NABMSA Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Js Battye Library of West Australian History Ephemera – Collection Listing

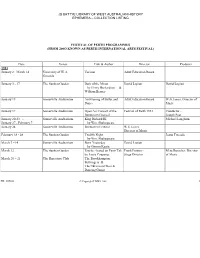

JS BATTYE LIBRARY OF WEST AUSTRALIAN HISTORY EPHEMERA – COLLECTION LISTING FESTIVAL OF PERTH PROGRAMMES (FROM 200O KNOWN AS PERTH INTERNATIONAL ARTS FESTIVAL) Date Venue Title & Author Director Producer 1953 January 2 - March 14 University of W.A. Various Adult Education Board Grounds January 3 - 17 The Sunken Garden Dark of the Moon David Lopian David Lopian by Henry Richardson & William Berney January 15 Somerville Auditorium An Evening of Ballet and Adult Education Board W.G.James, Director of Dance Music January 17 Somerville Auditorium Open Air Concert of the Festival of Perth 1953 Conductor - Beethoven Festival Joseph Post January 20-23 - Somerville Auditorium King Richard III Michael Langham January 27 - February 7 by Wm. Shakespeare January 24 Somerville Auditorium Beethoven Festival W.G.James Director of Music February 18 - 28 The Sunken Garden Twelfth Night Jeana Tweedie by Wm. Shakespeare March 3 –14 Somerville Auditorium Born Yesterday David Lopian by Garson Kanin March 12 The Sunken Garden Psyche - based on Fairy Tale Frank Ponton - Meta Russcher, Director by Louis Couperus Stage Director of Music March 20 – 21 The Repertory Club The Brookhampton Bellringers & The Ukrainian Choir & Dancing Group PR 10960 © Copyright LISWA 2001 1 JS BATTYE LIBRARY OF WEST AUSTRALIAN HISTORY PRIVATE ARCHIVES – COLLECTION LISTING March 25 The Repertory Theatre The Picture of Dorian Gray Sydney Davis by Oscar Wilde Undated His Majesty's Theatre When We are Married Frank Ponton - Michael Langham by J.B.Priestley Stage Director 1954.00 December 30 - March 20 Various Various Flyer January The Sunken Garden Peer Gynt Adult Education Board David Lopian by Henrik Ibsen January 7 - 31 Art Gallery of W.A. -

Tasmania Discovery Orchestra 2011 Concert 1

Tasmania Discovery Orchestra 2011 The Discovery Series, Season II Concert 1: Discover the Orchestra Alex Briger – Conductor Mozart Overture Die Zauberflöte , K. 620 Beethoven Symphony No. 7 in A Major, Op. 92 Coffee and Cake in the foyer with musicians and conductor Sunday 17 h April 2011 | 2:30pm Stanley Burbury Theatre Sandy Bay, Hobart The Tasmania Discovery Orchestra The TDO is a refreshingly new, bold idea in Australian orchestral music making, designed to offer musicians with advanced orchestral instrument skills the opportunity to come together and make great music in Hobart, Tasmania. The TDO was created in 2010, and was an immediate success, drawing musicians from around Australia to Hobart for the inaugural performance. The response for more performance opportunities for orchestral players is evident by the large number of TDO applicants for both the 2010 and 2011 seasons. This demand led to the creation of another new initiative by the Conservatorium of Music, the TDO Sinfonietta , which will be continuing in 2011. This ensemble performs the chamber music repertoire of the 20th- Century and works composed for mixed orchestral ensemble. With a repertoire of known favourites, this ensemble of more intimate proportions than the TDO, is designed for orchestral musicians with advanced chamber instrumental skills. The TDO and TDO Sinfonietta are about investing in the future of Australian music. Our mission is simple: Australian orchestral musicians, not employed in full-time positions with orchestras, need more opportunities to perform. We want our community and audience to get involved! Have you ever wondered how an orchestra works? Or, perhaps, you’ve always wanted to know what the Conductor does. -

Comments for Cds on Klassic Haus Website - January Releases Series 2013

Comments for CDs on Klassic Haus website - January Releases Series 2013 KHCD-2013-001 (STEREO) - Havergal Brian: Symphony No. 2 in E minor (1930-31) - BBC Symphony Orchestra/Sir Charles Mackerras - It is by now almost common knowledge among the cognoscenti of classical music that Havergal Brian (1876-1972) wrote 32 symphonies, starting with the enormous and still-controversial Gothic, and suffered decades of neglect. He was born in the same decade as composers like Ravel, Scriabin and Ralph Vaughan Williams, but his style belongs to no discernable school. Of course, he had his influences (Berlioz, Wagner, Elgar and Strauss spring to mind), but he digested them thoroughly and never really sounds like anyone else. Between 1900 and 1914, Brian briefly came to notice with a series of choral works and colourful symphonic poems. Then World War I broke out, and everything changed, not least his luck as a composer. But, although many decades of neglect lay in store for him, Brian found himself, too. By the end of World War II, therefore, he had written five symphonies, a Violin Concerto, an opera, The Tigers, and a big oratorio, Prometheus Unbound (the full score of which is still lost), all of them works of power and originality, and all of them unplayed for many years to come. Havergal Brian was already in his seventies. His life’s work was done, so it seemed. The opposite was the case. Symphony No. 2 in E minor was written in 1930-31. In it Brian tackles the purely instrumental symphony for the first time, after the choral colossus which is the Gothic. -

LP Auction Catalogue 120810-Web

Sale by Auction Mint Condition Lyrita LPs Lyrita Recorded Edition From the private archive of Lyrita Proprietor Richard Itter Lyrita Recorded Edition & Wyastone Estate Ltd are pleased to make available for sale by auction 97 titles from the original Lyrita LP catalogue. All copies come from the private archive of Lyrita’s founder and proprietor, Richard Itter. The LPs, which are all ‘Nimbus’ pressings, were Sale by Auction manufactured in the company’s Monmouth premises during the mid 1980s. Every LP is in its original sleeve. Mint Condition Lyrita LPs These examples have never been shipped for sale and have been stored upright in their factory boxes in dry, dark, temperate conditions since manufacture. th Closing date: 6 December 2010 This release of 1,987 LPs constitutes the major part of the Lyrita archive, only a handful of reference copies are being retained. Operation of the Auction The auction will open at 09.00 on 1 September 2010 and will close at 24.00 on 5 December 2010. Bids will only be accepted if made by post, fax or e-mail, an order form is attached to this catalogue. LPs will be allocated solely on the highest value bid. Successful bidders will be contacted after the auction has closed at which time we will confirm the allocation, calculate postage and collect payment details. Lyrita wishes to make these LPs widely available so will only allocate 1 example of any title per bid. However, in the event that all bids are satisfied and some LPs remain these will be allocated to any bidders requesting multiple copies and solely on the highest value bid. -

Delius (1862-1934)

BRITISH ORCHESTRAL MUSIC (Including Orchestral Poems, Suites, Serenades, Variations, Rhapsodies, Concerto Overtures etc) A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Frederick Delius (1862-1934) Born in Bradford to German parents. His family had not destined him for a musical career but due to the persuasion of Edvard Grieg his father allowed him to attend the Leipzig Conservatory where he was a pupil of Hans Sitt and Carl Reinecke. His true musical education, however, came from his exposure to the music of African-American workers in Florida as well as the influences of Grieg, Wagner and the French impressionists. His Concertos and other pieces in classical forms are not his typical works and he is best known for his nature-inspired short orchestral works. He also wrote operas that have yielded orchestral preludes and intermezzos in his most characteristic style. Sir Thomas Beecham was his great champion both during Delius’ lifetime and after his death. Air and Dance for String Orchestra (1915) Norman Del Mar/Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra ( + Elgar: Serenade for Strings, Vaughan Williams: Concerto Grosso and Warlock: Serenade) EMI CDM 565130-2 (1994) (original LP release: HMV ASD 2351) (1968) Vernon Handley/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Summer Evening, On Hearing the First Cuckoo in Spring, Summer Night on the River, Vaughan Williams: The Wasps Overture and Serenade to Music) CHANDOS CHAN 10174 (2004) (original CD release: CHANDOS CHAN 8330) (1985) Richard Hickox/Northern Sinfonia ( + Summer Evening, Winter Night, On Hearing the First Cuckoo in Spring, Summer Night on the River, A Song Before Sunrise, La Calinda, Hassan – Intermezzo and Serenade, Fennimore and Gerda – Intermezzo and Irmelin – Prelude) EMI BRITISH COMPOSERS CDM 5 65067 2 (1994) (original CD release: EMI CDC 7 47610 2) (1986) David Lloyd-Jones/English Northern Philharmonia ( + Bridge: Cherry Ripe, Sally in our Alley, Sir Roger de Coverley), Haydn Wood: Fantasy-Concerto, Ireland: The Holy Boy, Vaughan Williams: Charterhouse Suite, Elgar: Sospiri, Warlock: Serenade, G. -

2019 Sir Arnold Bax Programme

Australian Discovery Orchestra Managing Director: Janine Hanrahan 31 August & 1 September 2019 Sat. 31 August 7:00 pm Festival Opening The premiere screening of a new, interactive, short-film introducing the life of Sir Arnold Edward Trevor Bax (1883-1953). The film will also be available online immediately after the opening concert to allow exploration of all the interactive elements. 7:15 pm Pre-concert talk on the life of Sir Arnold Bax, discussing why this titan of 20th-Century British music and Master of the King’s Music has been inexplicably neglected on the concert stage over the last 60 years. Speaker: Kevin Purcell 7:45 pm Pro-Musica Orchestra – Conductor John Ferguson Arnold E. T. Bax Mediterranean for orchestra Edward Elgar Australia’s most innovative orchestra King Arthur Suite Conductor Kevin Purcell Sun. 1 September 11:00 am ADO Chamber Soloists Arnold E. T. Bax Frank Bridge Eugène Goosens Arnold E.T. Bax An Elegaic Trio Divertimenti Pastorale et Arlequinade Clarinet Sonata in D Major Soloist: Anne Brisk 2:30 am Australian Discovery Orchestra – Conductor Kevin Purcell Arnold E. T. Bax Edition 1 From Dusk ‘Till Dawn Ballet Suite Frank Bridge Lament (for Catherine, aged 9 "Lusitania" 1915) Arnold E. T. Bax Tintagel for orchestra All Day Festival Tickets from $15:00. Children under 15 years come for FREE! © Tintagel, Cornwall, UK BOOKINGS: https://australiandiscoveryorchestra.com/buy-tickets-ado-season-2019/ Ian Roach Hall | Scotch College | 1 Morrison Street, Hawthorn | 3122 Welcome to the inaugural, biennial, festival For all the lack of live performances of Bax’s works two celebrating the works of Sir Arnold Bax (1883 – record labels, predominantly, have been responsible for 1953). -

Melbourne Youth Orchestras 2019 Programs

Melbourne Youth Orchestras 2019 Programs Since 1967, Melbourne Youth Orchestras has been bringing young Victorian musicians together to participate in ensemble music-making. Our educational program continues to unleash creativity through inspiration and exploration, ultimately inspiring our members to reach their potential through music. Tens of thousands of students have taken part in our program, with many of our alumni fulfilling vital roles as leaders in music, the arts, business, and the community. We play a leadership role in collaborating with education and music partners to ensure that a high- quality music education is available for all students in Victoria. Our dream is that music is embraced and celebrated in Victoria, since it is instrumental in building community and developing the best in young people. Melbourne Youth Orchestras is recognised as one of Australia’s leading centres for ensemble music making and training, and a meeting place for young musicians and their families who travel from all over metropolitan and regional Victoria to participate. Photographs: Sarah Walker Welcome to our 2019 Program Guide Music inspires young people to reach their potential and Melbourne Youth Orchestras (MYO) is the place where young Victorians from a diversity of backgrounds come together for the joy of learning and playing music together. I welcome our new Music Director, Brett Kelly, to the MYO family. Brett brings a wealth of experience as a conductor and professional musician to MYO and his inaugural season for our flagship orchestra is sure to delight members and audiences alike. I am delighted that our partnerships with the Department of Education and Training, the Melbourne Conservatorium of Music and the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra will continue to enhance MYOʼs inspirational music program throughout 2019 and I encourage you to delve into our program guide and be a part of Melbourne Youth Orchestras in 2019. -

New Directions in Contemporary Music Theatre

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 1954-2016 University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1986 New directions in contemporary music theatre Lynette Frances Williams University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Williams, Lynette Frances, New directions in contemporary music theatre, Master of Arts (Hons.) thesis, School of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1986. https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/2260 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. -

British and Commonwealth Symphonies from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH SYMPHONIES FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers A-G KATY ABBOTT (b. 1971) She studied composition with Brenton Broadstock and Linda Kouvaras at the University of Melbourne where she received her Masters and PhD. In addition to composing, she teaches post-graduate composition as an onorary Fellow at University of Melbourne.Her body of work includes orchestral, chamber and vocal pieces. A Wind Symphony, Jumeirah Jane was written in 2008. Symphony No. 1 "Souls of Fire" (2004) Robert Ian Winstin//Kiev Philharmonic Orchestra (included in collection: "Masterworks of the New Era- Volume 12") ERM MEDIA 6827 (4 CDs) (2008) MURRAY ADASKIN (1905-2002) Born in Toronto. After extensive training on the violin he studied composition with John Weinzweig, Darius Milhaud and Charles Jones. He taught at the University of Saskatchewan where he was also composer-in-residence. His musical output was extensive ranging from opera to solo instrument pieces. He wrote an Algonquin Symphony in 1958, a Concerto for Orchestra and other works for orchestra. Algonquin Symphony (1958) Victor Feldbrill/Toronto Symphony Orchestra ( + G. Ridout: Fall Fair, Champagne: Damse Villageoise, K. Jomes: The Jones Boys from "Mirimachi Ballad", Chotem: North Country, Weinzweig: Barn Dance from "Red Ear of Corn" and E. Macmillan: À Saint-Malo) CITADEL CT-601 (LP) (1976) Ballet Symphony (1951) Geoffrey Waddington/Toronto Symphony Orchestra (included in collection: “Anthology Of Canadian Music – Murray Adaskin”) RADIO CANADA INTERNATIONAL ACM 23 (5 CDs) (1986) (original LP release: RADIO CANADA INTERNATIONAL RCI 71 (1950s) THOMAS ADÈS (b. -

The Delius Society Journal Winter/Spring 1996, Number 118

The Delius Society Journal Winter/Spring 1996, Number 118 The Delius Society Full Membership and Institutions £f 15 per year USA and Canada US$31 per year Mrica,Africa. Australasia and Far East £18tl8 President Eric Fenby OBE, Hon DMus.D Mus. Hon DLitt,D Litt, Hon RAM, FRCM, Hon FTCL Vice Presidents .F' Felixelix Aprahamian Hon RCO Roland GibsonGbson MSc, PhD (Founder Member) Meredith Davies CBE, MA, BMus,B Mus, FRCM, Hon RAM VemonVernon Handley MA,MAr FRCM, D Univ (Sorrey)(Suney) Richard Hickox FRCO (CHM) Rodney Meadows Chairman Lyndon Jenkins 3 Christchurch Close, Edgbaston, Birmingham BBl5 15 3NE TeI.Tel.(0121)(012r) 454 454715071s0 Treasurer (to whom membership enquiries should be directed) Derek Cox Mercers, 6 Mount Pleasant, Blockley, Glos GL56 9BU Tel: (01386) 700175 Secretary Jonathan Maddox 1I St Joseph's Close, Olney, Bucks. MK46 5HD TeI:Tel:(01234)(01234)7r34or 713401 Editor StepStephenhen Lloyd 82 FarIeyFarleyHill, Luton LUlLUI 5NR TeI:Tel: (01582) 200752007s CONTENTS The First American Essay on Delius by Robert Beckhard and Don Gillespie Gllespie. .....4 A Reluctant Apprentice: Delius and Chemnitz by Philip Jones.................. 17t7 Delius's Piano Concerto: The EarlyEarlv Three-Movement Version by Mike Ibbott.iUUott. 292s A Note on Watawa - Last of her Race? by Robert Thelfall.Thelfall.. .......... ..34 34 The Delius Association of Florida:Florida. 36th Annual Delius Festival by Henry Comely 35 Delius Society Meetings: John Amis on Grainger and Norman Del Mar..Mar. 38 Delius, GrezGrez and andthe Scandinavian ConnectionConnection.. ... ..... 40 SongsSongsof Farewell.Farewell...... 44 Midlands Branch Meetings: Delius andand La Belle Dame Sans MerciMerci............. 47 EJE J Moeran: A CentenaryCentenarvTalk. -

Elgar (1857-1934)

BRITISH ORCHESTRAL MUSIC (Including Orchestral Poems, Suites, Serenades, Variations, Rhapsodies, Concerto Overtures etc) A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934) Born in Broadheath, Worcestershire, Elgar was the son of a music shop owner and received only private musical instruction. Despite this he is arguably England's greatest composer some of whose orchestral music has traveled around the world more than any of his compatriots. In addition to the Symphonies, his Cello and Violin Concertos and Enigma Variations are his other orchestral masterpieces. His many other works for orchestra including the Pomp and Circumstance Marches, Falstaff and Cockaigne Overture have been recorded numerous times. He was appointed Master of the King's Musick in 1924. Adieu (orch. H. Geehl, 1932) George Hurst/Bournemouth Sinfonietta ( + Enigma Variations, Chanson de Matin, Chanson de Nuit, Sérénade Lyrique, Salut d'Amour, Dream Children, Contrasts, Soliloquy for Oboe and Orchestra, Caractacus - Woodland Interlude, Falstaff - 2 Interludes, Pomp and Circumstance Marches Nos. 1 - 5, Sospiri, Beau Brummel – Minuet, The Spanish Lady –Burlesco, 3 Bavarian Dances, The Starlight Express - Waltz and Sursum Corda) CHANDOS TWOFER CHAN 2414 (2 CDs) (1999) (original LP release: POLYDOR 2583 359) (1976) David Lloyd-Jones/BBC Concert Orchestra ( + Piano Concerto, So Many True Princesses, The Immortal Legions, Stars of the Summer Night, Collins: Elegy in Memory of Edward Elgar and Haydn Wood: Suite of Four Edward Elgar Songs). DUTTON EPOCH CDLX 7148 (2005) Air de Ballet (1887) David Lloyd-Jones/ BBC Concert Orchestra ( + Bavarian Dances, Sevillaña, Salut d’amour, Minuet, Chanson de Nuit, Chanson de Matin, Sérénade Lyrique – Mélodie, Mazurka, Serenade Mauresque, Introduction to Gavotte, Gavotte, May-Song, Canto Popolare, Pleading, Carissima, Rosemary, Mina, Jack Falstaff, page to the Duke of Norfolk’ and ‘Gloucestershire: Shallow’s Orchard) DUTTON EPOCH CDLX7354 (2018)’ Bavarian Dances (3), Op. -

An Evaluation of Orchestral Conducting Teaching Methods

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2011 Learning and teaching conducting through musical and non-musical skills: an evaluation of orchestral conducting teaching methods Jose Mauricio Valle Brandao Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Brandao, Jose Mauricio Valle, "Learning and teaching conducting through musical and non-musical skills: an evaluation of orchestral conducting teaching methods" (2011). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3954. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3954 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. LEARNING AND TEACHING CONDUCTING THROUGH MUSICAL AND NON-MUSICAL SKILLS: AN EVALUATION OF ORCHESTRAL CONDUCTING TEACHING METHODS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by José Maurício Valle Brandão B.M., Universidade Federal da Bahia, 1994 M. M., Universidade Federal da Bahia, 1999 Ph. D., Universidade Federal da Bahia, 2009 August, 2011 To my wife, Blandina; to my friend, Vladimir; to my advisor, Bill Grimes – none of you let me give up. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost I would like to acknowledge and thank the Louisiana State University and the Huel Perkins Fellowship for giving me the opportunity to study conducting in the United States.