Volume 29 # June 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Statistical Analysis of Mountaineering in the Nepal Himalaya

The Himalaya by the Numbers A Statistical Analysis of Mountaineering in the Nepal Himalaya Richard Salisbury Elizabeth Hawley September 2007 Cover Photo: Annapurna South Face at sunrise (Richard Salisbury) © Copyright 2007 by Richard Salisbury and Elizabeth Hawley No portion of this book may be reproduced and/or redistributed without the written permission of the authors. 2 Contents Introduction . .5 Analysis of Climbing Activity . 9 Yearly Activity . 9 Regional Activity . .18 Seasonal Activity . .25 Activity by Age and Gender . 33 Activity by Citizenship . 33 Team Composition . 34 Expedition Results . 36 Ascent Analysis . 41 Ascents by Altitude Range . .41 Popular Peaks by Altitude Range . .43 Ascents by Climbing Season . .46 Ascents by Expedition Years . .50 Ascents by Age Groups . 55 Ascents by Citizenship . 60 Ascents by Gender . 62 Ascents by Team Composition . 66 Average Expedition Duration and Days to Summit . .70 Oxygen and the 8000ers . .76 Death Analysis . 81 Deaths by Peak Altitude Ranges . 81 Deaths on Popular Peaks . 84 Deadliest Peaks for Members . 86 Deadliest Peaks for Hired Personnel . 89 Deaths by Geographical Regions . .92 Deaths by Climbing Season . 93 Altitudes of Death . 96 Causes of Death . 97 Avalanche Deaths . 102 Deaths by Falling . 110 Deaths by Physiological Causes . .116 Deaths by Age Groups . 118 Deaths by Expedition Years . .120 Deaths by Citizenship . 121 Deaths by Gender . 123 Deaths by Team Composition . .125 Major Accidents . .129 Appendix A: Peak Summary . .135 Appendix B: Supplemental Charts and Tables . .147 3 4 Introduction The Himalayan Database, published by the American Alpine Club in 2004, is a compilation of records for all expeditions that have climbed in the Nepal Himalaya. -

Artur Hajzer, 1962–2013

AAC Publications Artur Hajzer, 1962–2013 Artur Hajzer, one of Poland’s best high-altitude climbers from the “golden age,” was killed while retreating from Gasherbrum I on July 7, 2013. He was 51. Born on June 28, 1962, in the Silesia region of Poland, Artur graduated from the University of Katowice with a degree in cultural studies. His interests in music, history, and art remained important throughout his life. He started climbing as a boy and soon progressed to increasingly difficult routes in the Tatras and the Alps, in both summer and winter, in preparation for his real calling: Himalayan climbing. He joined the Katowice Mountain Club, along with the likes of Jerzy Kukuczka, Krzysztof Wielicki, Ryszard Pawlowski, and Janusz Majer. His Himalayan adventures began at the age of 20, with expeditions to the Rolwaling Himal, to the Hindu Kush, and to the south face of Lhotse. Although the Lhotse expedition was unsuccessful, it was the beginning of his climbing partnership with Jerzy Kukuczka. Together they did the first winter ascent of Annapurna in 1987, a new route up the northeast face of Manaslu, and a new route on the east ridge of Shishapangma. Artur climbed seven 8,000-meter peaks and attempted the south face of Lhotse three times, reaching 8,300 meters on the formidable face. He even concocted a plan to climb all 14 8,000-meter peaks in one year, a scheme that was foiled by Pakistani officials when they refused him the required permits. Artur proved he was more than a climber when he organized the massively complicated “thunderbolt” rescue operation on Everest’s West Ridge, a disaster in which five members of a 10-member Polish team were killed. -

Layout 1 Copy

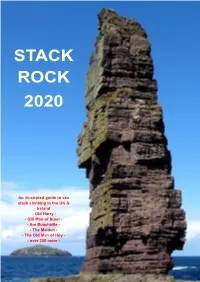

STACK ROCK 2020 An illustrated guide to sea stack climbing in the UK & Ireland - Old Harry - - Old Man of Stoer - - Am Buachaille - - The Maiden - - The Old Man of Hoy - - over 200 more - Edition I - version 1 - 13th March 1994. Web Edition - version 1 - December 1996. Web Edition - version 2 - January 1998. Edition 2 - version 3 - January 2002. Edition 3 - version 1 - May 2019. Edition 4 - version 1 - January 2020. Compiler Chris Mellor, 4 Barnfield Avenue, Shirley, Croydon, Surrey, CR0 8SE. Tel: 0208 662 1176 – E-mail: [email protected]. Send in amendments, corrections and queries by e-mail. ISBN - 1-899098-05-4 Acknowledgements Denis Crampton for enduring several discussions in which the concept of this book was developed. Also Duncan Hornby for information on Dorset’s Old Harry stacks and Mick Fowler for much help with some of his southern and northern stack attacks. Mike Vetterlein contributed indirectly as have Rick Cummins of Rock Addiction, Rab Anderson and Bruce Kerr. Andy Long from Lerwick, Shetland. has contributed directly with a lot of the hard information about Shetland. Thanks are also due to Margaret of the Alpine Club library for assistance in looking up old journals. In late 1996 Ben Linton, Ed Lynch-Bell and Ian Brodrick undertook the mammoth scanning and OCR exercise needed to transfer the paper text back into computer form after the original electronic version was lost in a disk crash. This was done in order to create a world-wide web version of the guide. Mike Caine of the Manx Fell and Rock Club then helped with route information from his Manx climbing web site. -

Mountaineering War and Peace at High Altitudes

Mountaineering War and Peace at High Altitudes 2–5 Sackville Street Piccadilly London W1S 3DP +44 (0)20 7439 6151 [email protected] https://sotherans.co.uk Mountaineering 1. ABBOT, Philip Stanley. Addresses at a Memorial Meeting of the Appalachian Mountain Club, October 21, 1896, and other 2. ALPINE SLIDES. A Collection of 72 Black and White Alpine papers. Reprinted from “Appalachia”, [Boston, Mass.], n.d. [1896]. £98 Slides. 1894 - 1901. £750 8vo. Original printed wrappers; pp. [iii], 82; portrait frontispiece, A collection of 72 slides 80 x 80mm, showing Alpine scenes. A 10 other plates; spine with wear, wrappers toned, a good copy. couple with cracks otherwise generally in very good condition. First edition. This is a memorial volume for Abbot, who died on 44 of the slides have no captioning. The remaining are variously Mount Lefroy in August 1896. The booklet prints Charles E. Fay’s captioned with initials, “CY”, “EY”, “LSY” AND “RY”. account of Abbot’s final climb, a biographical note about Abbot Places mentioned include Morteratsch Glacier, Gussfeldt Saddle, by George Herbert Palmer, and then reprints three of Abbot’s Mourain Roseg, Pers Ice Falls, Pontresina. Other comments articles (‘The First Ascent of Mount Hector’, ‘An Ascent of the include “Big lunch party”, “Swiss Glacier Scene No. 10” Weisshorn’, and ‘Three Days on the Zinal Grat’). additionally captioned by hand “Caution needed”. Not in the Alpine Club Library Catalogue 1982, Neate or Perret. The remaining slides show climbing parties in the Alps, including images of lady climbers. A fascinating, thus far unattributed, collection of Alpine climbing. -

Nepali Times Welcomes Feedback

#351 1 - 7 June 2007 16 pages Rs 30 “Maybe I will still find him,” Ram Krishni Chaudhary says, but from the Weekly Internet Poll # 351 tone of her voice one can tell she has very The number of Q. Should all sides cut their losses and let Melamchi die? little hope. It has been nearly four years since her Nepalis still listed Total votes: 2,810 25-year-old son, Bhaban, left for work in India. He was picked up by soldiers from as disappeared the Chisapani Barracks along with seven other young men and never seen again. during the war One of the seven was later released because he was related to a soldier. 937 Weekly Internet Poll # 352. To vote go to: www.nepalitimes.com According to his testimony, they were Q. How do you rate the performance of the interim government since it was made to lie down in the back of a installed two months ago? military truck underneath sacks on top of which the soldiers sat. They were severely tortured. Under pressure from the National Human Rights Commission, the army finally disclosed in 2004 that three of the detained had been killed in an “encounter”. The army said it didn’t know about the other three. “There is now an interim government, maybe someone will tell me where my son is,” Ram Krishni said recently in Nepalganj where she inaugurated the nepa-laya exhibition by unveiling her own portrait. One year after the ceasefire, Bhaban is among 937 people still officially listed as missing by the International Committee of the Red Cross. -

The Boardman Tasker Prize 2011

The Boardman Tasker Prize 2011 Adjudication by Barry Imeson I would like to start by thanking my two distinguished co-judges, Lindsay Griffin and Bernard Newman, for ensuring that we have all arrived at this year’s award in good health and still on speaking terms. We met at the BMC on 9 September to agree a shortlist based on what, in our view, constituted ‘mountain literature’ and what also met the Award criterion of being an original work that made an outstanding contribution to mountain literature. We then considered the twenty three books that had been entered and, with no small difficulty, produced a shortlist of five. We would like to start with the non-shortlisted books. As judges we were conscious of the effort required to write a book and we want to thank all the authors who provided such a variety of enjoyable, and often thought-provoking, reads. We were, however, particularly impressed by two books, which though not shortlisted, we believe have made welcome additions to the history of mountaineering. The first of these was Prelude to Everest by Ian Mitchell & George Rodway. Their book sheds new light on the correspondence between Hinks and Collie and includes Kellas’s neglected 1920 paper A Consideration of the Possibility of Ascending Mount Everest. This is a long overdue and serious attempt to re-habilitate Kellas, a modest and self-effacing man. Kellas was an important mountaineer, whose ascent of Pauhunri in North East Sikkim was, at that time, the highest summit in the world trodden by man. His research into the effects of altitude on climbers was ahead of its time. -

Od Redakcji Aktualności

04 / 2019 Od Redakcji W bieżącym numerze (https://www.kw.warszawa.pl/echa-gor) znajdziecie wspomnienia rocznicowe i garść tegorocznych wieści z gór najwyższych, informacje o arcyciekawej konferencji „Góry- Literatura-Kultura” i serii wydawniczej Pracowni Badań Humanistycznych nad Kulturą Górską, pożegnania i wspomnienia o Tych, którzy odeszli. Wszystkim czytelnikom życzymy wesoło spędzonych Świąt Bożego Narodzenia i przesyłamy dobre życzenia na Nowy Rok 2020! Anna Okopińska, Beata Słama i Marcin Wardziński Aktualności „Nazywam się Paweł Juszczyszyn, jestem sędzią Sądu Rejonowego w Olsztynie, do wczoraj delegowanym do orzekania w Sądzie Okręgowym w Olsztynie. W związku z odwołaniem mnie z delegacji do Sądu Okręgowego chcę podkreślić, że prawo stron do rzetelnego procesu jest dla mnie ważniejsze od mojej sytuacji zawodowej. Sędzia nie może bać się polityków, nawet jeśli mają wpływ na jego karierę. Apeluję do koleżanek i kolegów sędziów, aby zawsze pamiętali o rocie ślubowania sędziowskiego, orzekali niezawiśle i odważnie.” Czy wiedzieliście, że Paweł jest alpinistą? Był prezesem KW Olsztyn i uczestniczył w wielu ciekawych wyprawach. Wspiął się m.in. na Denali i Nevado Alpamayo. I czy ktoś powie, że wspinanie nie kształtuje charakterów? *** 11 grudnia 2019, podczas 14. sesji komitetu UNESCO na Listę reprezentatywną niematerialnego dziedzictwa ludzkości wpisano alpinizm. 1 40 lat temu Rakaposhi 1979 W dniach 1, 2 i 5 lipca 1979 polsko-pakistańska wyprawa w Karakorum dokonała drugiego, trzeciego i czwartego wejścia na szczyt Rakaposhi (7788 m). Jej kierownikiem był kapitan (obecnie pułkownik) Sher Khan, kierownikiem sportowym Ryszard Kowalewski, a uczestnikami Andrzej Bieluń, Anna Czerwińska, Jacek Gronczewski (lekarz), Krystyna Palmowska, Tadeusz Piotrowski, Jerzy Tillak i wspinacze pakistańscy. Sukces został ładnie podsumowany przez Janusza Kurczaba: „Choć wyprawa obfitowała w konflikty, zarówno na linii Pakistańczycy – Polacy, jak i między grupą męską a dwójką kobiet, to efekt końcowy był bardzo korzystny. -

2000 Ladakh and Zanskar-The Land of Passes

1 LADAKH AND ZANSKAR -THE LAND OF PASSES The great mountains are quick to kill or maim when mistakes are made. Surely, a safe descent is as much a part of the climb as “getting to the top”. Dead men are successful only when they have given their lives for others. Kenneth Mason, Abode of Snow (p. 289) The remote and isolated region of Ladakh lies in the state of Jammu and Kashmir, marking the western limit of the spread of Tibetan culture. Before it became a part of India in the 1834, when the rulers of Jammu brought it under their control, Ladakh was an independent kingdom closely linked with Tibet, its strong Buddhist culture and its various gompas (monasteries) such as Lamayuru, Alchi and Thiksey a living testimony to this fact. One of the most prominent monuments is the towering palace in Leh, built by the Ladakhi ruler, Singe Namgyal (c. 1570 to 1642). Ladakh’s inhospitable terrain has seen enough traders, missionaries and invading armies to justify the Ladakhi saying: “The land is so barren and the passes are so high that only the best of friends or worst of enemies would want to visit us.” The elevation of Ladakh gives it an extreme climate; burning heat by day and freezing cold at night. Due to the rarefied atmosphere, the sun’s rays heat the ground quickly, the dry air allowing for quick cooling, leading to sub-zero temperatures at night. Lying in the rain- shadow of the Great Himalaya, this arid, bare region receives scanty rainfall, and its primary source of water is the winter snowfall. -

Indian Mountaineering Foundation Newsletter * Volume 8 * November 2018

Apex Indian Mountaineering Foundation Newsletter * Volume 8 * November 2018 Anne Gilbert Chase starting out on day 2. Nilkanth Southwest face, first ascent. Image courtesy: Jason Templeton. Climbers and porters at Tapovan with the Bhagarathi peaks behind. Image courtesy: Guy Buckingham Inside Apex Volume 8 Expedition Reports Jahnukot, Garhwal Himalaya, First Ascent - Malcolm Bass President Col. H. S. Chauhan Nilkanth, Garhwal Himalaya, First Ascent by Southwest Face - Chantal Astorga & Anne Chase Vice Presidents Saser Kangri IV, Kashmir Himalaya - Basanta Kr. Singha Roy AVM A K Bhattacharya Sukhinder Sandhu Special Feature Honorary Secretary Col Vijay Singh Western Himalayan Traverse - Bharat Bhushan Honorary Treasurer Treks and Explorations S. Bhattacharjee Green Lakes, Sikkim - Ahtushi Deshpande Governing Council Members Wg Cdr Amit Chowhdury Maj K S Dhami Manik Banerjee At the Indian Mountaineering Foundation Sorab D N Gandhi Brig M P Yadav Silver Jubilee celebrations: 1993 Women’s Expedition to Everest Mahavir Singh Thakur IMF Mountain Film Festival India Tour Yambem Laba Ms Reena Dharamshaktu IMF News Col S C Sharma Keerthi Pais Ms Sushma Nagarkar In the Indian Himalaya Ex-Officio Members News and events in the Indian Himalaya Secretary/Nominee, Ministry of Finance Book Releases Secretary/Nominee, Ministry of Youth Affairs & Recent books released on the Indian Himalaya Sports Expedition Notes Apex IMF Newsletter Volume 8 Jahnukot (6805m) First Ascent Garhwal Himalaya Jahnukot, Southwest Buttress. Image courtesy: Hamish Frost Malcolm Bass describes his recent climb of Jahnukot, Garhwal Himalaya, along with Guy Buckingham and Paul Figg. This was the First Ascent of this challenging mountain. The trio climbed via the Southwest Buttress onto the South Ridge. -

Modeling Wildfire Hazard in the Western Hindu Kush-Himalayas

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Spring 2012 Modeling Wildfire Hazard in the Western Hindu Kush-Himalayas David Bylow San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Bylow, David, "Modeling Wildfire Hazard in the Western Hindu Kush-Himalayas" (2012). Master's Theses. 4126. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.vaeh-q8zw https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/4126 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MODELING WILDFIRE HAZARD IN THE WESTERN HINDU KUSH-HIMALAYAS A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Geography San José State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by: David Bylow May 2012 © 2012 David Bylow ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Designated Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis Titled MODELING WILDFIRE HAZARD IN THE WESTERN HINDU KUSH-HIMALAYAS by David Bylow APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY May 2012 Dr. Gary Pereira Department of Geography Dr. Craig Clements Department of Meteorology Dr. Jianglong Zhang University of North Dakota Dr. Yong Lao California State University Monterey Bay ABSTRACT MODELING WILDFIRE HAZARD IN THE WESTERN HINDU KUSH-HIMALAYAS by David Bylow Wildfire regimes are a leading driver of global environmental change affecting diverse ecosystems across the planet. The objectives of this study were to model regional wildfire potential and identify environmental, topological, and sociological factors that contribute to the ignition of regional wildfire events in the Western Hindu Kush-Himalayas. -

DOTTORATO DI RICERCA in Scienze Della Terra, Della Vita E Dell'ambiente

Alma Mater Studiorum – Università di Bologna DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN Scienze della terra, della vita e dell’ambiente Ciclo XXX Settore Concorsuale: 05/B1 - Zoologia e Antropologia Settore Scientifico Disciplinare: BIO/08 - Antropologia Unraveling the combined effects of demography and natural selection in shaping the genomic background of Southern Himalayan populations Presentata da Guido Alberto Gnecchi Ruscone Coordinatore Dottorato Supervisore Prof. Giulio Viola Dott. Marco Sazzini Esame finale anno 2018 Table of contents Abstract 1 1. Introduction 3 1.1 Molecular Anthropology and the study of the genetic bases of human biodiversity 3 1.1.1 Studies based on uniparental genetic markers 3 1.1.2 Studies based on autosomal genome-wide markers 5 1.2 The Southern route hypothesis and the first peopling of the Asian continent 7 1.3 The genetic history of South Asian populations 8 1.4 The peopling of East Asia: southern and northern routes 11 1.5 Historical migrations in East Asia 13 1.6 The spread of Tibeto-Burman populations 15 1.7 The peopling of the Tibetan Plateau and its adaptive implications 19 1.7.1 Archeological evidence for the peopling of the Tibetan Plateau 19 1.7.2 Genetic evidence for the peopling of the Tibetan Plateau 21 1.7.3 Adaptive implications related to the peopling of the Tibetan Plateau 22 1.8 The Nepalese Tibeto-Burman populations 23 1.9 High altitude adaptation: the Himalayan case study 24 2. Aim of the study 29 3. Materials and Methods 31 3.1 Sampling campaigns and populations studied 31 3.2 Molecular analyses 35 -

Das Wetter-Phänomen Ohne Ihn Hätte Es in Den Letzten Zehn Jahren Viel Weniger Erfolge an Den Bergen Der Welt Gegeben – Und Wahrscheinlich Mehr Tote

DAV Panorama 1/2012 as sich beim Höhenbergsteigen am stärks es ihm dabei gegangen sein? Und wie erst, als Simone und ten verändert hat in den letzten Jahren, wer Denis auf dem Weg zum Gipfel waren? Zu wissen, dass de ich manchmal gefragt. Es sind nicht Quan am nächsten Tag das Wetterfenster wieder zu ist – dass der tensprünge bei der Ausrüstung, nein: Die größte Windchill mit minus 70 Grad Celsius wirkt. Ich möchte WVeränderung hat sich beim Wetter ergeben. Nicht besser oder nicht in seiner Haut gesteckt haben. schlechter ist es geworden, wahrscheinlich insgesamt etwas wärmer; aber wir wissen inzwischen sehr viel früher und ge nauer, was da auf uns runterhageln oder schneien wird. Durchblick in der Datenflut Einer, der zur immensen Weiterentwicklung bei der Am 26. Juli 2009 schrieb Charly uns ins K2Basislager, wo Einschätzung des Bergwetters maßgeblich beigetragen hat, meine Frau Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner mit unserem Freund und der damit in den letzten zehn Jahren weltweit als der David Göttler gerade im Aufstieg in Richtung K2 war: „Lie BergwetterExperte größte Anerkennung gefunden hat, ist ber Ralf, wie bin ich froh, dass das Wetter passt. Vergangene Dr. Karl Gabl, den ich seit meiner BergführerAusbildung Nacht war ich nervös, weil die Radiosonde in Tibet noch wie alle seine Freunde mit „Charly“ ansprechen darf. relativ starken Wind meldete. Nun heißt es für mich fest Welche Bedeutung eine präzise Wettervorhersage – und die Daumen halten.“ An diesem Punkt fängt es an, wirk damit der Charly – für das Höhenbergsteigen hat, kann lich spannend zu werden. Rund 1200 Wetterballone gibt es man seinem EMailWechsel mit dem Italiener Simone weltweit, 40.000 Messstationen, nicht zu vergessen die Sa Moro entnehmen, der am 3.