Redefining Cantonese Cuisine in Post-Mao Guangzhou1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Icons, Culture and Collective Identity of Postwar Hong Kong

Intercultural Communication Studies XXII: 1 (2013) R. MAK & C. CHAN Icons, Culture and Collective Identity of Postwar Hong Kong Ricardo K. S. MAK & Catherine S. CHAN Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong S.A.R., China Abstract: Icons, which take the form of images, artifacts, landmarks, or fictional figures, represent mounds of meaning stuck in the collective unconsciousness of different communities. Icons are shortcuts to values, identity or feelings that their users collectively share and treasure. Through the concrete identification and analysis of icons of post-war Hong Kong, this paper attempts to highlight not only Hong Kong people’s changing collective needs and mental or material hunger, but also their continuous search for identity. Keywords: Icons, Hong Kong, Hong Kong Chinese, 1997, values, identity, lifestyle, business, popular culture, fusion, hybridity, colonialism, economic takeoff, consumerism, show business 1. Introduction: Telling Hong Kong’s Story through Icons It seems easy to tell the story of post-war Hong Kong. If merely delineating the sky-high synopsis of the city, the ups and downs, high highs and low lows are at once evidently remarkable: a collective struggle for survival in the post-war years, tremendous social instability in the 1960s, industrial take-off in the 1970s, a growth in economic confidence and cultural arrogance in the 1980s and a rich cultural upheaval in search of locality before the handover. The early 21st century might as well sum up the development of Hong Kong, whose history is long yet surprisingly short- propelled by capitalism, gnawing away at globalization and living off its elastic schizophrenia. -

An Ethnography of the Spring Festival

IMAGINING CHINA IN THE ERA OF GLOBAL CONSUMERISM AND LOCAL CONSCIOUSNESS: MEDIA, MOBILITY, AND THE SPRING FESTIVAL A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Li Ren June 2003 This dissertation entitled IMAGINING CHINA IN THE ERA OF GLOBAL CONSUMERISM AND LOCAL CONSCIOUSNESS: MEDIA, MOBILITY AND THE SPRING FESTIVAL BY LI REN has been approved by the School of Interpersonal Communication and the College of Communication by Arvind Singhal Professor of Interpersonal Communication Timothy A. Simpson Professor of Interpersonal Communication Kathy Krendl Dean, College of Communication REN, LI. Ph.D. June 2003. Interpersonal Communication Imagining China in the Era of Global Consumerism and Local Consciousness: Media, Mobility, and the Spring Festival. (260 pp.) Co-directors of Dissertation: Arvind Singhal and Timothy A. Simpson Using the Spring Festival (the Chinese New Year) as a springboard for fieldwork and discussion, this dissertation explores the rise of electronic media and mobility in contemporary China and their effect on modern Chinese subjectivity, especially, the collective imagination of Chinese people. Informed by cultural studies and ethnographic methods, this research project consisted of 14 in-depth interviews with residents in Chengdu, China, ethnographic participatory observation of local festival activities, and analysis of media events, artifacts, documents, and online communication. The dissertation argues that “cultural China,” an officially-endorsed concept that has transformed a national entity into a borderless cultural entity, is the most conspicuous and powerful public imagery produced and circulated during the 2001 Spring Festival. As a work of collective imagination, cultural China creates a complex and contested space in which the Chinese Party-state, the global consumer culture, and individuals and local communities seek to gain their own ground with various strategies and tactics. -

Language Kinship Between Mandarin, Hokkien Chinese and Japanese (Lexicostatistics Review)

LANGUAGE KINSHIP BETWEEN MANDARIN, HOKKIEN CHINESE AND JAPANESE (LEXICOSTATISTICS REVIEW) KEKERABATAN ANTARA BAHASA MANDARIN, HOKKIEN DAN JEPANG (TINJAUAN LEXICOSTATISTICS) Abdul Gapur1, Dina Shabrina Putri Siregar 2, Mhd. Pujiono3 1,2,3Faculty of Cultural Sciences, University of Sumatera Utara Jalan Universitas, No. 19, Medan, Sumatera Utara, Indonesia Telephone (061) 8215956, Facsimile (061) 8215956 E-mail: [email protected] Article accepted: July 22, 2018; revised: December 18, 2018; approved: December 24, 2018 Permalink/DOI: 10.29255/aksara.v30i2.230.301-318 Abstract Mandarin and Hokkien Chinese are well known having a tight kinship in a language family. Beside, Japanese also has historical relation with China in the field of language and cultural development. Japanese uses Chinese characters named kanji with certain phonemic vocabulary adjustment, which is adapted into Japanese. This phonemic adjustment of kanji is called Kango. This research discusses about the kinship of Mandarin, Hokkien Chinese in Indonesia and Japanese Kango with lexicostatistics review. The method used is quantitative with lexicostatistics technique. Quantitative method finds similar percentage of 100-200 Swadesh vocabularies. Quantitative method with lexicostatistics results in a tree diagram of the language genetics. From the lexicostatistics calculation to the lexicon level, it is found that Mandarin Chinese (MC) and Japanese Kango (JK) are two different languages, because they are in a language group (stock) (29%); (2) JK and Indonesian Hokkien Chinese (IHC) are also two different languages, because they are in a language group (stock) (24%); and (3) MC and IHC belong to the same language family (42%). Keywords: language kinship, Mandarin, Hokkien, Japanese Abstrak Bahasa Mandarin dan Hokkien diketahui memiliki hubungan kekerabatan dalam rumpun yang sama. -

China in 50 Dishes

C H I N A I N 5 0 D I S H E S CHINA IN 50 DISHES Brought to you by CHINA IN 50 DISHES A 5,000 year-old food culture To declare a love of ‘Chinese food’ is a bit like remarking Chinese food Imported spices are generously used in the western areas you enjoy European cuisine. What does the latter mean? It experts have of Xinjiang and Gansu that sit on China’s ancient trade encompasses the pickle and rye diet of Scandinavia, the identified four routes with Europe, while yak fat and iron-rich offal are sauce-driven indulgences of French cuisine, the pastas of main schools of favoured by the nomadic farmers facing harsh climes on Italy, the pork heavy dishes of Bavaria as well as Irish stew Chinese cooking the Tibetan plains. and Spanish paella. Chinese cuisine is every bit as diverse termed the Four For a more handy simplification, Chinese food experts as the list above. “Great” Cuisines have identified four main schools of Chinese cooking of China – China, with its 1.4 billion people, has a topography as termed the Four “Great” Cuisines of China. They are Shandong, varied as the entire European continent and a comparable delineated by geographical location and comprise Sichuan, Jiangsu geographical scale. Its provinces and other administrative and Cantonese Shandong cuisine or lu cai , to represent northern cooking areas (together totalling more than 30) rival the European styles; Sichuan cuisine or chuan cai for the western Union’s membership in numerical terms. regions; Huaiyang cuisine to represent China’s eastern China’s current ‘continental’ scale was slowly pieced coast; and Cantonese cuisine or yue cai to represent the together through more than 5,000 years of feudal culinary traditions of the south. -

{Download PDF} Jakarta: 25 Excursions in and Around the Indonesian Capital Ebook, Epub

JAKARTA: 25 EXCURSIONS IN AND AROUND THE INDONESIAN CAPITAL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Andrew Whitmarsh | 224 pages | 20 Dec 2012 | Tuttle Publishing | 9780804842242 | English | Boston, United States Jakarta: 25 Excursions in and around the Indonesian Capital PDF Book JAKARTA, Indonesia -- A jet carrying 62 people lost contact with air traffic controllers minutes after taking off from Indonesia's capital on a domestic flight on Saturday, and debris found by fishermen was being examined to see if it was from the missing plane, officials said. Bingka Laksa banjar Pekasam Soto banjar. Recently, she spent several months exploring Africa and South Asia. The locals always have a smile on their face and a positive outlook. This means that if you book your accommodation, buy a book or sort your insurance, we earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. US Capitol riots: Tracking the insurrection. The Menteng and Gondangdia sections were formerly fashionable residential areas near the central Medan Merdeka then called Weltevreden. Places to visit:. We'll assume you're ok with this, but you can opt-out if you wish. Some traditional neighbourhoods can, however, be identified. Tis' the Season for Holiday Drinks. What to do there: Eat, sleep, and be merry. Special interest tours include history walks, urban art walks and market walks. Rujak Rujak cingur Sate madura Serundeng Soto madura. In our book, that definitely makes it worth a visit. Jakarta, like any other large city, also has its share of air and noise pollution. We work hard to put out the best backpacker resources on the web, for free! Federal Aviation Administration records indicate the plane that lost contact Saturday was first used by Continental Airlines in Articles from Britannica Encyclopedias for elementary and high school students. -

Food Security and Nutrition in the Age of Climate Change

Food Security and Nutrition in the Age of Climate Change Proceedings of the International Symposium organized by the government of Québec in collaboration with FAO Québec City, September 24-27, 2017 IN COLLABORATION WITH Food Security and Nutrition in the Age of Climate Change PROCEEDINGS OF THE INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZED BY THE GOVERNMENT OF QUÉBEC IN COLLABORATION WITH FAO Québec City, September 24-27, 2017 Edited by Alexandre Meybeck Elizabeth Laval Rachel Lévesque Geneviève Parent FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2018 Meybeck, A., Laval, E., Lévesque, R., Parent, G., 2018. Food Security and Nutrition in the Age of Climate Change.Proceedings of the International Symposium organized by the Government of Québec in collaboration with FAO. Québec City, September 24-27, 2017. Rome, FAO. pp. 132. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. -

Radio Television Hong Kong

RADIO TELEVISION HONG KONG PERFORMANCE PLEDGE This leaflet summarizes the services provided by Radio Television Hong Kong (RTHK) and the standards you can expect. It also explains the steps you can take if you have a comment or a complaint. 1. Hong Kong's Public Broadcaster RTHK is the sole public broadcaster in the HKSAR. Its primary obligation is to serve all audiences - including special interest groups - by providing diversified radio, television and internet services that are distinctive and of high quality, in news and current affairs, arts, culture and education. RTHK is editorially independent and its productions are guided by professional standards set out in the RTHK Producers’ Guidelines. Our Vision To be a leading public broadcaster in the new media environment Our Mission To inform, educate and entertain our audiences through multi-media programming To provide timely, impartial coverage of local and global events and issues To deliver programming which contributes to the openness and cultural diversity of Hong Kong To provide a platform for free and unfettered expression of views To serve a broad spectrum of audiences and cater to the needs of minority interest groups 2. Corporate Initiatives In 2010-11, RTHK will continue to enhance participation by stakeholders and the general public with a view to strengthening transparency and accountability; maximize return on government funding by further enhancing cost efficiency and productivity; continue to ensure staff handle public funds in a prudent and cost-effective manner; actively explore opportunities in generating revenue for the government from RTHK programmes and contents; provide media coverage and produce special radio, television programmes and related web content for Legislative Council By-Elections 2010, Shanghai Expo 2010, 2010 Asian Games in Guangzhou and World Cup in South Africa; and carry out the preparatory work for launching the new digital audio broadcasting and digital terrestrial television services to achieve its mission as the public service broadcaster. -

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY of ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University Ofhong Kong

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY OF ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University ofHong Kong Asia today is one ofthe most dynamic regions ofthe world. The previously predominant image of 'timeless peasants' has given way to the image of fast-paced business people, mass consumerism and high-rise urban conglomerations. Yet much discourse remains entrenched in the polarities of 'East vs. West', 'Tradition vs. Change'. This series hopes to provide a forum for anthropological studies which break with such polarities. It will publish titles dealing with cosmopolitanism, cultural identity, representa tions, arts and performance. The complexities of urban Asia, its elites, its political rituals, and its families will also be explored. Dangerous Blood, Refined Souls Death Rituals among the Chinese in Singapore Tong Chee Kiong Folk Art Potters ofJapan Beyond an Anthropology of Aesthetics Brian Moeran Hong Kong The Anthropology of a Chinese Metropolis Edited by Grant Evans and Maria Tam Anthropology and Colonialism in Asia and Oceania Jan van Bremen and Akitoshi Shimizu Japanese Bosses, Chinese Workers Power and Control in a Hong Kong Megastore WOng Heung wah The Legend ofthe Golden Boat Regulation, Trade and Traders in the Borderlands of Laos, Thailand, China and Burma Andrew walker Cultural Crisis and Social Memory Politics of the Past in the Thai World Edited by Shigeharu Tanabe and Charles R Keyes The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I PRESS HONOLULU Editorial Matter © 2002 David Y. -

Chinese-Language Media Outlets

澳大利亚-中国关系研究院 CHINESE-LANGUAGE MEDIA IN AUSTRALIA: Developments, Challenges and Opportunities Professor Wanning Sun Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences University of Technology Sydney FRONT COVER IMAGE: Ming Liang Published by the Australia-China Relations Institute (ACRI) Level 7, UTS Building 11 81 - 115 Broadway, Ultimo NSW 2007 t: +61 2 9514 8593 f: +61 2 9514 2189 e: [email protected] © The Australia-China Relations Institute (ACRI) 2016 ISBN 978-0-9942825-6-9 The publication is copyright. Other than for uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without attribution. CONTENTS List of Figures 4 Executive Summary 5 Overview 5 Recommendations 8 Challenges and opportunities 10 Future research 11 Introduction 13 History of Chinese Media in Australia 15 Trends and Recent Developments in the Sector 22 Major Chinese Media (by Sector) 26 Daily paid newspapers 28 Television 28 Radio 28 Online media 29 Access to Major Chinese Media Outlets (by Region) 31 Patterns of Media Consumption 37 The Growth of Social Media Use and WeChat 44 Recommendations for Government, Business and Mainstream Media 49 Challenges and Opportunities 54 Pathways to Future Research 59 References 63 Appendix 67 Appendix A: Circulation Figures (Chinese-language Print Publications in Australia) 67 About ACRI 70 About the Author 71 CHINESE-LANGUAGE MEDIA IN AUSTRALIA 3 LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1. Media sectors currently targeting Chinese migrants in Australia. 21 Figure 2. Time spent with media (hours per week) by Chinese in Australia aged 14-74 years, compared to overall Australian population. 37 Figure 3. -

Nutrition and Baseline Survey of Older People in Haraze Albiar, Chad, June 2012

Nutrition and baseline survey of older people in Haraze Albiar, Chad, June 2012 HelpAge International helps older people claim their rights, challenge discrimination and overcome poverty, so that they can lead dignified, secure, active and healthy lives. Acknowledgements Many thanks to the staff of the Merlin Emergency Response Team in London, N’Djamena and Massaguet for their help and support during this survey. We are very grateful to the people who helped us to implement the survey in the Haraze Albiar District: the District Health Authorities (Dr Amane Koumaye and the District Health Team), the administrative authorities (the Haraze Albiar Prefect and the Mayor of Masssaguet). Special thanks to Jacques Kipala from HelpAge International Goma, who helped to supervise the survey. Thanks to the nine surveyors who carried out the survey in the district. Most importantly, thanks to the 721 older women and men in the Haraze Albiar district, who agreed to be interviewed, measured and sometimes photographed for this survey. The donor for this project is the Global Emergency Fund (Age UK). Nutrition and baseline survey of older people in Haraze Albiar, Chad, June 2012 Published by HelpAge International HelpAge International PO Box 70156 London WC1A 9GB, UK [email protected] www.helpage.org Copyright © 2012 HelpAge International Registered charity no. 288180 Written by Dr Pascale Fritsch, Emergency Health and Nutrition Adviser, HelpAge International with Mark Myatt, Consultant Epidemiologist, Brixton Health. Front and back cover photos: Interviewing older people in Haraze Albiar, June 2012 Photos © HelpAge International Any parts of this publication may be reproduced without permission for non-profit and educational purposes unless indicated otherwise. -

A Cantonese Opera Based on a Midsummer Night's Dream

A Dream in Fantasia — A Cantonese Opera Based on A Midsummer Night's Dream Loretta Ling Yeung, Hong Kong and Augusta, Georgia USA Abstract This review discusses an appropriation of A Midsummer Night's Dream by the Hong Kong Young Talent Cantonese Opera Troupe. While retaining most of Shakespeare's characters and his basic plot structure, the new opera, A Dream in Fantasia, aimed to expand the audience for Cantonese opera. At the same time it proved to be transparently entertaining to its Cantonese audience. A Dream in Fantasia (adapted from William Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream), with a new script by Keith Lai. Hong Kong Young Talent Cantonese Opera Troupe. Director, Lee Lung. Cast: Lam Tin-Yao as Linghu Feng (Demetrius); Doris Kwan as Xiahou Jun (Lysander); Lam Tsz-Ching as Yuwen Piaopiao (Hermia); Cheng Nga-Kei as Murong Xiangxiang (Helena); guest artist Kwok Kai-Fai as Crown Prince Gongyang (Oberon); guest artist Leung Wai-Hong as the Crown Princess (Titania); Hong Wah as the Forest Fairy (Puck); Wong Kit-Ching as Shangguan Chan (Peter Quince); Yuen Seen-Ting as Zhuge Zi (Bottom); Keith Lai as Chanyu Xiong 2 Borrowers and Lenders (Egeus); and Wong Po-Hyun as Queen Xuanyuan (Hippolyta). Tsuen Wan City Hall Auditorium, Hong Kong, 14 December 2013. As I enter the theater at the City Hall of Tsuen Wan, a suburb of Hong Kong, the audience — predominantly elderly people and women — is eagerly waiting to watch A Midsummer Night's Dream in a Cantonese version, entitled A Dream in Fantasia (figure 1).1 At stage right, a small Chinese orchestra is about take us to Fairyland, where four confused young lovers will try to find true love, while a group of villagers prepare a show for the Queen's birthday. -

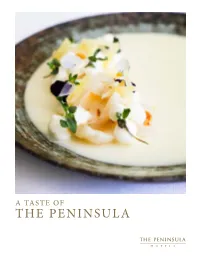

A Taste of the Peninsula Cookbook

A TASTE OF THE PENINSULA ABOUT THIS COOKBOOK Over the years, many visitors and guests have enjoyed TABLE OF CONTENTS the delicious cuisine and libations offered across The Peninsula Hotels, which is often missed once BREAKFAST they have returned home. This special collection Fluffy Egg-White Omelette – The Peninsula Tokyo 2 of signature recipes, selected by award-winning Peninsula chefs and mixologists, has been created with these guests in mind. SOUP Chilled Spring Lettuce Soup – The Peninsula Shanghai 4 These recipes aim to help The Peninsula guests recreate the moments and memories of their SALADS AND APPETISERS favourite Peninsula properties at home. The Stuffed Pepper and Mushroom Parmesan – The Peninsula Shanghai 6 collection includes light and healthy dishes from Heritage Grain Bowl – The Peninsula New York 7 The Lobby; rich, savoury Cantonese preparations Charred Caesar Salad – The Peninsula Beverly Hills 8 from one of The Peninsula Hotels’ Michelin-starred restaurants; and decadent pastries and desserts that evoke the cherished tradition of The Peninsula CHINESE DISHES Afternoon Tea. Cocktail recipes are also included, Barbecued Pork – The Peninsula Hong Kong 10 with which guests can revisit the flavours of Chive Dumplings – The Peninsula Shanghai 11 signature Peninsula tipples. Steamed Bean Curd with XO Sauce – The Peninsula Beijing 12 Summer Sichuan Chicken – The Peninsula Tokyo 13 By gathering these recipes, The Peninsula Hotels Fried Rice with Shrimp – The Peninsula Bangkok 14 aims to share a few of its closely guarded culinary