On Rethinking Japanese Feminisms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tohoku University 21St Century COE Program, School of Law, Tohoku University 27-1 Kawauchi, Aoba-Ku, Sendai 980-8576, Japan Tel

Third Edition,2008 TheThe TohokuTohoku UniversityUniversity 21st21st CenturyCentury COECOE ProgramProgram Gender Law and Policy Center (GELAPOC) Address : 19th Floor of AER building, 1-3-1, Chuo, Aoba-ku, Sendai City, 980-6119, Japan Telephone : +81-(0)22-723-1965 Facsimile : +81-(0)22-723-1966 E-mail : [email protected] From 1st of March 2008 New Address: School of Law Katahira 5th Building, 2-1-1, Katahira, Aoba-ku, Sendai City, Miyagi, 980-8577 Telephone : +81-(0)22-217-6132 Facsimile : +81-(0)22-217-6133 E-mail : [email protected] Website: http://www.law.tohoku.ac.jp/gelapoc/ http://www.law.tohoku.ac.jp/COE/english/index.html CCOE最終報告書_英語.inddOE最 終 報 告 書 _英 語 .in d 1d 1 008.3.118.3.11 111:18:481:18:48 AAMM プ ロ セセスシアンス シ ア ン プ ロ セセスス マ ゼゼンタン タ プ ロ セセスイス イ エエローロ ー プ ロ セセスブラックス ブ ラ ッ ク The 21st century COE program Gender Law & Policy Center Message from the COE Program Leader Established within the context of the 21st Century Centers of Excellence (COE) Program by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, the principal objective of the Gender Law and Policy Center( GELAPOC) has been to promote research on a wide variety of gender issues in order to bridge the gap between theory and practice within diverse legal, political and public policy processes. Among other contributions, the Center functions as a library, possessing over 4000 books concerning gender, law and public policy, and moreover, it serves as a networking and information hub that promotes collaboration amongst scholars, researchers and decision-makers in Asian, European, and North American academic institutions, local governments and Bar Associations. -

Feminist Studies/Activities in Japan: Present and Future

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Diposit Digital de Documents de la UAB (d) FEMINIST STUDIES/ACTIVITIES IN JAPAN: PRESENT AND FUTURE KAZUKO TAKEMURA Ochanomizu University, Japan The essay provides an overview of feminist studies in Japan nowadays, exploring in particular how new perspectives on sexuality and postcolonial theory have been gradually incorporated into feminist studies since the 1990s. In relation to sexuality, approaches to gender-sexuality have been enriched by the incorporation of new theories from areas such as literary criticism, art or history, among others. This has allowed for new critical exam- inations of heterosexism and of questions about gender and sexuality, and has eventually derived in the institutionalization of feminist studies with a poststructuralist influence in the Japanese academia. The article also analyzes the incorporation of postcolonial studies into feminist studies, as well as the impact that the question of prostitution during the war has had on them. KEY WORDS: feminist studies, Japan, sexuality, gender, postcolonialism, war and prosti- tution, postfeminism 1. Introduction What I have been asked to do here is to provide an overview of the current panorama of feminist theory in Japan. But it is not such an easy task as I first expected, because it seems we need to reexamine several concepts that are seemingly postulated as indisputable in this sort of expression. The first one is the concept of feminist “theory”. How could we differentiate between theoretical exploration and positive research, or between epistemological understanding and empirical knowledge? How can feminist theory be defined, being separated from other feminist approaches and representa- tions? The second one has to do with the adjective “Japanese”. -

THE NINTH ANNUAL ASCJ CONFERENCE PROGRAM Registration Will Begin at 9:15 A.M

THE NINTH ANNUAL ASCJ CONFERENCE PROGRAM Registration will begin at 9:15 a.m. on Saturday, June 18, 2005 All sessions will be held in the main classroom building of the Faculty of Comparative Culture at the Ichigaya campus of Sophia University. SATURDAY JUNE 18 SATURDAY MORNING SESSIONS: 10:00 A.M. – 12:00 NOON Session 1: Room 201 Images of Japanese Women: Interdisciplinary Analyses of the Persistent Paradigm Organizer / Chair: Aya Kitamura, University of Tokyo 1) Yumiko Yamamori, Bard Graduate Center A. A. Vantine and Company: Purveyor of an Image of Japan and the Japanese People, 1895- 1920 2) Aya Kitamura, University of Tokyo Gazed Upon and Gazing Back: Images and Identities of Japanese Women 3) Ruth Martin, Oxford Brookes University “Trailing Spouses” No More: The Experience of Japanese Expatriate Wives in the UK Discussant: Chizuko Ueno, University of Tokyo Session 2: Room 301 Hybridity and Authenticity: Japanese Literature in Transition Organizer / Chair: Masako Ono, Teikyo University 1) Masako Ono, Teikyo University Marginalization of Chinese, Essentialization of Japanese, and Hybridization of The Tale of Genji 2) Asako Nakai, Hitotsubashi University Hybridity, Bilingualism, Untranslatability: Mizumura Minae and the Politics of “Modern Japanese Literature” 3) Tomoko Kuribayashi, University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point Transformations Bodily and Linguistic: Tawada Yōko’s Revisions of Ovid’s Metamorphoses 4) Leith Morton, Tokyo Institute of Technology Yuta as Postcolonial Hybrid in Ōshiro Tatsuhiro’s Fiction Discussant: Yeounsuk Lee, -

Japanese Women and Critical Feminism: a Qualitative Study

Social Science Review Volume 3, Issue 1, June 2017 ISSN 2518-6825 Japanese Women and Critical Feminism: A Qualitative Study Melanie Belarmino Melinda Roberts, Ph.D. University of Southern Indiana United States Abstract Paralleling Western feminist movements, the pursuit of equal rights between the sexes by Japanese feminists have a rich and diverse history. Despite the available records of the feminist movement from its conception to its current efforts, the impacts of the movement remain unaddressed by academia, leaving out the voices of the young women whose lives are intimately affected by the accomplishments and failures of feminism. The purpose of this qualitative study is to study the perceptions of young Japanese women in college regarding their nation’s feminist movement, its successes, and its differences with American feminism. Qualitative data was collected through open-ended questions during interviews resulting in various opinions and experiences regarding the feminist movement’s influences. The feminist movement has a long history of progress regarding women‘s rights in Western nations, such as the United States, from the first wave in the twentieth century to the current modern day third wave. The fight for the equality of the sexes and for improvements regarding women‘s sociopolitical standing was not confined geographically, as Asian nations and their women have forged their own historical movements alongside Western feminism in the face of the patriarchal societies in which they live. Japan, a nation classified as a patriarchal society, is a notable place where women have to struggleagainst the gendered inequalities of a culture that is fixated on maleness. -

Introduction to Gendering Modern Japanese History Barbara Molony Santa Clara University, [email protected]

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons History College of Arts & Sciences 11-2005 Introduction to Gendering Modern Japanese History Barbara Molony Santa Clara University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.scu.edu/history Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Molony, B., & Uno, K. (2005). Introduction. In B. Molony & K. Uno (Eds.), Gendering Modern Japanese History (pp. 1–35). Harvard University Asia Center, Harvard University Press. Copyright 2005 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Do not reproduce. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright 2005 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Do not reproduce. Contents About the Contributors IX Introduction Barbara Molony and Kathleen Uno I. Gender, Selfhood, Culture I Made in Japan: Meiji Women's Education Martha Tocco 39 2 Thoughts on the Early 1Ieiji Gentleman Donald Roden 61 3 Commodifying and Engendering Morality: Self-Cultivation and the Construction of the "Ideal \X'oman" in 1920s Mass \X'omen's Magazines Barbara Sato 99 II. Genders, Bodies, Sexualities 4 "S" is for Sister: Schoolgirl Intimacy and "Same-Sex Love" in Early Twentieth-Century Japan Gregory M. Pjlugfelder 133 5 Seeds and (Nest) Eggs of Empire: Sexology Manuals/ Manual Sexology Mark Driscoll 191 6 Engendering Eugenics: Feminists and Marriage Restriction Legislation in the 1920s Sumiko Otsubo 225 III. -

Male Entertainers and the Divide Between Popular Culture and History in Japan Meradeth Lin Edwards University of San Diego

University of San Diego Digital USD Theses Theses and Dissertations Summer 8-7-2018 Professional Heartbreakers: Male Entertainers and the Divide Between Popular Culture and History in Japan Meradeth Lin Edwards University of San Diego Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/theses Part of the Asian History Commons, and the History of Gender Commons Digital USD Citation Edwards, Meradeth Lin, "Professional Heartbreakers: Male Entertainers and the Divide Between Popular Culture and History in Japan" (2018). Theses. 31. https://digital.sandiego.edu/theses/31 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Digital USD. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital USD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF SAN DIEGO Professional Heartbreakers: Male Entertainers and the Divide Between Popular Culture and History in Japan A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History by Meradeth Lin Edwards Thesis Committee Yi Sun, Ph.D., Chair Michael Gonzalez, Ph.D. 2018 The Thesis of Meradeth Lin Edwards is approved by: _________________________________________________________ Thesis Committee Chair _________________________________________________________ Thesis Committee Member University of San Diego San Diego 2018 ii Copyright 2018 Meradeth Lin Edwards Limitations: No part of this document may be reproduced in any form without the author's prior written consent for a period of three years after the date of submittal. _______________________________________ Meradeth Lin Edwards iii Dedicated to my American parents, who were undoubtedly the most enthusiastic fans of this work and are patient with my free spirit, and my Japanese parents, who instilled in me a great love of their culture, history, and lifestyle. -

Dōjinshi" Online

Transformative Works and Cultures, special issue: Transnational boys' love fan studies, No. 12 (March 15, 2013) Editorial Kazumi Nagaike & Katsuhiko Suganuma, Transnational boys' love fan studies Theory Toshio Miyake, Doing Occidentalism in contemporary Japan: Nation anthropomorphism and sexualized parody in "Axis Powers Hetalia" Björn-Ole Kamm, Rotten use patterns: What entertainment theories can do for the study of boys' love Praxis Paul M. Malone, Transplanted boys' love conventions and anti-"shota" polemics in a German manga: Fahr Sindram's "Losing Neverland" Lucy Hannah Glasspool, Simulation and database society in Japanese role-playing game fandoms: Reading boys' love "dōjinshi" online Symposium Erika Junhui Yi, Reflection on Chinese boys' love fans: An insider's view Keiko Nishimura, Where program and fantasy meet: Female fans conversing with character bots in Japan Midori Suzuki, The possibilities of research on "fujoshi" in Japan Akiko Hori, On the response (or lack thereof) of Japanese fans to criticism that "yaoi" is antigay discrimination Review Samantha Anne Close, "Mechademia Vol. 6: User Enhanced," edited by Frenchy Lunning Emerald King, "Writing the love of boys: Origins of 'bishōnen' culture in modernist Japanese literature," by Jeffrey Angles Transformative Works and Cultures (TWC), ISSN 1941-2258, is an online-only Gold Open Access publication of the nonprofit Organization for Transformative Works. TWC is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License. Download date: March 15, 2017. For citation, please refer to the most recent version of articles at TWC. Transformative Works and Cultures, Vol 12 (2013) Editorial Transnational boys' love fan studies Kazumi Nagaike and Katsuhiko Suganuma Oita University, Oita, Japan [0.1] Keywords—BL; Dōjinshi; Gender; Homosexuality; Transnationality Nagaike, Kazumi, and Katsuhiko Suganuma. -

Language and Society in Japan Nanette Gottlieb Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521532841 - Language and Society in Japan Nanette Gottlieb Frontmatter More information Language and Society in Japan Language and Society in Japan deals with issues important to an under- standing of language in Japan today, among them multilingualism, language and nationalism, technology and language, discriminatory language, and literacy and reading habits. It is organized around the theme of language and identity, in particular the role of language in constructing national, international and personal identities. Contrary to popular stereotypes, Japanese is far from the only language used in Japan, and the Japanese language itself does not function in a vacuum, but comes with its own cultural implications for native speakers. Language has played an important role in Japan’s cultural and foreign policies, and language issues have been and continue to be intimately connected both with certain globalizing technological advances and with internal minority group experiences. Nanette Gottlieb is a leading authority in this field. Her book builds on and develops her previous work on dif- ferent aspects of the sociology of language in Japan. It will be essential reading for students, scholars and all those wanting to understand the role played by language in Japanese society. nanette gottlieb is Reader in Japanese at the University of Queens- land. Her previous publications include Word Processing Technology in Japan (2000) and Japanese Cybercultures (2003). © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge -

The Reproductive Bargain Studies in Critical Social Sciences

The Reproductive Bargain Studies in Critical Social Sciences Series Editor David Fasenfest (Wayne State University) Editorial Board Eduardo Bonilla-Silva (Duke University) Chris Chase-Dunn (University of California-Riverside) William Carroll (University of Victoria) Raewyn Connell (University of Sydney) Kimberlé W. Crenshaw (University of California, la, and Columbia University) Heidi Gottfried (Wayne State University) Karin Gottschall (University of Bremen) Mary Romero (Arizona State University) Alfredo Saad Filho (University of London) Chizuko Ueno (University of Tokyo) Sylvia Walby (Lancaster University) VOLUME 77 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/scss The Reproductive Bargain Deciphering the Enigma of Japanese Capitalism By Heidi Gottfried LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: Street in Ueno, Tokyo, Japan, with in the background the National Flag of Japan; photo taken by Jason Go (Singapore) on 6 June 2013. Source: Pixabay.com. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gottfried, Heidi, 1955- The reproductive bargain : deciphering the enigma of Japanese capitalism / by Heidi Gottfried. pages cm. -- (Studies in critical social sciences, ISSN 1573-4234 ; vol. 77) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-29149-2 (hardback : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-90-04-29148-5 (e-books : alk. paper) 1. Job security--Japan--History. 2. Industrial relations--Japan--History. 3. Employees--Japan--History. 4. Labor-- Japan--History. 5. Unemployment--Japan--History. 6. Capitalism--Japan. I. Title. HD5708.45.J3G68 2015 331.0952--dc23 2015011615 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, ipa, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. -

Researching Japanese War Crimes

IWG RE Now that the files are open and accessible, it's up to us to use them to write a fuller history of Japan's wartime actions. It's an important task, and this book CRIMES WAR SEARCHING JAPANESE is the place to begin. CAROL GLUCK, George Sansom RESEARCHING Professor of History, Columbia University JAPANESE WAR CRIMES This volume will be both essential reading and a major reference tool for those interested in the war []INTRODUCTORY ESSAYS in the Pacific, United States intelligence in and after that conflict, and Japanese war crimes as known and understood at the time. GERHARD WEINBERG, Professor Emeritus of History, University of North Carolina Finally, after sixty years, our records on Japan have been indexed, and some documents that have been hiding in plain sight can now be located with superb finding aids. Pacific War veterans and their descen- dants will especially appreciate this roadmap to America's very personal war. LINDA GOETZ HOLMES, author of Unjust Enrichment: How Japan's Companies Built Postwar Fortunes Using American POWs and 4000 Bowls of Rice: A Prisoner of War Comes Home $19.95 Researching Japanese War Crimes Records Introductory Essays o Researching Japanese War Crimes Records Introductory Essays o Edward Drea Greg Bradsher Robert Hanyok James Lide Michael Petersen Daqing Yang Nazi War Crimes and Japanese Imperial Government Records Interagency Working Group Washington, DC Published by the National Archives and Records Administration for the Nazi War Crimes and Japanese Imperial Government Records Interagency Working Group, 2006 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Researching Japanese war crimes records : introductory essays / Edward Drea .. -

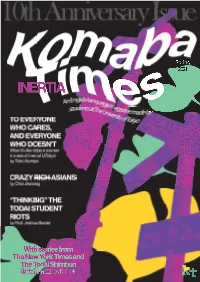

Komaba Times Publishes Issue 10

Letterfrom THE MOST MEMORABLE of human endeavors can be summed up within a few words: man reaches moon. Jackson moonwalks. Komaba Times publishes Issue 10. In this special anniversary issue, we capture a collective journey through iner- tia–a resistance to change. Although we chose this theme before the pandemic, it be- ISSUEcame all the more apt as we quarantined ourselves, suspending Nº10 any continuation of normal life. Some inertias afect the entire world, while others are contained within the dormitory rooms and 1K apartments which have become our cells. ISSUE Inertia can also describe objects that keep moving after they “stop”.Nº10 This year, through these unusual times, we’ve grown from a small, dedicated team of 8 to having 30 members and counting. Our first graphics team painstakingly created each lovely spread you’ll see. Our new business team distributed this magazine to schools and organizations all over the world. Our innovative translations department bridged the gap between ISSUEthe English-speaking and Japanese-speaking populationNº10 at UTokyo. We are also marking this anniversary issue through a special collaboration with The New York Times. We hope to not only enrich our magazine with the global coverage of the renowned publication, but also to poke our toes in the ISSUEwater and see how we dance with the bestNº10 of them. Featured articles from Todai Shimbun, our university’s longest-running newspaper, further exhibit our hybrid iden- tity. What better way to represent a thriving but almost-unrepresented bilingual audience than to feature both En- ISSUEglish and Japanese content in our Nº10pages? We’ve also revamped our magazine sections to reflect our new editorial direction. -

Gender and Construction of the Life Course

GENDER AND CONSTRUCTION OF THE LIFE COURSE OF JAPANESE IMMIGRANT WOMEN IN CANADA by NATSUKO CHUBACHI A thesis submitted to the Department of Geography in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada April, 2009 Copyright©Natsuko Chubachi, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-65423-1 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-65423-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation.