The Role of Elevated Views

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic Map of Commuter Rail, Interurbans, and Rapid

l'Assomption Montreal Area Historical Map of Interurban, Commuter Rail and Rapid Transit Legend Abandoned Interurban Line St-Lin Abandoned Line This map aims to show the extensive network of interurban,* commuter rail, On-Street (Frequent Stops) (Expo Express) Abandoned Rail Line Acitve Line and rapid transit lines operated in the greater Montreal Region. The city has St-Paul-l'Ermite (Metro) Active Rail Line Abandoned Station seen a dramatic changes in the last fifty years in the evolution of rail transit. La Ronde (Expo Express) La Plaine Streetcars and Interurbans have come and gone, and commuter rail was Viger Abandoned Station Active Stations Bruchesi Du College Abandoned dwindled down to two lines and is now up to three. Over these years the Metro Charlemange / Repentigny Temporary Station Parc Blue Line Longueuil Le Page Chambly was built as was the now dismantled Expo Express. Abandoned Interurban Stop Yellow Line Square-Victoria Orange Line Granby Abandoned Interurban Station Ravins Then Abandoned Rail Station McGill Green Line -Eric Peissel, Author Pointe-aux-Trembles Pointe Claire Active Station A special thanks to all who helped compile this map: [Lakeside] [with Former Name] Blainville Snowdon Interchange Station Tom Box, Hugh Brodie, Gerry Burridge, Marc Dufour, Louis Desjardins, James Hay, Mont-Royal Active Station Paul Hogan, C.S. Leschorn, & Pat Scrimgeor Pointe-aux- Trembles Sainte-Therese Riviere-des-Prairies Sources: Leduc, Michael Montreal Island Railway Stations - CNR Rosemere Ste-Rosalie-Jct. Sainte-Rose St-Hyacinthe Leduc, Michael Montreal Island Railway Stations - CPR Lacordaire Montreal-North * Tetreauville Grenville Some Authors have classified the Montreal Park and Island and Montreal Terminal Railway as Interurbans but most authoritive books on Interurbans define Ste. -

Ucrs-258-1967-Jul-Mp-897.Pdf

CANADIAN PACIFIC MOTIVE POWER NOTES CP BUSINESS CAR GETS A NEW NAME * To facilitate repairs to its damaged CLC cab * A new name appeared in the ranks of Canadian unit 4054, CP recently purchased the carbody Pacific business cars during May, 1967. It is of retired CN unit 9344, a locomotive that was "Shaughnessy", a name recently applied to the removed from CN records on February 15th, 1966. former car "Thorold", currently assigned to the Apparently the innards of 4054 are to be in• Freight Traffic Manager at Vancouver. It hon• stalled in the carbody of 9344 and the result• ours Thomas G. Shaughnessy, later Baron Shaugh• ant unit will assume the identity of CP 4054. nessy, G.C.VoO., who was Canadian Pacific's The work will be done at CP's Ogden Shops in third president (1899-1909), first chairman and Calgary. president (1910-1918) and second chairman (1918-1923). The car had once been used by Sir Edward W. Beatty, G.B.E., the Company's fourth president, and was named after his * Canadian Pacific returned all of its leased birthplace, Thorold, Ontario. Boston & Maine units to the B&M at the end of May. The newly-named "Shaughnessy" joins three oth• er CP business cars already carrying names of individuals now legendary in the history of the Company —"Strathcona", "Mount Stephen" and "Van Horne". /OSAL BELOW: Minus handrails and looking somewhat the worse for wear, CP's SD-40 5519 was photographed at Alyth shops on June 10th, after an affair with a mud slide. /Doug Wingfield The first unit of a fleet of 150 cabooses to bo put in CN service this simmer has been making a get-acquainted tour of the road's eastern lines. -

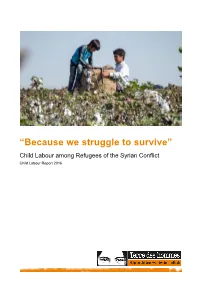

'Because We Struggle to Survive'

“Because we struggle to survive” Child Labour among Refugees of the Syrian Conflict Child Labour Report 2016 Disclaimer terre des hommes Siège | Hauptsitz | Sede | Headquarters Avenue de Montchoisi 15, CH-1006 Lausanne T +41 58 611 06 66, F +41 58 611 06 77 E-mail : [email protected], CCP : 10-11504-8 Research support: Ornella Barros, Dr. Beate Scherrer, Angela Großmann Authors: Barbara Küppers, Antje Ruhmann Photos : Front cover, S. 13, 37: Servet Dilber S. 3, 8, 12, 21, 22, 24, 27, 47: Ollivier Girard S. 3: Terre des Hommes International Federation S. 3: Christel Kovermann S. 5, 15: Terre des Hommes Netherlands S. 7: Helmut Steinkeller S. 10, 30, 38, 40: Kerem Yucel S. 33: Terre des hommes Italy The study at hand is part of a series published by terre des hommes Germany annually on 12 June, the World Day against Child Labour. We would like to thank terre des hommes Germany for their excellent work, as well as Terre des hommes Italy and Terre des Hommes Netherlands for their contributions to the study. We would also like to thank our employees, especially in the Middle East and in Europe for their contributions to the study itself, as well as to the work of editing and translating it. Terre des hommes (Lausanne) is a member of the Terre des Hommes International Federation (TDHIF) that brings together partner organisations in Switzerland and in other countries. TDHIF repesents its members at an international and European level. First published by terre des hommes Germany in English and German, June 2016. -

LOYALTY in the WORKS of SAINT-EXUPBRY a Thesis

LOYALTY IN THE WORKS OF SAINT-EXUPBRY ,,"!"' A Thesis Presented to The Department of Foreign Languages The Kansas State Teachers College of Emporia In Partial Fulfillment or the Requirements for the Degree Mastar of Science by "., ......, ~:'4.J..ry ~pp ~·.ay 1967 T 1, f" . '1~ '/ Approved for the Major Department -c Approved for the Graduate Council ~cJ,~/ 255060 \0 ACKNOWLEDGMENT The writer wishes to extend her sincere appreciation to Dr. Minnie M. Miller, head of the foreign language department at the Kansas State Teachers College of Emporia, for her valuable assistance during the writing of this thesis. Special thanks also go to Dr. David E. Travis, of the foreign language department, who read the thesis and offered suggestions. M. E. "Q--=.'Hi" '''"'R ? ..... .-.l.... ....... v~ One of Antoine de Saint-Exupe~J's outstanding qualities was loyalty. Born of a deep sense of responsi bility for his fellowmen and a need for spiritual fellow ship with them it became a motivating force in his life. Most of the acts he is remeffibered for are acts of fidelityo Fis writings too radiate this quality. In deep devotion fo~ a cause or a friend his heroes are spurred on to unusual acts of valor and sacrifice. Saint-Exupery's works also reveal the deep movements of a fervent soul. He believed that to develop spiritually man mQst take a stand and act upon his convictions in the f~c0 of adversity. In his boo~ UnSens ~ la Vie, l he wrote: ~e comprenez-vous Das a~e le don de sol, le risque, ... -

Editor James A. Brown Contributors to This Issue: John Bromley, Reg

UCRS NEWSLETTER - 1967 ─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── July, 1967 - Number 258 details. Published monthly by the Upper Canada Railway August 17th; (Thursday) - CBC re-telecast of Society, Incorporated, Box 122, Terminal A, “The Canadian Menu” in which “Nova Toronto, Ontario. Scotia” plays a part. (April NL, page Editor James A. Brown 49) 9:00 p.m. EDT. Authorized as Second Class Matter by August 18th; (Friday) - Summer social evening the Post Office Department, Ottawa, Ontario, at 587 Mt. Pleasant Road, at which and for payment of postage in cash. professional 16 mm. films will be shown Members are asked to give the Society and refreshments served. Ladies are at least five weeks notice of address changes. welcome. 8:00 p.m. Please address NEWSLETTER September 15th; (Friday) - Regular meeting, contributions to the Editor at 3 Bromley at which J. A. Nanders, will discuss Crescent, Bramalea, Ontario. No a recent European trip, with emphasis responsibility is assumed for loss or on rail facilities in Portugal. non-return of material. COMING THIS FALL! The ever-popular All other Society business, including railroadianna auction, two Steam membership inquiries, should be addressed to trips on the weekend of September 30th, UCRS, Box 122, Terminal A, Toronto, Ontario. and the annual UCRS banquet. Details Cover Photo: This month’s cover -- in colour soon. to commemorate the NEWSLETTER’s Centennial READERS’ EXCHANGE Issue -- depicts Canada’s Confederation Train CANADIAN TIMETABLES WANTED to buy or trade. winding through Campbellville, Ontario, on What have you in the way of pre-1950 public the Canadian Pacific. The date: June 7th, or employee’s timetables from any Canadian 1967. -

Notions of Self and Nation in French Author

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 6-27-2016 Notions of Self and Nation in French Author- Aviators of World War II: From Myth to Ambivalence Christopher Kean University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Kean, Christopher, "Notions of Self and Nation in French Author-Aviators of World War II: From Myth to Ambivalence" (2016). Doctoral Dissertations. 1161. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1161 Notions of Self and Nation in French Author-Aviators of World War II: From Myth to Ambivalence Christopher Steven Kean, PhD University of Connecticut, 2016 The traditional image of wartime aviators in French culture is an idealized, mythical notion that is inextricably linked with an equally idealized and mythical notion of nationhood. The literary works of three French author-aviators from World War II – Antoine de Saint- Exupéry, Jules Roy, and Romain Gary – reveal an image of the aviator and the writer that operates in a zone between reality and imagination. The purpose of this study is to delineate the elements that make up what I propose is a more complex and even ambivalent image of both individual and nation. Through these three works – Pilote de guerre (Flight to Arras), La Vallée heureuse (The Happy Valley), and La Promesse de l’aube (Promise at Dawn) – this dissertation proposes to uncover not only the figures of individual narratives, but also the figures of “a certain idea of France” during a critical period of that country’s history. -

Ar.Itorne DE Sarrvr- Exupf Nv

Ar.itorNE DE Sarrvr-Exupf nv Born: Lyon, France June 29, 1900 Died: Near Corsica July3l ,7944 Throughhis autobiographicalworhs, Saint-Exupery captures therra of earlyaviation uith his$rical prose and ruminations, oftenrnealing deepertruths about the human condition and humanity'ssearch for meaningand fulfillrnar,t. teur" (the aviator), which appeared in the maga- zine LeNauired'Argentin 1926.Thus began many of National Archive s Saint-Exup6ry's writings on flying-a merging of two of his greatestpassions in life. At the time, avia- Brocnaprrv tion was relatively new and still very dangerous. Antoine Jean-Baptiste Marie Roger de Saint- The technology was basic, and many pilots relied Exup6ry (sahn-tayg-zew-pay-REE)rvas born on on intuition. Saint-Exup6ry,however, was drawn to June 29, 1900, in Lyon, France, the third of five the adventure and beauty of flight, which he de- children in an aristocratic family. His father died of picted in many of his works. a stroke lvhen Saint-Exup6ry was only three, and Saint-Exup6rybecame a frontiersman of the sky. his mother moved the family to Le Mans. Saint- He reveled in flying open-cockpit planes and loved Exup6ry, knor,vn as Saint-Ex, led a happy child- the freedom and solitude of being in the air. For hood. He wassurrounded by many relativesand of- three years,he r,vorkedas a pilot for A6ropostale, a ten spent his summer vacations rvith his family at French commercial airline that flew mail. He trav- their chateau in Saint-Maurice-de-Remens. eled berween Toulouse and Dakar, helping to es- Saint-Exup6ry went to Jesuit schools and to a tablish air routes acrossthe African desert. -

Composantes D'aménagement

5 COMPOSANTES D’AMÉNAGEMENT 5.1 Les trois gestes d’aménagement se COMPOSANTES concrétisent par des propositions qui s’appliquent aux quatre grandes composantes PAYSAGÈRES structurantes du Parc : les bâtiments, les œuvres d’art et les ouvrages d’art, le réseau de circulation et les surfaces minéralisées, les habitats végétaux et les milieux hydriques. COMPOSANTES PAYSAGÈRES Pour chacune de ces quatre composantes, un inventaire est dressé BÂTIMENTS, ŒUVRES D’ART ET OUVRAGES D’ART RÉSEAU DE CIRCULATION ET SURFACES MINÉRALISÉES afin d’en comprendre la situation actuelle. L’analyse des intérêts et des problèmes ont permis de formuler des intentions d’aménagement qui se traduisent dans les plans et dans les diverses illustrations des propositions. HABITATS VÉGÉTAUX MILIEUX HYDRIQUES chap.5_ 248 PLAN DIRECTEUR DE CONSERVATION, D’AMÉNAGEMENT ET DE DÉVELOPPEMENT DU PARC JEAN-DRAPEAU 2020-2030 LES BÂTIMENTS, LES ŒUVRES D’ART ET LES OUVRAGES D’ART LA LIAISON DES CŒURS DES LA PROMENADE RIVERAINE LES ATTACHES ENTRE LES DEUX ÎLES RIVES ET LES CŒURS Mise en valeur, grâce à des travaux de Ponctuation de la promenade riveraine par Implantation de structures ponctuelles de restauration et de réhabilitation, du riche l’implantation de pavillons de services ainsi liaison sous forme de passerelles et de quais patrimoine bâti et de la collection d’œuvres que par la réhabilitation de la passerelle du offrant de nouvelles expériences nourries par d’art public Cosmos et du pont de l’Expo-Express les innovations inspirantes de l’Expo 67 CHAPITRE 5. COMPOSANTES D’AMÉNAGEMENT chap.5_ 249 LES BÂTIMENTS, LES ŒUVRES D’ART ET LES OUVRAGES D’ART INVENTAIRE N Vieux-Montréal L’inventaire des bâtiments, des œuvres d’art et des ouvrages d’art permet de rendre compte de l’important corpus bâti du Parc. -

Ucrs Newsletter - 1967 ───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

UCRS NEWSLETTER - 1967 ─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── August, 1967 - Number 259 Toronto, Ontario. 8:00 p.m. Published monthly by the Upper Canada Railway September 15th; (Friday) - Regular meeting, Society, Incorporated, Box 122, Terminal A, at which J. A. Nanders, will discuss Toronto, Ontario. a recent European trip, with emphasis Editor James A. Brown on rail facilities in Portugal. Authorized as Second Class Matter by September 30th; (Saturday) - STEAM/Diesel the Post Office Department, Ottawa, Ontario, excursion to Lindsay and Haliburton. and for payment of postage in cash. October 1st; (Sunday) - STEAM excursion to Fort Members are asked to give the Society Erie. Full details on both at least five weeks notice of address changes. excursions may be obtained from UCRS Please address NEWSLETTER at Box 122, Terminal A, Toronto. contributions to the Editor at 3 Bromley NOTICE re “Centennial Steam Tour”: Crescent, Bramalea, Ontario. No Termination of operating arrangements between responsibility is assumed for loss or Rail Tours, Incorporated, and the Maryland non-return of material. & Pennsylvania Railroad has necessitated the All other Society business, including cancellation of the bus tour of Pennsylvania membership inquiries, should be addressed to and New York, originally scheduled for October UCRS, Box 122, Terminal A, Toronto, Ontario. 6th to 9th. Cover Photo: The scene is one of congestion November 17th; (Friday) - Sort out your surplus at Front and Bathurst on June 22nd, 1931, as railroadiana now for the UCRS Auction, the FLEET route is inaugurated over the which will be presided over this year newly-rebuilt Bathurst Street bridge. Less by Mr. Omer Lavallee, of Montreal. than a month later, the route name would be READERS’ EXCHANGE changed to the familiar FORT. -

Terre Des Hommes – Annual Report 2017

Annual Report 2017 2 terre des hommes – Annual Report 2017 Imprint Contents terre des hommes 3 Greeting Help for Children in Need 4 Report by the Executive Board 6 terre des hommes’ vision Head Office 8 terre des hommes’ programme activities Ruppenkampstraße 11a 49 084 Osnabrück Germany Goals and impacts of our programme activity 10 Participation makes children strong Phone +49 (0) 5 41/71 01-0 13 Creating safe spaces for children Telefax +49 (0) 5 41/70 72 33 16 Children’s right to a healthy environment [email protected] 19 Advocacy for children’s rights www.tdh.de 22 Map of project countries Account of donations BIC NOLADE 22 XXX 28 Quality assurance, monitoring, transparency IBAN DE34 2655 0105 0000 0111 22 30 Risk management 31 The International Federation TDHIF Editorial Staff 32 You change more than you give Wolf-Christian Ramm (editor in charge), 36 The 2017 donation year Tina Böcker-Eden, Michael Heuer, 38 »How far would you go?!« Athanasios Melissis, Iris Stolz 40 terre des hommes spotlights itself Editorial Assistant Cornelia Dernbach Balance 2017 44 terre des hommes in figures Photos Front cover: M. Pelser; p. 3 top, 8, 37: F. Kopp; p. 3 bottom, 50 Outlook and future challenges 14, 19, 27, 33 bottom, 40 top, 52 bottom, 52 m., 53 top: 52 Organisation structure of terre des hommes C. Kovermann / terre des hommes; p. 4: M. Klimek; 54 Organisation chart of terre des hommes p. 7: S. Basu / terre des hommes; p. 11, 21: Kindernothilfe; p. 12: T. Schwab; p. 13: terre des hommes Lausanne; p. -

Communicating for Terre Des Hommes on Social Networks. Impressum

Social Media Toolkit. Communicating for Terre des hommes on social networks. Impressum. Responsible for publication : Yann Graf Production Coodinator : Laure Silacci Translations Coordinator : Lucie Concordel English Translation : Probst German Translation : Anina Kurth Layout : Angélique Bühlmann This guide was edited in 2012 by the communication department of Terre des hommes. It is based on the Social Media Toolkit of the American Red Cross. Please do not hesitate to share your comments with us to help us improve the guide in the future ([email protected]). We would like to sincerely thank Christine Brosteaux, Mylène Ntamatungiro, Joseph Aguetant and Antoine Lissorgues for their help in producing this document. © Tdh / April 2015 – Version 1.1 Summary 1. Introduction 4 2. Section 1 - Definition 5 2.a Understanding social media 5 2.b Managing the risks 7 2.c The reputation of Tdh : Being cautious online 8 2.d The main platforms 9 2.e Before you begin 10 3. Section 2 - Practical guide 13 3.a Getting started on Facebook 13 3.b Getting started on Twitter 18 4. Appendices 23 Social Media Toolkit 3 1. Introduction. With a billion users on Facebook and Twitter, social networks have become indispensable. Internet users spend more time on these platforms than on any other site. Today, social networks are used by numerous NGOs to spread their ideas to a larger public and to combat apathy. They enable the beneficiaries, employees and partners of Terre des hommes ( Tdh ) to have a voice. Utilised in the right way, they will help promote the work done by Tdh by informing the public about the situation of children around the world and permitting the public to present new concerns. -

UPPER CANADA RAILWAY SOCIETY 2 • UCRS Newsletter • March 1991

50th ANNIVERSARY 1 941 -1 991 NUMBER 497 MARCH 1991 UPPER CANADA RAILWAY SOCIETY 2 • UCRS Newsletter • March 1991 UPPER CANADA RAILWAY SOCIFTY EDITOR IN THIS MONTH'S NEWSLETTER Pat Scrimgeour Calgary Tests Three-Phase AC Tradion ... 3 Rapid Transit In Canada — 1 4 CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Toronto's Gloucester Subway Cars 8 ^Tiecu^iettenrJohn Carter, Art Clowes, Scott Hask To the Lands of the Geniuses — 14 ... 10 Don McQueen, Sean Robitaille, The Ferrophiliac Column 12 Number 497 - March 1991 Gray Scrimgeour, Chris Spinney, Some Telegraph History 14 John Thompson, Gord Webster Book Reviews 14 UPPER CANADA RAILWAY SOCIEPr' Transcontinental — Railway News 1.5 RO. BOX 122, STATION A EDITORIAL ADVISOR In Transit 18 TORONTO, ONTARIO M5W 1A2 Stuart I. Westland Motive Power and Rolling Stock 19 NOTICES CALENDAR RAPID TRANSIT IN CANADA Saturday, April 13 - Forest City Railway Society 17th Annual The special theme of this month's issue of the Newsletter is SUde Trade and Sale Day, 1:00 to 5:00 p.m.. All Saints' Church, rapid transit. The entire history of rapid transit in Canada, Hamilton at Inkerman, London, Ontario. Admission $2.00, except for some of the early planning, has fallen within the 50- dealers welcome. For information, contact Ian Piatt, R.R. #3, year history of the UCRS. What is now an essential part of day- IngersoU, Ontario NSC 3J6, 519 485-2817. to-day life in the largest cities, therefore, was an innovation to Friday, April 19 - UCRS Toronto meeting, 8:00 p.m., at the our early members, and the progress of these urban railways Toronto Board of Education, 6th floor auditorium, 155 CoUege must seem remarkable in retrospect.