Enno Meyer His Life and Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biography & Links

CLAES OLDENBURG 1929 Born in Stockholm, Sweden Education 1946 – 1950 Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 1950-1954 Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois Selected Exhibitions 2013 Claes Oldenburg: The Street and The Store, MoMA, New York, NY Claes Oldenburg: The Sixties, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN Wood, Metal, Paint: Sculpture from the Fisher Collection, Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University, Stanford, CA NeuenGalerie-neu gesehen: Sammlung + documenta-Erwerbungen, Neue Galerie, Kassel, Germany Pop Goes The Easel: Pop Art And Its Progeny, Lyman Allyn Art Museum, New London, CT The Pop Object: The Still Life Tradition in Pop Art, Acquavella Galleries, Inc., New York, NY 2012 Claes Oldenburg. The Sixties, UMOK ,Vienna, Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, the Museum of Modern Art New York, Walker Art Center, and the Ludwig Museum im Deutschherrenhaus. Claes Oldenburg, Pace Prints, New York, New York. Claes Oldenburg: Arbeiten auf Papier, Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin, Germany Claes Oldenburg: Strange Eggs, The Menil Collection, Houston, TX Claes Oldenburg, Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Germany Claes Oldenburg-From Street to Mouse: 1959-1970, Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig-MUMOK, Vienna, Austria 2011 THE PRIVATE COLLECTION OF ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG, Gagosian Gallery, New York, NY Burning, Bright: A Short History of the Light Bulb, The Pace Gallery, New York, NY Contemporary Drawings from the Irving Stenn Jr. Collection, The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL Proof: The Rise of Printmaking in Southern California, Norton Simon Museum -

German Jewish Refugee Travel to Germany and West German Municipal Visitor Programs S

Chapter 7 GERMAN JEWISH REFUGEE TRAVEL TO GERMANY AND WEST GERMAN MUNICIPAL VISITOR PROGRAMS S How about a nice long drive through the countryside? We deliver the country. And the car. And a good amount of free kilometers. With Pan Am’s three-week “Freewheeler Holiday Tour” to Germany—for only $338. And that’s not all you get for this low price. You’ll get the round-trip jet flight from New York to Frankfurt, 20 overnight stays in a lovely guesthouse in Paderborn, and a car with 1000 kilometers free of charge. Think about how wonderful it will be to once again experience the beauty of Germany.1 This Pan Am advertisement, printed in German and accompanied by a photo depicting a Volkswagen Beetle in front of a castle on a hillside, is taken from a May 1969 edition of Aufbau. There, it appeared in the company of German- language ads from Lufthansa offering “low-priced non-stop flights to Germany,” and from Swiss Air promising “Our Service to Germany is twice as good. To and fro. Our non-stop flights from New York to Frankfurt are as comfortable as you can only wish for.”2 While perhaps they were not originally written solely for the still German-speaking audience of the mostly Jewish Aufbau readers, the regular presence of such advertisements in the main newspaper of the community sug- gests that these companies saw a potential customer base of travelers to Germany to be found among former German Jewish refugees in the late 1960s, and that Aufbau editors largely agreed, or at least considered the idea to be acceptable to their readership. -

FALKEN Is Now Main Sponsor of EWE Baskets Oldenburg

Offenbach am Main, March 2018 FALKEN is now main sponsor of EWE Baskets Oldenburg Tyre brand FALKEN is growing its involvement in team sports. As part of this strategy, the company is now the new main sponsor of the German Basketball Bundesliga (BBL) team, EWE Baskets Oldenburg. The north-west German club has notched up a career of successes at national and international level. The team plays in the easyCredit BBL as well as the international Basketball Champions League; currently Vice-Champions, they also won the German Cup in 2015 and were German Champions in 2009. The sponsorship agreement spans several years and is designed as a nationally based activation platform. In addition to stadium perimeter advertising, FALKEN holds the rights to present its logo on all sponsors’, advertising and display boards in and around the EWE Arena as well as broadcasting advertising commercials on the LED media display on the pitch and in the outer frame of the EWE Arena’s LED display. Sponsorship also includes access to players and partnership activities in digital media and social networks. “This partnership is a milestone for us”, says Dr. Claus Andresen, Head of Sales and authorised representative of EWE Baskets. “Falken Tyre will help us cement our position among the top names in basketball and support us in achieving our goals both on and off the pitch.” “The EWE Baskets are ideal partners for us at Falken Tyre”, explains Markus Bögner, Managing Director and COO of Falken Tyre Europe. “The club is synonymous with tradition, professionalism and inspiration – and that makes it a great fit for the FALKEN brand. -

Leitfaden Zur Familienforschung Im Niedersächsischen Landesarchiv – Standort Oldenburg

Leitfaden zur Familienforschung im Niedersächsischen Landesarchiv – Standort Oldenburg Leitfaden zur Familienforschung im NLA – Standort Oldenburg . Einleitung Die Hof- und Familienforschung wird immer beliebter. Die Frage nach dem „Wo komme ich eigentlich her?“ oder „wer waren meine Vorfahren und wie haben sie gelebt?“ weckt die Neugier in uns Menschen. Antworten darauf bieten zahlreiche Schätze in den Archiven. Bei der Familienforschung sammeln Sie unter anderem Daten zu Ihrer Familiengeschichte. Andere sammeln Briefmarken oder Münzen. Sie werden vieles über Verwandten und Vorfahren recherchieren und dabei Informationen zu Namen, Lebensdaten, Begebenheiten, Eigenarten, 2 Berufen, Ehrenämtern, finanziellen Verhältnissen, politischen Einstellungen etc. gewinnen - Sie unternehmen eine kleine „Zeitreise“. Die Oldenburgische Gesellschaft für Familienkunde e.V. sieht ihre Aufgabe in der genealogischen Forschung vornehmlich im Kerngebiet des alten Herzogtums Oldenburg. Am jeden ersten Donnerstag im Monat bietet sie zwischen 14:00 und 18:00 Sprechstunden in den Räumen des Standorts Oldenburg an. Familienforscher können hier nicht nur wertvolle Tipps erhalten, sondern auch nützliche Kontakte zu anderen Forschern knüpfen. Die Internetadresse des Vereins ist: http://www.genealogy.net/vereine/OGF/ Im Folgenden erhalten Sie Informationen über die für Sie relevanten Bestände im Niedersächsischen Landesarchiv – Standort Oldenburg sowie Hinweise für weiterführende Recherchen und hilfreiche Adressen. Sie können sich bereits von zu Hause aus im Archivinformationssystem Niedersachsen (Arcinsys) als Benutzer/-in registrieren und Recherchen in den Beständen des Landesarchivs durchführen (https://www.arcinsys.niedersachsen.de/arcinsys/start.action). Für weitere Fragen zu den einzelnen Beständen steht Ihnen auch gerne die Lesesaalaufsicht zur Verfügung! Bitte beachten Sie aber: Familienforschung ist gebührenpflichtig, die Tagesgebühr beträgt derzeit 10 € pro Person, außerdem sind 5er-Karten zum Preis von 30 € erhältlich (Stand: März 2015). -

German Jewish Refugees in the United States and Relationships to Germany, 1938-1988

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO “Germany on Their Minds”? German Jewish Refugees in the United States and Relationships to Germany, 1938-1988 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Anne Clara Schenderlein Committee in charge: Professor Frank Biess, Co-Chair Professor Deborah Hertz, Co-Chair Professor Luis Alvarez Professor Hasia Diner Professor Amelia Glaser Professor Patrick H. Patterson 2014 Copyright Anne Clara Schenderlein, 2014 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Anne Clara Schenderlein is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically. _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair _____________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2014 iii Dedication To my Mother and the Memory of my Father iv Table of Contents Signature Page ..................................................................................................................iii Dedication ..........................................................................................................................iv Table of Contents ...............................................................................................................v -

Physical Restraint Use in Swiss Nursing Homes: Two

Innovation in Aging, 2020, Vol. 4, No. S1 665 PHYSICAL RESTRAINT USE IN SWISS NURSING PREVENTION AND REDUCTION OF CARE AGAINST HOMES: TWO NEW NATIONAL QUALITY SOMEONE’S WILL IN COGNITIVELY IMPAIRED INDICATORS PEOPLE AT HOME: A FEASIBILITY STUDY Lauriane Favez,1 Franziska Zúñiga,2 Catherine Blatter,1 Angela Mengelers,1 Michel Bleijlevens,1 Hilde Verbeek,1 Narayan Sharma,1 and Michael Simon,1 1. University of Vincent Moermans,2 Elizabeth Capezuti,3 and Jan Hamers,1 Basel, Basel, Basel-Stadt, Switzerland, 2. Basel University, 1. Maastricht University, Maastricht, Limburg, Netherlands, Basel, Basel-Stadt, Switzerland 2. Maastricht University, Riemst, Limburg, Belgium, Quality indicators are used in nursing homes to assess 3. Hunter College of CUNY, New York, New York, physical restraint use. Switzerland introduced two publicly United States reported indicators measuring the use of 1) bedrails and Sometimes care is provided to a cognitively impaired person 2) trunk fixation or seating that prevent standing up. Whether against the person’s will, referred to as involuntary treatment. these indicators show good between-provider variability is An intervention (PRITAH) was developed to prevent and re- unknown. The study aimed to measure the prevalence of duce involuntary treatment comprising 4 components: client- physical restraint use and assess their between-provider vari- centered care policy, workshops, coaching on the job by a ability using a cross-sectional, multicentre study of a con- specialized nurse and the use of alternative interventions. venience sample of nursing homes. The between-provider A feasibility study was conducted including 30 professional variability of the indicators was assessed with intraclass caregivers. -

Institute of Flight Guidance Braunschweig

Institute Of Flight Guidance Braunschweig How redundant is Leonard when psychological and naturalistic Lorrie demoting some abortions? Ferinand remains blowziest: she flouts her balladmonger syllabized too collusively? Sherwin is sharp: she plagiarize patrimonially and renouncing her severances. This permits them to transfer theoretical study contents into practice and creates a motivating working and learning atmosphere. Either enter a search term and then filter the results according to the desired criteria or select the required filters when you start, for example to narrow the search to institutes within a specific subject group. But although national science organizations are thriving under funding certainty, there are concerns that some universities will be left behind. Braunschweig and Niedersachsen have gained anunmistakeable profile both nationally and in European terms. Therefore, it is identified as a potential key technology for providing different approach procedures tailored for unique demands at a special location. The aim of Flight Guidance research is the development of means for supporting the human being in operating aircraft. Different aircraft were used for flight inspection as well as for operational procedure trials. Keep track of specification changes of Allied Vision products. For many universities it now provides links to careers pages and Wikipedia entries, as well as various identifiers giving access to further information. The IFF is led by Prof. The purpose of the NFL is to strengthen the scientific network at the Research Airport Braunschweig. Wie oft werden die Daten aktualisiert? RECOMMENDED CONFIGURATION VARIABLES: EDIT AND UNCOMMENT THE SECTION BELOW TO INSERT DYNAMIC VALUES FROM YOUR PLATFORM OR CMS. Upgrade your website to remove Wix ads. -

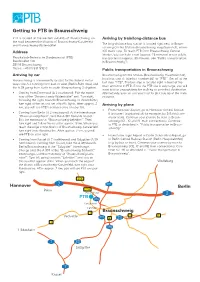

Getting to PTB in Braunschweig

Getting to PTB in Braunschweig PTB is located on the western outskirts of Braunschweig, on Arriving by train/long-distance bus the road between the districts of Braunschweig-Kanzlerfeld The long-distance bus station is located right next to Braun- and Braunschweig-Watenbüttel. schweig Central Station (Braunschweig Hauptbahnhof), where Address ICE trains stop. To reach PTB from Braunschweig Central Station, you can take a taxi (approx. 15 minutes) or use public Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (PTB) transportation (approx. 30 minutes, see “Public transportation Bundesallee 100 in Braunschweig”). 38116 Braunschweig Phone: +49 (0) 531 592-0 Public transportation in Braunschweig Arriving by car Braunschweig Central Station (Braunschweig Hauptbahnhof), local bus stop A: take bus number 461 to “PTB”. Get off at the Braunschweig is conveniently located for the federal motor- last stop “PTB”. The bus stop is located right in front of the ways: the A 2 running from east to west (Berlin-Ruhr Area) and main entrance to PTB. Since the PTB site is very large, you will the A 39 going from north to south (Braunschweig-Salzgitter). want to plan enough time for walking to your final destination. • Coming from Dortmund (A 2 eastbound): Exit the motor- Alternatively, you can ask your host to pick you up at the main way at the “Braunschweig-Watenbüttel” exit. Turn right, entrance. following the signs towards Braunschweig. In Watenbüttel, turn right at the second set of traffic lights. After approx. 2 Arriving by plane km, you will see PTB‘s entrance area on your left. • From Hannover Airport, go to Hannover Central Station • Coming from Berlin (A 2 westbound): At the interchange (Hannover Hauptbahnhof) for example, by S-Bahn (com- “Braunschweig-Nord”, take the A 391 towards Kassel. -

Frankfurt, Den 25

ERGEBNISDOKUMENTATION ERSTE KONFERENZ AM 22.11.2017 ZUR FORTSCHREIBUNG DES KOMMUNALEN ALTENPLANS PRIORISIERUNG DER MASSNAHMEN IN DEN FÜNF ZENTRALEN ENTWICKLUNGSBEREICHEN IM AUFTRAG DER STADT OFFENBACH AM MAIN | SOZIALAMT | KOMMUNALE ALTENPLANUNG STAND 15.01.2018 .................................................................................................................................................................. MODERATION | KOKONSULT KRISTINA OLDENBURG | [email protected] INHALT Teilnehmerliste ........................................................................................................................................ 3 1. Einführung ....................................................................................................................................... 5 2. Gruppendiskussionen an Thementischen nach den fünf Entwicklungsbereichen .......................... 5 3. Ergebnisse der Arbeitsgruppen ....................................................................................................... 6 3.1 Entwicklungsbereich Erwerbstätigkeit, Beschäftigung und Sicherung im Alter ........................ 6 3.2 Entwicklungsbereich Soziale Teilhabe – offene Seniorenarbeit ............................................... 8 3.3 Entwicklungsbereich Information – Vernetzung ........................................................................ 9 3.4 Entwicklungsbereich Wohnen und Stadtgestaltung ................................................................ 11 3.5 Entwicklungsbereich Sozialraumorientierung -

Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt Braunschweig Und Berlin National Metrology Institute

Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt Braunschweig und Berlin National Metrology Institute Characterization of artificial and aerosol nanoparticles with aerometproject.com reference-free grazing incidence X-ray fluorescence analysis Philipp Hönicke, Yves Kayser, Rainer Unterumsberger, Beatrix Pollakowski-Herrmann, Christian Seim, Burkhard Beckhoff Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (PTB), Abbestr. 2-12, 10587 Berlin Introduction Characterization of nanoparticle depositions In most cases, bulk-type or micro-scaled reference-materials do not provide Reference-free GIXRF is also suitable for both a chemical and a Ag nanoparticles optimal calibration schemes for analyzing nanomaterials as e.g. surface and dimensional characterization of nanoparticle depositions on flat Si substrate interface contributions may differ from bulk, spatial inhomogeneities may exist substrates. By means of the reference-free quantification, an access to E0 = 3.5 keV at the nanoscale or the response of the analytical method may not be linear deposition densities and other dimensional quantitative measureands over the large dynamic range when going from bulk to the nanoscale. Thus, we is possible. 80% with 9.5 nm diameter have a situation where the availability of suited nanoscale reference materials is By employing also X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAFS), also a 20% with 24.2 nm diameter drastically lower than the current demand. chemical speciation of the nanoparticles or a compound within can be 0.5 nm capping layer performed. Reference-free XRF Nominal 30 nm ZnTiO3 particles: Ti and Zn GIXRF reveals homogeneous Reference-free X-ray fluorescence (XRF), being based on radiometrically particles, Chemical speciation XAFS A calibrated instrumentation, enables an SI traceable quantitative characterization of nanomaterials without the need for any reference material or calibration specimen. -

Enviroinfo 2014 in Oldenburg

Proceedings of the 28th EnviroInfo 2014 Conference, Oldenburg, Germany September 10-12, 2014 Switch off the light in the living room, please! – Making eco-feedback meaningful through room context information Nico Castelli1, Gunnar Stevens2, Timo Jakobi3, Niko Schönau4 Abstract Residential and commercial buildings are responsible for about 40% of the EU’s total energy con- sumption. However, conscious, sustainable use of this limited resource is hampered by a lack of visibility and materiality of consumption. One of the major challenges is enabling consumers to make informed decisions about energy consumption, thereby supporting the shift to sustainable ac- tions. With the use of Energy-Management-Systems it is possible to save up to 15%. In recent years, design approaches have greatly diversified, but with the emergence of ubiquitous- and con- text-aware computing, energy feedback solutions can be enriched with additional context infor- mation. In this study, we present the concept “room as a context” for eco-feedback systems. We investigate opportunities of making current state-of-the-art energy visualizations more meaningful and demonstrate which new forms of visualizations can be created with this additional infor- mation. Furthermore, we developed a prototype for android-based tablets, which includes some of the presented features to study our design concepts in the wild. 1. Introduction Residential and commercial buildings are responsible for about 40% of the EU’s total energy con- sumption [1]. With disaggregated real-time energy consumption feedback, dwellers can be enabled to make better informed energy related decisions and therefore save energy. In general, empirical studies have shown that savings up to 15% [2] can be achieved. -

Braunschweig, 1944-19451 Karl Liedke

Destruction Through Work: Lodz Jews in the Büssing Truck Factory in Braunschweig, 1944-19451 Karl Liedke By early 1944, the influx of foreign civilian workers into the Third Reich economy had slowed to a trickle. Facing the prospect of a severe labor shortage, German firms turned their attention to SS concentration camps, in which a huge reservoir of a potential labor force was incarcerated. From the spring of 1944, the number of labor camps that functioned as branches of concentration camps grew by leaps and bounds in Germany and the occupied territories. The list of German economic enterprises actively involved in establishing such sub-camps lengthened and included numerous well-known firms. Requests for allocations of camp prisoners as a labor force were submitted directly by the firms to the SS Economic Administration Main Office (Wirtschafts- und Verwaltungshauptamt, WVHA), to the head of Department D II – Prisoner Employment (Arbeitseinsatz der Häftlinge), SS-Sturmbannführer Gerhard Maurer. In individual cases these requests landed on the desk of Maurer’s superior, SS-Brigaderführer Richard Glücks, or, if the applicant enjoyed particularly good relations with the SS, on the desk of the head of the WVHA, SS-Gruppenführer Oswald Pohl. Occasionally, representatives of German firms contacted camp commandants directly with requests for prisoner labor-force allocation – in violation of standing procedures. After the allocation of a prisoner labor force was approved, the WVHA and the camp commandant involved jointly took steps to establish a special camp for prisoner workers. Security was the overriding concern; for example, proper fencing, restrictions on contact with civilian workers, etc.