Understanding Time and Causality Is the Key to Understanding Quantum Mechanics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Dynamical Triangulations

Introduction to Dynamical Triangulations Andrzej G¨orlich Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen Naxos, September 12th, 2011 Andrzej G¨orlich Causal Dynamical Triangulation Outline 1 Path integral for quantum gravity 2 Causal Dynamical Triangulations 3 Numerical setup 4 Phase diagram 5 Background geometry 6 Quantum fluctuations Andrzej G¨orlich Causal Dynamical Triangulation Path integral formulation of quantum mechanics A classical particle follows a unique trajectory. Quantum mechanics can be described by Path Integrals: All possible trajectories contribute to the transition amplitude. To define the functional integral, we discretize the time coordinate and approximate each path by linear pieces. space classical trajectory t1 time t2 Andrzej G¨orlich Causal Dynamical Triangulation Path integral formulation of quantum mechanics A classical particle follows a unique trajectory. Quantum mechanics can be described by Path Integrals: All possible trajectories contribute to the transition amplitude. To define the functional integral, we discretize the time coordinate and approximate each path by linear pieces. quantum trajectory space classical trajectory t1 time t2 Andrzej G¨orlich Causal Dynamical Triangulation Path integral formulation of quantum mechanics A classical particle follows a unique trajectory. Quantum mechanics can be described by Path Integrals: All possible trajectories contribute to the transition amplitude. To define the functional integral, we discretize the time coordinate and approximate each path by linear pieces. quantum trajectory space classical trajectory t1 time t2 Andrzej G¨orlich Causal Dynamical Triangulation Path integral formulation of quantum gravity General Relativity: gravity is encoded in space-time geometry. The role of a trajectory plays now the geometry of four-dimensional space-time. All space-time histories contribute to the transition amplitude. -

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry Jaap van Brakel Abstract: In this paper I assess the relation between philosophy of chemistry and (general) philosophy of science, focusing on those themes in the philoso- phy of chemistry that may bring about major revisions or extensions of cur- rent philosophy of science. Three themes can claim to make a unique contri- bution to philosophy of science: first, the variety of materials in the (natural and artificial) world; second, extending the world by making new stuff; and, third, specific features of the relations between chemistry and physics. Keywords : philosophy of science, philosophy of chemistry, interdiscourse relations, making stuff, variety of substances . 1. Introduction Chemistry is unique and distinguishes itself from all other sciences, with respect to three broad issues: • A (variety of) stuff perspective, requiring conceptual analysis of the notion of stuff or material (Sections 4 and 5). • A making stuff perspective: the transformation of stuff by chemical reaction or phase transition (Section 6). • The pivotal role of the relations between chemistry and physics in connection with the question how everything fits together (Section 7). All themes in the philosophy of chemistry can be classified in one of these three clusters or make contributions to general philosophy of science that, as yet , are not particularly different from similar contributions from other sci- ences (Section 3). I do not exclude the possibility of there being more than three clusters of philosophical issues unique to philosophy of chemistry, but I am not aware of any as yet. Moreover, highlighting the issues discussed in Sections 5-7 does not mean that issues reviewed in Section 3 are less im- portant in revising the philosophy of science. -

Causality and Determinism: Tension, Or Outright Conflict?

1 Causality and Determinism: Tension, or Outright Conflict? Carl Hoefer ICREA and Universidad Autònoma de Barcelona Draft October 2004 Abstract: In the philosophical tradition, the notions of determinism and causality are strongly linked: it is assumed that in a world of deterministic laws, causality may be said to reign supreme; and in any world where the causality is strong enough, determinism must hold. I will show that these alleged linkages are based on mistakes, and in fact get things almost completely wrong. In a deterministic world that is anything like ours, there is no room for genuine causation. Though there may be stable enough macro-level regularities to serve the purposes of human agents, the sense of “causality” that can be maintained is one that will at best satisfy Humeans and pragmatists, not causal fundamentalists. Introduction. There has been a strong tendency in the philosophical literature to conflate determinism and causality, or at the very least, to see the former as a particularly strong form of the latter. The tendency persists even today. When the editors of the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy asked me to write the entry on determinism, I found that the title was to be “Causal determinism”.1 I therefore felt obliged to point out in the opening paragraph that determinism actually has little or nothing to do with causation; for the philosophical tradition has it all wrong. What I hope to show in this paper is that, in fact, in a complex world such as the one we inhabit, determinism and genuine causality are probably incompatible with each other. -

Causality in Quantum Field Theory with Classical Sources

Causality in Quantum Field Theory with Classical Sources Bo-Sture K. Skagerstam1;a), Karl-Erik Eriksson2;b), Per K. Rekdal3;c) a)Department of Physics, NTNU, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, N-7491 Trondheim, Norway b) Department of Space, Earth and Environment, Chalmers University of Technology, SE-412 96 G¨oteborg, Sweden c)Molde University College, P.O. Box 2110, N-6402 Molde, Norway Abstract In an exact quantum-mechanical framework we show that space-time expectation values of the second-quantized electromagnetic fields in the Coulomb gauge, in the presence of a classical source, automatically lead to causal and properly retarded elec- tromagnetic field strengths. The classical ~-independent and gauge invariant Maxwell's equations then naturally emerge and are therefore also consistent with the classical spe- cial theory of relativity. The fundamental difference between interference phenomena due to the linear nature of the classical Maxwell theory as considered in, e.g., classical optics, and interference effects of quantum states is clarified. In addition to these is- sues, the framework outlined also provides for a simple approach to invariance under time-reversal, some spontaneous photon emission and/or absorption processes as well as an approach to Vavilov-Cherenkovˇ radiation. The inherent and necessary quan- tum uncertainty, limiting a precise space-time knowledge of expectation values of the quantum fields considered, is, finally, recalled. arXiv:1801.09947v2 [quant-ph] 30 Mar 2019 1Corresponding author. Email address: [email protected] 2Email address: [email protected] 3Email address: [email protected] 1. Introduction The roles of causality and retardation in classical and quantum-mechanical versions of electrodynamics are issues that one encounters in various contexts (for recent discussions see, e.g., Refs.[1]-[14]). -

Time and Causality in General Relativity

Time and Causality in General Relativity Ettore Minguzzi Universit`aDegli Studi Di Firenze FQXi International Conference. Ponta Delgada, July 10, 2009 FQXi Conference 2009, Ponta Delgada Time and Causality in General Relativity 1/8 Light cone A tangent vector v 2 TM is timelike, lightlike, causal or spacelike if g(v; v) <; =; ≤; > 0 respectively. Time orientation and spacetime At every point there are two cones of timelike vectors. The Lorentzian manifold is time orientable if a continuous choice of one of the cones, termed future, can be made. If such a choice has been made the Lorentzian manifold is time oriented and is also called spacetime. Lorentzian manifolds and light cones Lorentzian manifolds A Lorentzian manifold is a Hausdorff manifold M, of dimension n ≥ 2, endowed with a Lorentzian metric, that is a section g of T ∗M ⊗ T ∗M with signature (−; +;:::; +). FQXi Conference 2009, Ponta Delgada Time and Causality in General Relativity 2/8 Time orientation and spacetime At every point there are two cones of timelike vectors. The Lorentzian manifold is time orientable if a continuous choice of one of the cones, termed future, can be made. If such a choice has been made the Lorentzian manifold is time oriented and is also called spacetime. Lorentzian manifolds and light cones Lorentzian manifolds A Lorentzian manifold is a Hausdorff manifold M, of dimension n ≥ 2, endowed with a Lorentzian metric, that is a section g of T ∗M ⊗ T ∗M with signature (−; +;:::; +). Light cone A tangent vector v 2 TM is timelike, lightlike, causal or spacelike if g(v; v) <; =; ≤; > 0 respectively. -

Pioneers in Optics: Christiaan Huygens

Downloaded from Microscopy Pioneers https://www.cambridge.org/core Pioneers in Optics: Christiaan Huygens Eric Clark From the website Molecular Expressions created by the late Michael Davidson and now maintained by Eric Clark, National Magnetic Field Laboratory, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32306 . IP address: [email protected] 170.106.33.22 Christiaan Huygens reliability and accuracy. The first watch using this principle (1629–1695) was finished in 1675, whereupon it was promptly presented , on Christiaan Huygens was a to his sponsor, King Louis XIV. 29 Sep 2021 at 16:11:10 brilliant Dutch mathematician, In 1681, Huygens returned to Holland where he began physicist, and astronomer who lived to construct optical lenses with extremely large focal lengths, during the seventeenth century, a which were eventually presented to the Royal Society of period sometimes referred to as the London, where they remain today. Continuing along this line Scientific Revolution. Huygens, a of work, Huygens perfected his skills in lens grinding and highly gifted theoretical and experi- subsequently invented the achromatic eyepiece that bears his , subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at mental scientist, is best known name and is still in widespread use today. for his work on the theories of Huygens left Holland in 1689, and ventured to London centrifugal force, the wave theory of where he became acquainted with Sir Isaac Newton and began light, and the pendulum clock. to study Newton’s theories on classical physics. Although it At an early age, Huygens began seems Huygens was duly impressed with Newton’s work, he work in advanced mathematics was still very skeptical about any theory that did not explain by attempting to disprove several theories established by gravitation by mechanical means. -

Causality in the Quantum World

VIEWPOINT Causality in the Quantum World A new model extends the definition of causality to quantum-mechanical systems. by Jacques Pienaar∗ athematical models for deducing cause-effect relationships from statistical data have been successful in diverse areas of science (see Ref. [1] and references therein). Such models can Mbe applied, for instance, to establish causal relationships between smoking and cancer or to analyze risks in con- struction projects. Can similar models be extended to the microscopic world governed by the laws of quantum me- chanics? Answering this question could lead to advances in quantum information and to a better understanding of the foundations of quantum mechanics. Developing quantum Figure 1: In statistics, causal models can be used to extract extensions of causal models, however, has proven challeng- cause-effect relationships from empirical data on a complex ing because of the peculiar features of quantum mechanics. system. Existing models, however, do not apply if at least one For instance, if two or more quantum systems are entangled, component of the system (Y) is quantum. Allen et al. have now it is hard to deduce whether statistical correlations between proposed a quantum extension of causal models. (APS/Alan them imply a cause-effect relationship. John-Mark Allen at Stonebraker) the University of Oxford, UK, and colleagues have now pro- posed a quantum causal model based on a generalization of an old principle known as Reichenbach’s common cause is a third variable that is a common cause of both. In the principle [2]. latter case, the correlation will disappear if probabilities are Historically, statisticians thought that all information conditioned to the common cause. -

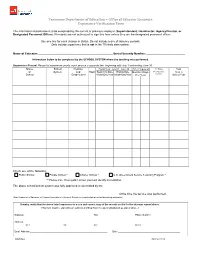

Experience Verification Form

Tennessee Department of Education – Office of Educator Licensure Experience Verification Form The information listed below is to be completed by the current or previous employer (Superintendent, Headmaster, Agency Director, or Designated Personnel Officer). Principals are not authorized to sign this form unless they are the designated personnel officer. Use one line for each change in status. Do not include leave of absence periods. Only include experience that is not in the TN state data system. Name of Educator: ________________________________________________ Social Security Number: _________________________ Information below to be completed by the SCHOOL SYSTEM where the teaching was performed. Experience Record: Please list experience yearly, each year on a separate line, beginning with July 1 and ending June 30. Name School Position Fiscal Year, July 01 - June 30 Time Employed % Time, Total of System and State Beginning Date Ending Date Months / Days Ex. Part-time, Days in Month/Day/Year Month/Day/Year Full-time School Year School Grade Level Per Year Check one of the following: Public School Private School * Charter School * U.S. Government Service Teaching Program * ** Please note: If non-public school you must identify accreditation. The above school/school system was fully approved or accredited by the ____________________________________________________________________ at the time the service was performed. (State Department of Education, or Regional Association of Colleges & Schools, or recognized private school accrediting -

Moral Relativism

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2020 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Carlo Alvaro CUNY New York City College of Technology How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/583 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Abstract This paper is a response to Park Seungbae’s article, “Defence of Cultural Relativism”. Some of the typical criticisms of moral relativism are the following: moral relativism is erroneously committed to the principle of tolerance, which is a universal principle; there are a number of objective moral rules; a moral relativist must admit that Hitler was right, which is absurd; a moral relativist must deny, in the face of evidence, that moral progress is possible; and, since every individual belongs to multiple cultures at once, the concept of moral relativism is vague. Park argues that such contentions do not affect moral relativism and that the moral relativist may respond that the value of tolerance, Hitler’s actions, and the concept of culture are themselves relative. In what follows, I show that Park’s adroit strategy is unsuccessful. Consequently, moral relativism is incoherent. Keywords: Moral relativism; moral absolutism; objectivity; tolerance; moral progress 2 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Moral relativism is a meta-ethical theory according to which moral values and duties are relative to a culture and do not exist independently of a culture. -

Philosophy of Chemistry: an Emerging Field with Implications for Chemistry Education

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 434 811 SE 062 822 AUTHOR Erduran, Sibel TITLE Philosophy of Chemistry: An Emerging Field with Implications for Chemistry Education. PUB DATE 1999-09-00 NOTE 10p.; Paper presented at the History, Philosophy and Science Teaching Conference (5th, Pavia, Italy, September, 1999). PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Chemistry; Educational Change; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; *Philosophy; Science Curriculum; *Science Education; *Science Education History; *Science History; Scientific Principles; Secondary Education; Teaching Methods ABSTRACT Traditional applications of history and philosophy of science in chemistry education have concentrated on the teaching and learning of "history of chemistry". This paper considers the recent emergence of "philosophy of chemistry" as a distinct field and explores the implications of philosophy of chemistry for chemistry education in the context of teaching and learning chemical models. This paper calls for preventing the mutually exclusive development of chemistry education and philosophy of chemistry, and argues that research in chemistry education should strive to learn from the mistakes that resulted when early developments in science education were made separate from advances in philosophy of science. Contains 54 references. (Author/WRM) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. ******************************************************************************** 1 PHILOSOPHY OF CHEMISTRY: AN EMERGING FIELD WITH IMPLICATIONS FOR CHEMISTRY EDUCATION PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS Office of Educational Research and improvement BEEN GRANTED BY RESOURCES INFORMATION SIBEL ERDURAN CENTER (ERIC) This document has been reproducedas ceived from the person or organization KING'S COLLEGE, UNIVERSITYOF LONDON originating it. -

A New Earth Study Guide.Pdf

A New Earth Study Guide Week 1 The consciousness that says ‘I am’ is not the consciousness that thinks. —Jean-Paul Sartre Affi rmation: "Through the guidance and wisdom of Spirit, I am being transformed by the renewing of my mind. All obstacles and emotions are stepping stones to the realization and appreciation of my sacred humanness." Study Questions – A New Earth (Review chapters 1 & 2, pp 1-58) Chapter 1: The Flowering of Human Consciousness Refl ect: Eckhart Tolle uses the image of the fi rst fl ower to begin his discussion of the transformation of consciousness. In your transformation, is this symbolism important to you? Describe. The two core insights of early religion are: 1) the normal state of human consciousness is dysfunctional (the Hindu call it maya – the veil of delusion) and 2) the opportunity for transformation is also in human consciousness (the Hindu call this enlightenment) (p. 8-9). What in your recent experience points to each of these insights? “To recognize one’s own insanity is, of course, the arising of sanity, the beginning of healing and transcendence” (p. 14). To what extent and in what circumstances (that you’re willing to discuss) does this statement apply to you? Religion is derived from the Latin word religare, meaning “to bind.” What, in your religious experience, have you been bound to? Stretching your imagination a bit, what could the word have pointed to in its original context? Spirit is derived from the Latin word spiritus, breath, and spirare, to blow. Aside from the allusion to hot air, how does this word pertain to your transformation? Do you consider yourself to be “spiritual” or “religious”? What examples of practices or beliefs can you give to illustrate? How does this passage from Revelation 21:1-4 relate to your transformation? Tease out as much of the symbolism as you can. -

Global History and the Present Time

Global History and the Present Time Wolf Schäfer There are three times: a present time of past things; a present time of present things; and a present time of future things. St. Augustine1 It makes sense to think that the present time is the container of past, present, and future things. Of course, the three branches of the present time are heavily inter- twined. Let me illustrate this with the following story. A few journalists, their minds wrapped around present things, report the clash of some politicians who are taking opposite sides in a struggle about future things. The politicians argue from histori- cal precedent, which was provided by historians. The historians have written about past things in a number of different ways. This gets out into the evening news and thus into the minds of people who are now beginning to discuss past, present, and future things. The people’s discussion returns as feedback to the journalists, politi- cians, and historians, which starts the next round and adds more twists to the en- tangled branches of the present time. I conclude that our (hi)story has no real exit doors into “the past” or “the future” but a great many mirror windows in each hu- man mind reflecting spectra of actual pasts and potential futures, all imagined in the present time. The complexity of the present (any given present) is such that no- body can hope to set the historical present straight for everybody. Yet this does not mean that a scientific exploration of history is impossible. History has a proven and robust scientific method.