German Immigrants in Nottingham During the First World War by Ben

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The British Press and Zionism in Herzl's Time (1895-1904)* BENJAMIN JAFFE, MA., M.Jur

The British Press and Zionism in Herzl's Time (1895-1904)* BENJAMIN JAFFE, MA., M.Jur. A but has been extremely influential; on the other hand, it is not easy, and may even be It is a to to the Historical privilege speak Jewish to evaluate in most cases a impossible, public Society on subject which is very much interest in a subject according to items or related to its founder and past President, articles in a published newspapers many years the late Lucien Wolf. Wolf has prominent ago. It is clear that Zionism was at the period place in my research, owing to his early in question a marginal topic from the point of contacts with Herzl and his opposition to view of the public, and the Near East issue Zionism in later an which years, opposition was not in the forefront of such interest. him to his latest The accompanied day. story We have also to take into account that the of the Herzl-Wolf relationship is an interesting number of British Jews was then much smaller chapter in the history of early British Zionism than today, and the Jewish public as newspaper and Wolf's life.i readers was limited, having It was not an venture to naturally quite easy prepare were regard also to the fact that many of them comprehensive research on the attitude of the newly arrived immigrants who could not yet British press at the time of Herzl. Early read English. Zionism in in attracted England general only I have concentrated here on Zionism as few scholars, unless one mentions Josef Fraenkel reflected in the British press in HerzPs time, and the late Oskar K. -

APPENDIX I the Carlton Club Meeting, 19 October 1922

APPENDIX I The Carlton Club Meeting, 19 October 1922 This appendix lists the vote at the Carlton Club Meeting of all Conservative M.P.s It is based on a list in the Austen Chamber lain Papers (AC/33/2/92), and has been checked against public statements by the M.P.s of their votes at the meeting. In two cases the public statements disagreed with Chamberlain's list. They were Sir R. Greene (Hackney North) and C. Erskine-Bolst (Hackney South). Chamberlaine's list said that Greene supported the Coalition, while Erskine-Bolst opposed it. The two men indicated that they had the opposite opinion, and their votes may have been transposed in Chamberlain's list. The appendix gives information on the attitude of Conserva tive M.P.s towards the Coalition before the Carlton Club Meet ing, and it also lists some M.P.s who were present but who according to Chamberlain did not vote. R. R. James, using a different source, published a list of the M.P.s voting at the Carlton Club (Memoirs Of A Conservative, 130-3). He gave the total vote as 185 opponents of the Coalition, and 88 supporters, and he lists 184 opponents of the Coalition. M.P.s who were listed differently from Chamberlain's accounting were: H. C. Brown (Chamberlain, anti; James, absent) C. Carew (Chamberlain, absent; James, pro) G. L. Palmer (Chamberlain, absent; James, anti) H. Ratcliffe (Chamberlain, absent; James, pro) 222 THE FALL OF LLOYD GEORGE N. Raw (Chamberlain, absent; James, anti) R. G. Sharman-Crawford (Chamberlain, anti; James, absent) R. -

The Valentine Has Fallen Upon Evil Days

This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced PDF of an article accepted for publication in Early Popular Visual Culture journal, following peer review. The published version: Annebella Pollen, ‘”The Valentine has fallen upon evil days”: Mocking Victorian valentines and the ambivalent laughter of the carnivalesque’, Early Popular Visual Culture, special issue: Social Control and Early Visual Culture, Vol 12, Iss, 2, 2014, pp. 127-173, first published online August 21, 2014 can be found here: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17460654.2014.924212?journalCode=repv20 DOI: 10.1080/17460654.2014.924212 ‘The Valentine has fallen upon evil days’: Mocking Victorian valentines and the ambivalent laughter of the carnivalesque Annebella Pollen, School of Humanities, University of Brighton This article examines the social control embodied and enacted in the practices of sending and receiving mocking valentine cards in the Victorian era. Particularly popular in the period 1840-1880, cheaply-printed and cheaply-sold ‘mock’ or ‘mocking’, comic valentines were the inverse of their better-known sentimental print partners. Usually featuring a crude caricature, intended to represent the recipient, and a satirical accompanying verse, such cards had a much wider network than today’s cards. Mocking valentines covered a vast range of ‘types’ and could be sent to neighbours, colleagues and members of the local community as well as to wanting and unwanted partners. Each was designed to highlight a particular social ill, from poor manners and hygiene to pretentiousness and alcoholism, sometimes with astonishing cruelty. As such, for all their purported comical intention, these printed missives critiqued behaviour that deviated from social norms, and could chide, shame and scapegoat. -

The State and the Country House in Nottinghamshire, 1937-1967

THE STATE AND THE COUNTRY HOUSE IN NOTTINGHAMSHIRE, 1937-1967 Matthew Kempson, BSc. MA. Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2006 Abstract This thesis considers the state preservation and use of Nottinghamshire country houses during the mid-twentieth century, from the initiation of mass requisition in 1937 until 1967 when concerns for architectural preservation moved away from the country house. This thesis reviews literature on the landed estate in the twentieth century and the emergence of preservationist claims on the country house. Three substantive sections follow. The first discusses the declining representation of landowners within local governance in Nottinghamshire and the constitution of the County Council, and considers how estate space was incorporated within broadened concerns for the preservation of the historic environment and additionally provided the focus for the implementation of a variety of modern state and non-state functions. The second section considers how changing policy and aesthetic judgements impacted upon the preservation of country houses. Through discussion of Rufford Abbey, Winkburn Hall and Ossington Hall I consider the complexities of preservationist claims and how these conflicted with the responsibilities of the state and the demands of private landowners. The third section considers how estate space became valued by local authorities in the implementation of a variety of new modern educational uses, including the teacher training college at Eaton Hall and a school campus development at Bramcote Hills. The thesis concludes by considering the status of the country house in Nottinghamshire since 1967, and contemporary demands on the spaces considered historically in this study. -

Catalogue of the Collections of Sir Aurel Stein in the Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences

Catalogue of the Collections of Sir Aurel Stein in the Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences edited by Éva Apor and Helen Wang THE BRITISH MUSEUM Budapest 2002 CATALOGUE OF THE COLLECTIONS OF SIR AUREL STEIN IN THE LIBRARY OF THE HUNGARIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES KELETI TANULMÁNYOK ORIENTAL STUDIES 11 SERIES EDITOR: ÉVA APOR © Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences Sponsored by THE BRITISH ACADEMY THE BRITISH COUNCIL THE BRITISH MUSEUM THE HUNGARIAN SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH FUND (OTKA T029152) THE HUNGARIAN SCHOLARSHIP BOARD THE KOMATSU CHIKO FOUNDATION (KYOTO) ISBN: 963 7451 110 ISSN: 0133-6193 THE BRITISH MUSEUM CATALOGUE OF THE COLLECTIONS OF SIR AUREL STEIN IN THE LIBRARY OF THE HUNGARIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES Compiled by JOHN FALCONER - ÁGNES KÁRTESZI - ÁGNES KELECSÉNYI - LILLA RUSSELL-SMITH Edited by ÉVA APOR AND HELEN WANG Ml[ Ä 1826 K BUDAPEST 2002 Sir Aurel Stein (1862-1943) CONTENTS Editors' Preface KELECSÉNYI Ágnes: Sir Aurel Stein and the Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences 13 KELECSÉNYI Ágnes and KÁRTESZI Ágnes: Catalogue of Correspondence, Manuscripts, Documents and Reviews Relating to Sir Aurel Stein 33 Correspondence 33 Manuscripts and Documents 104 Articles, Offprints and Reviews 121 FALCONER John and RUSSELL-SMITH Lilla: Catalogue of Photographs Taken or Collected by Sir Aurel Stein .... 159 Photographs 161 Index to the Photograph Collections 339 EDITORS' PREFACE This volume is the result of a three year project to catalogue the collections of Sir Aurel Stein in the Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. The project was bom out of professional respect and friendly curiosity. It was well known that the Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences held collections relating to Sir Aurel Stein, but there was little indication of the scope of these collections. -

Community and the Voluntary Hospitals in Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire, 1900-1946: Economy, Society, Culture. Edward Cheetham A

Community and the Voluntary Hospitals in Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire, 1900-1946: Economy, Society, Culture. Edward Cheetham A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Nottingham Trent University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In collaboration with the Midlands 4 Cities Doctoral Training Partnership September 2020 i Copyright Statement The copyright in this work is held by the author. You may copy up to 5% of this work for private study, or personal, non-commercial research. Any re-use of the information contained within this document should be fully referenced, quoting the author, title, university, degree level and pagination. Queries or requests for any other use, or if a more substantial copy is required, should be directed to the author. ii Acknowledgements Firstly, I would like to thank my supervisor, Nick Hayes, for the constant support and hard work he has put into this thesis with me. Over these last few years, he has become a true friend and confidant. My wife, Alice, and daughter, Edith, whose love, patience, and fortitude have made this long piece of work possible. My parents, who have supported me every step of the way, in this, and throughout my life. My friends and family, too numerous to mention, who have made this difficult undertaking so much more tolerable with their humour and love. Further to these thanks, I would like to add my sincere gratitude to the workers and archivists of the Derbyshire Record Office, who welcomed me and my research, and aided me in countless ways. iii Abstract This thesis spans the first half of the 20th Century, charting the progress and challenges of the voluntary hospital system in Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire. -

The Origins and Development of Association Football in Nottinghamshire C.1860-1915

The Origins and Development of Association Football in Nottinghamshire c.1860-1915 Andrew Charles Cennydd Dawes Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for PhD Degree awarded by De Montfort University Submission date: April 2017 Contents Page Number Abstract 5 List of Tables and Figures 6 List of Abbreviations 6 Acknowledgements 7 Introduction 8 Football and History 9 Nottinghamshire 18 Professionals and Amateurs 22 Pride of Place: City and County 32 Sources and Methodology 40 Title and Structure of Thesis 44 Chapter One - The Emergence of a ‘football kicking fraternity’, c.1860-1880 49 The Foundations of Football in Nottinghamshire 54 Developing Networks 63 Rules, Officials, Players and Tactics: Towards Uniformity 77 Conclusion 91 Chapter Two - Nottinghamshire, its Press and the FA Cup: ‘Bringing professionalism to the front, 1880-1885’ 95 The Press, Local Patriotism and the FA Cup 100 The Clubs, the County FA and Professionalism 117 2 ‘It works in Cricket, why not Football?’ Nottinghamshire and Professionalism 124 Conclusion 135 Chapter Three - A Footballing Culture, c. 1885-1892 138 The Press and Football in Nottinghamshire 142 Establishing Respectability 152 Popular Culture and Fundraising 161 ‘Lamb-like’ Nottingham 164 Nottinghamshire and Developments in English football 172 Conclusion 185 Chapter Four - Football, Loyalties and Identity in Nottinghamshire c. 1890- 1900 187 City, Identity and Sport 189 Winning the Cup 193 Town, City and County 202 Nottingham as a Regional Football Capital 215 Conclusion 221 Chapter Five - Narrowing ambitions, widening horizons: Nottinghamshire football, 1900-1915 225 Nottinghamshire and English Football’s New Wave 228 The Press and Nottinghamshire Football 248 Nottinghamshire and English Football’s ‘Great Split’, 1907-14 253 Trade and Tours 267 Conclusion 278 3 Conclusion 281 Appendices 295 Bibliography 313 4 Abstract Home to two of the oldest football clubs in the world, Nottinghamshire was a hub of the association game. -

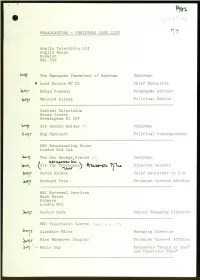

Kuoci-In Director General David Holmes� Chief Assistant to D/G

BROADCAS ING - CHRISTMAS CARD LIST Anglia Television Ltd Anglia House Norwich NR1 3JG The Marquess Townshend of Raynham Chairman * Lord Buxton MC DL Chief Executive -64-r- Brian Connell Programme Adviser Malcolm Allsop Political Editor Central Television Broad Street Birmingham Bl 2JP 1,11 Sir Gordon Hobday Chairman Reg Harcourt Political Correspondent BBC Broadcasting House London W1A IAA The Hon George Howard Chairman 10'r tanrtaVu.t (Sir Ian Trethowar) kuoci-iN Director General David Holmes Chief Assistant to D/G Bernard Tate Producer Current Affairs BBC External Services Bush House Aldwych London WC2 Austen Kark De,outy Managing Director BBC Television Contre Alasdair Milne M,,,,-nging Director ;:iss Margaret Dougla'.= Producer Current Affairs 4-1") Robin Day Presenter "World at One" aud "Question Time" • Border Television Television Centre Carlisle CA1 3NT 4.117 Professor Esmond Wright Chairman 1411 Sir John Burgess OBE TD DL JP Vice Chairman 1 James Bredin Managing Director Grampian Television Queen's Cross Aberdeen AB9 2XJ TT Cabtain lain Tennant JP Chairman Granada Television 36 Golden Square London W1R 4AH )3411 Alex Bernstein Deputy Chairman 104-41-1Sir Denis Forman OBE Chairman 14-r\1David Plowright Joint M/D 1411 Donald Harker Director of Public Affairs 1 Barrie Heads M/D Granada Intn'l HTV Wales Television Centre Cardiff CF1 9XL The Rt Hon Lord Harlech KCMG Chairman IBA 70 Brombton Road London SW3 lEY Lord Thomson of Monifieth Chalrman Sir Brian Yours,' Director General 1)7 David Glencross ITN News Ltd ITN House 48 Wells -

Shakespeare in Production

Cambridge University Press 0521783755 - The Tempest Edited by Christine Dymkowski Frontmatter More information SHAKESPEARE IN PRODUCTION Shakespeare’s last play seems unusually elastic, capable of radically differ- ent interpretations, which reflect the social, political, scientific or moral concerns of their period. This edition of The Tempest is the first dedicated to its long and rich stage history. Drawing on a wide variety of sources, it examines four centuries of mainstream, regional and fringe productions in Britain (including Dryden and Davenant’s Restoration adaptation), nineteenth- and twentieth-century American stagings, and recent Australian, Canadian, French, Italian and Japanese productions. In a substantial, illustrated introduction Dr Dymkowski analyses the cultural significance of changes in the play’s theatrical representation: for example, when and why Caliban began to be represented by a black actor, and Ariel became a man’s role rather than a woman’s. The commentary annotates each line of the play with details about acting, setting, textual alteration and cuts, and contemporary reception. With extensive quotation from contemporary commentators and detail from unpublished promptbooks, the edition offers both an accessible account of the play’s changing meanings and a valuable resource for further research. © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521783755 - The Tempest Edited by Christine Dymkowski Frontmatter More information SHAKESPEARE IN PRODUCTION : . This series offers students and researchers the fullest possible staging of individual Shakespearean texts. In each volume a substantial intro- duction presents a conceptual overview of the play, marking out the major stages of its representation and reception. The commentary, presented alongside the New Cambridge edition of the text itself, offers detailed, line-by-line evidence for the overview presented in the introduction, making the volume a flexible tool for further research. -

Coin Hoards of Charles I and the Commonwealth of England, 1625–60, from England and Wales

COIN HOARDS OF CHARLES I AND THE COMMONWEALTH OF ENGLAND, 1625–60, FROM ENGLAND AND WALES EDWARD BESLY AND C. STEPHEN BRIGGS THE ‘English’ Civil War, fought between 1642 and 1648, gave rise to an immense number of unrecovered coin hoards, relative to any other period of British history, apart from the later third century AD. The principal purpose of this paper is to present an up-to-date inventory of these hoards, together with others that terminate with coins of Charles I or the Commonwealth of England, in succession to that published in 1987 (English Civil War Coin Hoards, henceforth ECWCH).1 The first listing of Civil War hoards was produced by Brown, who enumerated 89, subse- quently expanding this to 130 records.2 The present writer (EB), in publishing a rash of finds made in the early 1980s and with the assistance of a number of regional museum curators, took the corpus to 204 ‘Charles I’ hoards (82 of which were known only from accounts in local newspapers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries) and another nine from the Commonwealth, listed in ECWCH. Twenty-five years on, how has this picture developed? New discoveries (and the occasional ‘rediscovery’) have continued at an average rate of more than two per year, giving (to the end of 2012) an additional 59 hoards closing with Charles I which may be dated with reasonable accuracy and four from the Commonwealth period. In the meantime, the development of the internet and online availability of digitized ver- sions of journals and newspapers from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries has provided us with a new source which may be searched systematically for information which, if of limi- ted purely numismatic value, greatly expands the picture for this period – providing, as it were, a social history of English and Welsh coin finds. -

National Protest Marches of the British Unemployed in the 1920S and 1930S

MATTHIAS REISS Marching on the Capital: National Protest Marches of the British Unemployed in the 1920s and 1930s in MATTHIAS REISS (ed.), The Street as Stage: Protest Marches and Public Rallies since the Nineteenth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007) pp. 147–168 ISBN: 978 0 19 922678 8 The following PDF is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND licence. Anyone may freely read, download, distribute, and make the work available to the public in printed or electronic form provided that appropriate credit is given. However, no commercial use is allowed and the work may not be altered or transformed, or serve as the basis for a derivative work. The publication rights for this volume have formally reverted from Oxford University Press to the German Historical Institute London. All reasonable effort has been made to contact any further copyright holders in this volume. Any objections to this material being published online under open access should be addressed to the German Historical Institute London. DOI: 9 Marching on the Capital: National Protest Marches of the British Unemployed in the 1920s and 1930s MATTHIAS REISS In the 1920s and 1930s, national protest marches of the unem- ployed were becoming a British tradition. Groups of people had marched from the provinces to London to seek redress for their grievances since the Middle Ages, and the Chartists had continued this tradition in the nineteenth century. Starting in 1905, unem- ployed workers from Leicester, Nottingham, and Manchester also began to invade the capital to draw attention to their plight. In June 1913, the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies added a new dimension by organizing a 'pilgrimage' from seven- teen large cities in England and Wales to London. -

Keyworth & District Archive Material

Keyworth & District Archive Material CONTAINER DESCRIPTION The Society maintains an archive of material relating to the history of Keyworth and it's neighbouring villages. This archive is not available to the general public but requests for copies of certain items in the collection may be made to the Society's Archivist. ORIGINAL AND COPIED DOCUMENTS Arranged by subject:: Keyworth In The 1890s; Education; Employment; Keyworth Families; Law & Order; Public Administration (Parish Records); Public Utilities; Poverty/Charity Etc.; Sports, Pastimes &Amp; Entertainment; Churches In Keyworth; Transport; Drawer 1 World Wars 1 And Ii; Stanton And Its Church; Population Growth; Womens Institute; Keyworth On The Map; Inclosure Of Keyworth & Neighbouring Parishes; Nottinghamshire Directories, 1895-1941; Businesses; Neighbour Villages; Miscellaneous Items; Miscellaneous Items; Keyworth Choirs And Theatrical Groups; Keyworth Choirs And Theatrical Groups; Selby Lane School; South Wolds School; Oral History. THE ATTEWELL COLLECTION OF PHOTOGRAPHS The Attewell Collection was discovered in the attic of 8, Main Street, Keyworth, Drawer 2, (former Post Office) by Les Yallup during alterations after Mr. & Mrs. Attewell Part 1 had left. There is no date for the discovery. Few photographs have dates but several were identified in 2006 by a member of the Attewell family visiting Keyworth. ORIGINAL AND COPIED PHOTOGRAPHS Drawer 2, Arranged by subject: Part 2 Band Of Hope; Boys Brigade; Buildings; Bowls; Churches And Chapels; Football; ORIGINAL AND COPIED PHOTOGRAPHS Drawer 2, Arranged by subject: Part 3 Cricket; Events; Farming; Feignies; Fire Service; Golf; Mary Ward College; Military; Neighbouring Villages; Parish Council; People; Primary Schools. ORIGINAL AND COPIED PHOTOGRAPHS Drawer 2, Arranged by subject:: Part 4 Quorn Hunt; Tennis And Rugby; Southwold School; Sunday Schools; Transport; 1 Ve/Vj Day - 50th Anniversary; The Deborah Tomlinson Collection; Post Card Collection; Keyworth And District Local History Society.