L0030 a Village History.Dtp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

York Clergy Ordinations 1374-1399

York Clergy Ordinations 1374-1399 Edited by David M. Smith 2020 www.york.ac.uk/borthwick archbishopsregisters.york.ac.uk Online images of the Archbishops’ Registers cited in this edition can be found on the York’s Archbishops’ Registers Revealed website. The conservation, imaging and technical development work behind the digitisation project was delivered thanks to funding from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Register of Alexander Neville 1374-1388 Register of Thomas Arundel 1388-1396 Sede Vacante Register 1397 Register of Robert Waldby 1397 Sede Vacante Register 1398 Register of Richard Scrope 1398-1405 YORK CLERGY ORDINATIONS 1374-1399 Edited by DAVID M. SMITH 2020 CONTENTS Introduction v Ordinations held 1374-1399 vii Editorial notes xiv Abbreviations xvi York Clergy Ordinations 1374-1399 1 Index of Ordinands 169 Index of Religious 249 Index of Titles 259 Index of Places 275 INTRODUCTION This fifth volume of medieval clerical ordinations at York covers the years 1374 to 1399, spanning the archiepiscopates of Alexander Neville, Thomas Arundel, Robert Waldby and the earlier years of Richard Scrope, and also including sede vacante ordinations lists for 1397 and 1398, each of which latter survive in duplicate copies. There have, not unexpectedly, been considerable archival losses too, as some later vacancy inventories at York make clear: the Durham sede vacante register of Alexander Neville (1381) and accompanying visitation records; the York sede vacante register after Neville’s own translation in 1388; the register of Thomas Arundel (only the register of his vicars-general survives today), and the register of Robert Waldby (likewise only his vicar-general’s register is now extant) have all long disappeared.1 Some of these would also have included records of ordinations, now missing from the chronological sequence. -

Index of Manuscripts

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-44420-0 - The Cambridge History of Medieval English Literature Edited by David Wallace Index More information Index of manuscripts Aberystwyth, National Library of Wales Durham Cathedral Library 6680: 195 b.111.32, f. 2: 72n26 c.iv.27: 42, 163n25 Cambridge, Corpus Christi College 32: 477 Edinburgh, National Library of Scotland 140: 461n28 Advocates 1.1.6 (Bannatyne MS): 252 145: 619 Advocates 18.7.21: 361 171: 234 Advocates 19.2.1 (Auchinleck MS): 91, 201: 853 167, 170–1, 308n42, 478, 624, 693, 402: 111 697 Cambridge, Gonville and Caius College Advocates 72.1.37 (Book of the Dean of 669/646: 513n2 Lismore): 254 Cambridge, Magdalene College Pepys 2006: 303n32, 308n42 Geneva, Fondation Martin Bodmer Pepys 2498: 479 Cod. Bodmer 168: 163n25 Cambridge, Trinity College b.14.52: 81n37 Harvard, Houghton Library b.15.18: 337n104 Eng 938: 51 o.3.11: 308n42 Hatfield House o.9.1: 308n42 cp 290: 528 o.9.38 (Glastonbury Miscellany): 326–7, 532 Lincoln Cathedral Library r.3.19: 308n42, 618 91: 509, 697 r.3.20: 59 London, British Library r.3.21: 303n32, 308n42 Additional 16165: 513n2, 526 Cambridge, University Library Additional 17492 (Devonshire MS): 807, Add. 2830: 387, 402–6 808 Add. 3035: 593n16 Additional 22283 (Simeon MS): 91, dd.1.17: 513n2, 515n6, 530 479n61 dd.5.64: 498 Additional 24062: 651 ff.4.42: 186 Additional 24202: 684 ff.6.17: 163n25 Additional 27879 (Percy Folio MS): 692, gg.1.34.2: 303n32 693–4, 702, 704, 708, 710–12, 718 gg.4.31: 513n2, 515n6 Additional 31042: 697 hh.1.5: 403n111 Additional 35287: -

THE UNIVERSITY of HULL John De Da1derby

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL John de Da1derby, Bishop 1300 of Lincoln, - 1320 being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Hull by Clifford Clubley, M. A. (Leeds) March, 1965 r' ý_ý ki "i tI / t , k, CONTENTS Page 1 Preface """ """ """ """ """ Early Life ... ... ... ... ... 2 11 The Bishop's Household ... ... ... ... Diocesan Administration ... ... ... ... 34 Churches 85 The Care of all the . ... ... ... Religious 119 Relations with the Orders. .. " ... Appendices, Dalderby's 188 A. Itinerary ... ... B. A Fragment of Dalderby's Ordination Register .. 210 C. Table of Appointments ... ... 224 ,ý. ý, " , ,' Abbreviations and Notes A. A. S. R. Reports of the Lincolnshire Associated architectural Archaeological Societies. and Cal. Calendar. C. C. R. Calendar of Close Rolls C. P. R. Calendar of Patent Rolls D&C. Dean and Chapter's Muniments E. H. R. English History Review J. E. H. Journal of Ecclesiastical History L. R. S. Lincoln Record Society O. H. S. Oxford Historical Society Reg. Register. Reg. Inst. Dalderby Dalderby's Register of Institutions, also known as Bishopts Register No. II. Reg. Mem. Dalderby Dalderby's Register of Memoranda, or Bishop's Register No. III. The folios of the Memoranda Register were originally numbered in Roman numerals but other manuscripts were inserted Notes, continued when the register was bound and the whole volume renumbered in pencil. This latter numeration is used in the references given in this study. The Vetus Repertorium to which reference is made in the text is a small book of Memoranda concerning the diocese of Lincoln in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. The original is in the Cambridge University Library, No. -

The Pre-Reformation Church

History of St Mary The Virgin Church, Purley on Thames The Pre-Reformation Church 3 The Pre-Reformation Church On the Record (1180-1280) Around 1185 we have a record of a gift of land in Purley to the Abbey of Reading by Isabella de Sifrewast. It is contained in a charter preserved in the cartulary of Reading Abbey. Isabella grants a half virgate of land (approx 15 acres) which was tenanted by Osbert, son of Godwyn the fisherman and his sons. We have identified this as the land between Purley Lane and Glebe Road and between the main road and north side of the Purley Lodge grounds. She left it to the Abbey to decide whether to allow Osbert to continue tenanting the land on the same terms. It seems the land remained in the hands of the Abbey until dissolution as when the assets of the Abbey were catalogued in 1538 there was a holding of land in Purley by William Fuller paying an annual rent of 6 shillings. One of the witnesses to Isabella’s Charter was John the chaplain and it is conceivable that he was acting as vicar of Purley at the time. In 1230 persons who qualified as ‘tenants-in-chief of the Church of Sarum’ were declared to be free of all tolls and other customs in Reading. The Lords of the Manor of both Purley Parva (William Sifrewast) and Purley Magna (Thomas Huscarle) were both specifically listed as exempt. The earliest record of the clergy in Purley was in 1248 when John, vicar of Purley, was in dispute with Roger of Hide over a quarter of an acre of pasture in Great Purley. -

The Reading Abbey Formulary (Berkshire Record Office, D/EZ 176/1)

The Reading Abbey Formulary (Berkshire Record Office, D/EZ 176/1) Brian Kemp University of Reading In 2013 the Berkshire Record Office took possession of a small, neat parchment volume, bound in eighteenth-century vellum, which has become known as the Reading Abbey Formulary. It constitutes one of the most important acquisitions made by the Record Office for many years, and I shall say more later about how it came about. Although one cannot be absolutely certain that it is from Reading Abbey—it does not, for example, bear the usual Reading Abbey ex libris inscription: ‘Hic est liber Sancte Marie de Rading’. Quem qui celaverit vel fraudem de eo fecerit anathema sit ’, or any other medieval mark of provenance1 - a close analysis of the contents shows beyond all doubt that it was compiled either in and for the abbey or, at least, for a lawyer or senior scribe working there. As such, it was one of the small handful of Reading Abbey manuscript volumes still in private hands before it was purchased by the Record Office. It is also the only major Reading Abbey manuscript ever acquired by the Record Office, and it is therefore fitting and gratifying that after nearly five centuries since the abbey’s dissolution it has returned to the town where it was created. A number of medieval English formularies survive from monasteries, cathedrals and other corporate bodies. They form a very varied group, both in structure and in content, and were certainly not compiled in accordance with a standard plan. As far as I know, all are unique with no duplicate copies.2 The Reading example is a most interesting and valuable addition to their number. -

A History of English Goldsmiths and Plateworkers

; 6HH G r~L D A AUBIF ABBOBUM. frjtoj of <fegl:b| (Solbsimtjjs anb |1httcborko, AND THEIR MARKS STAMPED ON PLATE P COPIED IN AC-SIMILE FROM CELEBRATED EXAMPLES J AND THE EARLIEST RECORDS PRESERVED AT GOLDSMITHS' HALL, LONDON, WITH THEIR NAMES, ADDRESSES, AND DATES OF ENTRY. 2,500 ILLUSTRATIONS. ALSO HISTORICAL ACCOUNTS OF THE GOLDSMITHS' COMPANY AND THEIR HALL MARKS; THE REGALIA; THE MINT; CLOSING OF THE EXCHEQUER GOLDSMITH-BANKERS; SHOP SIGNS; A COPIOUS INDEX, ETC. PRECEDED BY AN INTRODUCTORY ESSAY ON THE GOLDSMITHS' AET. BY WILLIAM CHAFFERS, AUTHOR OF " HALL MARKS ON GOLD AND SILVER PLATE," " L'ORFEVRERIE FRANCAISE," " MARKS AND MONOGRAMS ON POTTERY AND PORCELAIN " " THE KERAMIC GALLERY " (ILLUSTRATED), " THE COLLECTOR'S HANDBOOK OF MARKS AND MONOGRAMS ON POTTERY AND PORCELAIN," " PRICED CATALOGUE OF COINS," ETC. The Companion to "HALL MARKS ON GOLD AND SILVER PLATE," by the same Author. LONDON: W. H. ALLEN & CO., 13 WATERLOO PLACE. PUBLISHERS TO THE INDIA OFFICE. clo.Io.ccc.Lxxxin. All rights reserved.) : LONDON PRINTED BY W. H. ALL EX AND CO., 13 WATERLOO PLACE. 8.W. PKEFACE. The former work of the writer, entitled " Hall Marks on Gold and Silver Plate," has been so extensively patronised by the public as to call for six editions since the date of its first appearance in I860, supplying a most important aid to Ama- teurs and Collectors of Old Plate, enabling them to ascertain the precise date of manufacture by the sign manual of the Goldsmiths' Company, stamped upon it when sent to be assayed. That it has been generally appreciated is evident from the fact that it is to be found in the hands of every leading Goldsmith in the United Kingdom, as well as Amateurs and Possessors of family plate. -

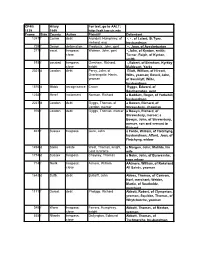

Sorted by Defendant

CP40/ Hilary For text, go to AALT: 1139 1549 http://aalt.law.uh.edu Frame Side County Action Plaintiff Defendant 1247 f Cornw debt Arundell, Humphrey, of -, - , of Lalant, St Tyes, Hellond, esq husbandman 729 f Devon defamation Predyaux, John, gent --, Joan, of Ayssheburton 277 f vacat trespass: Wolmer, John, gent -,John, of Kynton, smith; close Turner, Ralph, of Kynton, smith 193 f vacated trespass: Gresham, Richard, -,Robert, of Brimham, Kyrkby close knight Maldesert, Yorks 2021 d London debt Percy, John, of Eliott, William, of Hircott, Overbrigatte, Hants, Wilts, yeoman; Revell, John, yeoman of Swalclyff, Wilts, husbandman 1870 d Middx recognisance Crown Ryggs, Edward, of Southampton, gent 1238 f Heref incitement Norman, Richard a Baddam, Roger, of Yorkehill, husbandman 2227 d London debt Gyggs, Thomas, of a Bowen, Richard, of London, mercer Shrewsbury, chapman 976 f London debt Gyggs, Thomas, mercer a Bowyn, Richard, of Shrewsbury, mercer; a Bowyn, John, of Shrewsbury, mercer, son and servant to Richard 461 f Sussex trespass Gere, John a Forde, William, of Fletchyng, husbandman; Afford, Joan, of Fletchyng, widow 1494 d Soms waste West, Thomas, knight, a Morgan, John; Matilda, his Lord la Warre wife 1774 d Sussex trespass Cheyney, Thomas a Noke, John, of Burwasshe, rope mkaer 714 f Norfk trespass: Atmere, William AAtmere, William, of Rokeland close All Saints, yeoman 1643 d Suffk debt Buttolff, John Abbes, Thomas, of Cawson, Norf, merchant; Webbe, Martin, of Southolde, merchant 1171 f Dorset debt Phelypp, Richard Abbott, Robert, of -

The Episcopate of Walter Langton, Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield, 1296-1321

"THE EPISCOPATE OF WALTER LANGTON, BISHOP OF COVENTRY AND LICHFIELD, 1296-1321, WITH IA CALENDAR OF HIS REGISTER" by Jill Blackwell Hughes, BA Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, October, 1992. CONTENTS. ABSTRACT vi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS viii NOTE ON EDITORIAL METHOD x LISTS OF ABBREVIATIONS I. Words xii II. Publications, repositories and manuscripts xiv INTRODUCTION 1. The Register 1 I. The First Lichfield Episcopal Register 1 II. The Condition of the Register 8 III. The Structure of the Register 10 i. The First Four Folios 10 ii. The Arrangement of the Remainder of the Register 32 IV. The Marginalia 42 V. The Ordination Lists 44 VI. Licences for Non-Residence 73 2. The Diocese 84 I. The Extent of the Diocese 84 II. The Administration of the Diocese 88 i. The Local Administration 88 a. The Archdeaconries and Archdeacons 88 The Archdeaconry of Chester 91 The Archdeaconry of Coventry 101 ii The Archdeaconry of Derby 108 The Archdeaconry of Shrewsbury 115 The Archdeaconry of Stafford 119 b. The Rural Deans 122 C. Exempt Jurisdictions 127 ii. The Central Administration 134 a. The Vicars-General 134 b. The Chancellor 163 c. The Official 167 d. The Commissary-General and Sequestrator-General 172 III. The Administration of the Diocese during the Sequestration of the See, 30 March 1302 -8 June 1303 186 3. Walter Langton 198 I. Langton's Family Background 198 II. Langton's Early Career 213 III. Langton's Election as Bishop 224 IV. Langton, the Diplomat and Politician 229 V. Langton, the Bishop 268 VI. -

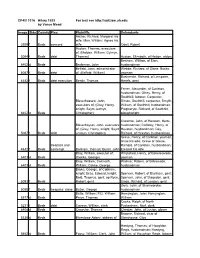

Sorted by County, Then Plaintiff

CP40/ 1076 Hilary 1533 For text see http://aalt.law.uh.edu by Vance Mead Image Side County Plea Plaintiffs Defendants Archer, Richard; Margaret his wife; Man, William; Agnes his 3929 f Beds concord wife Odell, Robert Aucton, Thomas, executors of; (Malden, William; Gylmyn, 5094 f Beds debt Thomas) Aucton, Elizabeth, of Hotton, widow Becham, William, of Eton, 6402 d Beds Barleman, John husbandman Belfeld, Joan, administrator Webbe, Richard, of Stone, Bucks, 5087 f Beds debt of; (Belfeld, William) yeoman Baskervile, Richard, of Lempster, 4482 f Beds debt execution Bently, Thomas Herefs, gent Ferrer, Alexander, of Carleton, husbandman; Olney, Henry, of Southhill, laborer; Carpenter, Bleverhassett, John, Simon, Southhill, carpenter; Smyth, executors of; (Grey, Henry, William, of Southhill, husbandman; knight; Seynt Jermyn, Ploghwryte, Richard, of Southhill, 6402 d Beds Christopher) ploughwright Crowche, John, of Hexston, Herts, Bleverhayset, John, executors husbandman; Coffeley, Henry, of of; (Grey, Henry, knight; Seynt Hexston, husbandman; Dey, 5087 f Beds debt Jermyn, Christopher) Richard, of Hexston, husbandman Greve, Henry, of Carleton, yeoman; Anne his wife; Greve or Grene, trespass and Richard, of Carleton, husbandman; 4632 f Beds contempt Bonham, thomas; Burell, John Eleanor his wife Bray, William, executor of; Whytehed, Henry, of Bekeleswade, 6403 d Beds (Cokke, George) yeoman Bray, William; Colmorth, Wolmar, Robert, of Beleswade, 6403 d Beds William; Cokke, George husbandman Broke, George, of Cobham, knight; Bray, Edward, knight; Spencer, -

1Recotbs Jbranch

WILTSHIRE ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY 1Recotbs JBranch VOLUME XVIII FOR THE YEAR 1962 CONTENTS Page CONTENTS V PREFACE vii TABLE o1= REFERENCES To THE PUB1.1c RECORDS ix TABLE OF ABBREv1AT1oNs ix INTRODUCTION THE MANUSCRIPT 3 THE SALISBURY CHAPTER 1329-49: PERSONNEL AND METHoDs OF RECRUITMENT 6 THE V1cABs-cHoRA1. 41 THE CHo1usTEBs 47 THE ‘CQMMUNA’ 49 EDITORIAL METHoD 58 I—IEM1NcBY’s REGISTER 59 B1ocBAPH1cA1. NoTEs I69 INDEX 261 LIST 01-" MEMBERS 28 1 PUBL1cATIoNs OF THE BRANCH 287 © Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society Records Branch 1963 Reprinted 1987 THIS VOLUME IS PUBLISHED WITH THE HELP OF A GRANT FROM THE LATE MISS ISOBEL THORNLEY'S BEQUEST TO THE UNIVERSITY OF LONDON. SET IN GRANION AND PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY PM PRINT WARMINSTER WILTSHIRE HEMINGBY’S REGISTER EDITED BY HELENA M. CHEW DEVIZES 963 PREFACE The Branch is indebted to the Dean an.d Chapter of Salisbury for permission to reproduce the text of this register and to Dr. A. E. I. Hollaender, of the Guildhall Library, London, in whose custody the manuscript remained for many months, with the chaptcr’s consent. It is also most particularly grateful to the Thornley Trustees and to the Governing Body of Queen Mary College in the University of London for making very valuable grants towards the costs of publication. The editor has asked that her sincere thanks may be recorded to Dr. Kathleen Edwards, at whose suggestion the edition was undertaken, and with whom she has had many helpful discussions while the work has been in progress; to Professor F. -

1 Felicity Hill in High and Late Medieval England, General Sentences Of

GENERAL EXCOMMUNICATIONS OF UNKNOWN MALEFACTORS: CONSCIENCE, COMMUNITY, AND INVESTIGATIONS IN ENGLAND, C. 1150-1350 Felicity Hill In high and late medieval England, general sentences of excommunication pronounced against unnamed wrongdoers were common. Responding to crimes where the perpetrators were unknown, general excommunications were a valuable tool that sought to discover and punish offenders in a number of ways. Solemn denunciations might convince the guilty to confess in order to avoid damnation, or persuade informants to volunteer information. General sentences were also, however, merely a precursor to investigations launched into those responsible. Public denunciations aided investigations conducted by clergy in the local community by publicising and forcibly condemning the crime committed. Once discovered, suspects were summoned to the bishop’s court and were either forced to make amends and do penance, or were excommunicated by name. This essay therefore argues that general sentences were far more complex, effective and legally significant than they are often perceived to be. In the 1160s,1 an old man was forced by necessity to sell some wood he owned. Being old and feeble, he entrusted the business of the sale to his adolescent son. The son, however, was greedy, defrauding his father by keeping most of the money from the sale for himself. Not suspecting his son, but certain that he had been wronged, the father asked his parish priest to bind with anathema ‘whoever had brought this loss upon him’. Three times the priest warned that he would pronounce the sentence, yet the son admitted nothing, publicly or privately. Finally the excommunication was pronounced, but still the son felt no remorse, disregarding the fact that Satan now possessed his body and soul. -

The Authorship of Ancren Riwle

THE AUTHORSHIP OF THE ANCREN RIWLE I Long before the English language reached the perfection bestowed upon it by the Bard of Avon it went through several stages in its development. The most important of these are marked by significant productions that stand like milestones along the road of progress. Thus, Caedmon sang in the last quar ter of the seventh century, Bede taught and wrote and prayed in the early eighth, Layamon composed his metrical chronicles in the thirteenth, and good old kindly· Chaucer portrayed and interpreted life in the fourteenth. These are the names around which we generally group our knowledge of the literary antiq uities of England. There is, however, another old monument with which we are less familiar. Its chronological place is just between Layamon and Chaucer. We ought to know it better, and appreciate it, too, for it is an excellent contribution to English in the formative pt!riod. It is a book entitled "Ancren Riwle," whose authorship has not as yet been definitely established. Though it is neither story, chronicle, poem nor drama, yet it is as interesting as a story, as important as a chronicle, and as beautiful as any poem or drama. The "Ancren Riwle," or "Anchoress' Rule," is simply a treatise on the spiritual life, a code of rules, written for the guidance of a small community of anchoresses. In the ages of faith we often find mention made of hermits, solitaries, anchorites, and anchoresses. The hermits and soli taries lived in huts and caves situated in the wilderness or in any place remote from inhabited regions.