Alliance in Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Israel's National Religious and the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict

Leap of Faith: Israel’s National Religious and the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict Middle East Report N°147 | 21 November 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iv I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Religious Zionism: From Ascendance to Fragmentation ................................................ 5 A. 1973: A Turning Point ................................................................................................ 5 B. 1980s and 1990s: Polarisation ................................................................................... 7 C. The Gaza Disengagement and its Aftermath ............................................................. 11 III. Settling the Land .............................................................................................................. 14 A. Bargaining with the State: The Kookists ................................................................... 15 B. Defying the State: The Hilltop Youth ........................................................................ 17 IV. From the Hills to the State .............................................................................................. -

Israel and Overseas: Israeli Election Primer 2015 (As Of, January 27, 2015) Elections • in Israel, Elections for the Knesset A

Israel and Overseas: Israeli Election Primer 2015 (As of, January 27, 2015) Elections In Israel, elections for the Knesset are held at least every four years. As is frequently the case, the outgoing government coalition collapsed due to disagreements between the parties. As a result, the Knesset fell significantly short of seeing out its full four year term. Knesset elections in Israel will now be held on March 17, 2015, slightly over two years since the last time that this occurred. The Basics of the Israeli Electoral System All Israeli citizens above the age of 18 and currently in the country are eligible to vote. Voters simply select one political party. Votes are tallied and each party is then basically awarded the same percentage of Knesset seats as the percentage of votes that it received. So a party that wins 10% of total votes, receives 10% of the seats in the Knesset (In other words, they would win 12, out of a total of 120 seats). To discourage small parties, the law was recently amended and now the votes of any party that does not win at least 3.25% of the total (probably around 130,000 votes) are completely discarded and that party will not receive any seats. (Until recently, the “electoral threshold,” as it is known, was only 2%). For the upcoming elections, by January 29, each party must submit a numbered list of its candidates, which cannot later be altered. So a party that receives 10 seats will send to the Knesset the top 10 people listed on its pre-submitted list. -

Security Council Distr.: General 10 August 2018

United Nations S/2018/584 Security Council Distr.: General 10 August 2018 Original: English Identical letters dated 9 August 2018 from the Permanent Representative of Israel to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council I write to inform you of the Hamas terrorist organization’s current attack against Israel. Yesterday afternoon, Hamas snipers fired at Israeli civilians engaged in the construction of the barrier along the security fence. In response, the Israel Defense Forces targeted the Hamas outpost. Hamas then escalated its attack by firing at least 180 rockets towards civilian communities in Israel, including the major population centre of Be’er Sheva‘, injuring at least 15 people. The towns surrounding the Gaza Strip have endured ongoing “red alert” sirens for imminent rocket attacks. In addition to these attacks, which have caused damage to factories and homes, Hamas rockets have also fallen on playgrounds, with children in close proximity. In response to this unacceptable onslaught of violent attacks, the Israel Defense Forces have targeted Hamas terror sites in the Gaza Strip, including military compounds, among them rocket manufacturing facilities and a central logistical military complex. The Israel Defense Forces have also targeted an offensive terror tunnel shaft, two Hamas combat tunnels and a factory for terror tunnel parts. Hamas is solely responsible for this assault. The terrorist organization has, once again, deprived the children of southern Israel of yet another summer. Israel will continue to take all necessary steps to prevent civilian casualties and protect its sovereignty. I call upon the Security Council to condemn Hamas in the strongest terms for its indiscriminate attacks against innocent civilian populations, and to finally designate Hamas as a terrorist organization. -

S/PV.8717 the Situation in the Middle East, Including the Palestinian Question 11/02/2020

United Nations S/ PV.8717 Security Council Provisional Seventy-fifth year 8717th meeting Tuesday, 11 February 2020, 10 a.m. New York President: Mr. Goffin ..................................... (Belgium) Members: China ......................................... Mr. Zhang Jun Dominican Republic ............................. Mr. Singer Weisinger Estonia ........................................ Mr. Jürgenson France ........................................ Mr. De Rivière Germany ...................................... Mr. Schulz Indonesia. Mr. Djani Niger ......................................... Mr. Aougi Russian Federation ............................... Mr. Nebenzia Saint Vincent and the Grenadines ................... Ms. King South Africa ................................... Mr. Mabhongo Tunisia ........................................ Mr. Ladeb United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland .. Ms. Pierce United States of America .......................... Mrs. Craft Viet Nam ...................................... Mr. Dang Agenda The situation in the Middle East, including the Palestinian question This record contains the text of speeches delivered in English and of the translation of speeches delivered in other languages. The final text will be printed in the Official Records of the Security Council. Corrections should be submitted to the original languages only. They should be incorporated in a copy of the record and sent under the signature of a member of the delegation concerned to the Chief of the Verbatim Reporting Service, room -

IATF Fact Sheet: Religion

1 FACT SHEET iataskforce.org Topic: Religion – Druze Updated: June 2014 The Druze community in Israel consists of Arabic speakers from an 11th Century off-shoot of Ismaili Shiite theology. The religion is considered heretical by orthodox Islam.2 Members of the Druze community predominantly reside in mountainous areas in Israel, Lebanon, and Syria.3 At the end of 2011, the Druze population in Israel numbered 133,000 inhabitants and constituted 8.0% of the Arab and Druze population, or 1.7%of the total population in Israel.4 The Druze population resides in 19 localities located in the Northern District (81% of the Druze population, excluding the Golan Heights) and Haifa District (19%). There are seven localities which are exclusively Druze: Yanuh-Jat, Sajur, Beit Jann, Majdal Shams, Buq’ata, Mas'ade, and Julis.5 In eight other localities, Druze constitute an overwhelming majority of more than 75% of the population: Yarka, Ein al-Assad, Ein Qiniyye, Daliyat al-Karmel, Hurfeish, Kisra-Samia, Peki’in and Isfiya. In the village of Maghar, Druze constitute an almost 60% majority. Finally, in three localities, Druze account for less than a third of the population: Rama, Abu Snan and Shfar'am.6 The Druze in Israel were officially recognized in 1957 by the government as a distinct ethnic group and an autonomous religious community, independent of Muslim religious courts. They have their own religious courts, with jurisdiction in matters of personal status and spiritual leadership, headed by Sheikh Muwaffak Tarif. 1 Compiled by Prof. Elie Rekhess, Associate Director, Crown Center for Jewish and Israel Studies, Northwestern University 2 Naim Araidi, The Druze in Israel, Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, December 22, 2002, http://www.mfa.gov.il; Gabriel Ben Dor, “The Druze Minority in Israel in the mid-1990s”, Jerusalem Letters, 315, June 1, 1995, JerusalemCenter for Public Affairs. -

Just Below the Surface: Israel, the Arab Gulf States and the Limits of Cooperation

Middle East Centre JUST BELOW THE SURFACE ISRAEL, THE ARAB GULF STATES AND THE LIMITS OF COOPERATION IAN BLACK LSE Middle East Centre Report | March 2019 About the Middle East Centre The Middle East Centre builds on LSE’s long engagement with the Middle East and provides a central hub for the wide range of research on the region carried out at LSE. The Middle East Centre aims to enhance understanding and develop rigorous research on the societies, economies, polities and international relations of the region. The Centre promotes both special- ised knowledge and public understanding of this crucial area, and has outstanding strengths in interdisciplinary research and in regional expertise. As one of the world’s leading social science institutions, LSE comprises departments covering all branches of the social sciences. The Middle East Centre harnesses this expertise to promote innova- tive research and training on the region. Middle East Centre Just Below the Surface: Israel, the Arab Gulf States and the Limits of Cooperation Ian Black LSE Middle East Centre Report March 2019 About the Author Ian Black is a former Middle East editor, diplomatic editor and European editor for the Guardian newspaper. He is currently Visiting Senior Fellow at the LSE Middle East Centre. His latest book is entitled Enemies and Neighbours: Arabs and Jews in Palestine and Israel, 1917–2017. Abstract For over a decade Israel has been strengthening links with Arab Gulf states with which it has no diplomatic relations. Evidence of a convergence of Israel’s stra- tegic views with those of Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Bahrain has accumulated as all displayed hostility to Iran’s regional ambitions and to United States President Barack Obama’s policies during the Arab Spring. -

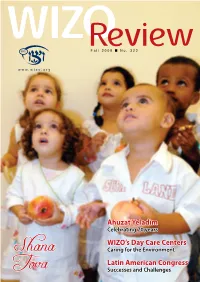

Fall 2009 No

Fall 2009 No. 322 Ahuzat Yeladim Celebrating 70 years WIZO’s Day Care Centers Shana Caring for the Environment Latin American Congress Tova Successes and Challenges Women’s International Zionist Organization for an Improved Israeli Society You Are WIZO’s Future… Let’s Get Together! WIZO Aviv International Seminar November 15 – 19, 2009, Tel Aviv, Israel Come join young WIZO members from 50 federations worldwide! Participate in workshops on: Membership Recruitment, Organization, and Fundraising Hear top-level speakers on: Israel Today Women’s Leadership Jewish Education Visit WIZO Projects Tour Jerusalem Leadership Training For young WIZO members up to age 45 YOU BRING A SUITCASE - WE’LL PROVIDE THE REST For further information and registration, contact the head office of your local WIZO Federation subject Editor: Ingrid Rockberger Fall 2009 No. 322 www.wizo.org Assistant Editor: Tricia Schwitzer Editorial Board: Helena Glaser, Tova Ben Dov, Yochy Feller, Zipi Amiri, Esther Mor, Sylvie Pelossof, Briana Simon Rebecca Sieff WIZO Center, Graphic Design: StudioMooza.com 38 David Hamelech Blvd., Photos: Lilach Bar Zion, Allon Borkovski, Israel Sun, Tel Aviv, Israel Sharna Kingsley, Mydas Photography, John Rifkin, Tel: 03-6923805 Fax: 03-6923801 Ingrid Rockberger, Ulrike Schuettler, Yuval Tebol Internet: www.wizo.org Published by World WIZO Publicity and E-mail: [email protected] Communications Department Cover photo: Children in WIZO’s Bruce and Ruth Rappaport reinforced day care center in Sderot celebrate the New Year. Contents 04 President’s -

A Discussion with Ambassador Danny Danon

Hudson Institute Priorities of Israel's National Unity Government: A Discussion with Ambassador Danny Danon TRANSCRIPT Discussion……………………………………………….………….……..………….…………...……2 • Danny Danon, Israeli Ambassador to the United States • Michael Doran, Senior Fellow, Hudson Institute About Hudson Institute: Founded in 1961 by strategist Herman Kahn, Hudson Institute challenges conventional thinking and helps manage strategic transitions to the future through interdisciplinary studies in defense, international relations, economics, health care, technology, culture, and law. Hudson seeks to guide public policy makers and global leaders in government and business through a vigorous program of publications, conferences, policy briefings, and recommendations. Please note: This transcript is based off a recording and mistranslations may appear in text. A video of the event is available: https://www.hudson.org/events/1795-video-livestream-priorities- of-israel-s-national-unity-government-a-discussion-with-ambassador-danny-danon42020 Hudson Institute | 1201 Pennsylvania Ave NW, Fourth Floor, Washington DC 20004 A Discussion with Ambassador Danny Danon | April 6, 2020 Michael Doran: Good afternoon everyone. My name is Mike Doran and I'm a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute, broadcasting to you live from a secure undisclosed location in Washington DC and we are honored here today to be hosting a conversation with Israel's ambassador to the United Nations, Danny Danon. The ambassador is not a career diplomat. He has a history, his background is in Israeli politics. He was a member of the Knesset for six years from 2009 to '15. After that, he served as the Deputy Minister of Defense from 2013 to '14. And then after that he was the Minister of Science, Technology, and Space in the Israeli government. -

Benfredj Esther 2011 Mémoire.Pdf (1.581Mo)

Université de Montréal Les affrontements idéologiques nationalistes et stratégiques au Proche-Orient vus à travers le prisme de la Société des Nations et de l’Organisation des Nations Unies par Esther Benfredj Faculté de droit Mémoire présenté à la Faculté de droit en vue de l’obtention du grade de LL.M en droit option droit international décembre 2011 ©Esther Benfredj, 2011 Université de Montréal Faculté des études supérieures et postdoctorales Ce mémoire intitulé : Les affrontements idéologiques nationalistes et stratégiques au Proche-Orient vus à travers le prisme de la Société des Nations et de l’Organisation des Nations Unies présenté par : Esther Benfredj évalué par un jury composé des personnes suivantes : Michel Morin Président-rapporteur Isabelle Duplessis Directrice de recherche Jean-François Gaudreault-Desbiens Membre du jury i Résumé L’effondrement et le démantèlement de l’Empire ottoman à la suite de la Première Guerre mondiale ont conduit les Grandes puissances européennes à opérer un partage territorial du Proche-Orient, légitimé par le système des mandats de la Société des Nations (SDN). Sans précédent, cette administration internationale marqua le point de départ de l’internationalisation de la question de la Palestine, dont le droit international allait servir de socle à une nouvelle forme de colonialisme. Au lendemain de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, l’Organisation des Nations Unies (ONU) continua l’action entreprise par la SDN en s’occupant également de cette question sur la demande des Britanniques. En novembre 1947, l’ONU décida du partage de la Palestine en deux Etats pour résoudre les conflits entre sionistes et nationalistes arabes. -

ACTION ~Et~Cr Copytqs ~R. C

AMBASSADOR DANNY DANON Pl1 'l1 1'1~\!>il PERMANENT REPRESENTATIVE OF ISRAEL V1Jj7i1 ~'~li1 TO THE UNITED NATIONS nnmNnil mmN7 7N1'1!>' 7'1!> r- · ,~·- ---~·------1 H.E. Mr. Ban Ki-moon ACTION ~et~c-r JUL - 7 2016 - o ({)t>" 1 Secretary-General COPYtQs~r. ctAL l b United Nations ~ kn·=·!• _._ _________ _J 5July20I6 Excellency, I am writing once again to inform you of the dangerous and destabilizing behavior of Iran and of its continuous support and funding of its proxy Hezbollah. A decade has passed since the Security Council adopted Resolution I70 I. And yet, Hezbollah, an internationally recognized terror group, continues its military buildup in violation of the aforementioned resolution. These flagrant violations are supported and funded by Iran, Hezbollah' s main benefactor. The evidence of these violations is mounting each day. While in the past Hezbollah made an effort to hide its illegal activities, today they're openly declared and are overwhelmingly apparent. On June 24, Hassan Nasrallah, the Secretary General of Hezbollah, admitted in an interview that: "Hezbollah's budget and its expenses are coming from the Islamic Republic of Iran ... Our allocated money is coming to us in the same way we receive our rockets with which we threaten Israel." Just a week after this statement, Brigadier General Hossein Salami, the second-in command of the Islamic Revolution Guards Corps (IRGC) boasted: "Today, only in Lebanon, more than I 00,000 Qaem missiles are ready for launch ... these missiles would come down on the heart of the Zionist regime and be the prelude for a big collapse in the modem era". -

Israel: Political Development and Data for 2017

European Journal of Political Research Political Data Yearbook 0: 1–8, 2018 1 doi: 10.1111/2047-8852.12214 Israel: Political development and data for 2017 EMMANUEL NAVON1 & ABRAHAM DISKIN2 1Tel-Aviv University and Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya, Israel; 2The Academic Center of Science and Law, Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel Introduction In 2017, the Israeli governing majority was partially split by issues of state and religion, and it was overshadowed by police investigations over corruption charges involving the Prime Minister and his entourage. Yet the coalition remained stable and unchallenged. The opposition was temporarily reinvigorated by the election of a new leader for the Labor Party, but polls continued to show a widespread support for the Likud-led coalition. While Israel continued to experience ‘lone-wolf’ terrorist attacks, its international standing improved dramatically with the election in the United States of Donald Trump and thanks to a proactive foreign policy which produced significant achievements. The Israeli economy continued to grow with healthy macroeconomic parameters. Election report There were no elections in 2017. The present Knesset was elected in March 2015 and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Defense Minister Avigdor Lieberman have both predicted that the present government will serve its full term – an optimistic estimation given the fact that no legislature in Israel has served its full term since 1988 (Israel Central Elections Committee n.d.). Cabinet report While there were no changes in the composition of the government, the political standing of Prime Minister Netanyahu was overshadowed by police investigations involving him and his entourage. In January began a series of police interrogations of the Prime Minister over two separate cases. -

Netanyahu Faces Test of Party Strength Ahead of Israeli Election

Netanyahu Faces Test of Party Strength Ahead of Israeli Election By Calev Ben-David Dec 31, 2014 12:00 AM GMT+0200 Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s Likud party is selecting its March 17 parliamentary election ticket in a race that may shape peacemaking with the Palestinians. While Netanyahu’s leadership of the party doesn’t seem to be at risk in today’s contest, his sole opponent, lawmaker Danny Danon, represents a more hard-line faction within Likud that opposes Palestinian statehood and is vying to seat more candidates in parliament. With polls favoring Netanyahu to form the next government, the ticket’s ideological bent will have implications that go beyond party politics. “It’s a foregone conclusion that Netanyahu will win” the Likud race, Yehuda Ben Meir, senior fellow at Tel Aviv’s Institute for National Security Studies, said in a phone interview yesterday. If hard-liners dominate the party ticket in the parliamentary contest, though, “Netanyahu will not be able to move on peacemaking with the Palestinians, and will basically become a prisoner in his own house,” he said. The last round of U.S.-led peace talks collapsed in April. U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry, who led the negotiations, has voiced interest in resuming them. Netanyahu called early elections Dec. 2 after clashing with members of his governing coalition over issues including peacemaking. Under Israel’s parliamentary system, voters cast ballots for slates and don’t elect their legislators directly. Likud chooses its list through a primary election. About 96,600 Likud members are eligible to choose among 70 candidates to represent the party in the March race.