Optimized Design of OTA-Based Gyrator Realizing Fractional-Order Inductance Simulator: a Comprehensive Analysis †

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electrical Circuits Lab. 0903219 Series RC Circuit Phasor Diagram

Electrical Circuits Lab. 0903219 Series RC Circuit Phasor Diagram - Simple steps to draw phasor diagram of a series RC circuit without memorizing: * Start with the quantity (voltage or current) that is common for the resistor R and the capacitor C, which is here the source current I (because it passes through both R and C without being divided). Figure (1) Series RC circuit * Now we know that I and resistor voltage VR are in phase or have the same phase angle (there zero crossings are the same on the time axis) and VR is greater than I in magnitude. * Since I equal the capacitor current IC and we know that IC leads the capacitor voltage VC by 90 degrees, we will add VC on the phasor diagram as follows: * Now, the source voltage VS equals the vector summation of VR and VC: Figure (2) Series RC circuit Phasor Diagram Prepared by: Eng. Wiam Anabousi - Important notes on the phasor diagram of series RC circuit shown in figure (2): A- All the vectors are rotating in the same angular speed ω. B- This circuit acts as a capacitive circuit and I leads VS by a phase shift of Ө (which is the current angle if the source voltage is the reference signal). Ө ranges from 0o to 90o (0o < Ө <90o). If Ө=0o then this circuit becomes a resistive circuit and if Ө=90o then the circuit becomes a pure capacitive circuit. C- The phase shift between the source voltage and its current Ө is important and you have two ways to find its value: a- b- = - = - D- Using the phasor diagram, you can find all needed quantities in the circuit like all the voltages magnitude and phase and all the currents magnitude and phase. -

Phasor Analysis of Circuits

Phasor Analysis of Circuits Concepts Frequency-domain analysis of a circuit is useful in understanding how a single-frequency wave undergoes an amplitude change and phase shift upon passage through the circuit. The concept of impedance or reactance is central to frequency-domain analysis. For a resistor, the impedance is Z ω = R , a real quantity independent of frequency. For capacitors and R ( ) inductors, the impedances are Z ω = − i ωC and Z ω = iω L. In the complex plane C ( ) L ( ) these impedances are represented as the phasors shown below. Im ivL R Re -i/vC These phasors are useful because the voltage across each circuit element is related to the current through the equation V = I Z . For a series circuit where the same current flows through each element, the voltages across each element are proportional to the impedance across that element. Phasor Analysis of the RC Circuit R V V in Z in Vout R C V ZC out The behavior of this RC circuit can be analyzed by treating it as the voltage divider shown at right. The output voltage is then V Z −i ωC out = C = . V Z Z i C R in C + R − ω + The amplitude is then V −i 1 1 out = = = , V −i +ω RC 1+ iω ω 2 in c 1+ ω ω ( c ) 1 where we have defined the corner, or 3dB, frequency as 1 ω = . c RC The phasor picture is useful to determine the phase shift and also to verify low and high frequency behavior. The input voltage is across both the resistor and the capacitor, so it is equal to the vector sum of the resistor and capacitor voltages, while the output voltage is only the voltage across capacitor. -

5 RC Circuits

Physics 212 Lab Lab 5 RC Circuits What You Need To Know: The Physics In the previous two labs you’ve dealt strictly with resistors. In today’s lab you’ll be using a new circuit element called a capacitor. A capacitor consists of two small metal plates that are separated by a small distance. This is evident in a capacitor’s circuit diagram symbol, see Figure 1. When a capacitor is hooked up to a circuit, charges will accumulate on the plates. Positive charge will accumulate on one plate and negative will accumulate on the other. The amount of charge that can accumulate is partially dependent upon the capacitor’s capacitance, C. With a charge distribution like this (i.e. plates of charge), a uniform electric field will be created between the plates. [You may remember this situation from the Equipotential Surfaces lab. In the lab, you had set-ups for two point-charges and two lines of charge. The latter set-up represents a capacitor.] A main function of a capacitor is to store energy. It stores its energy in the electric field between the plates. Battery Capacitor (with R charges shown) C FIGURE 1 - Battery/Capacitor FIGURE 2 - RC Circuit If you hook up a battery to a capacitor, like in Figure 1, positive charge will accumulate on the side that matches to the positive side of the battery and vice versa. When the capacitor is fully charged, the voltage across the capacitor will be equal to the voltage across the battery. You know this to be true because Kirchhoff’s Loop Law must always be true. -

ELECTRICAL CIRCUIT ANALYSIS Lecture Notes

ELECTRICAL CIRCUIT ANALYSIS Lecture Notes (2020-21) Prepared By S.RAKESH Assistant Professor, Department of EEE Department of Electrical & Electronics Engineering Malla Reddy College of Engineering & Technology Maisammaguda, Dhullapally, Secunderabad-500100 B.Tech (EEE) R-18 MALLA REDDY COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY II Year B.Tech EEE-I Sem L T/P/D C 3 -/-/- 3 (R18A0206) ELECTRICAL CIRCUIT ANALYSIS COURSE OBJECTIVES: This course introduces the analysis of transients in electrical systems, to understand three phase circuits, to evaluate network parameters of given electrical network, to draw the locus diagrams and to know about the networkfunctions To prepare the students to have a basic knowledge in the analysis of ElectricNetworks UNIT-I D.C TRANSIENT ANALYSIS: Transient response of R-L, R-C, R-L-C circuits (Series and parallel combinations) for D.C. excitations, Initial conditions, Solution using differential equation and Laplace transform method. UNIT - II A.C TRANSIENT ANALYSIS: Transient response of R-L, R-C, R-L-C Series circuits for sinusoidal excitations, Initial conditions, Solution using differential equation and Laplace transform method. UNIT - III THREE PHASE CIRCUITS: Phase sequence, Star and delta connection, Relation between line and phase voltages and currents in balanced systems, Analysis of balanced and Unbalanced three phase circuits UNIT – IV LOCUS DIAGRAMS & RESONANCE: Series and Parallel combination of R-L, R-C and R-L-C circuits with variation of various parameters.Resonance for series and parallel circuits, concept of band width and Q factor. UNIT - V NETWORK PARAMETERS:Two port network parameters – Z,Y, ABCD and hybrid parameters.Condition for reciprocity and symmetry.Conversion of one parameter to other, Interconnection of Two port networks in series, parallel and cascaded configuration and image parameters. -

How to Design Analog Filter Circuits.Pdf

a b FIG. 1-TWO LOWPASS FILTERS. Even though the filters use different components, they perform in a similiar fashion. MANNlE HOROWITZ Because almost every analog circuit contains some filters, understandinghow to work with them is important. Here we'll discuss the basics of both active and passive types. THE MAIN PURPOSE OF AN ANALOG FILTER In addition to bandpass and band- age (because inductors can be expensive circuit is to either pass or reject signals rejection filters, circuits can be designed and hard to find); they are generally easier based on their frequency. There are many to only pass frequencies that are either to tune; they can provide gain (and thus types of frequency-selective filter cir- above or below a certain cutoff frequency. they do not necessarily have any insertion cuits; their action can usually be de- If the circuit passes only frequencies that loss); they have a high input impedance, termined from their names. For example, are below the cutoff, the circuit is called a and have a low output impedance. a band-rejection filter will pass all fre- lo~~passfilter, while a circuit that passes A filter can be in a circuit with active quencies except those in a specific band. those frequencies above the cutoff is a devices and still not be an active filter. Consider what happens if a parallel re- higlzpass filter. For example, if a resonant circuit is con- sonant circuit is connected in series with a All of the different filters fall into one . nected in series with two active devices signal source. -

The Stripline Circulator Theory and Practice

The Stripline Circulator Theory and Practice By J. HELSZAJN The Stripline Circulator The Stripline Circulator Theory and Practice By J. HELSZAJN Copyright # 2008 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http:// www.wiley.com/go/permission. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages. -

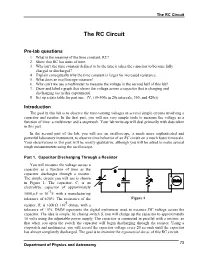

The RC Circuit

The RC Circuit The RC Circuit Pre-lab questions 1. What is the meaning of the time constant, RC? 2. Show that RC has units of time. 3. Why isn’t the time constant defined to be the time it takes the capacitor to become fully charged or discharged? 4. Explain conceptually why the time constant is larger for increased resistance. 5. What does an oscilloscope measure? 6. Why can’t we use a multimeter to measure the voltage in the second half of this lab? 7. Draw and label a graph that shows the voltage across a capacitor that is charging and discharging (as in this experiment). 8. Set up a data table for part one. (V, t (0-300s in 20s intervals, 360, and 420s)) Introduction The goal in this lab is to observe the time-varying voltages in several simple circuits involving a capacitor and resistor. In the first part, you will use very simple tools to measure the voltage as a function of time: a multimeter and a stopwatch. Your lab write-up will deal primarily with data taken in this part. In the second part of the lab, you will use an oscilloscope, a much more sophisticated and powerful laboratory instrument, to observe time behavior of an RC circuit on a much faster timescale. Your observations in this part will be mostly qualitative, although you will be asked to make several rough measurements using the oscilloscope. Part 1. Capacitor Discharging Through a Resistor You will measure the voltage across a capacitor as a function of time as the capacitor discharges through a resistor. -

Doppler-Based Acoustic Gyrator

applied sciences Article Doppler-Based Acoustic Gyrator Farzad Zangeneh-Nejad and Romain Fleury * ID Laboratory of Wave Engineering, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland; farzad.zangenehnejad@epfl.ch * Correspondence: romain.fleury@epfl.ch; Tel.: +41-412-1693-5688 Received: 30 May 2018; Accepted: 2 July 2018; Published: 3 July 2018 Abstract: Non-reciprocal phase shifters have been attracting a great deal of attention due to their important applications in filtering, isolation, modulation, and mode locking. Here, we demonstrate a non-reciprocal acoustic phase shifter using a simple acoustic waveguide. We show, both analytically and numerically, that when the fluid within the waveguide is biased by a time-independent velocity, the sound waves travelling in forward and backward directions experience different amounts of phase shifts. We further show that the differential phase shift between the forward and backward waves can be conveniently adjusted by changing the imparted bias velocity. Setting the corresponding differential phase shift to 180 degrees, we then realize an acoustic gyrator, which is of paramount importance not only for the network realization of two port components, but also as the building block for the construction of different non-reciprocal devices like isolators and circulators. Keywords: non-reciprocal acoustics; gyrators; phase shifters; Doppler effect 1. Introduction Microwave phase shifters are two-port components that provide an arbitrary and variable transmission phase angle with low insertion loss [1–3]. Since their discovery in the 19th century, such phase shifters have found important applications in devices such as phased array antennas and receivers [4,5], beam forming and steering networks [6,7], measurement and testing systems [8,9], filters [10,11], modulators [12,13], frequency up-convertors [14], power flow controllers [15], interferometers [16], and mode lockers [17]. -

Capacitors, Inductors, and First-Order Linear Circuits Overview

EECE251 Circuit Analysis I Set 4: Capacitors, Inductors, and First-Order Linear Circuits Shahriar Mirabbasi Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering University of British Columbia [email protected] SM 1 EECE 251, Set 4 Overview • Passive elements that we have seen so far: resistors. We will look into two other types of passive components, namely capacitors and inductors. • We have already seen different methods to analyze circuits containing sources and resistive elements. • We will examine circuits that contain two different types of passive elements namely resistors and one (equivalent) capacitor (RC circuits) or resistors and one (equivalent) inductor (RL circuits) • Similar to circuits whose passive elements are all resistive, one can analyze RC or RL circuits by applying KVL and/or KCL. We will see whether the analysis of RC or RL circuits is any different! Note: Some of the figures in this slide set are taken from (R. Decarlo and P.-M. Lin, Linear Circuit Analysis , 2nd Edition, 2001, Oxford University Press) and (C.K. Alexander and M.N.O Sadiku, Fundamentals of Electric Circuits , 4th Edition, 2008, McGraw Hill) SM 2 EECE 251, Set 4 1 Reading Material • Chapters 6 and 7 of the textbook – Section 6.1: Capacitors – Section 6.2: Inductors – Section 6.3: Capacitor and Inductor Combinations – Section 6.5: Application Examples – Section 7.2: First-Order Circuits • Reading assignment: – Review Section 7.4: Application Examples (7.12, 7.13, and 7.14) SM 3 EECE 251, Set 4 Capacitors • A capacitor is a circuit component that consists of two conductive plate separated by an insulator (or dielectric). -

Inductors and Capacitors in AC Circuits

Inductors and Capacitors in AC Circuits IMPORTANT NOTE: A USB flash drive is needed for the first section of this lab. Make sure to bring one with you! Introduction The goal of this lab is to look at the behaviour of inductors and capacitors - two circuit components which may be new to you. In AC circuits currents vary in time, therefore we have to consider variations in the energy stored in electric and magnetic fields of capacitors and inductors, respectively. You are already familiar with resistors, where the voltage-current relation is given by Ohm's law: VR(t) = RI(t); (1) In an inductor, the voltage is proportional to the rate of change of the current. You may recall the example of a coil of wire, where changing the current changes the magnetic flux, creating a voltage in the opposite direction (Lenz's law). A capacitor is a component where a charge difference builds up across the component. A simple example of this is a pair of parallel plates separated by a small distance, with a charge difference between them. The potential difference between the plates depends on the charge difference Q, which can also be written as the integral over time of the current flowing into/out of the capacitor. Inductors and capacitors are characterized by their inductance L and capacitance C respectively, with the voltage difference across them given by dI(t) V (t) = L ; (2) L dt Z t Q(t) 1 0 0 VC (t) = = I(t )dt (3) C C 0 1 Transient Behaviour In this first section, we'll look at how circuits with these components behave when an applied DC voltage is switched from one value to another. -

Switched Capacitor Networks and Techniques for the Period 19 1-1992

Active and Passive Elec. Comp., 1994, Vol. 16, pp. 171-258 Reprints available directly from the publisher Photocopying permitted by license only 1994 Gordon and Breach Science Publishers S.A. Printed in Malaysia A CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF REFERENCES ON SWITCHED CAPACITOR NETWORKS AND TECHNIQUES FOR THE PERIOD 19 1-1992 A.K. SINGH Electronics Lab., Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering, Delhi Institute of Technology, Kashmere Gate, Delhi 110006, India. (Received November 16, 1993; in final form December 15, 1993) A chronological list of 440 references on switched capacitor (SC) networks from 1939 to May 1981 was published in this Journal by J. Vandewalle. In this communication, we present a compilation of 1357 references covering the period from May 1981-1992 (along with a supplementary list of 43 missing references for the period before May 1981). The present compilation and the earlier one by Vandewalle put together, thus, constitute an exhaustive bibliography of 1797 references on SC-networks and tech- niques till 1992. I. INTRODUCTION The importance of SC-networks in the area of instrumentation and communication is well established. Because of their suitability to VLSI implementation, along with digital networks on the same chip and their low cost coupled with accuracy, SC- networks have greatly enhanced their applicability in the electronics world. Enor- mous volumes of literature on the SC-techniques for different applications is now available. Many design procedures including those based upon immittance simu- lation and wave concepts have been evolved. Application of SC-networks in the design of FIR and IIR filters and neural networks have also been reported. -

Modeling & Simulation 2019 Lecture 8. Bond Graphs

Modeling & Simulation 2019 Lecture 8. Bond graphs Claudio Altafini Automatic Control, ISY Linköping University, Sweden 1 / 45 Summary of lecture 7 • General modeling principles • Physical modeling: dimension, dimensionless quantities, scaling • Models from physical laws across different domains • Analogies among physical domains 2 / 45 Lecture 8. Bond graphs Summary of today • Analogies among physical domains • Bond graphs • Causality In the book: Chapter 5 & 6 3 / 45 Basic physics laws: a survey Electrical circuits Hydraulics Mechanics – translational Thermal systems Mechanics – rotational 4 / 45 Electrical circuits Basic quantities: • Current i(t) (ampere) • Voltage u(t) (volt) • Power P (t) = u(t) · i(t) 5 / 45 Electrical circuits Basic laws relating i(t) and u(t) • inductance d 1 Z t L i(t) = u(t) () i(t) = u(s)ds dt L 0 • capacitance d 1 Z t C u(t) = i(t) () u(t) = i(s)ds dt C 0 • resistance (linear case) u(t) = Ri(t) 6 / 45 Electrical circuits Energy storage laws for i(t) and u(t) • electromagnetic energy 1 T (t) = Li2(t) 2 • electric field energy 1 T (t) = Cu2(t) 2 • energy loss in a resistance Z t Z t Z t 1 Z t T (t) = P (s)ds = u(s)i(s)ds = R i2(s)ds = u2(s)ds 0 0 0 R 0 7 / 45 Electrical circuits Interconnection laws for i(t) and u(t) • Kirchhoff law for voltages On a loop: ( X +1; σk aligned with loop direction σkuk(t) = 0; σk = −1; σ against loop direction k k • Kirchhoff law for currents On a node: ( X +1; σk inward σkik(t) = 0; σk = −1; σ outward k k 8 / 45 Electrical circuits Transformations laws for u(t) and i(t) • transformer u1 = ru2 1 i = i 1 r 2 u1i1 = u2i2 ) no power loss • gyrator u1 = ri2 1 i = u 1 r 2 u1i1 = u2i2 ) no power loss 9 / 45 Electrical circuits Example State space model: d 1 i = (u − Ri − u ) dt L s C d 1 u = i dt C C 10 / 45 Mechanical – translational Basic quantities: • Velocity v(t) (meters per second) • Force F (t) (newton) • Power P (t) = F (t) · v(t) 11 / 45 Mechanical – translational Basic laws relating F (t) and v(t) • Newton second law d 1 Z t m v(t) = F (t) () v(t) = F (s)ds dt m 0 • Hook’s law (elastic bodies, e.g.