The Meaning of Needlework to Ordinary Women

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HAND SEWING NEEDLES Quality Makes the Difference

No. 14 HAND SEWING NEEDLES Quality makes the difference. Hand sewing needles Hand sewing needles Embroidery needles Embroidery needles Sewing, embroidery and darning needles. • Sharps • Self-threading needles • Chenille • Tapestry Stitch by stitch – perfect and precise. • Betweens • Jersey needles • Crewel • Smyrna • Millinery needles Centuries of experience in metal processing, combined with Hand sewing needles: For fine embroidery we have a special needle known The higher the needle number, the finer and shorter the latest production technology available today, make Prym as a crewel needle. These slender needles with a the needle. Betweens have the same wire diameter somewhat larger eye can take one or more threads sewing, embroidery and darning needles perfect precision as the respective no. in sharps but they are approx. of stranded cotton, e.g. for white linen embroidery. Tapestry needles (with blunt point) are most tools. The needle range from Prym sets international quality 7 mm (1/4”) shorter. Both needle types are available • burr-free and finger friendly head As they correspond in length and gauge with the sharps suitable for counted thread embroidery on coarse- in packs in single sizes as well as in assorted sizes. standards – also in the variety of the assortment. Here, specialists needles, and are also easier to thread, they are often weave or even-weave fabrics. For closely woven will find their special needles. • silver or gold smooth eye facilitates used as a sewing needle. fabrics we recommend the use of sharp-pointed chenille needles. threading and avoids thread damage Sharps are our standard Both needles have large eyes which are suitable sewing needles, used to for thicker thread or wool. -

Great Lakes Region Seminar

Great Lakes Region Seminar April 11–15, 2021 Appleton, Wisconsin Hosted by the Fox Valley Embroiderers’ Guild A chapter of the Embroiderers’ Guild of America An Invitation to Vision of Stitches Vision can be defined as having the ability to see or the ability to think or plan with imagination; both definitions encompass our love of the needle arts. The Fox Valley Embroiderers’ Guild invites you to join us for Vision of Stitches, to be held at the Red Lion Hotel Paper Valley in downtown Appleton, Wisconsin, April 11–15, 2021. With inspiring faculty and classes, wonderful accommodations and food, as well as an exciting night out, we are looking forward to sharing our community with you. Of course, we will have the seminar favorites: a boutique presented by Needle Workshop of Wausau, Wisconsin, Merchandise Night and the GLR Members’ Needle Art Exhibit. We have teamed with Lions Clubs International to recycle used eyeglasses. Consider collecting used eyewear from your chapter members who are unable to join us. Looking forward to welcoming you to our Vision. Nancy Potter, Chairman, GLR Seminar, Vision of Stitches Brochure Contents Proposed Event Schedule 3 Registration Information 4 Process & Instructions Registration Fees and Class Confirmation Registrar’s Contact Information Hotel Registration 5 Seminar Cancellation Policy 5 Special Events 6 Boutique by The Needle Workshop of Wausau, Wisconsin Half-Day Classes: Sunday Meet the Teachers: Sunday Teachers’ Showcase: Monday Tuesday Night Out: Dinner at Pullmans at Trolley Square, featuring professor -

Project Description

Project Description Candlewicking is a form of surface embroidery that traditionally uses an unbleached cotton thread on a piece of unbleached muslin. It gets Candlewicking its name from the nature of the thread, which very much resembles the wick used in a candle. Motifs are created using a variety of knots (Colonial) and satin stiches (backstitich). A warm covering made of two layers of cloth filled with a material with loft and tyed together. Tying refers to the technique of using thread, Comforters yarn or ribbon to pass through all three layers of the comforter at reqular intervals. These "ties" hold the layers together during use and especially when the comforter is washed. A warm covering made of two layers of cloth filled with a material with Quilts loft and stitched together in lines or patterns. The top layer is typically pieced together and the bottom is one solid layer. Process of stitching together two layers of fabric, usually with a soft, thick substance placed between them. The layer of wool, cotton, or other stuffing provides insulation; the stitching keeps the stuffing evenly distributed and also provides opportunity for artistic expression. Quilting has long been used for clothing in many parts of the world, especially Quilting in the Far and Middle East and the Muslim regions of Africa. It reached its fullest development in the U.S., where it was at first popularly used for petticoats and comforters. By the end of the 18th century the U.S. quilt had distinctive features, such as coloured fabric sewn on the outer layers (appliqué) and stitching that echoed the appliqué pattern. -

Autumn, 2007 $P5a.G0e0 1

HILLCREEK FIBER NEWS Autumn, 2007 $P5a.g0e0 1 Carol Leigh’s Specialties HILLCREEK FIBER STUDIO Established 1982 Established 1986 Specializing in Custom Handwoven Specializing in Workshops Textiles, Nature-Dyed Fibers, in Nature-dyeing, Spinning, Handspun Yarns Knitting, and Weaving, and in using natural fibers and dyes related tools, supplies and books Carol Leigh’s Bed & Breakfast and Home of the Airport Shuttle Service from Spriggs 5 ' & 7 ’ A d j u s t a b l e St Louis & Kansas City Triangle, Square, & Rectangle HILLCREEK FIBER STUDIO available for students Frame Looms Autumn 2007, Vol XXV, No 2 Event Calendar for 2007-2008 Subscription $8.00/year for two issues Autumn Greetings, Fiber Friends! Welcome to Fall and some cooling temps! This summer’s record-breaking heat and way below normal rainfall has taken its toll on plants and energy. News-breaking announcements! There have been some major developments on the Hillcreek Fiber front. As of July 1, 2007, Hillcreek Yarn Shoppe, LLC, the knitting part of our business, has become a separate entity. Daughter Rebecca has partnered with Joan Ditmore who has purchased from us the knitting part of the business, only. Denny and I will continue Hillcreek Fiber Studio, the weaving, spinning and natural dyeing part of the business, now in its 25th year. The Yarn Shoppe will be sending out its own announcements, mostly by e-mail, so if you’d like to receive communications from them on upcoming classes, new products, and specials, let them know. Check out page 7 of this issue of Hillcreek Fiber News for further info. -

Advanced Silk Shading

ROYAL SCHOOL OF NEEDLEWORK 2019-2020 ACADEMIC YEAR DIPLOMA ADVANCED SILK SHADING Traditionally worked with silk thread on silk or linen fabric, but now more usually worked in stranded cotton thread. Silk is still the most usual background fabric but a variety of other fabrics may be used. For Advanced Silk Shading you may work EITHER an animal, bird, fish or reptile; OR a tapestry shaded human figure. SILK SHADED ANIMAL OR BIRD AIM – To demonstrate an advanced level of technical skill by working a realistic and naturally shaded embroidery of an animal, fish, reptile or bird using Long and Short Stitch with one strand of stranded cotton (or fine silk thread). To utilise shading and stitch direction to accurately depict musculature, fur, scales and clearly defined feathers as appropriate. Please note: All preparatory work (e.g. outlines, drawings, stitch plans, original source material) MUST be handed in for assessment or the work will not be marked. DESIGN Try to come with some ideas for a design and bring along some photographs. The photograph must be printed a similar size to the embroidery size otherwise it is very difficult to work. It is essential to work from a crisp, clear, well-focused photograph where you can see the individual colours and changes from dark to light. Illustrations can sometimes be harder to follow, and you should be wary of images from the Internet, which are often poor quality and may not print sufficiently well. However there are many places online from which you can purchase high quality images. The tutor will be able to make suggestions and help you bring your ideas together. -

Inside Hours Holidays

VolumeC 19, nreativeumber 2 Sewing Center Naewspril - September 2012 A NOTE TO OUR FRIENDS As the warmer than usual winter slowly slips Bernina products, the QuiltMotion Software, has been inside into springtime, we've enjoyed not having snow and a big hit with everyone. If you haven't seen this new lots of cold weather. The rain has helped our yards product, designed especially for quilters, be sure to Bernina owner Classes and the lakes are back up to normal levels, so I'm take a look! Page 2 getting the boat ready to go. The fall of this year will bring the Berry Patch our As we look forward in 2012, we are reminded 35th anniversary in business. A retail business never new Class Schedule of what a good year 2011 was for the Berry Patch. operates in a vacuum. It requires really supportive Pages 3 - 7 Our expansion of the year before has given us the and loyal customers and really loyal and competent event Calendars opportunity to add more merchandise for you and employees. We are grateful we have both. Pages 8 - 13 allowed us to spread our wings a bit. We appreciate all the kind comments about the store this year and salute Thank you for your continued support, Stayce for all her hard work in merchandising. The class schedule has lots of new classes for Bob, Shirley, Stayce and the HOURs your review and don't forget Shirley's Recipe Corner. I can personally attest to how good it is! One of our entire Berry Patch staff Monday - Saturday 10 a.m. -

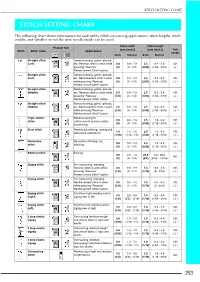

Stitch Setting Chart

STITCH SETTING CHART STITCH SETTING CHART The following chart shows information for each utility stitch concerning applications, stitch lengths, stitch widths, and whether or not the twin needle mode can be used. Stitch width Stitch length Presser foot [mm (inch.)] [mm (inch.)] Twin Stitch Stitch name Applications needle Auto. Manual Auto. Manual Straight stitch General sewing, gather, pintuck, (Left) etc. Reverse stitch is sewn while 0.0 0.0 - 7.0 2.5 0.2 - 5.0 OK pressing “Reverse/ (0) (0 - 1/4) (3/32) (1/64 - 3/16) ( J ) Reinforcement Stitch” button. Straight stitch General sewing, gather, pintuck, (Left) etc. Reinforcement stitch is sewn 0.0 0.0 - 7.0 2.5 0.2 - 5.0 OK while pressing “Reverse/ (0) (0 - 1/4) (3/32) (1/64 - 3/16) ( J ) Reinforcement Stitch” button. Straight stitch General sewing, gather, pintuck, (Middle) etc. Reverse stitch is sewn while 3.5 0.0 - 7.0 2.5 0.2 - 5.0 OK pressing “Reverse/ (1/8) (0 - 1/4) (3/32) (1/64 - 3/16) ( J ) Reinforcement Stitch” button. Straight stitch General sewing, gather, pintuck, (Middle) etc. Reinforcement stitch is sewn 3.5 0.0 - 7.0 2.5 0.2 - 5.0 OK while pressing “Reverse/ (1/8) (0 - 1/4) (3/32) (1/64 - 3/16) ( J ) Reinforcement Stitch” button. Triple stretch General sewing for 0.0 0.0 - 7.0 2.5 1.5 - 4.0 OK stitch reinforcement and decorative (0) (0 - 1/4) (3/32) (1/16 - 3/16) ( J ) topstitching Stem stitch Reinforced stitching, sewing and 1.0 1.0 - 3.0 2.5 1.0 - 4.0 OK decorative applications (1/16) (1/16 - 1/8) (3/32) (1/16 - 3/16) ( J ) Decorative Decorative stitching, top 0.0 0.0 - 7.0 2.5 1.0 - 4.0 OK stitch stitching (0) (0 - 1/4) (3/32) (1/16 - 3/16) ( J ) Basting stitch Basting 0.0 0.0 - 7.0 20.0 5.0 - 30.0 NO (0) (0 - 1/4) (3/4) (3/16 - 1-3/16) Zigzag stitch For overcasting, mending. -

PDF Download Hardanger Embroidery

HARDANGER EMBROIDERY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Donatella Ciotti | 96 pages | 03 May 2007 | Sterling Publishing Co Inc | 9781402732270 | English | New York, United States Hardanger Embroidery PDF Book Minimum monthly payments are required. Close Help Do you have a picture to add? Shipping and handling. I especially love the close-up pictures of examples of early-style Hardanger. She wore a crisp white apron UNDER her colorful daily one, so if company showed up, she could whisk off the colorful, but mussed up one and look presentable. I love the hardanger on the collar of a blouse. Email to friends Share on Facebook - opens in a new window or tab Share on Twitter - opens in a new window or tab Share on Pinterest - opens in a new window or tab. During the Renaissance , this early form of embroidery spread to Italy where it evolved into Italian Reticella and Venetian lacework. Condition see all. Hardanger kloster …. This amount is subject to change until you make payment. Ensure that the holes are facing stitches going outside; as shown in the picture above. Picture Information. If you take a shortcut and miss out a number on the diagram your stitches won't hold when you start the cutting process. Apparently wait list means go online and buy it quickly as the store does not wait for you to response to the email. Listed in category:. As you progress through the course, I introduce you to the different stitches that you need. However, that number can vary. The seller has not specified a shipping method to Germany. -

Janome 3160QDC Manual

INSTRUCTION BOOK IMPORTANT SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS This appliance is not intended for use by persons (including children) with reduced physical, sensory or mental capabilities, or lack of experience and knowledge, unless they have been given supervision or instruction concerning use of the appliance by a person responsible for their safety. Children should be supervised to ensure that they do not play with the appliance. When using an electrical appliance, basic safety precautions should always be followed, including the following: This sewing machine is designed and manufactured for household use only. Read all instructions before using this sewing machine. DANGER— To reduce the risk of electric shock: An appliance should never be left unattended when plugged in. Always unplug this sewing machine from the electric outlet immediately after using and before cleaning. WARNING— To reduce the risk of burns, fire, electric shock, or injury to persons: 1. Do not allow to be used as a toy. Close attention is necessary when this sewing machine is used by or near children. 2. Use this appliance only for its intended use as described in this owner’s manual. Use only attachments recommended by the manufacturer as contained in this owner’s manual. 3. Never operate this sewing machine if it has a damaged cord or plug, if it is not working properly, if it has been dropped or damaged, or dropped into water. Return this sewing machine to the nearest authorized dealer or service center for examination, repair, electrical or mechanical adjustment. 4. Never operate the appliance with any air opening blocked. Keep ventilation openings of this sewing machine and foot controller free from accumulation of lint, dust and loose cloth. -

Smocking, Fancy Stitches, and Cross Stitch and Darned Net Designs

The Butterick Publishing G©. Smoking Fancy Stitches VOX.. V L t 1, 3STO. H. TVT A "ST, 1895. METROPOLITAN PAMPHLET SERIES. ISSUED QUARTERLY: Subscription Price, 2s. or 50 Cents. Price per Copy, 6d. or 15 Cents. ?» MOCKING, pANCY Stitches AND Cross-Stitch and Darned Net Designs. PUBLISHED BY THE BUTTERICK PUBLISHING CO. (LIMITED), LONDON AND NGW VORtf. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year., 1895, by The Butterick Publishing Co, (Limited), in the Office of the Librarian of Congress at Washington. ENTERED AT THE POST OFFICE AT NEW YORK, N. Y., AS SECOND-CLASS MATTEP. :, Metropolitan Art Series. THE ART OF DRAWN-WORR, Standard and Modern Methods : Tie Finest and Most Reli- able Book upon Drawn-Work ever Prepared and Issued. The Complete Art, from the Drawing of the Fabric Threads to the Most Intricate Knotting of the Strands aDd Working Threads. Illustrations of Every Step of the Work assist the purchaser of this Book in Developing its Dosigns. Price, 2s. (by Post, 2s. 3d.) or SO Cents "J* HE ART OF CROCHETING: A Handsomely Dlnstrated and very valuable Book of Instructions upon the Fascinating Occupation of Crocheting, which is a Guide to the Beginner and a Treasure of New Ideas to the Expert in Crochet-Work. Every Instruction is Accurate, every Engraving a Faithful Copy of the design it represents. Price, lis. (by Post, 2s. 3d.) or BO Cents. PANCYAND PRACTICAL CROCHET-WORK: AnewMannal of Crochet-Work, elaborately illustrated and containing the following Departments : Edgings and insertions; Squares, Hexagons, Rosettes. Stars, etc, for Scarfs. Tidies, Counterpanes, Cushions, etc.; Doileys, Center-Pieces, Matts, etc.; Articles of Use and Ornament ; Pretty articles for Misses' affd Children's tTse ; Dolly's Domain ; Bead Crochet and Mould Crochet Every lady who has our pamphlet entitled The Art of Crocheting should also have " Fancy and Practical Crochet. -

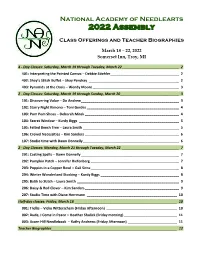

2022 Assembly

National Academy of Needlearts 2022 Assembly Class Offerings and Teacher Biographies March 18 – 22, 2022 Somerset Inn, Troy, MI 4 - Day Classes: Saturday, March 19 through Tuesday, March 22 _____________________________ 2 401: Interpreting the Painted Canvas ─ Debbie Stiehler ___________________________________ 2 402: Shay’s Stitch Buffet ─ Shay Pendray ______________________________________________ 2 403: Pyramids at the Oasis ─ Wendy Moore ____________________________________________ 3 2 - Day Classes: Saturday, March 19 through Sunday, March 20______________________________ 3 101: Discovering Value ─ Do Andrew __________________________________________________ 3 102: Starry Night Kimono ─ Toni Gerdes _______________________________________________ 4 103: Pom Pom Shoes ─ Deborah Mitek ________________________________________________ 4 104: Secret Window ─ Kurdy Biggs ___________________________________________________ 5 105: Felted Beech Tree ─ Laura Smith _________________________________________________ 5 106: Crewel Necessities ─ Kim Sanders ________________________________________________ 6 107: Studio time with Dawn Donnelly _________________________________________________ 6 2 - Day Classes: Monday, March 21 through Tuesday, March 22 _____________________________ 7 201: Casting Spells ─ Dawn Donnelly __________________________________________________ 7 202: Pumpkin Patch ─ Jennifer Riefenberg _____________________________________________ 7 203: Poppies in a Copper Bowl – Gail Sirna _____________________________________________ -

Ann's Orchard Needlework

Ann’s Orchard Needlework Tea Towel to Embroidered Cushion! with Bobble Edging TaDah! A little surface embroidery,! fold in half and stitch cushion! then crochet a bobble edging Shortly before Christmas I came across this fabulous tea towel designed by Holly Fream for Anthropologie ! and decided it was far too good for drying dishes and would make a lovely pug themed cushion for my ! daughter. So, if a similar tea towel catches your eye and you fancy transforming it read on…….. 1. Pop your tea towel in an embroidery hoop! Choose an area of the printed design you would like to embroider – you can do as much or as little as you ! like – and fit an embroidery hoop over the area to keep the fabric taut, helping to keep your stitches even. 2. Embroider the design! Use stranded embroidery cotton and a variety of stitches to add texture and shading to the printed image. For the collie and cat I simply used satin stitches and beads to enhance the eyes. For the pug I use seed ! stitches to give texture to the fur, chain stitch and French knots on the ears, satin stitch and jet black beads ! for the eyes and a row of French stitches around the outline. Threads: Pug – Charcoal Anchor 236, Grey Anchor 398, Pink DMC 3778 Cat – Lime Green Anchor 734 3. Stitch the cushion! Remove the outer stitching of the tea towel and open out the edge seams. Fold the tea towel in half with! right sides together. Stitch a seam approximately 1cm from the edge around the entire cushion leaving ! an opening of approximately 10cm on one side.