1 Calendar, Clock, Tower John Durham Peters What Is Time?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Astro2020 Science White Paper Solar System Deep Time-Surveys Of

Astro2020 Science White Paper Solar system Deep Time-Surveys of atmospheres, surfaces, and rings Thematic Areas: Planetary Systems Star and Planet Formation Formation and Evolution of Compact Objects Cosmology and Fundamental Physics Stars and Stellar Evolution Resolved Stellar Populations and their Environments Galaxy Evolution Multi-Messenger Astronomy and Astrophysics Principal Author: Name: Michael H. Wong Email: [email protected] Institution: UC Berkeley Phone: 510-224-3411 Co-authors: (names and institutions) Richard Cartwright (SETI Institute) Nancy Chanover (NMSU) Kunio Sayanagi (Hampton University) Thomas Greathouse (SwRI) Matthew Tiscareno (SETI Institute) Rohini Giles (SwRI) Glenn Orton (JPL) David Trilling (Northern Arizona Univeristy) James Sinclair (JPL) Noemi Pinilla-Alonso (Florida Space Institute, UCF) Michael Lucas (UT Knoxville) Eric Gaidos (University of Hawaii) Bryan Holler (STScI) Stephanie Milam (NASA GSFC) Angel Otarola (TMT) Amy Simon (NASA GSFC) Katherine de Kleer (Caltech) Conor Nixon (NASA GSFC) PatricK Fry (Univ. Wisconsin) Máté Ádámkovics (Clemson Univ.) Statia H. LuszcZ-Cook (AMNH) Amanda Hendrix (PSI) Abstract: Imaging and resolved spectroscopy reveal varying environmental conditions in our dynamic solar system. Many key advances have focused on how these conditions change over time. Observatory- level commitments to conduct annual observations of solar system bodies would establish a long- term legacy chronicling the evolution of dynamic planetary atmospheres, surfaces, and rings. Science investigations will use these temporal datasets to address potential biosignatures, circulation and evolution of atmospheres from the edge of the habitable zone to the ice giants, orbital dynamics and planetary seismology with ring systems, exchange between components in the planetary system, and the migration and processing of volatiles on icy bodies, including Ocean Worlds. -

Ijet.V14i18.10763

Paper—Anytime Autonomous English MALL App Engagement Anytime Autonomous English MALL App Engagement https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v14i18.10763 Jason Byrne Toyo University, Tokyo, Japan [email protected] Abstract—Mobile assisted language learning (MALL) apps are often said to be 'Anytime' activities. But, when is 'Anytime' exactly? The objective of the pa- per is to provide evidence for the when of MALL activity around the world. The research method involved the collection and analysis of an EFL app’s time data from 44 countries. The findings were surprising in the actual consistency of us- age, 24/7, across 43 of the 44 countries. The 44th country was interesting in that it differed significantly in terms of night time usage. The research also noted differences in Arab, East Asian and Post-Communist country usage, to what might be construed to be a general worldwide app time usage norm. The results are of interest as the time data findings appear to inform the possibility of a po- tentially new innovative pedagogy based on an emerging computational aware- ness of context and opportunity, suggesting a possible future language learning niche within the Internet of Things (IoT), of prompted, powerful, short-burst, mobile learning. Keywords—CALL, MALL, EFL, IoT, Post-Communist, Saudi Arabia. 1 Introduction 'Learning anytime, anywhere' is one of the most well-known phrases used to de- scribe learning technology [1]. A review of the Mobile Assisted Language Learning (MALL) literature will rapidly bring forth the phrase 'Anytime and anywhere.' But, when exactly is anytime? Is it really 24/7? Or, is it more nuanced? For example, does it vary from country to country, day by day or hour by hour? The literature simply does not provide answers. -

A Brief History of the Great Clock at Westminster Palace

A Brief History of the Great Clock at Westminster Palace Its Concept, Construction, the Great Accident and Recent Refurbishment Mark R. Frank © 2008 A Brief History of the Great Clock at Westminster Palace Its Concept, Construction, the Great Accident and Recent Refurbishment Paper Outline Introduction …………………………………………………………………… 2 History of Westminster Palace………………………………………………... 2 The clock’s beginnings – competition, intrigues, and arrogance …………... 4 Conflicts, construction and completion …………………………………….. 10 Development of the gravity escapement ……………………………………. 12 Seeds of destruction ………………………………………………………….. 15 The accident, its analysis and aftermath …………………………………… 19 Recent major overhaul in 2007 ……………………………………………... 33 Appendix A …………………………………………………………………... 40 Footnotes …………………………………………………………………….. 41 1 Introduction: Big Ben is a character, a personality, the very heart of London, and the clock tower at the Houses of Parliament has become the symbol of Britain. It is the nation’s clock, instantly recognizable, and brought into Britain’s homes everyday by the BBC. It is part of the nation’s heritage and has long been established as the nation’s timepiece heralding almost every broadcast of national importance. On the morning of August 5th 1976 at 3:45 AM a catastrophe occurred to the movement of the great clock in Westminster Palace. The damage was so great that for a brief time it was considered to be beyond repair and a new way to move the hands on the four huge exterior dials was considered. How did this happen and more importantly why did this happen and how could such a disaster to one of the world’s great horological treasures be prevented from happening again? Let us first go through a brief history leading up to the creation of the clock. -

TS4002 Wireless Synchronized Analog Clock Is Designed with an Easy-To-Read Dial Face, Durable Cherry Finished Wood Frame and Tamper-Proof Glass Lens

TS4002 - Wireless Synchronized Analog Clock The TS4002 Wireless Synchronized Analog Clock is designed with an easy-to-read dial face, durable cherry finished wood frame and tamper-proof glass lens. The TS4002 receives a wireless time signal transmitted daily by a main wireless paging controller, such as the VS4800. The TS4002 uses the time signal to automatically adjust itself, if necessary, to ensure accurate and synchronized time throughout the entire facility. The TS4002 does not require any wiring and is ideal for renovation projects and new installations. The TS4002 has a traditional look that matches a wide variety of applications and provides years of maintenance-free service. Key Features: • Viewing Distance of 50' • Automatic Daylight Saving Time Adjustment • Glass Lens • Quick Correction for Time Change (1-3 Minutes) • Flush Mount (Does Not Require Back Box) • Battery Operated (Optional AC Power Adaptor) • Customized Logo Option Options, Accessories and Complementary Products: Part Number Description TS-OPT-003 24-Hour Clock Face TS-OPT-004 Customized Analog Clock Face TS-OPT-005 Sealed Analog Clock TS-OPT-007 110 V AC Adaptor (Replaces Original Clock Batteries, Requires 1.5" Minimum Recessed Power Outlet) TS-OPT-011 Red Second Hand Specifications: Dimensions 19.5" x 8.5" x 2.05" (W x H x D) Dial Face 8", White Weight 5.25 lbs. Frequency VHF (148 - 174 MHz), UHF (400 - 470 MHz) Power Two AA Sized Batteries Paging Format POCSAG, Narrow Band Operating Temperature 32º - 120ºF Synchronization 1 Time/Day (Optional 6 Times/Day, User Selectable) Humidity 0% - 95%, Non-Condensing Receiver Sensitivity 10u V/M Frame and Lens Wood Durable Frame, Glass Lens Limited Warranty One Year Parts and Labor Viewing Distance 50 ft. -

Victorian Popular Science and Deep Time in “The Golden Key”

“Down the Winding Stair”: Victorian Popular Science and Deep Time in “The Golden Key” Geoffrey Reiter t is sometimes tempting to call George MacDonald’s fantasies “timeless”I and leave it at that. Such is certainly the case with MacDonald’s mystical fairy tale “The Golden Key.” Much of the criticism pertaining to this work has focused on its more “timeless” elements, such as its intrinsic literary quality or its philosophical and theological underpinnings. And these elements are not only important, they truly are the most fundamental elements needed for a full understanding of “The Golden Key.” But it is also important to remember that MacDonald did not write in a vacuum, that he was in fact interested in and engaged with many of the pressing issues of his day. At heart always a preacher, MacDonald could not help but interact with these issues, not only in his more openly didactic realistic novels, but even in his “timeless” fantasies. In the Victorian period, an era of discovery and exploration, the natural sciences were beginning to come into their own as distinct and valuable sources of knowledge. John Pridmore, examining MacDonald’s view of nature, suggests that MacDonald saw it as serving a function parallel to the fairy tale or fantastic story; it may be interpreted from the perspective of Christian theism, though such an interpretation is not necessary (7). Björn Sundmark similarly argues that in his works “MacDonald does not contradict science, nor does he press a theistic interpretation onto his readers” (13). David L. Neuhouser has concluded more assertively that while MacDonald was certainly no advocate of scientific pursuits for their own sake, he believed science could be of interest when examined under the aegis of a loving God (10). -

Simulating Dynamic Time Dilation in Relativistic Virtual Environment

International Journal of Computer Theory and Engineering, Vol. 8, No. 5, October 2016 Simulating Dynamic Time Dilation in Relativistic Virtual Environment Abbas Saliimi Lokman, Ngahzaifa Ab. Ghani, and Lok Leh Leong table showing all related activities needed to produce the Abstract—This paper critically reviews several Special objective simulation which is a dynamic Time Dilation effect Relativity simulation applications and proposes a method to in relativistic virtual environment. dynamically simulate Time Dilation effect. To the authors’ knowledge, this has not yet been studied by other researchers. Dynamic in the context of this paper is defined by the ability to persistently simulate Time Dilation effect based on specific II. LITERATURE ON TIME DILATION SIMULATION parameter that can be controlled by user/viewer in real-time A lot of effort to visualize Special Relativity using interactive simulation. Said parameter is the value of speed graphical computerize simulation have been done throughout from acceleration and deceleration of moving observer. In recent years [1]-[7]. Most of them focused on visualizing relativistic environment, changing the speed’s value will also change the Lorentz Factor value thus directly affect the Time relativistic environment from the effect of Lorentz Dilation value. One can simply calculate the dilated time by Transformation. Although it is rare, there is also an attempt to using Time Dilation equation, however if the velocity is not simulate Lorentz Transformation effect in “real world” constant (from implying Special Relativity), one must setting by warping real world camera captured images [8]. repeatedly calculate the dilated time considering the changing Time Dilation however did not get much attention. -

![Arxiv:1601.03132V7 [Math.HO] 15 Nov 2018 [2]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0729/arxiv-1601-03132v7-math-ho-15-nov-2018-2-530729.webp)

Arxiv:1601.03132V7 [Math.HO] 15 Nov 2018 [2]

Solution of the Mayan Calendar Enigma Thomas Chanier1∗ 1Independent researcher, 1025 12th avenue, Coralville, Iowa 52241, USA The Mayan calendar is proposed to derive from an arithmetical model of naked-eye astronomy. The Palenque and Copan lunar equations, used during the Maya Classic period (200 to 900 AD) are solution of the model and the results are expressed as a function of the Xultun numbers, four enigmatic Long Count numbers deciphered in the Maya ruins of Xultun, dating from the IX century AD, providing strong arguments in favor of the use of the model by the Maya. The different Mayan Calendar cycles can be derived from this model and the position of the Calendar Round at the mythical date of creation 13(0).0.0.0.0 4 Ahau 8 Cumku is calculated. This study shows the high proficiency of Mayan mathematics as applied to astronomy and timekeeping for divinatory purposes.a I. INTRODUCTION In the Calendar Round, a date is represented by αXβY with the religious month 1 ≤ α ≤ 13, X one of the 20 Mayan priests-astronomers were known for their astro- religious days, the civil day 0 ≤ β ≤ 19, and Y one of the nomical and mathematical proficiency, as demonstrated 18 civil months, 0 ≤ β ≤ 4 for the Uayeb. Fig. 1 shows a in the Dresden Codex, a XIV century AD bark-paper contemporary representation of the Calendar Round as book containing accurate astronomical almanacs aiming a set of three interlocking wheels: the Tzolk'in, formed to correlate ritual practices with astronomical observa- by a 13-month and a 20-day wheels and the Haab'. -

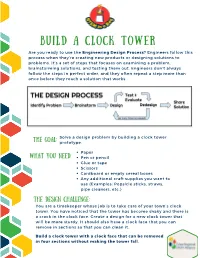

Clock Tower STEM in A

build a clock tower Are you ready to use the Engineering Design Process? Engineers follow this process when they’re creating new products or designing solutions to problems. It’s a set of steps that focuses on examining a problem, brainstorming solutions, and testing them out. Engineers don’t always follow the steps in perfect order, and they often repeat a step more than once before they reach a solution that works. The Goal: Solve a design problem by building a clock tower prototype. Paper what you need: Pen or pencil Glue or tape Scissors Cardboard or empty cereal boxes Any additional craft supplies you want to use (Examples: Popsicle sticks, straws, pipe cleaners, etc.) The Design challenge: You are a timekeeper whose job is to take care of your town’s clock tower. You have noticed that the tower has become shaky and there is a crack in the clock face. Create a design for a new clock tower that will be more sturdy. It should also have a clock face that you can remove in sections so that you can clean it. Build a clock tower with a clock face that can be removed in four sections without making the tower fall. build a clock tower CONt. design it Gather all of your materials and examine them. Think about how you might use each of them to build your clock tower. Architects draw blueprints of their buildings before they build them. A blueprint is a drawing of what you want your construction to look like, and it helps you plan how you are going to build something. -

Yesterday, Today, and Forever Hebrews 13:8 a Sermon Preached in Duke University Chapel on August 29, 2010 by the Revd Dr Sam Wells

Yesterday, Today, and Forever Hebrews 13:8 A Sermon preached in Duke University Chapel on August 29, 2010 by the Revd Dr Sam Wells Who are you? This is a question we only get to ask one another in the movies. The convention is for the question to be addressed by a woman to a handsome man just as she’s beginning to realize he isn’t the uncomplicated body-and-soulmate he first seemed to be. Here’s one typical scenario: the war is starting to go badly; the chief of the special unit takes a key officer aside, and sends him on a dangerous mission to infiltrate the enemy forces. This being Hollywood, the officer falls in love with a beautiful woman while in enemy territory. In a moment of passion and mystery, it dawns on her that he’s not like the local men. So her bewitched but mistrusting eyes stare into his, and she says, “Who are you?” Then there’s the science fiction version. In this case the man develops an annoying habit of suddenly, without warning, traveling in time, or turning into a caped superhero. Meanwhile the woman, though drawn to his awesome good looks and sympathetic to his commendable desire to save the universe, yet finds herself taking his unexpected and unusual absences rather personally. So on one of the few occasions she gets to look into his eyes when they’re not undergoing some kind of chemical transformation, she says, with the now-familiar, bewitched-but-mistrusting expression, “Who are you?” “Who are you?” We never ask one another this question for fear of sounding melodramatic, like we’re in a movie. -

The Clock Tower

Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia — The Clock Tower ENG The Clock Tower The Clock Tower is one of the most famous architectural landmarks in Venice, standing over an arch that leads into what is the main shopping street of the city, the old Merceria. It marks both a juncture and a division between the various architectural components of St. Mark’s Square, which was not only the seat of political and religious power but also a public space and an area of economic activity, a zone that looked out towards the sea and also played a functional role as a hub for the entire layout of the city. In short, the Tower and its large Astronomical Clock, a masterpiece of technology and engineering, form an essential part of the very image of Venice. THE HISTORY As is known, the decision to erect a new public clock in the St. Mark’s area to replace the inadequate, old clock of Sant’Alipio on the north-west corner of the Basilica – which was by then going to rack and ruin – predates the decision as to where this new clock was to be placed. It was 1493 when the Senate commissioned Carlo Zuan Rainieri of Reggio Emilia to create a new clock, but the decision that this was to be erected over the entrance to the Merceria only came two years later. Procuratie Vechie and Bocha de According to Marin Sanudo, the following year “on 10 June work Marzaria began on the demolition of the houses at the entrance to the Merceria (…) to lay down the foundations for the most excellent clock”. -

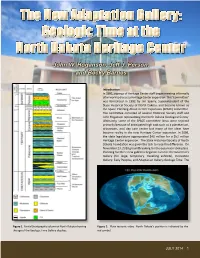

The New Adaption Gallery

Introduction In 1991, a group of Heritage Center staff began meeting informally after work to discuss a Heritage Center expansion. This “committee” was formalized in 1992 by Jim Sperry, Superintendent of the State Historical Society of North Dakota, and became known as the Space Planning About Center Expansion (SPACE) committee. The committee consisted of several Historical Society staff and John Hoganson representing the North Dakota Geological Survey. Ultimately, some of the SPACE committee ideas were rejected primarily because of anticipated high cost such as a planetarium, arboretum, and day care center but many of the ideas have become reality in the new Heritage Center expansion. In 2009, the state legislature appropriated $40 million for a $52 million Heritage Center expansion. The State Historical Society of North Dakota Foundation was given the task to raise the difference. On November 23, 2010 groundbreaking for the expansion took place. Planning for three new galleries began in earnest: the Governor’s Gallery (for large, temporary, travelling exhibits), Innovation Gallery: Early Peoples, and Adaptation Gallery: Geologic Time. The Figure 1. Partial Stratigraphic column of North Dakota showing Figure 2. Plate tectonic video. North Dakota's position is indicated by the the age of the Geologic Time Gallery displays. red symbol. JULY 2014 1 Orientation Featured in the Orientation area is an interactive touch table that provides a timeline of geological and evolutionary events in North Dakota from 600 million years ago to the present. Visitors activate the timeline by scrolling to learn how the geology, environment, climate, and life have changed in North Dakota through time. -

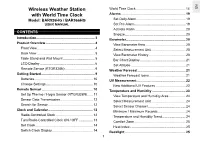

BAR926HG.Pdf

Wireless Weather Station World Time Clock .....................................................14 EN with World Time Clock Alarms ..................................................................... 19 Model: BAR926HG / BAR966HG Set Daily Alarm ..................................................... 19 USER MANUAL Set Pre-Alarm ....................................................... 19 Activate Alarm ...................................................... 20 CONTENTS Snooze ................................................................. 20 Introduction ............................................................... 3 Barometer ................................................................ 20 Product Overview ..................................................... 4 View Barometer Area ........................................... 20 Front View .............................................................. 4 Select Measurement Unit ..................................... 20 Back View .............................................................. 5 View Barometer History ....................................... 20 Table Stand and Wall Mount .............................. 5 Bar Chart Display ................................................. 21 LCD Display ........................................................... 6 Set Altitude ........................................................... 21 Remote Sensor (RTGR328N) ................................ 9 Weather Forecast ................................................... 21 Getting Started .........................................................