto de Investigaciones Oceanológicas Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, Carr. Tijuana-Ensenada km. 107, Apartado postal 453, C.P. 22890 Ensenada, B.C., México ABSTRACT recognized the biological and ecological significance of Guadalupe Island, off Baja California, México, is Guadalupe Island, and declared it a Biosphere Reserve an important fishing area which also harbors high (SEMARNAT 2005). marine biodiversity. Based on field data, literature Guadalupe Island is isolated, far away from the main- reviews, and scientific collection records, we pres- land and has limited logistic facilities to conduct scien- ent a comprehensive checklist of the local fish fauna, tific studies. -

Acanthopterygii, Bone, Eurypterygii, Osteology, Percomprpha

Research in Zoology 2014, 4(2): 29-42 DOI: 10.5923/j.zoology.20140402.01 Comparative Osteology of the Jaws in Representatives of the Eurypterygian Fishes Yazdan Keivany Department of Natural Resources (Fisheries Division), Isfahan University of Technology, Isfahan, 84156-83111, Iran Abstract The osteology of the jaws in representatives of 49 genera in 40 families of eurypterygian fishes, including: Aulopiformes, Myctophiformes, Lampridiformes, Polymixiiformes, Percopsiformes, Mugiliformes, Atheriniformes, Beloniformes, Cyprinodontiformes, Stephanoberyciformes, Beryciformes, Zeiformes, Gasterosteiformes, Synbranchiformes, Scorpaeniformes (including Dactylopteridae), and Perciformes (including Elassomatidae) were studied. Generally, in this group, the upper jaw consists of the premaxilla, maxilla, and supramaxilla. The lower jaw consists of the dentary, anguloarticular, retroarticular, and sesamoid articular. In higher taxa, the premaxilla bears ascending, articular, and postmaxillary processes. The maxilla usually bears a ventral and a dorsal articular process. The supramaxilla is present only in some taxa. The dentary is usually toothed and bears coronoid and posteroventral processes. The retroarticular is small and located at the posteroventral corner of the anguloarticular. Keywords Acanthopterygii, Bone, Eurypterygii, Osteology, Percomprpha following method for clearing and staining bone and 1. Introduction cartilage provided in reference [18]. A camera lucida attached to a Wild M5 dissecting stereomicroscope was used Despite the introduction of modern techniques such as to prepare the drawings. The bones in the first figure of each DNA sequencing and barcoding, osteology, due to its anatomical section are arbitrarily shaded and labeled and in reliability, still plays an important role in the systematic the others are shaded in a consistent manner (dark, medium, study of fishes and comprises a major percent of today’s and clear) to facilitate comparison among the taxa. -

Crestfish Lophotus Lacepede (Giorna, 1809) and Scalloped Ribbonfish Zu Cristatus (Bonelli, 1819) in the Northern Coast of Sicily, Italy

ISSN: 0001-5113 ACTA ADRIAT., ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC PAPER AADRAY 58(1): 137 - 146, 2017 Occurrence of two rare species from order Lampriformes: Crestfish Lophotus lacepede (Giorna, 1809) and scalloped ribbonfish Zu cristatus (Bonelli, 1819) in the northern coast of Sicily, Italy Fabio FALSONE1, Michele Luca GERACI1, Danilo SCANNELLA1, Charles Odilichukwu R. OKPALA1, Giovan Battista GIUSTO1, Mar BOSCH-BELMAR2, Salvatore GANCITANO1 and Gioacchino BONO1 1Institute for the Coastal Marine Environment, IAMC‑CNR, 91026 Mazara del Vallo, Sicily, Italy 2Consorzio Nazionale Interuniversitario per le Scienze del Mare (CoNISMa), Rome, Italy Corresponding author, e‑mail: [email protected] The bony fish Lophotus lacepede (Giorna, 1809) and Zu cristatus (Bonelli, 1819) are the two species rarely recorded within the Mediterranean basin, usually reported as accidentally captured in depth (mesopelagic) fishing operations. In the current work, we present the first record of L. lacepede and Z. cristatus in fishing catches from southwestern Tyrrhenian Sea. Moreover, in order to improve existent biological/ecological knowledge, some bio-related aspects such as feeding aspect, sexual maturity and age estimate have been discussed. Key words: crestfish, scalloped ribbonfish, meristic features, vertebrae, growth ring INTRODUCTION species of Lophotidae family, the L. lacepede inhabits the epipelagic zone, although it could The target species of this study (Lophotus also be recorded in most oceans from the surface lacepede and Zu cristatus) belong to Lophotidae up to 1000 m depth (HEEMSTRA, 1986; PALMER, (Bonaparte, 1845) and Trachipteridae (Swain- 1986; OLNEY, 1999). First record of this spe- son, 1839) families respectively, including the cies in the Mediterranean Basin was from the Lampriformes order (consisted of 7 families). -

Updated Checklist of Marine Fishes (Chordata: Craniata) from Portugal and the Proposed Extension of the Portuguese Continental Shelf

European Journal of Taxonomy 73: 1-73 ISSN 2118-9773 http://dx.doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2014.73 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2014 · Carneiro M. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Monograph urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:9A5F217D-8E7B-448A-9CAB-2CCC9CC6F857 Updated checklist of marine fishes (Chordata: Craniata) from Portugal and the proposed extension of the Portuguese continental shelf Miguel CARNEIRO1,5, Rogélia MARTINS2,6, Monica LANDI*,3,7 & Filipe O. COSTA4,8 1,2 DIV-RP (Modelling and Management Fishery Resources Division), Instituto Português do Mar e da Atmosfera, Av. Brasilia 1449-006 Lisboa, Portugal. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 3,4 CBMA (Centre of Molecular and Environmental Biology), Department of Biology, University of Minho, Campus de Gualtar, 4710-057 Braga, Portugal. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] * corresponding author: [email protected] 5 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:90A98A50-327E-4648-9DCE-75709C7A2472 6 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:1EB6DE00-9E91-407C-B7C4-34F31F29FD88 7 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:6D3AC760-77F2-4CFA-B5C7-665CB07F4CEB 8 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:48E53CF3-71C8-403C-BECD-10B20B3C15B4 Abstract. The study of the Portuguese marine ichthyofauna has a long historical tradition, rooted back in the 18th Century. Here we present an annotated checklist of the marine fishes from Portuguese waters, including the area encompassed by the proposed extension of the Portuguese continental shelf and the Economic Exclusive Zone (EEZ). The list is based on historical literature records and taxon occurrence data obtained from natural history collections, together with new revisions and occurrences. -

Constraints on the Timescale of Animal Evolutionary History

Palaeontologia Electronica palaeo-electronica.org Constraints on the timescale of animal evolutionary history Michael J. Benton, Philip C.J. Donoghue, Robert J. Asher, Matt Friedman, Thomas J. Near, and Jakob Vinther ABSTRACT Dating the tree of life is a core endeavor in evolutionary biology. Rates of evolution are fundamental to nearly every evolutionary model and process. Rates need dates. There is much debate on the most appropriate and reasonable ways in which to date the tree of life, and recent work has highlighted some confusions and complexities that can be avoided. Whether phylogenetic trees are dated after they have been estab- lished, or as part of the process of tree finding, practitioners need to know which cali- brations to use. We emphasize the importance of identifying crown (not stem) fossils, levels of confidence in their attribution to the crown, current chronostratigraphic preci- sion, the primacy of the host geological formation and asymmetric confidence intervals. Here we present calibrations for 88 key nodes across the phylogeny of animals, rang- ing from the root of Metazoa to the last common ancestor of Homo sapiens. Close attention to detail is constantly required: for example, the classic bird-mammal date (base of crown Amniota) has often been given as 310-315 Ma; the 2014 international time scale indicates a minimum age of 318 Ma. Michael J. Benton. School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1RJ, U.K. [email protected] Philip C.J. Donoghue. School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1RJ, U.K. [email protected] Robert J. -

Systematics and Evolution of the Genus Pleurothallis R. Br

Systematics and evolution of the genus Pleurothallis R. Br. (Orchidaceae) in the Greater Antilles DISSERTATION zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor rerum naturalium (Dr. rer. nat.) im Fach Biologie eingereicht an der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät I der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin von Diplom-Biologe Hagen Stenzel geb. 05.10.1967 in Berlin Präsident der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Prof. Dr. J. Mlynek Dekan der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät I Prof. Dr. M. Linscheid Gutachter/in: 1. Prof. Dr. E. Köhler 2. HD Dr. H. Dietrich 3. Prof. Dr. J. Ackerman Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 06.02.2004 Pleurothallis obliquipetala Acuña & Schweinf. Für Jakob und Julius, die nichts unversucht ließen, um das Zustandekommen dieser Arbeit zu verhindern. Zusammenfassung Die antillanische Flora ist eine der artenreichsten der Erde. Trotz jahrhundertelanger floristischer Forschung zeigen jüngere Studien, daß der Archipel noch immer weiße Flecken beherbergt. Das trifft besonders auf die Familie der Orchideen zu, deren letzte Bearbeitung für Cuba z.B. mehr als ein halbes Jahrhundert zurückliegt. Die vorliegende Arbeit basiert auf der lang ausstehenden Revision der Orchideengattung Pleurothallis R. Br. für die Flora de Cuba. Mittels weiterer morphologischer, palynologischer, molekulargenetischer, phytogeographischer und ökologischer Untersuchungen auch eines Florenteils der anderen Großen Antillen wird die Genese der antillanischen Pleurothallis-Flora rekonstruiert. Der Archipel umfaßt mehr als 70 Arten dieser Gattung, wobei die Zahlen auf den einzelnen Inseln sehr verschieden sind: Cuba besitzt 39, Jamaica 23, Hispaniola 40 und Puerto Rico 11 Spezies. Das Zentrum der Diversität liegt im montanen Dreieck Ost-Cuba – Jamaica – Hispaniola, einer Region, die 95 % der antillanischen Arten beherbergt, wovon 75% endemisch auf einer der Inseln sind. -

The Influence of Depth on Mercury Levels in Pelagic Fishes and Their Prey

The influence of depth on mercury levels in pelagic fishes and their prey C. Anela Choya,1, Brian N. Poppb, J. John Kanekoc, and Jeffrey C. Drazena aDepartment of Oceanography, University of Hawaii, 1000 Pope Road, Honolulu, HI 96822; bDepartment of Geology and Geophysics, University of Hawaii, 1680 East-West Road, Honolulu, HI 96822; and cPacMar Inc., 3615 Harding Avenue, Suite 409, Honolulu, HI 96816 Edited by David M. Karl, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI, and approved June 23, 2009 (received for review January 21, 2009) Mercury distribution in the oceans is controlled by complex bio- temperature, algal concentrations) (11), and perhaps most com- geochemical cycles, resulting in retention of trace amounts of this monly, size (12). Despite extensive measurements of mercury in metal in plants and animals. Inter- and intra-specific variations in both the environment and biota, it is still not known why, mercury levels of predatory pelagic fish have been previously irrespective of size, some fish species have elevated mercury linked to size, age, trophic position, physical and chemical envi- concentrations and others do not. ronmental parameters, and location of capture; however, consid- Biogeochemical studies detailing the movement of mercury erable variation remains unexplained. In this paper, we focus on between air, land, and ocean reservoirs have offered insight into differences in ecology, depth of occurrence, and total mercury where mercury may be distributed in the marine environment levels in 9 species of commercially important -

Anatomical Considerations of Pectoral Swimming in the Opah, Lampris Guttatus Author(S): Richard H

Anatomical Considerations of Pectoral Swimming in the Opah, Lampris guttatus Author(s): Richard H. Rosenblatt and G. David Johnson Source: Copeia, Vol. 1976, No. 2 (May 17, 1976), pp. 367-370 Published by: American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1443963 Accessed: 02/06/2010 14:24 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=asih. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Copeia. http://www.jstor.org ICHTHYOLOGICAL NOTES 367 (1936). -

Taxonomic Research of the Gobioid Fishes (Perciformes: Gobioidei) in China

KOREAN JOURNAL OF ICHTHYOLOGY, Vol. 21 Supplement, 63-72, July 2009 Received : April 17, 2009 ISSN: 1225-8598 Revised : June 15, 2009 Accepted : July 13, 2009 Taxonomic Research of the Gobioid Fishes (Perciformes: Gobioidei) in China By Han-Lin Wu, Jun-Sheng Zhong1,* and I-Shiung Chen2 Ichthyological Laboratory, Shanghai Ocean University, 999 Hucheng Ring Rd., 201306 Shanghai, China 1Ichthyological Laboratory, Shanghai Ocean University, 999 Hucheng Ring Rd., 201306 Shanghai, China 2Institute of Marine Biology, National Taiwan Ocean University, Keelung 202, Taiwan ABSTRACT The taxonomic research based on extensive investigations and specimen collections throughout all varieties of freshwater and marine habitats of Chinese waters, including mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan, which involved accounting the vast number of collected specimens, data and literature (both within and outside China) were carried out over the last 40 years. There are totally 361 recorded species of gobioid fishes belonging to 113 genera, 5 subfamilies, and 9 families. This gobioid fauna of China comprises 16.2% of 2211 known living gobioid species of the world. This report repre- sents a summary of previous researches on the suborder Gobioidei. A recently diagnosed subfamily, Polyspondylogobiinae, were assigned from the type genus and type species: Polyspondylogobius sinen- sis Kimura & Wu, 1994 which collected around the Pearl River Delta with high extremity of vertebral count up to 52-54. The undated comprehensive checklist of gobioid fishes in China will be provided in this paper. Key words : Gobioid fish, fish taxonomy, species checklist, China, Hong Kong, Taiwan INTRODUCTION benthic perciforms: gobioid fishes to evolve and active- ly radiate. The fishes of suborder Gobioidei belong to the largest The gobioid fishes in China have long received little group of those in present living Perciformes. -

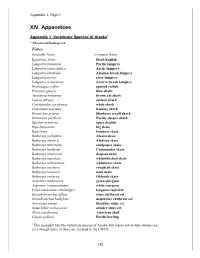

XIV. Appendices

Appendix 1, Page 1 XIV. Appendices Appendix 1. Vertebrate Species of Alaska1 * Threatened/Endangered Fishes Scientific Name Common Name Eptatretus deani black hagfish Lampetra tridentata Pacific lamprey Lampetra camtschatica Arctic lamprey Lampetra alaskense Alaskan brook lamprey Lampetra ayresii river lamprey Lampetra richardsoni western brook lamprey Hydrolagus colliei spotted ratfish Prionace glauca blue shark Apristurus brunneus brown cat shark Lamna ditropis salmon shark Carcharodon carcharias white shark Cetorhinus maximus basking shark Hexanchus griseus bluntnose sixgill shark Somniosus pacificus Pacific sleeper shark Squalus acanthias spiny dogfish Raja binoculata big skate Raja rhina longnose skate Bathyraja parmifera Alaska skate Bathyraja aleutica Aleutian skate Bathyraja interrupta sandpaper skate Bathyraja lindbergi Commander skate Bathyraja abyssicola deepsea skate Bathyraja maculata whiteblotched skate Bathyraja minispinosa whitebrow skate Bathyraja trachura roughtail skate Bathyraja taranetzi mud skate Bathyraja violacea Okhotsk skate Acipenser medirostris green sturgeon Acipenser transmontanus white sturgeon Polyacanthonotus challengeri longnose tapirfish Synaphobranchus affinis slope cutthroat eel Histiobranchus bathybius deepwater cutthroat eel Avocettina infans blackline snipe eel Nemichthys scolopaceus slender snipe eel Alosa sapidissima American shad Clupea pallasii Pacific herring 1 This appendix lists the vertebrate species of Alaska, but it does not include subspecies, even though some of those are featured in the CWCS.