1 Inconsistencies in Census Data: the Case of Kenya's North Eastern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mandera County Hiv and Aids Strategic Plan 2016-2019

MANDERA COUNTY HIV AND AIDS STRATEGIC PLAN 2016-2019 “A healthy and productive population” i MANDERA COUNTY HIV AND AIDS STRATEGIC PLAN 2016-2019 “A healthy and productive population” Any part of this document may be freely reviewed, quoted, reproduced or translated in full or in part, provided the source is acknowledged. It may not be sold or used for commercial purposes or for profit. iv MANDERA COUNTY HIV & AIDS STRATEGIC PLAN (2016- 2019) Table of Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations vii Foreword viii Preface ix Acknowledgement x CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background Information xii 1.2 Demographic characteristics 2 1.3 Land availability and use 2 1.3 Purpose of the HIV Plan 1.4 Process of developing the HIV and AIDS Strategic Plan 1.5 Guiding principles CHAPTER TWO: HIV STATUS IN THE COUNTY 2.1 County HIV Profiles 5 2.2 Priority population 6 2.3 Gaps and challenges analysis 6 CHAPTER THREE: PURPOSE OF Mcasp, strateGIC PLAN DEVELOPMENT process AND THE GUIDING PRINCIPLES 8 3.1 Purpose of the HIV Plan 9 3.2 Process of developing the HIV and AIDS Strategic Plan 9 3.3 Guiding principles 9 CHAPTER FOUR: VISION, GOALS, OBJECTIVES AND STRATEGIC DIRECTIONS 10 4.1 The vision, goals and objectives of the county 11 4.2 Strategic directions 12 4.2.1 Strategic direction 1: Reducing new HIV infection 12 4.2.2 Strategic direction 2: Improving health outcomes and wellness of people living with HIV and AIDS 14 4.2.3 Strategic Direction 3: Using human rights based approach1 to facilitate access to services 16 4.2.4 Strategic direction 4: Strengthening Integration of community and health systems 18 4.2.5 Strategic Direction 5: Strengthen Research innovation and information management to meet the Mandera County HIV Strategy goals. -

KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS Kenya Population Situation Analysis

REPUBLIC OF KENYA KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS Kenya Population Situation Analysis Published by the Government of Kenya supported by United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Kenya Country Oce National Council for Population and Development (NCPD) P.O. Box 48994 – 00100, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254-20-271-1600/01 Fax: +254-20-271-6058 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ncpd-ke.org United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Kenya Country Oce P.O. Box 30218 – 00100, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254-20-76244023/01/04 Fax: +254-20-7624422 Website: http://kenya.unfpa.org © NCPD July 2013 The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the contributors. Any part of this document may be freely reviewed, quoted, reproduced or translated in full or in part, provided the source is acknowledged. It may not be sold or used inconjunction with commercial purposes or for prot. KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS JULY 2013 KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS i ii KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................iv FOREWORD ..........................................................................................................................................ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ..........................................................................................................................x EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................xi -

Usaid Kenya Niwajibu Wetu (Niwetu) Fy 2018 Q3 Progress Report

USAID KENYA NIWAJIBU WETU (NIWETU) FY 2018 Q3 PROGRESS REPORT JULY 2018 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by DAI Global, LLC. USAID/KENYA NIWAJIBU WETU (NIWETU) PROGRESS REPORT FOR Q3 FY 2018 1 USAID KENYA NIWAJIBU WETU (NIWETU) FY 2018 Q3 PROGRESS REPORT 1 April – 30 June 2018 Award No: AID-OAA-I-13-00013/AID-615-TO-16-00010 Prepared for John Langlois United States Agency for International Development/Kenya C/O American Embassy United Nations Avenue, Gigiri P.O. Box 629, Village Market 00621 Nairobi, Kenya Prepared by DAI Global, LLC 4th Floor, Mara 2 Building Eldama Park Nairobi, Kenya DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. USAID/KENYA NIWAJIBU WETU (NIWETU) PROGRESS REPORT FOR Q3 FY 2018 2 CONTENTS I. NIWETU EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................... vii II. KEY ACHIEVEMENTS (Qualitative Impact) ................................................................ 9 III. ACTIVITY PROGRESS (Quantitative Impact) .......................................................... 20 III. ACTIVITY PROGRESS (QUANTITATIVE IMPACT) ............................................... 20 IV. CONSTRAINTS AND OPPORTUNITIES ................................................................. 39 V. PERFORMANCE MONITORING ............................................................................... -

Marsabit County Disease Surveillance and Response

ACCESS TO TREATMENT FOR NEGLECTED DISEASES – Experiences In Marsabit County Presented by: Abduba Liban CDSC, Marsabit County 0n 9th February 2016 at the ASTMH Conference OUTLINE 1. Brief county profile 2. Status of kala-azar marsabit county 3. Diagnosis and Treatment of Kala azar in Marsabit 4. Challenges of Accessing Treatment 5. Addressing the challenges at County Level 6. Way forward Marsabit County County Profile County Population • Visceral leishmaniasis VL (Kala azar) . Kala azar a systemic parasitic disease . It is transmitted through infected female sand fly. There are three forms of leishmaniasis; Visceral leishmanaisis (VL), Cutaneous, Muco-cutaneous . There are three endemic foci in kenya o Northwest Kenya - West Pokot, Baringo and Turkana o Eastern Province - Machakos, Kitui, Mwingi and kyuso o North-eastern Province - along the Somali border Visceral Leishmaniasis in Marsabit . VL is the common form leishmania in Marsabit . VL is a new problem in Marsabit county . There is only one treatment centre for kala azar in Marsabit – Marsabit Hospital . Distance from the furthest endemic region to the centre is 500km Kala-azar Cases by Months Kala-azar Cases by Locations Diagnosis & Treatment of Kala-azar in Marsabit Diagnosis and treatment is based on the Kenyan VL guidelines Diagnosis . A patient should be suspected in a patient from, or visiting, an endemic area who presents with: o Fever > 2 weeks o Splenomegaly o Weight loss o Diagnosis through rapid test kits – rK39 Diagnosis & Treatment of Kala-azar in Marsabit Diagnosis and treatment is based on the Kenyan VL guidelines Treatment If patient is found positive after all differentials are ruled out, they are: . -

Winning Hearts and Minds? Examining the Relationship Between Aid and Security in Kenya Mark Bradbury and Michael Kleinman ©2010 Feinstein International Center

A PR I L 2 0 1 0 Strengthening the humanity and dignity of people in crisis through knowledge and practice Winning Hearts and Minds? Examining the Relationship Between Aid and Security in Kenya Mark Bradbury and Michael Kleinman ©2010 Feinstein International Center. All Rights Reserved. Fair use of this copyrighted material includes its use for non-commercial educational purposes, such as teaching, scholarship, research, criticism, commentary, and news reporting. Unless otherwise noted, those who wish to reproduce text and image files from this publication for such uses may do so without the Feinstein International Center’s express permission. However, all commercial use of this material and/or reproduction that alters its meaning or intent, without the express permission of the Feinstein International Center, is prohibited. Feinstein International Center Tufts University 200 Boston Ave., Suite 4800 Medford, MA 02155 USA tel: +1 617.627.3423 fax: +1 617.627.3428 fic.tufts.edu Acknowledgements The report has been written by Mark Bradbury and Michael Kleinman, who take responsibility for its contents and conclusions. We wish to thank our co-researchers Halima Shuria, Hussein A. Mahmoud, and Amina Soud for their substantive contribution to the research process. Andrew Catley, Lynn Carter, and Jan Bachmann provided insightful comments on a draft of the report. Dawn Stallard’s editorial skills made the report more readable. For reasons of confidentiality, the names of some individuals interviewed during the course of the research have been withheld. We wish to acknowledge and thank all of those who gave their time to be interviewed for the study. -

County Name County Code Location

COUNTY NAME COUNTY CODE LOCATION MOMBASA COUNTY 001 BANDARI COLLEGE KWALE COUNTY 002 KENYA SCHOOL OF GOVERNMENT MATUGA KILIFI COUNTY 003 PWANI UNIVERSITY TANA RIVER COUNTY 004 MAU MAU MEMORIAL HIGH SCHOOL LAMU COUNTY 005 LAMU FORT HALL TAITA TAVETA 006 TAITA ACADEMY GARISSA COUNTY 007 KENYA NATIONAL LIBRARY WAJIR COUNTY 008 RED CROSS HALL MANDERA COUNTY 009 MANDERA ARIDLANDS MARSABIT COUNTY 010 ST. STEPHENS TRAINING CENTRE ISIOLO COUNTY 011 CATHOLIC MISSION HALL, ISIOLO MERU COUNTY 012 MERU SCHOOL THARAKA-NITHI 013 CHIAKARIGA GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL EMBU COUNTY 014 KANGARU GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL KITUI COUNTY 015 MULTIPURPOSE HALL KITUI MACHAKOS COUNTY 016 MACHAKOS TEACHERS TRAINING COLLEGE MAKUENI COUNTY 017 WOTE TECHNICAL TRAINING INSTITUTE NYANDARUA COUNTY 018 ACK CHURCH HALL, OL KALAU TOWN NYERI COUNTY 019 NYERI PRIMARY SCHOOL KIRINYAGA COUNTY 020 ST.MICHAEL GIRLS BOARDING MURANGA COUNTY 021 MURANG'A UNIVERSITY COLLEGE KIAMBU COUNTY 022 KIAMBU INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY TURKANA COUNTY 023 LODWAR YOUTH POLYTECHNIC WEST POKOT COUNTY 024 MTELO HALL KAPENGURIA SAMBURU COUNTY 025 ALLAMANO HALL PASTORAL CENTRE, MARALAL TRANSZOIA COUNTY 026 KITALE MUSEUM UASIN GISHU 027 ELDORET POLYTECHNIC ELGEYO MARAKWET 028 IEBC CONSTITUENCY OFFICE - ITEN NANDI COUNTY 029 KAPSABET BOYS HIGH SCHOOL BARINGO COUNTY 030 KENYA SCHOOL OF GOVERNMENT, KABARNET LAIKIPIA COUNTY 031 NANYUKI HIGH SCHOOL NAKURU COUNTY 032 NAKURU HIGH SCHOOL NAROK COUNTY 033 MAASAI MARA UNIVERSITY KAJIADO COUNTY 034 MASAI TECHNICAL TRAINING INSTITUTE KERICHO COUNTY 035 KERICHO TEA SEC. SCHOOL -

North Eastern - Wagalla Massacre (Nairobi) - RTJRC14.06 (NHIF Auditorium) (Benson Kaaria Testimony)

Seattle University School of Law Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons The Truth, Justice and Reconciliation I. Core TJRC Related Documents Commission of Kenya 6-14-2011 Public Hearing Transcripts - North Eastern - Wagalla Massacre (Nairobi) - RTJRC14.06 (NHIF Auditorium) (Benson Kaaria Testimony) Truth, Justice, and Reconciliation Commission Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/tjrc-core Recommended Citation Truth, Justice, and Reconciliation Commission, "Public Hearing Transcripts - North Eastern - Wagalla Massacre (Nairobi) - RTJRC14.06 (NHIF Auditorium) (Benson Kaaria Testimony)" (2011). I. Core TJRC Related Documents. 78. https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/tjrc-core/78 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the The Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission of Kenya at Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in I. Core TJRC Related Documents by an authorized administrator of Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ORAL SUBMISSIONS MADE TO THE TRUTH, JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION ON TUESDAY, 14 TH JUNE, 2011 AT THE NHIF AUDITORIUM, NAIROBI PRESENT Tecla Namachanja Wanjala - The Acting Chair, Kenya Gertrude Chawatama - Commissioner, Zambia Berhanu Dinka - Commissioner, Ethiopia Ahmed Sheikh Farah - Commissioner, Kenya Tom Ojienda - Commissioner, Kenya Margret Wambui Shava - Commissioner, Kenya Ronald Slye - Commissioner, USA (The Commission commenced at 10.00 a.m.) (The Acting Chair (Ms. Namachanja) introduced herself and the other TJRC Commissioners) (Opening Prayers) The Acting Chair (Ms. Namachanja): Hearing Clerk, could we have the witness in? Welcome to today’s hearing of the Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission, today being the 14 th day of June, 2011. -

FSNWG Presentation

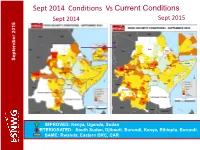

Sept 2014 Conditions Vs Current Conditions Sept 2015 Sept 2014 September 2015 September September September 2015 IMPROVED: Kenya, Uganda, Sudan DETERIORATED: South Sudan, Djibouti, Burundi, Kenya, Ethiopia, Burundi. SAME: Rwanda, Eastern DRC, CAR Current Conditions: Regional Highlights • Crisis and emergency food insecurity remains a concern in parts of DRC, CAR, South Sudan, Ethiopia, Kenya, parts of Karamoja, Darfur in Sudan, IDP sites in Somalia; September 2015 September • An estimated 17.9 people may be facing food insecurity in the region. • Dry conditions in pastoral areas of Ethiopia, Djibouti and Sudan are expected to continue till Dec (GHACOF, Aug.). • Conflicts/political tension remains a key driver for food insecurity in the region (e.g South Sudan, Burundi, CAR, eastern DRC and Somalia. • El Nino expected to lead to above average rainfall in some areas leading to improved food security outcomes but also localised flooding but depressed rainfalls in others persisting stressed/ food insecurity conditions General improvement in food security situation in the region. However, some deterioration seen in pastoral areas and an estimated 17.9M people in need of humanitarian assistance. Current Conditions – Burundi Burundi WFP, IPC (priliminary) •Generally food security conditions is good due to the season B harvest. September 2015 September •About 100,000 are considered in food insecurity crisis. •Significant number of farming population have fled to neigboring countries (UNHCR) due to the political crisis •The political crisis negatively affected Economic Activities in the country, particularly the capital Bujumbura. Trade in agricultural comoditities fell by about 50%. •The lean period is expected to start in September, is likely be exacerbated by the negative effects of the current crisis Food security relatively stable due to Season B production though expected to remain stressed to December. -

Abstracts 2019 July Graduation

ABSTRACTS 2019 JULY GRADUATION PHD SCHOOL OF BUSINESS FINANCING DECISIONS AND SHAREHOLDER VALUE CREATIONOF NON- FINANCIAL FIRMS QUOTED AT THE NAIROBI SECURITIES EXCHANGE, KENYA KARIUKI G MUTHONI-PHD Department: Business Administration Supervisors: Dr. Ambrose O. Jagongo Dr. Joseph Muniu Shareholder value creation and profit maximizing are among the primary objectives of a firm. Shareholder value creation focuses more on long term sustainability of returns and not just profitability. Rational investors expect good long term yield of their investment. Corporate financial decisions play an imperative role in general performance of a company and shareholder value creation. There have been a number of firms facing financial crisis among them; Mumias Sugar Ltd, Uchumi Supermarkets Ltd and Kenya Airways Ltd. All these companies are quoted at the Nairobi Securities Exchange. Due to declining performance of these companies, share prices have been dropping and shareholders do not receive dividends. This study investigated the effects of financing decisions on shareholder value creation of non- financial firms quoted at NSE for the period 2008-2014. The study was guided by various finance models; which include, Modigliani and Miller, Pecking Order Theory, Agency Free Flow Theory, Market Timing Theory and Capital Asset Pricing Model. The study used general and empirical models from previous studies as a basis for studying specific models which were modified to suit the current study. The study was guided by the positivism philosophy. The study employed explanatory design which is non-experimental. Census design was used as the number of non- financial firms at the time of the study was 40 companies. The data was gathered from NSE handbooks and CMA publications comprising of annual financial statements, income statements and accompanying notes. -

INSULT to INJURY the 2014 Lamu and Tana River Attacks and Kenya’S Abusive Response

INSULT TO INJURY The 2014 Lamu and Tana River Attacks and Kenya’s Abusive Response HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH hrw.org www.khrc.or.ke Insult to Injury The 2014 Lamu and Tana River Attacks and Kenya’s Abusive Response Copyright © 2015 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-32446 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JUNE 2015 978-1-6231-32446 Insult to Injury The 2014 Lamu and Tana River Attacks and Kenya’s Abusive Response Map of Kenya and Coast Region ........................................................................................ i Summary ......................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations .......................................................................................................... -

Violent Extremism and Clan Dynamics in Kenya

[PEACEW RKS [ VIOLENT EXTREMISM AND CLAN DYNAMICS IN KENYA Ngala Chome ABOUT THE REPORT This report, which is derived from interviews across three Kenyan counties, explores the relationships between resilience and risk to clan violence and to violent extrem- ism in the northeast region of the country. The research was funded by a grant from the United States Agency for International Development through the United States Institute of Peace (USIP), which collaborated with Sahan Africa in conducting the study. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Ngala Chome is a former researcher at Sahan Research, where he led a number of countering violent extremism research projects over the past year. Chome has published articles in Critical African Studies, Journal of Eastern Afri- can Studies, and Afrique Contemporine. He is currently a doctoral researcher in African history at Durham University. The author would like to thank Abdulrahman Abdullahi for his excellent research assistance, Andiah Kisia and Lauren Van Metre for helping frame the analysis, the internal reviewers, and two external reviewers for their useful and helpful comments. The author bears responsibility for the final analysis and conclusion. Cover photo: University students join a demonstration condemning the gunmen attack at the Garissa University campus in the Kenyan coastal port city of Mombasa on April 8, 2015. (REUTERS/Joseph Okanga/ IMAGE ID: RTR4WI4K) The views expressed in this report are those of the author alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Institute of Peace. United States Institute of Peace 2301 Constitution Ave., NW Washington, DC 20037 Phone: 202.457.1700 Fax: 202.429.6063 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.usip.org Peaceworks No. -

Arboviruses of Human Health Significance in Kenya Atoni E1,2

Arboviruses of Human Health significance in Kenya Atoni E1,2#, Waruhiu C1,2#, Nganga S1,2, Xia H1, Yuan Z1 1. Key Laboratory of Special Pathogens, Wuhan Institute of Virology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan 430071, China 2. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, 100049, China #Authors contributed equally to this work Correspondence: Zhiming Yuan, [email protected]; Tel.: +86-2787198195 Summary In tropical and developing countries, arboviruses cause emerging and reemerging infectious diseases. The East African region has experienced several outbreaks of Rift valley fever virus, Dengue virus, Chikungunya virus and Yellow fever virus. In Kenya, data from serological studies and mosquito isolation studies have shown a wide distribution of arboviruses throughout the country, implying the potential risk of these viruses to local public health. However, current estimates on circulating arboviruses in the country are largely underestimated due to lack of continuous and reliable countrywide surveillance and reporting systems on arboviruses and disease vectors and the lack of proper clinical screening methods and modern facilities. In this review, we discuss arboviruses of human health importance in Kenya by outlining the arboviruses that have caused outbreaks in the country, alongside those that have only been detected from various serological studies performed. Based on our analysis, at the end we provide workable technical and policy-wise recommendations for management of arboviruses and arboviral vectors in Kenya. [Afr J Health Sci. 2018; 31(1):121-141] and mortality. Recently, the outbreak of Zika virus Introduction became a global public security event, due to its Arthropod-borne viruses (Arboviruses) are a cause ability to cause congenital brain abnormalities, of significant human and animal diseases worldwide.