Lincoln County, Washington Hazard Mitigation Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High Resolution Adobe PDF

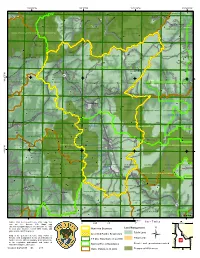

115°20'0"W 115°0'0"W 114°40'0"W 114°20'0"W PISTOL LAKE " CHINOOK MOUNTAIN ARTILLERY DOME SLIDEROCK RIDGE FALCONBERRY PEAK ROCK CREEK SHELDON PEAK Red Butte "Grouse Creek Peak WHITE GOAWTh iMte OVaUlleNyT MAoIuNntain LITTLE SOLDIER MOUNTAIN N FD " N FD 6 8 8 T d Parker Mountain 6 Greyhound Mountain r R a k i e " " 5 2 l e 0 1 0 r 0 0 il 1 C l i a 1 n r o Big Soldier Mountain a o e pi r n Morehead Mountain T Pinyon Peak L White MoSunletain g Deer Rd " T " HONEYMOON LAKE " " BIG SOLDIER MOUNTAIN SOLDIER CREEK GREYHOUND MOUNTAIN PINYON PEAK CASTO SHERMAN PEAK CHALLIS CREEK LAKES TWIN PEAKS PATS CREEK Lo FRANK CHURCH - RIVER OF NO RETURN WILDERNESS o n Sherman Peak C Mayfield Peak Corkscrew Mountain r " d e " " R ek ls R l d a Mosquito Flat Reservoir F r e Langer Peak rl g T g k a Ruffneck Peak " ac d D P R d " k R Blue Bunch Mo"untain d e M e k R ill C r e Bear Valley Mountain k e e htmile r " e ig C r E C en r C re d ave Estes Mountain e G ar B e k " R BLUE BUNCH MOUNTAIN d CAPE HORN LAKES LANGER PEAK KNAPP LAKES MOUNT JORDAN l Forest CUSTER ELEVENMILE CREEK BAYHORRSaEm sLhAorKn EMountaiBn AYHORSE Nat De Rd Keysto"ne Mountain velop Road 579 d R " Cabin Creek Peak Red Mountain rk Cape Horn MounCtaaipne Horn Lake #1 o Bay d " Bald Mountain F hors R " " e e Cr 2 d e eek 8 R " nk Rd 5 in Ya d a a nt o ou Lucky B R S A L M O N - C H A L L I S N Fo S p M y o 1 C d Bachelor Mountain R q l " u e 2 5 a e d v y 19 p R Bonanza Peak a B"ald Mountain e d e w Nf 045 D w R R N t " s H s H C d " e sf r e o Basin Butte r 0 t U ' o r e F a n e 0 l t 21 t -

Canada's Earthquakes

Document generated on 09/26/2021 12:45 p.m. Geoscience Canada Canada’s Earthquakes: ‘The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly’ J. F. Cassidy, G. C. Rogers, M. Lamontagne, S. Halchuk and J. Adams Volume 37, Number 1, January 2010 Article abstract Much of Canada is ‘earthquake country’. Tiny earthquakes (that can only be URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/geocan37_1art01 recorded by seismographs) happen every day. On average, earthquakes large enough to be felt occur every week in Canada, damaging earthquakes are years See table of contents to decades apart, and some of the world’s largest earthquakes are typically separated by intervals of centuries. In this article, we provide details on the most significant earthquakes that have been recorded in, or near, Canada, Publisher(s) including where and when they occurred, how they were felt, and the effects of those earthquakes. We also provide a brief review of how earthquakes are The Geological Association of Canada monitored across Canada and some recent earthquake hazard research. It is the results of this monitoring and research, which provide knowledge on ISSN earthquake hazard, that are incorporated into the National Building Code of Canada. This, in turn, will contribute to reduced property losses from future 0315-0941 (print) earthquakes across Canada. 1911-4850 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Cassidy, J. F., Rogers, G. C., Lamontagne, M., Halchuk, S. & Adams, J. (2010). Canada’s Earthquakes:: ‘The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly’. Geoscience Canada, 37(1), 1–16. All rights reserved © The Geological Association of Canada, 2010 This document is protected by copyright law. -

1:100,000 1 Inch = 1.6 Miles Central Idaho-01

R 10 E R 11 E 115°7'30"W R 12 E 115°W R 13 E 114°52'30"W R 14 E 114°45'W R 15 E 114°37'30"W R 16 E 114°30'W R 17 E 114°22'30"W R 18 E S k i k e l v e Joe Jump Basin e Lookout Mountain k La e e r st e r r k C k e R C e h ee r C e e Little a Cr u Iron Cre k nce C l h r w Airport Rd e Car c C Central Idaho-01 e bo n an k B liv o t C nat e l e d e r u k i a r C e a g l C e F S r r e e e e S e C a M M C k e t s r a k o in a C a G o Creek s th rc in k i o m o e C Fire Suppression Constraints e S re C r k y e r k e e C m re e ek n m C e k i r r Alpine Peak o Ziegler Basin t Fish Critical Habitats T 10 N a C Observation Peak J e an s B g je T 10 N n d i Jimmy Smith Lake n v i ulch Bull Trout Critical Habitat a G r Hoodoo Lake L k rry k Creek ake Cree he G Big L Big Lake Creek 222 e Lake C Grandjean e Big Balsam Rd r k Trailer Lakes Regan, Mount C e Spawning Areas of Concern Little Redfish Lake e ry r S a C ek 222 F re Trail Creek Lakes d o o C n c rk l u r Resource Avoidance Area 36 P i 36 o a ra Big Lake Creek a Williams Peak B M ye T NF-214 Rd tte 31 31 36 31 31 36 31 Ri Cleveland Creek Safety Concerns ve 36 Wapiti Creek Rd r EAST FORK 36 S a l Suppression tactics Avoidance Area 01 Thompson Peak m o Railroad Ridge n Crater Lake 06 01 R Bluett Creek D Misc Resource Areas i ry 06 01 k v 01 01 06 06 Gu 01 06 k e e lc e re h e C r k r k k e Meadows, The C e oo re Watson Peak im Creek x Wilderness Area e hh C Iron Basin J o r Fis old Chinese Wall ek F C G re ti C Bluett Creek i Slate Creek r Retardant Avoidance Area p Gunsight Lake e a ld W ou B -

Fragility Functions of Manufactured Houses Under Earthquake Loads

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Civil and Environmental Engineering Theses, Dissertations, and Student Research Civil and Environmental Engineering 7-2021 Fragility Functions of Manufactured Houses under Earthquake Loads Shuyah Tani Aurore Ouoba University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/civilengdiss Part of the Civil Engineering Commons, Other Civil and Environmental Engineering Commons, and the Structural Engineering Commons Ouoba, Shuyah Tani Aurore, "Fragility Functions of Manufactured Houses under Earthquake Loads" (2021). Civil and Environmental Engineering Theses, Dissertations, and Student Research. 170. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/civilengdiss/170 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Civil and Environmental Engineering at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Civil and Environmental Engineering Theses, Dissertations, and Student Research by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. FRAGILITY FUNCTIONS OF MANUFACTURED HOUSES UNDER EARTHQUAKE LOADS by Shuyah T. A. Ouoba A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Major: Civil Engineering Under the Supervision of Professor Christine E. Wittich Lincoln, Nebraska July, 2021 FRAGILITY FUNCTIONS OF MANUFACTURED HOUSES UNDER EARTHQUAKE LOADS Shuyah T. A. Ouoba, M.S University of Nebraska, 2021 Advisor: Christine E. Wittich Manufactured homes are factory-built homes made of wooden structural members, then transported and installed on a given site. Manufactured housing is used in many countries, such as in Australia, and in New Zealand but remain mostly popular in the United States. -

Engineering Geology in Washington, Volume I Washington Diviaion of Geology and Euth Resources Bulletin 78

ENGINEERING GEOLOGY IN WASHINGTON Volume I RICHARD W. GALSTER, Chairman Centennial Volume Committee Washington State Section, Association of Engineering Geologists WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES BULLETIN 78 1989 Prepared in cooperation with the Washington State Section of the A~ociation or Engineering Geologists ''WNatural ASHINGTON STATE Resources DEPARTMENT OF Brian Boyle • Commlssloner 01 Public Lands Ari Stearns - Sup,,rvuor Division of Geology and Earth Resources Raymond LcumanJs. Slate Geologist The use of brand or trade names in this publication is for pur poses of identification only and does not constitute endorsement by the Washington Division of Geology and Earth Resources or the Association of Engineering Geologists. This report is for sale (as the set of two volumes only) by: Publications Washington Department of Natural Resources Division of Geology and Earth Resources Mail Stop PY-12 Olympia, WA 98504 Price $ 27.83 Tax 2.17 Total $ 30.00 Mail orders must be prepaid; please add $1.00 to each order for postage and handling. Make checks or money orders payable to the Department of Natural Resources. This publication is printed on acid-free paper. Printed in the United States of America. ii VOLUME I DEDICATION . ................ .. .. ...... ............ .......................... X FOREWORD ........... .. ............ ................... ..... ................. xii LIST OF AUTHORS ............................................................. xiv INTRODUCTION Engineering Geology in Washington: Introduction Richard W. Galster, Howard A. Coombs, and Howard H. Waldron ................... 3 PART I: ENGINEERING GEOLOGY AND ITS PRACTICE IN WASHINGTON Geologic Factors Affecting Engineered Facilities Richard W. Galster, Chapter Editor Geologic Factors Affecting Engineered Facilities: Introduction Richard W. Galster ................. ... ...................................... 17 Geotechnical Properties of Geologic Materials Jon W. Koloski, Sigmund D. Schwarz, and Donald W. -

Geological Investigation of the Railroad Ridge Diamicton, White Cloud Peaks Area, Idaho. Susan L

Lehigh University Lehigh Preserve Theses and Dissertations 1-1-1983 Geological investigation of the Railroad Ridge diamicton, White Cloud Peaks area, Idaho. Susan L. Gawarecki Follow this and additional works at: http://preserve.lehigh.edu/etd Part of the Geology Commons Recommended Citation Gawarecki, Susan L., "Geological investigation of the Railroad Ridge diamicton, White Cloud Peaks area, Idaho." (1983). Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2426. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION OF THE RAILROAD RIDGE DIAMICTON, WHITE CLOUD PEAKS AREA, IDAHO by Susan L. Gawarecki A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Committee of Lehigh University in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Science in Geological Sciences Lehigh University 1983 ProQuest Number: EP76702 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest EP76702 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 This thesis is accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science. -

The Field Act and Its Effectiveness in Reducing Earthquake Damage

State of California Alfred E. Alquist Seismic Safety Commission The Field Act and its Relative Effectiveness in Reducing Earthquake Damage in California Public Schools Appendices October 2009 1755 Creekside Oaks Drive, #100 Sacramento, California 95833 (916) 263-5506 www.seismic.ca.gov CSSC 09-02 i Table of Contents Page Appendix A: Synopsis of Research Methodology 1 Appendix B: Major 20th Century California Earthquakes 4 Appendix C: Counties that were Affected by California Earthquakes 5 Appendix D: School Sites that Experienced MMI VII or Greater Ground Shaking 6 Appendix E: Mapping of School Sites on Google Earth and Google Maps 18 Appendix F: History of Significant Building Code Changes 21 Appendix G: Comparison of Administrative Requirements of the Uniform 34 Building Code and the Field Act Appendix H: Performance of Field Act Structures as Compared to Non-Field 35 Act Structures in Significant California Earthquakes Since 1933 Appendix I: Description of the Modified Mercalli Intensity (MMI) Scale 45 Appendix J: ATC-20 Building Rating System 47 Appendix K: Significant U.S. Earthquakes Since 1933 Outside California 48 Appendix L: American Red Cross Designated Shelters in 23 California Counties 53 Appendix M: Bibliography of Literature Related to the Field Act 54 References 55 ii Appendix A: Synopsis of Research Methodology The objective of this study was to determine if the Field Act has been effective in reducing structural damage in public school buildings, including community colleges, as compared to comparable buildings constructed to non-Field Act standards. This effort was based on literature that has already been published; no primary data collection was intended to be part of this study. -

Seismic Intensities of Earthquakes of Conterminous United States Their Prediction and Interpretation

Seismic Intensities of Earthquakes of Conterminous United States Their Prediction and InterpretationJL Seismic Intensities of Earthquakes of Conterminous United States Their Prediction and Interpretation By J. F. EVERNDEN, W. M. KOHLER, and G. D. CLOW GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1223 Description of a model for computing intensity patterns for earthquakes. Demonstration and explanation of systematic variations of attenuation and earthquake parameters throughout the conterminous United States UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASH INGTON: 1981 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR JAMES G. WATT, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Doyle G. Frederick, Acting Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 81-600089 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 CONTENTS Page Page Abstract ___________________________ ___ 1 Examples of observed predicted intensities Con. Introduction __ ____________________ 1 Seattle earthquake of April 13, 1949 ____________ 23 Rossi-Forel intensities versus Modified Mercalli intensities __ 2 Lompoc earthquake of November 4, 1927 __________ 27 Presently available models for predicting seismic intensities __ 3 Earthquakes of Eastern United States _ _______ _ 36 California ___________________________ 3 Fault length versus moment, magnitude, and energy release Conterminous United States _______________ 4 versus k region._______________________ 36 Examples of observed versus predicted intensities____ ___ 7 Crustal calibration as function of region __ -

Significant Earthquakes Experienced in Washington Since 1872 Note: Top 6 Earthquakes with Greatest Impacts Are Preceded by ** and Underlined

Significant Earthquakes Experienced in Washington Since 1872 Note: Top 6 earthquakes with greatest impacts are preceded by ** and underlined 1800s **December 14, 1872 Washington State Earthquake The earthquake is the largest historical earthquake in eastern Washington, and the most widely felt earthquake in the state. The magnitude of the shallow earthquake, centered around Lake Chelan, WA, is debated. It was an estimated M 6.5 to M 7.5, with a moment intensity (MI) of 6.8. The maximum modified Mercalli intensity was IX. It was felt over 390,000 mi2. Landslides and groundwater disturbances occurred near the lake and along the Columbia River, and a fissure split in the ground south of Seattle. Damages included chimney cracks and shattered windows. People were knocked off their feet at Snoqualmie Pass, and trees toppled. The failed Spencer Canyon fault was discovered long after the earthquake. Sources: https://assets.pnsn.org/HIST_CAT/SSA01274.pdf https://web.archive.org/web/20160101023203/https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle- news/scientists-may-be-cracking-mystery-of-big-1872-earthquake/ http://www.burkemuseum.org/static/earthquakes/cur-history.html December 12, 1880 Earthquake The earthquake originating near Kent, WA has no recorded magnitude, but was felt from Victoria to Portland. It had a maximum modified Mercalli intensity of VII. Shaking caused ringing of bells, chimney damage. Source: https://assets.pnsn.org/CASCAT2006/Index_152_216.html April 30, 1882 Earthquake Originating in the Puget Sound - Salish Sea area, the deep earthquake was estimated to be M 5.75 to M 6.2. Modified Mercalli intensity reported in Olympia was VI. -

Normalized Earthquake Damage and Fatalities in the United States: 1900–2005

Normalized Earthquake Damage and Fatalities in the United States: 1900–2005 Kevin Vranes1 and Roger Pielke Jr.2 Abstract: Damage estimates from 80 U.S. earthquakes since 1900 are “normalized” to 2005 dollars by adjusting for inflation, increases in wealth, and changes in population. Factors accounting for mitigation at 1 and 2% loss reduction per year are also considered. The earthquake damage record is incomplete, perhaps by up to 25% of total events that cause damage, but all of the most damaging events are accounted for. For events with damage estimates, cumulative normalized losses since 1900 total $453 billion, or $235 billion and $143 billion when 1 and 2% mitigation is factored, respectively. The 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire adjusts to $39–$328 billion depending on assumptions and mitigation factors used, likely the most costly natural disaster in U.S. history in normalized 2005 values. Since 1900, 13 events would have caused $1 billion or more in losses had they occurred in 2005; five events adjust to more than $10 billion in damages. Annual average losses range from $1.3 billion to $5.7 billion with an average across data sets and calculation methods of $2.5 billion, below catastrophe model estimates and estimates of average annual losses from hurricanes. Fatalities are adjusted for population increase and mitigation, with five events causing over 100 fatalities when mitigation is not considered, four ͑three͒ events when 1% ͑2%͒ mitigation is considered. Fatalities in the 1906 San Francisco event adjusts from 3,000 to over 24,000, or 8,900 ͑3,300͒ if 1% ͑2%͒ mitigation is considered. -

Wood River Area

Trail Report for the Sawtooth NRA **Early season expect snow above 8,000 feet high, high creek crossings and possible downed trees** Due to Covid 19 please be aware of closures, limits to number of people, and as always use leave no trace practices Wood River Area Maintained in Date Name Trail # Trail Segment Difficulty Distance Wilderness Area Hike, Bike, Motorized Description/Regulations Conditions, Hazards and General Notes on Trails 2020 Multi-use trail for hikers and bikers going from Sawtooth NRA to Galena 6/11/2020 Volunteers Harriman Easy 18 miles Hike and Bike Lodge; Interpretive signs along the trail; can be accessed along Hwy 75. Mountain Biked 9 miles up the trail. Easy- Hemingway-Boulders Hike, Bike only the 1st Wheelchair accessible for the first mile. Bicycles only allowed for the first 6/25/2020 210 Murdock Creek Moderate 7 miles RT Wilderness mile mile and then it becomes non-motorized in the wilderness area. Trail clear except for a few easily passible downed trees Hemingway-Boulders 127 East Fork North Fork Moderate 7 miles RT Wilderness Hike Moderate-rough road to trailhead. Hemingway-Boulders Drive to the end of the North Fork Road, hikes along the creak and 128 North Fork to Glassford Peak Moderate 4.5 Wilderness Hike through the trees, can go to West Pass or North Fork. North Fork Big Wood River/ West Moderate- Hemingway-Boulders Hike up to West Pass and connects with West Pass Creek on the East Fork Fallen tree suspended across trail is serious obstacle for horses one third mile 6/7/2020 Volunteers 115 Pass Difficult 6.3 Wilderness Hike of the Salmon River Road. -

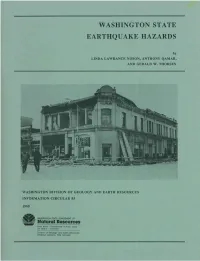

Information Circular 85. Washington State Earthquake Hazards

WASHING1rON STATE EARTHQUAKE:HAZARDS by LINDA LAWRANCE NOS , ANTHONY QAMAR, AND GERALD W. THORSEN WASHING TON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCE INFORMATION CIRCULAR 85 1988 WASHINGTON STATE DEPARTMENT OF Natural Resources Brian Boyle - Commissioner of Public Lands Art Stearns - Supervisor Division of Geology and Earth Resources Raymond Lasmanis, State Geologist Cover photo: Damage to an unreinforced masonry building in downtown Centralia in 1949. A man was killed by the falling upper walls of this two-story corner building. Unreinforced masonry walls, gables, cornices, and partitions were the most seriously damaged structures in the 1949 and 1965 earthquakes. Inferior mortar and inadequate ties between walls and floors compounded the damage. (Photo from the A. E. Miller Col lection, University of Washington Archives) -- WASHING TON ST ATE EARTHQUAKE HAZARDS by LINDA LAWRANCE NOSON, ANTHONY QAMAR, AND GERALD W. THORSEN WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES INFORMATION CIRCULAR 85 1988 • . ' NaturalWASHING10N STATE Resources DEPARTMENT OF Brtan Boyle • Commasloner 01 P\lbllc Lands Art Steorns • Supervisor Divisfon 0 1 Geology and Earth Resources Raymond Lasmanis. State Geo!ogisl The authors gratefully acknowledge review of the manuscript of this publication by members of the Geophysics Program. University of Washington. This report is available from: Publications Washington Department of N arural Resources Division of Geology and Earth Resources Mail Stop PY-12 Olympia, WA 98504 The printing of this report was supported by U.S. Geological Survey Earthquake Hazards Reduction Program Agreement No. 14-08-0001-A0509. This publication is free, but please add $1.00 to each order for postage and handling. Make checks or money orders payable to the Department of Natural Resources.