Downloads/March2001.Pdf · Veal, A.J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mineral Profile

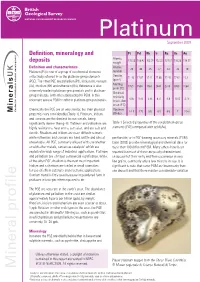

Platinum September 2009 Definition, mineralogy and Pt Pd Rh Ir Ru Os Au nt Atomic 195.08 106.42 102.91 192.22 101.07 190.23 196.97 deposits weight opme vel Atomic Definition and characteristics 78 46 45 77 44 76 79 de number l Platinum (Pt) is one of a group of six chemical elements ra UK collectively referred to as the platinum-group elements Density ne 21.45 12.02 12.41 22.65 12.45 22.61 19.3 (gcm-3) mi (PGE). The other PGE are palladium (Pd), iridium (Ir), osmium e Melting bl (Os), rhodium (Rh) and ruthenium (Ru). Reference is also 1769 1554 1960 2443 2310 3050 1064 na point (ºC) ai commonly made to platinum-group metals and to platinum- Electrical st group minerals, both often abbreviated to PGM. In this su resistivity r document we use PGM to refer to platinum-group minerals. 9.85 9.93 4.33 4.71 6.8 8.12 2.15 f o (micro-ohm re cm at 0º C) nt Chemically the PGE are all very similar, but their physical Hardness Ce Minerals 4-4.5 4.75 5.5 6.5 6.5 7 2.5-3 properties vary considerably (Table 1). Platinum, iridium (Mohs) and osmium are the densest known metals, being significantly denser than gold. Platinum and palladium are Table 1 Selected properties of the six platinum-group highly resistant to heat and to corrosion, and are soft and elements (PGE) compared with gold (Au). ductile. Rhodium and iridium are more difficult to work, while ruthenium and osmium are hard, brittle and almost pentlandite, or in PGE-bearing accessory minerals (PGM). -

Predictability of Pothole Characteristics and Their Spatial Distribution At

79_Chitiyo:Template Journal 12/15/08 11:16 AM Page 733 Predictability of pothole characteristics J o and their spatial distribution at u Rustenburg Platinum Mine r n by G. Chitiyo*, J. Schweitzer*, S. de Waal*, P. Lambert*, and a P. Olgilvie* l P a p Synopsis thermo-chemical erosion of the cumulus floor by new influxes of superheated magma best explains the observed data. e Prediction of pothole characteristics is a challenging task, Partial to complete melting of the cumulate floor occurred in r confronting production geologists at the platinum mines of three phases. The first represents the emplacement of hot the Bushveld Complex. The frequency, distribution, size, magma. This magma, due to turbulent flow and high chemical shape, severity and relationship (FDS3R) of potholes has a and physical potential, aggressively attacks the existing floor huge impact on mine planning and scheduling, and (crystal mush on the magma/floor interface). Regional consequently cost. It is with this in mind that this study was erosion is manifested by large, often coalescing potholes. initiated. During the second phase, when the magma emplacement Quantitative analysis of potholes indicates that pothole process ceased and cooling in situ started, two distinct size (area covered) can be described by two partly periods of pothole formation ensued. The first is related to overlapping lognormal distributions. These are referred to as rapid cooling along the relatively steep part of the Newton Populations A (smaller) and B (larger). The range of Cooling Curve, when Population B potholes nucleated observed pothole sizes conforms to a simple double randomly and grew rapidly with concurrent convective exponential growth model based on Newton’s Cooling Curve. -

Exkursionen Excursions

EXKURSIONEN EXCURSIONS 174 MITT.ÖSTERR.MINER.GES. 161 (2015) A GEOLOGICAL EXCURSION TO THE MINING AREAS OF SOUTH AFRICA by Aberra Mogessie, Christoph Hauzenberger, Sara Raic, Philip Schantl, Lukas Belohlavek, Antonio Ciriello, Donia Daghighi, Bernhard Fercher, Katja Goetschl, Hugo Graber, Magdalena Mandl, Veronika Preissegger, Gerald Raab, Felix Rauschenbusch, Theresa Sattler, Simon Schorn, Katica Simic, Michael Wedenig & Sebastian Wiesmair Institute of Earth Sciences, University of Graz, Universitaetsplatz 2, A-8010 Graz Frank Melcher, Walter Prochaska, Heinrich Mali, Heinz Binder, Marco Dietmayer-Kräutler, Franz Christian Friedman, Maximilian Mathias Haas, Ferdinand Jakob Hampl, Gustav Erwin Hanke, Wolfgang Hasenburger, Heidi Maria Kaltenböck, Peter Onuk, Andrea Roswitha Pamsl, Karin Pongratz, Thomas Schifko, Sebastian Emanuel Schilli, Sonja Schwabl, Cornelia Tauchner, Daniela Wallner & Juliane Hentschke Chair of Geology and Economic Geology, Mining University of Leoben, Peter-Tunner-Strasse 5, A-8700 Leoben Christoph Gauert Department of Geology, University of the Free State, South Africa 1. Preface Almost a year ago Aberra Mogessie planned to organize a field excursion for the students of the Institute of Earth Sciences, University of Graz. The choices were Argentina, Ethiopia (where we had organized past excursions) and South Africa. Having discussed the matter with Christoph Hauzenberger concerning geology, logistics etc. we decided to organize a field excursion to the geologically interesting mining areas of South Africa. We contacted Christoph Gauert from the University of Free State, South Africa to help us with the local organization especially to get permission from the different mining companies to visit their mining sites. We had a chance to discuss with him personally during his visit to our institute at the University of Graz in May 2014 and make the first plan. -

ECONOMIC GEOLOGY RESEARCH INSTITUTE HUGH ALLSOPP LABORATORY University of the Witwatersrand Johannesburg

ECONOMIC GEOLOGY RESEARCH INSTITUTE HUGH ALLSOPP LABORATORY University of the Witwatersrand Johannesburg CHROMITITES OF THE BUSHVELD COMPLEX- PROCESS OF FORMATION AND PGE ENRICHMENT J.A. KINNAIRD, F.J. KRUGER, P.A.M. NEX and R.G. CAWTHORN INFORMATION CIRCULAR No. 369 UNIVERSITY OF THE WITWATERSRAND JOHANNESBURG CHROMITITES OF THE BUSHVELD COMPLEX – PROCESSES OF FORMATION AND PGE ENRICHMENT by J. A. KINNAIRD, F. J. KRUGER, P.A. M. NEX AND R.G. CAWTHORN (Department of Geology, School of Geosciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Private Bag 3, P.O. WITS 2050, Johannesburg, South Africa) ECONOMIC GEOLOGY RESEARCH INSTITUTE INFORMATION CIRCULAR No. 369 December, 2002 CHROMITITES OF THE BUSHVELD COMPLEX – PROCESSES OF FORMATION AND PGE ENRICHMENT ABSTRACT The mafic layered suite of the 2.05 Ga old Bushveld Complex hosts a number of substantial PGE-bearing chromitite layers, including the UG2, within the Critical Zone, together with thin chromitite stringers of the platinum-bearing Merensky Reef. Until 1982, only the Merensky Reef was mined for platinum although it has long been known that chromitites also host platinum group minerals. Three groups of chromitites occur: a Lower Group of up to seven major layers hosted in feldspathic pyroxenite; a Middle Group with four layers hosted by feldspathic pyroxenite or norite; and an Upper Group usually of two chromitite packages, hosted in pyroxenite, norite or anorthosite. There is a systematic chemical variation from bottom to top chromitite layers, in terms of Cr : Fe ratios and the abundance and proportion of PGE’s. Although all the chromitites are enriched in PGE’s relative to the host rocks, the Upper Group 2 layer (UG2) shows the highest concentration. -

The Centenary of the Discovery of Platinum in the Bushveld Complex (10Th November, 1906)

CAWTHORN, R.G. The centenary of the discovery of platinum in the Bushveld Complex (10th November, 1906). International Platinum Conference ‘Platinum Surges Ahead’, The Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, 2006. The centenary of the discovery of platinum in the Bushveld Complex (10th November, 1906) R.G. CAWTHORN School of Geosciences, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa The earliest authenticated scientific report of the occurrence of platinum in rocks from the Bushveld Complex appears to be by William Bettel on 10th November 1906. Thereafter, prospecting of the chromite-rich rocks for platinum proved frustrating. I suggest that the resurgence of interest shown by Dr Hans Merensky in 1924 resulted from his realization that newly-panned platinum had a different grain size from that in the chromite layers and indicated a different source rock, which he located and it became known as the Merensky Reef. Merensky’s discoveries in Johannesburg). He found it contained ‘silver, gold, The story of Dr. Hans Merensky’s discoveries of the platinum and iridium (with osmium)’. Hence, the presence platinum-rich pipes and the Merensky Reef itself in 1924 of the platinum-group elements (PGE) in South Africa in have been well documented (Cawthorn, 1999; Scoon and minor amounts was well-established by the end of the Mitchell, 2004, and references therein), but the events that nineteenth century. preceded it have not been summarized. In the probable centenary year of the first report of platinum in the In situ platinum Bushveld it is appropriate to review the events between In his article Bettel reported that he had ‘recently’ (i.e. -

Pdf 358.5 Kb

Seventy-fifth Anniversary of the Discovery of the Platiniferous MerenskvJ Reef THE LARGEST PLATINUM DEPOSITS IN THE WORLD By Professor R. Grant Cawthorn Department of Geology, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa The Merensky Reef is a thin layer of igneous rock in the Bushveld Complex in South Africa, which, with an underlying layer, the Upper Group 2 chromitite, contains 75 per cent of the world’s known platinum resources. It was discovered in September 1924 by Hans Merensky, and by early 1926 had been traced for about 150 km. However, large-scale mining of the reef did not develop until aproliferation of uses for theplatinumgroup metals in the 1950s increased demand and price. Successful extraction of metal from the Upper Group 2 chromitite had to wait until the 1970s for metallurgical developments. In 1923 platinum was discovered in the rivers. In early June 1924, a white metal was Waterberg region of South Africa, and alerted panned in a stream on a small farm called geologists to its presence there, see Figure 1. At Maandagshoek, 20 km west of Burgersfort, see that time world demand for platinum was not Figure 2, by a farmedprospector called Andries great, and the economic slump during the years Lombaard. Suspecting it was platinum, he of the Great Depression, which followed soon sent it to Dr Hans Merensky for confirmation. afterwards, reduced demand and price still fur- Hans Merensky was a consulting geologist and ther. Consequently, the discovery in 1924 was mining engineer in Johannesburg. Together, almost before its time. Lombaard and Merensky followed the “tail” of Platinum, like gold and diamonds, has a high platinum in their pan upstream into some hills density and forms stable minerals, which accu- on Maandagshoek, where they finally found mulate at the sandy bottoms of streams and platinum in solid rock on 15th August 1924. -

The Bushveld Igneous Complex

The Bushveld Igneous Complex THE GEOLOGY OF SOUTH AFRICA’S PLATINUM RESOURCES By C. A. Cousins, MSC. Johannesburg Consolidated Investment Company Limited A vast composite body of plutonic and volcanic rock in the central part of the Transvaal, the Bushveld igneous complex includes the platinum reef worked by Rustenburg Platinum Mines Limited and constituting the world’s greatest reserve of the platinum metals. This article describes the geological and economic aspects of this unusually interesting formation. In South Africa platinum occurs chiefly in square miles. Two of these areas lie at the the Merensky Reef, which itself forms part of eastern and western ends of the Bushveld and the Bushveld igneous complex, an irregular form wide curved belts, trending parallel to oval area of some 15,000 square miles occupy- the sedimentary rocks which they overlie, and ing a roughly central position in the province dipping inwards towards the centre of the of the Transvaal. A geological map of the Bushveld at similar angles. The western belt area, which provides the largest known has a flat sheet-like extension reaching the example of this interesting type of formation, western boundary of the Transvaal. The is shown on the facing page. third area extends northwards and cuts out- The complex rests upon a floor of sedi- side the sedimentary basin. Its exact relation- mentary rocks of the Transvaal System. This ship to the other outcrops within the basin floor is structurally in the form of an immense has not as yet been solved. oval basin, three hundred miles long and a As the eastern and western belts contain hundred miles broad. -

Key Trends in the Resource Sustainability of Platinum Group Elements

Ore Geology Reviews 46 (2012) 106–117 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Ore Geology Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/oregeorev Key trends in the resource sustainability of platinum group elements Gavin M. Mudd ⁎ Environmental Engineering, Department of Civil Engineering, Monash University, Clayton, 3800, Melbourne, Australia article info abstract Article history: Platinum group elements (PGEs) are increasingly used in a variety of environmentally-related technologies, Received 6 November 2011 such as chemical process catalysts, catalytic converters for vehicle exhaust control, hydrogen fuel cells, Received in revised form 3 February 2012 electronic components, and a variety of specialty medical uses, amongst others — almost all of which have Accepted 3 February 2012 strong expected growth to meet environmental and technological challenges this century. Economic Available online 11 February 2012 geologists have been arguing on the case of abundant geologic resources of PGEs for some time while others still raise concerns about long-term supply — yet there remains no detailed analysis of formally reported Keywords: Platinum group elements (PGEs) mineral resources and key trends in the PGEs sector. This paper presents such a detailed review of the Economic mineral resources PGEs sector, including detailed mine production statistics and mineral resources by principal ore types, pro- Mineral resource sustainability viding an authoritative case study on the resource sustainability for a group of elements which are uniquely Bushveld Complex concentrated in a select few regions of the earth. The methodology, compiled data sets and trends provide Great Dyke strong assurance on the contribution that PGEs can make to the key sustainability and technology challenges – Noril'sk Talnakh of the 21st century such as energy and pollution control. -

Early Fracturing and Impact Residue Emplacement: Can Modelling Help to Predict Their Location in Major Craters?

Early fracturing and impact residue emplacement: Can modelling help to predict their location in major craters? Item Type Proceedings; text Authors Kearsley, A.; Graham, G.; McDonnell, T.; Bland, P.; Hough, R.; Helps, P. Citation Kearsley, A., Graham, G., McDonnell, T., Bland, P., Hough, R., & Helps, P. (2004). Early fracturing and impact residue emplacement: Can modelling help to predict their location in major craters?. Meteoritics & Planetary Science, 39(2), 247-265. DOI 10.1111/j.1945-5100.2004.tb00339.x Publisher The Meteoritical Society Journal Meteoritics & Planetary Science Rights Copyright © The Meteoritical Society Download date 23/09/2021 21:19:20 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Version Final published version Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/655802 Meteoritics & Planetary Science 39, Nr 2, 247–265 (2004) Abstract available online at http://meteoritics.org Early fracturing and impact residue emplacement: Can modelling help to predict their location in major craters? Anton KEARSLEY,1* Giles GRAHAM,2 Tony McDONNELL,3 Phil BLAND,4 Rob HOUGH,5 and Paul HELPS6 1Department of Mineralogy, The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK 2Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, California, USA 3Planetary and Space Sciences Research Institute, The Open University, Milton Keynes, MK7 6AA, UK 4Department of Earth Science and Engineering, Imperial College London, London SW7 2AZ, UK 5Museum of Western Australia, Francis Street, Perth, Western Australia 6000, Australia 6School of Earth Sciences and Geography, Kingston University, Kingston-upon-Thames, Surrey, KT1 2EE, UK *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] (Received 30 June 2003; revision accepted 15 December 2003) Abstract–Understanding the nature and composition of larger extraterrestrial bodies that may collide with the Earth is important. -

Sgs Qualifor Forest Management Certification Report

SGS QUALIFOR Doc. Number: AD 36A-12 (Associated Documents) Doc. Version date: 21 Sept. 2010 Page: 1 of 50 Approved by: Gerrit Marais FOREST MANAGEMENT CERTIFICATION REPORT SECTION A: PUBLIC SUMMARY Project Nr: 7599-ZA Client: HM Timber Limited – Berg and East Griqualand Forests Web Page: www.hansmerensky.co.za Address: PO Box 20, Weza, KwaZulu-Natal, 4685 Country: South Africa Certificate Nr. SGS-FM/COC-000780 Certificate Type: Forest Management / CoC Date of Issue 29 July 2008 Date of expiry: 28 July 2013 SGS Forest Management Standard (AD33) adapted for South Africa, version 04, of 29 March Evaluation Standard 2010 Forest Zone: Temperate Total Certified Area 56,044.64ha Scope: The forest management of Singisi’s hardwood and softwood plantations in the KZN & E Cape provinces of South Africa for the production of FSC Pure timber for sale to clients or supply to Singisi and Weza sawmills for the production of Sawn Timber and sawmill by-products for sale on the Chain of Custody Transfer system Location of the FMUs The FMU’s are located in the Southern Kwa-Zulu/Natal province of South Africa near the included in the scope towns of Harding and Howick. Company Contact Hamish Whyle Person: Address: PO Box 20 Weza 4685 Tel: 039 553 0401 Fax 039 553 0425 Email: [email protected] Evaluation dates: SGS South Africa (Qualifor Programme) 58 Melville Road, BooysensBooysens--PO PO Box 82582, Southdale 21852185-- South Africa Systems and Services Certification Division Contact Programme Director at t. +27 11 681-2500- [email protected] www.agriculture-food.sgs.com/en/Forestry / AD 36A-12 Page 2 of 50 Main Evaluation 27 – 30 / 5/ 2008 Surveillance 1 4 – 6 May 2009 Surveillance 2 19 – 21 April 2010 Surveillance 3 24 – 26 May 2011 & COF 11 August 2011 Surveillance 4 Copyright: © 2011 SGS South Africa (Pty) Ltd All rights reserved AD 36A-12 Page 3 of 50 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. -

South African Research on Volcanic and Related Rocks and Mantle-Derived Materials: 2003-2006

South African Research on volcanic and related rocks and mantle-derived materials: 2003-2006 J.S. Marsh South African National Correspondent, IAVCEI Department of Geology Rhodes University Grahamstown 6140 South Africa South Africa has no formal organizational or research structures dedicated to the principle aims of International Association of Volcanology and Chemistry of Earth’s Interior (IAVCEI) and over the period of the review there were no national research programmes which advance the main thrusts of IAVCEI. The association has a system of personal membership and the number of IAVCEI members in South Africa has not generally exceeded half a dozen over the period under review, although the potential membership is much greater as there are many scientists carrying out research on volcanic and intrusive rocks as well as mantle materials. These researchers are largely based at universities, the Council for Geoscience, as well as some mining and exploration companies, particularly those with interests in mineralization associated with the Bushveld Complex as well as diamondiferous kimberlite. Over the period of review the research of small informal groups and individuals has produced a substantial number of papers in igneous rocks and mantle materials. These outputs can be conveniently grouped as follows. Archaean Greenstones and Granitoids and Proterozoic Igneous suites. There is a steady output of research in these areas particularly in Archaean suites with interest in both the ultramafic-mafic komatiitic rocks as well as granitoids. Of note is the description of a new class of komatiite characterized by high silica and ultra depletion in incompatible elements. Bushveld Complex The Bushveld Complex one of the world’s largest layered igneous complexes is host to giant ore deposits of Cr, PGE, and V. -

Thermal and Chemical Characteristics of Hot Water Springs in the Northern Part of the Limpopo Province, South Africa

Thermal and chemical characteristics of hot water springs in the northern part of the Limpopo Province, South Africa J Olivier1*, JS Venter2 and CZ Jonker1 1Department of Environmental Sciences, UNISA, Private Bag X6, Florida 1710, South Africa 2Council for Geoscience, Private Bag X112, Pretoria 0001, South Africa Abstract In many countries thermal springs are utilised for a variety of purposes, such as the generation of power, direct space heating, industrial processes, aquaculture and many more. The optimal use of a thermal spring is largely dependent upon its physical and chemical characteristics. This article focuses on the thermal and chemical features of 8 thermal springs located in the northern part of the Limpopo Province, South Africa. Field data and water samples were collected from Evangelina, Tshipise, Sagole, Môreson, Siloam, Mphephu, Minwamadi and Die Eiland for analysis of physical and chemical parameters. The temperatures at source vary from 30°C to 67.5°C. The springs are associated with faults and impermeable dykes and are assumed to be of meteoric origin. The mineral composition of the thermal waters reflects the geological formations found at the depth of origin. None of the spring waters are fit for human consumption since they contain unacceptably high levels of bromide ions. Six springs do not conform to domestic water quality guidelines with respect to fluoride levels. Unacceptably high values of mercury were detected at Môreson and Die Eiland. Spring water at Evangelina is contaminated with selenium and arsenic. It is important to keep such limitations in mind when determin- ing the ultimate use of the thermal springs.