Finessing for the Queen of Trumps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Normal Heart

THE NORMAL HEART Written By Larry Kramer Final Shooting Script RYAN MURPHY TELEVISION © 2013 Home Box Office, Inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No portion of this script may be performed, published, reproduced, sold or distributed by any means or quoted or published in any medium, including on any website, without the prior written consent of Home Box Office. Distribution or disclosure of this material to unauthorized persons is prohibited. Disposal of this script copy does not alter any of the restrictions previously set forth. 1 EXT. APPROACHING FIRE ISLAND PINES. DAY 1 Masses of beautiful men come towards the camera. The dock is full and the boat is packed as it disgorges more beautiful young men. NED WEEKS, 40, with his dog Sam, prepares to disembark. He suddenly puts down his bag and pulls off his shirt. He wears a tank-top. 2 EXT. HARBOR AT FIRE ISLAND PINES. DAY 2 Ned is the last to disembark. Sam pulls him forward to the crowd of waiting men, now coming even closer. Ned suddenly puts down his bag and puts his shirt back on. CRAIG, 20s and endearing, greets him; they hug. NED How you doing, pumpkin? CRAIG We're doing great. 3 EXT. BRUCE NILES'S HOUSE. FIRE ISLAND PINES. DAY 3 TIGHT on a razor shaving a chiseled chest. Two HANDSOME guys in their 20s -- NICK and NINO -- are on the deck by a pool, shaving their pecs. They are taking this very seriously. Ned and Craig walk up, observe this. Craig laughs. CRAIG What are you guys doing? NINO Hairy is out. -

HORSE out of TRAINING, Consigned by Godolphin

HORSE OUT OF TRAINING, consigned by Godolphin Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Somerville Paddock S, Box 358 Danzig (USA) Danehill (USA) 154 (WITH VAT) Razyana (USA) Dansili (GB) Kahyasi DUBRAVA (GB) Hasili (IRE) Kerali (2016) Doyoun A Grey Filly Daylami (IRE) Rose Diamond (IRE) Daltawa (IRE) (2006) Barathea (IRE) Tante Rose (IRE) My Branch (GB) DUBRAVA (GB): won 1 race at 3 years, 2019 and placed 3 times. Highest BHA rating 78 (Flat) Latest BHA rating 78 (Flat) (prior to compilation) TURF 3 runs ALL WEATHER 5 runs 1 win 3 pl £7,896 SS 7f 1st Dam Rose Diamond (IRE), won 2 races at 2 and 3 years at home and in U.S.A. and £60,016 and placed 5 times including second in Toteswinger Prestige Stakes, Goodwood, Gr.3; dam of three winners from 5 runners and 5 foals of racing age viz- REAL SMART (USA) (2012 f. by Smart Strike (CAN)), won 3 races at 3 and 4 years at home and in U.S.A. and £128,283 including Robert G Dick Memorial Stakes, Delaware Park, Gr.3, placed 5 times. TO DIBBA (GB) (2014 g. by Dubawi (IRE)), won 1 race at 3 years and £20,218 and placed 6 times. DUBRAVA (GB) (2016 f. by Dansili (GB)), see above. Rich Identity (GB) (2015 g. by Dubawi (IRE)), placed 4 times at 2 and 3 years. One Idea (GB) (2017 c. by Dubawi (IRE)), placed once at 2 years, 2019. (2018 c. by Dubawi (IRE)). She also has a 2019 filly by Postponed (IRE). -

Historical Bronzes Catalogue

Historical Bronzes by Fernando Andrea Table of Contents FERNANDO ANDREA ......................................................................................... 5 BRONZE-01 “General Custer (Son of the Morning Star)” ......................... 6 P.BRONZE-01 “General Custer Polychromed Bronze” ............................. 10 BRONZE-02 “Lawrence of Arabia” ................................................................... 12 BRONZE-03 “Chasseur de la Garde” .............................................................. 16 BRONZE-04 “Napoléon à Fontainebleau” ................................................... 20 BRONZE-04S “Napoléon à Fontainebleau (small)” .................................... 24 BRONZE-05 “Le Capitaine, 1805” ............................ ........................................ 26 BRONZE-06 “Banner” .................................................. ........................................ 30 P.BRONZE-06 “Banner Polychromed Bronze” .... ........................................ 33 BRONZE-07 “Le Roi Soleil, 1701” ............................. ........................................ 34 BRONZE-08 “Officier d’Artillerien de la Garde Impériale, 1809” .......... 38 NEWS ................................................................................ ........................................ 42 WORKSHOP ................................................................... ........................................ 44 Fernando Andrea He was born in Madrid, Spain, in 1961 and Fernando is also an accomplished musician received his early -

The Eclectic Club

The Eclectic Club Contents Part One The Structure of the Opening Bids Page 3 Part Two Responder’s First Bid 4 The Opening Bid of 1D 4 The Opening Bid of 1H 4 The Opening Bid of 1S 5 The Opening Bid of 1NT 5 Responding in a Minor 7 1NT is Doubled 7 The Rebid of 1NT 8 The Opening Bid of 2C 9 The Opening Bid of 2D 10 The Opening Bid of 2H/2S 11 The Opening Bid of 2NT 14 Part Three Splinters 14 Slam Splinters 14 The Residual Point Count 15 The Gap Between 16 1S 3H 17 Part Four Transfers and Relays 17 Let the Weak Hand Choose Trumps 17 The Competitive Zone 17 Bidding a Passed Hand 18 Transfers in Response to 1H and 1S 18 Transfer Response to 2C 20 The 5-3 Major Fit 21 The Cost of Transfers 21 Responder Makes Two Bids 22 Responder has Hearts 24 The Transfer to Partner’s Suit 25 The Shape Ask 27 Part Five The Control Ask 28 Florentine Blackwood 28 Blackwood with a Minor Suit Agreed 30 Part Six Strong Hands 31 The Opening Bid of 1C 31 Strong Balanced Hands 32 Strong Unbalanced Hands 32 Strong Two Suiters 32 The Golden Negatives 33 Special Positives 33 Opponents Bid over Our 1C 34 R.H.O Bids 35 Our Defence to Their 1C 36 Part Seven More Bidding Techniques 36 Canape in the Majors 36 Sputnik with a One Club System 37 Appendix The Variable Forcing Pass 39 A voyage of Discovery 39 Our Version of V.F.P. -

Chestnut Filly 1St Dam WAKIGLOTE, by Sandwaki

KILIA Chestnut filly Foaled 2019 Green Desert.................. by Danzig........................ (SIRE) Oasis Dream ................... Hope............................... by Dancing Brave............ DE TREVILLE............... Singspiel (Ire)................. by In the Wings .............. Dar Re Mi........................ Darara ............................ by Top Ville..................... (DAM) Dixieland Band ............... by Northern Dancer........ Sandwaki ........................ WAKIGLOTE................ Wakigoer........................ by Miswaki...................... 2011 Poliglote.......................... by Sadler's Wells............. Aurabelle......................... Nessara .......................... by Lashkari...................... DE TREVILLE (GB) (Bay 2012-Stud 2018). 2 wins-1 at 2-at 1400m, 1950m, €96,500, US$690, Longchamp Prix du Grand Palais, Chantilly Prix Vaublanc, 2d Chantilly Prix de Guiche, Longchamp Prix des Chenes, Prix de la Porte Maillot, Chantilly Prix de la Piste Rodosto, 3d Chantilly Prix Paul de Moussac. Sire. Half-brother to TOO DARN HOT (Goodwood Sussex S., Gr.1, Newmarket Dewhurst S., Gr.1), LAH TI DAR (York Middleton S., Gr.2, 2d The St Leger, Gr.1) and SO MI DAR (York Musidora S., Gr.3, 3d Chantilly Prix de l'Opera, Gr.1). Sire of Diadema, etc. His oldest progeny are 2YOs. 1st Dam WAKIGLOTE, by Sandwaki. Winner at 1400m, Chantilly Prix Chantilly Jumping. Dam of 4 foals, 2 to race. 2nd Dam AURABELLE, by Poliglote. 4 wins from 2000m to 2400m. Dam of 8 foals, 6 to race, 4 winners, inc:- Okabelle. 2 wins at 2, Chantilly Prix de Creil. Wakiglote. Winner. See above. Auraking. Winner at 1400m, 2d Deauville Prix de Maheru. Drosera Belle. 2 wins at 2400m, 2600m. Fortuite Rencontre. Placed at 2 in Kazakhstan. Kapaura. Placed. 3rd Dam NESSARA, by Lashkari. Raced twice. Half-sister to NESHAD, Poetry in Motion (dam of SESMEN). Dam of 2 foals, both winners- Aurabelle. -

I AM Because YOU ARE!

I AM Because YOU ARE! RJM TIMOR LESTE 06/09/2020- NEWSLETTER-03 With a firm commitment to alleviate the poor education, poverty incidence and all the accompanying social ills, the Sisters of the Religious of Jesus and Mary in Timor-Leste strive to devote their energy and resources to “ Educating for Life.” Thus began our story in the social sector of the courtry, in collaboration with the Jesuit Social Service. Br. Noel Oliver SJ and Sr. Mary Francis RJM with Mana Manuella began to respond to the needs of the women of Ulmera. The Tais groups were born in 2015. Soon the necessity for full time committement was felt and and in 2017 Sr. Vidya Pathare RJM stepped in as the Project Co- ordinator for Social Interventions. And so began the RJM- Jesuit venture. On 30th July 2019, the National Prison of Timor Leste granted permission to start rehabilitation and income generating programmes of weaving Tais for the female and handicrafts for the male inmates. Here are the success stories of two inmates interviewed by Sr. Vidya. I am Amer. I was in the military. I enjoyed my life with food, clothes, women and vices. My crime- I speculated that a neighbour used black magic and murdered my friend and in a state of drunkenness, I snatched the away the life of this woman, leading me to 18 years of imprisonment first in Becora Prison and then to Gleno. I am grateful for the on-anger management and music lessons I had in the prison. I met God in the prison especially in the Sisters and Priests who visited us. -

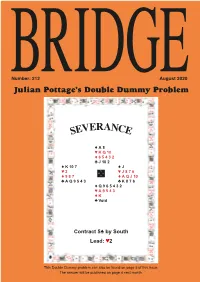

SEVERANCE © Mr Bridge ( 01483 489961

Number: 212 August 2020 BRIDGEJulian Pottage’s Double Dummy Problem VER ANCE SE ♠ A 8 ♥ K Q 10 ♦ 6 5 4 3 2 ♣ J 10 2 ♠ K 10 7 ♠ J ♥ N ♥ 2 W E J 8 7 6 ♦ 9 8 7 S ♦ A Q J 10 ♣ A Q 9 5 4 3 ♣ K 8 7 6 ♠ Q 9 6 5 4 3 2 ♥ A 9 5 4 3 ♦ K ♣ Void Contract 5♠ by South Lead: ♥2 This Double Dummy problem can also be found on page 5 of this issue. The answer will be published on page 4 next month. of the audiences shown in immediately to keep my Bernard’s DVDs would put account safe. Of course that READERS’ their composition at 70% leads straight away to the female. When Bernard puts question: if I change my another bidding quiz up on Mr Bridge password now, the screen in his YouTube what is to stop whoever session, the storm of answers originally hacked into LETTERS which suddenly hits the chat the website from doing stream comes mostly from so again and stealing DOUBLE DOSE: Part One gives the impression that women. There is nothing my new password? In recent weeks, some fans of subscriptions are expected wrong in having a retinue. More importantly, why Bernard Magee have taken to be as much charitable The number of occasions haven’t users been an enormous leap of faith. as they are commercial. in these sessions when warned of this data They have signed up for a By comparison, Andrew Bernard has resorted to his breach by Mr Bridge? website with very little idea Robson’s website charges expression “Partner, I’m I should add that I have of what it will look like, at £7.99 plus VAT per month — excited” has been thankfully 160 passwords according a ‘founder member’s’ rate that’s £9.59 in total — once small. -

''What Lips These Lips Have Kissed'': Refiguring the Politics of Queer Public Kissing

Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies Vol. 3, No. 1, March 2006, pp. 1Á/26 ‘‘What Lips These Lips Have Kissed’’: Refiguring the Politics of Queer Public Kissing Charles E. Morris III & John M. Sloop In this essay, we argue that man-on-man kissing, and its representations, have been insufficiently mobilized within apolitical, incremental, and assimilationist pro-gay logics of visibility. In response, we call for a perspective that understands man-on-man kissing as a political imperative and kairotic. After a critical analysis of man-on-man kissing’s relation to such politics, we discuss how it can be utilized as a juggernaut in a broader project of queer world making, and investigate ideological, political, and economic barriers to the creation of this queer kissing ‘‘visual mass.’’ We conclude with relevant implications regarding same-sex kissing and the politics of visible pleasure. Keywords: Same-Sex Kissing; Queer Politics; Public Sex; Gay Representation In general, one may pronounce kissing dangerous. A spark of fire has often been struck out of the collision of lips that has blown up the whole magazine of 1 virtue.*/Anonymous, 1803 Kissing, in certain figurations, has lost none of its hot promise since our epigraph was penned two centuries ago. Its ongoing transformative combustion may be witnessed in two extraordinarily divergent perspectives on its cultural representation and political implications. In 2001, queer filmmaker Bruce LaBruce offered in Toronto’s Eye Weekly a noteworthy rave of the sophomoric buddy film Dude, Where’s My Car? One scene in particular inspired LaBruce, in which we find our stoned protagonists Jesse (Ashton Kutcher) and Chester (Seann William Scott) idling at a stoplight next to superhunk Fabio and his equally alluring female passenger. -

Horse Motifs in Folk Narrative of the Supernatural

HORSE MOTIFS IN FOLK NARRATIVE OF THE SlPERNA TURAL by Victoria Harkavy A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Interdisciplinary Studies Committee: ___ ~C=:l!L~;;rtl....,19~~~'V'l rogram Director Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date: ~U_c-ly-=-a2..!-.:t ;LC>=-----...!/~'fF_ Spring Semester 2014 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Horse Motifs in Folk Narrative of the Supernatural A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at George Mason University by Victoria Harkavy Bachelor of Arts University of Maryland-College Park 2006 Director: Margaret Yocom, Professor Interdisciplinary Studies Spring Semester 2014 George Mason University Fairfax, VA This work is licensed under a creative commons attribution-noderivs 3.0 unported license. ii DEDICATION This is dedicated to my wonderful and supportive parents, Lorraine Messinger and Kenneth Harkavy. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my committee, Drs. Yocom, Fraser, and Rashkover, for putting in the time and effort to get this thesis finalized. Thanks also to my friends and colleagues who let me run ideas by them. Special thanks to Margaret Christoph for lending her copy editing expertise. Endless gratitude goes to my family taking care of me when I was focused on writing. Thanks also go to William, Folklore Horse, for all of the inspiration, and to Gumbie, Folklore Cat, for only sometimes sitting on the keyboard. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Abstract .............................................................................................................................. vi Interdisciplinary Elements of this Study ............................................................................. 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ -

Maria Marshall Au Affaire De Famille» Un Texte Sur Charles Des Médicis), La Nourriture, Il Nous Livre Dans Les Dynamisme Ambiant

Trimestriel d'actualité d'art contemporai n : avril.mail.juin 2013 • N°61 • 3 € L u c T u y m a n s , © F b B l u u e r x l e g N L a 9 ï e i e u / P è 2 - w B g . d 1 P s e e e 7 . l 0 X g d i é q p u ô e t Sommaire Edito « ... Et si je vieillis seule et sale je n’oublierai jamais dial. Dans ce cadre prestigieux où l’art et le luxe que l’Art est ma seule nourriture ». C’est la dernière sont rois, j’ai eu l’occasion de croiser un galeriste 2 Édito . Dogma, un projet de ville. Focus sur une strophe de l’autoportrait écrit à la main de Manon philosophe. Le galeriste NewYorkais m’a surpris agence d’architecture un peu particulière, 3 Michel Boulanger.Jalons, un texte de Bara qui fait la cover de FluxNews. Un élan sous par la teneur de son discours. Ironisant sur sa posi - par Carlo Menon. Yves Randaxhe. forme de rayon de soleil dans le petit monde de l’art tion de plus en plus marginalisée face à la montée en 21 Suite d’On Kawara par Véronique Per - d’aujourd’hui. La petite entreprise de Manon ne puissance d’une galerie comme Gagosian qui grâce 4 Concentration de galeries dans le haut riol. connaît pas la crise, elle carbure à l’essentiel... L’art à ses nombreuses succursales occupe plus de trois de Bruxelles, texte de Colette Dubois. -

PIAFFE in ENGLISH Totilas Or

PIAFFE IN ENGLISH magazine translation for the international reader 2010/1 magazine page 4 Totilas Or: Mr. Gal’s Big Appearance By Karin Schweiger took risks during his performance. Even though he could not prevent mistakes within Gold, silver, bronze – in 2009, the Dutch riders the flying changes at every stride, the entire decided the European championship dressage audience was enchanted by jet-black Totilas freestyle titles among themselves. Edward Gal and his prodigious movements. made history by achieving an all-time high of 90.70 points and opening the door to new His victory was a given and at no point in spheres of grading. The audience – and not danger. Totilas had earned it. 90.70 points! No just the Dutch spectators – was beyond itself one had believed this sound barrier could ever watching the battle between the three top be breached – it has been done, however. Gal contestants from the Netherlands. This was won gold which represents his first ever major the first time the stadium had ever been sold title. Dressage fans may decide for themselves out; tension could not have been built up in a if Erik Lette, president of the judges present, is more dramatic way: First, current winners of right by saying the following: “This was the the Classic Tour Adelinde Cornelissen and best competition we have ever seen. So many Parzival had to set the pace. Their great horses – and from various nations at performance included highstepping passages, that. It will prove beneficial for the future of a wonderfully impulsive extended trot and our sport.” All of the above is based on the rhythmic double pirouettes. -

Beauty and the Beast

BEAUTY AND THE BEAST A GRAND COMIC, ROMANTIC, OPERATIC, MELO-DRAMATIC, FAIR2 E3TRAVAGANZA. IN TWO ACTS B2 J. R. PLANCHE, ESQ. AUTHOR OF Fortunio — Blue Beard—Sleeping Beauty—Bee and the Orange Tree — Birds of Aristophanes—Drama at Home—Love and For- tune—Golden Fleece—Graciosa and Percinet—White Cat—Island of Jewels — King Charming — Theseus and Ariadne — Golden Branch—Invisible Prince—Fair One with the Golden Locks—Good Woman in the Wood—Buckstone's Ascent of Mount Parnassus— Buckstone's Voyage Round the Globe—Camp at the Olympic— Once upon a Time there were Two Kings— Yellow Dwarf—Cymon and Iphigenia—Prince of Happy Land—Queen of the Frogs—Seven Champions—Haymarket Spring Meeting—Discreet Princess— AND JOINTL2 OF The Deep, Deep Sea—Olympic Revels—Olympic Devils—Paphian Bower—Telemachus—Riquet with the Tuft—High Low Jack and the Game—Puss in Boots—Blue Beard, &c. &c. &c. LONDON. THOMAS HAILES LAC2, 89, STRAND, (Opposite Southampton Street, Covent Garden Market.) - , D A , , S Z A D , E N R R R . B A M A E . D , G A L BYRNE. W J N 1 T W A Z O 4 A . U V . T r 8 G L I B A N 1 , M F B , . R A T , , . y L J T T 2 R b OSBORNE. M . OSCAR L E 1 r . s X I O t O T L E N H L n M L L e . O Y D S Mr. Y O L S m E . S A t I R C L I L April n by T H R , i , A .