Papel Picado /Cut Paper Banners

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Observations on the Nature of Papyrus Bonding

]. Ethnobiol. 11(2):193-202 Winter 1991 SOME OBSERVATIONS ON THE NATURE OF PAPYRUS BONDING PETER E. SCORA Moreno Valley, CA 92360 and RAINER W. SCORA Department of Botany and Plant Sciences University of California Riverside, CA 92521 ABSTRACT.-Papyrus (Cyperus papyrus, Cyperaceae) was a multi-use plant in ancient Egypt. Its main use, however, was for the production of laminated leaves which served as writing material in the Mediterranean world for almost 5000 years. Being a royal monopoly, the manufacturing process was kept secret. PI~us Secundus, who first described this process, is unclear as to the adhesive forces bonding the individual papyrus strips together. Various authors of the past century advanced their own interpretation on bonding. The present authors believe that the natural juices of the papyrus strip are sufficient to bond the individual strips into a sheet, and that any additional paste used was for the sole purpose of pasting the individual dried papyrus sheets into a scroll. RESUMEN.-EI papiro (Cyperus papyrus, Cyperaceae) fue una planta de uso multiple en el antiguo Egipto. Su uso principal era la produccion de hojas lami nadas que sirvieron como material de escritura en el mundo meditarraneo durante casi 5000 anos. Siendo un monopolio real, el proceso de manufactura se mantema en secreto. Plinius Secundus, quien describio este proceso por primera vez, no deja claro que fuerzas adhesivas mantenlan unidas las tiras individuales de papiro. Diversos autores del siglo pasado propusieron sus propias interpretaciones respecto a la adhesion. Consideramos que los jugos naturales de las tiras de papiro son suficientes para adherir las tiras individuales y formar una hoja, y que cual quier pegamento adicional se usa unicamente para unir las hojas secas individuales para formar un rollo. -

Día De Los Muertos K-12 Educator’S Guide

Día de los Muertos K-12 Educator’s Guide Produced by the University of New Mexico Latin American & Iberian Institute Latin American & Iberian Institute Because of the geographic location and unique cultural history of New Mexico, the University of New Mexico (UNM) has emphasized Latin American Studies since the early 1930s. In 1979, the Latin American & Iberian Institute (LAII) was founded to coordinate Latin American programs on campus. Designated a National Resource Center (NRC) by the U.S. Department of Education, the LAII offers academic degrees, supports research, provides development opportunities for faculty, and coordinates an outreach program that reaches diverse constituents. In addition to the Latin American Studies (LAS) degrees offered, the LAII supports Latin American studies in departments and professional schools across campus by awarding stu- dent fellowships and providing funds for faculty and curriculum development. The LAII’s mission is to create a stimulating environment for the production and dissemination of knowl- edge of Latin America and Iberia at UNM. We believe our goals are best pursued by efforts to build upon the insights of more than one academic discipline. In this respect, we offer interdisciplinary resources as part of our effort to work closely with the K-12 community to help integrate Latin American content mate- rials into New Mexico classrooms across grade levels and subject areas. We’re always glad to work with teachers to develop resources specific to their classrooms and students. To discuss this option, or for more comprehensive information about the LAII and its K-12 resources, contact: University of New Mexico Latin American & Iberian Institute 801 Yale Boulevard NE MSC02 1690 1 University of New Mexico Albuquerque, NM 87131 Phone: (505) 277-2961 Fax: (505) 277-5989 Email: [email protected] Web: http://laii.unm.edu *Images: Cover photograph of calavera provided courtesy of Reid Rosenberg, reprinted here under CC ©. -

Leafing Through History

Leafing Through History Leafing Through History Several divisions of the Missouri Botanical Garden shared their expertise and collections for this exhibition: the William L. Brown Center, the Herbarium, the EarthWays Center, Horticulture and the William T. Kemper Center for Home Gardening, Education and Tower Grove House, and the Peter H. Raven Library. Grateful thanks to Nancy and Kenneth Kranzberg for their support of the exhibition and this publication. Special acknowledgments to lenders and collaborators James Lucas, Michael Powell, Megan Singleton, Mimi Phelan of Midland Paper, Packaging + Supplies, Dr. Shirley Graham, Greg Johnson of Johnson Paper, and the Campbell House Museum for their contributions to the exhibition. Many thanks to the artists who have shared their work with the exhibition. Especial thanks to Virginia Harold for the photography and Studiopowell for the design of this publication. This publication was printed by Advertisers Printing, one of only 50 U.S. printing companies to have earned SGP (Sustainability Green Partner) Certification, the industry standard for sustainability performance. Copyright © 2019 Missouri Botanical Garden 2 James Lucas Michael Powell Megan Singleton with Beth Johnson Shuki Kato Robert Lang Cekouat Léon Catherine Liu Isabella Myers Shoko Nakamura Nguyen Quyet Tien Jon Tucker Rob Snyder Curated by Nezka Pfeifer Museum Curator Stephen and Peter Sachs Museum Missouri Botanical Garden Inside Cover: Acapulco Gold rolling papers Hemp paper 1972 Collection of the William L. Brown Center [WLBC00199] Previous Page: Bactrian Camel James Lucas 2017 Courtesy of the artist Evans Gallery Installation view 4 Plants comprise 90% of what we use or make on a daily basis, and yet, we overlook them or take them for granted regularly. -

The Palmyrene Prosopography

THE PALMYRENE PROSOPOGRAPHY by Palmira Piersimoni University College London Thesis submitted for the Higher Degree of Doctor of Philosophy London 1995 C II. TRIBES, CLANS AND FAMILIES (i. t. II. TRIBES, CLANS AND FAMILIES The problem of the social structure at Palmyra has already been met by many authors who have focused their interest mainly to the study of the tribal organisation'. In dealing with this subject, it comes natural to attempt a distinction amongst the so-called tribes or family groups, for they are so well and widely attested. On the other hand, as shall be seen, it is not easy to define exactly what a tribe or a clan meant in terms of structure and size and which are the limits to take into account in trying to distinguish them. At the heart of Palmyrene social organisation we find not only individuals or families but tribes or groups of families, in any case groups linked by a common (true or presumed) ancestry. The Palmyrene language expresses the main gentilic grouping with phd2, for which the Greek corresponding word is ØuAi in the bilingual texts. The most common Palmyrene formula is: dynwpbd biiyx... 'who is from the tribe of', where sometimes the word phd is omitted. Usually, the term bny introduces the name of a tribe that either refers to a common ancestor or represents a guild as the Ben Komarê, lit. 'the Sons of the priest' and the Benê Zimrâ, 'the sons of the cantors' 3 , according to a well-established Semitic tradition of attaching the guilds' names to an ancestor, so that we have the corporations of pastoral nomads, musicians, smiths, etc. -

Discussion on the Shaping Arrangement of Majolica Tile with the Paper-Cut Creation Mode

Original paper Original Articles [13] Newman, D., Defensive Space: People and Design in Received Nov 20 2017; Accepted Jan 24 2018 the Violent City, London, Architectural Press, 1972. [14] Cozens, P., Saville, G., and Hillier, D., Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED): DISCUSSION ON THE SHAPING ARRANGEMENT OF A review of Modern Bibiography, Proper Management 23 (5) 328 – 356, 2005 MAJOLICA TILE WITH THE PAPER-CUT [15] Thorpe, A., Gamman, L., Design with society: Why CREATION MODE Social Responsive Design is Good Enough, CoDesign (3-4), 217 – 230, 2011. [16] Villalta, C., El Miedo al Delito en Mexico, Estrutura Yu-Ya WANG *, Chi-Shyong TZENG **, Akiyo KOBAYASHI *** Logica, Bases Emocionales y Recomendaciones Iniciales de Politica Publica, Gestion Politica, Vol XIX, * Graduate School of Design, National Yunlin University of Science and Technology, Taiwan Num 1, CIDE, Mexico, 2009. * * Graduate School of Design, National Yunlin University of Science and Technology, Taiwan [17] Kessler, El Sentimiento de Inseguridad, Sociologia del * * * Department of Science of Design, Musashino Art University, Japan Temor al Delito, Siglo XXI, Argentina,35, 2009. [18] Jasso, C., Percepcion de Inseguridad en Mexico, Revista Mexicana de Opinion Publica 15-19, 2013. Abstract: The purpose of the study is to achieve the shaping design with repetitive, symmetric, and [19] INEGI., Encuesta Nacional de Victimización y continuous graphs through papercutting. The researchers used the folding and cutting model of Percepción sobre Seguridad Pública 2016, Mexico, papercutting to build the linkage with the graphic shaping arrangement of the Majolica tile in order to 2016. discover an effective and expeditious design method for the public. -

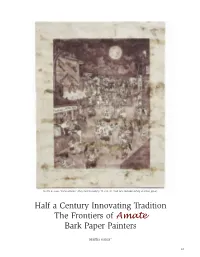

Half a Century Innovating Tradition the Frontiers of Amate Bark Paper Painters

Nicolás de Jesús, “Comierdalismo” (Shitty Commercialism), 75 x 60 cm, 1993 (line and color etching on amate paper). Half a Century Innovating Tradition The Frontiers of Amate Bark Paper Painters Martha García* 41 fter almost 50 years of creating the famous paintings on amate bark paper, Nahua artists have been given yet another well-deserved award for the tradition they have zealously pre- A served from the beginning: the 2007 National Prize for Science and the Arts in the cate- gory of folk arts and traditions. One of the most important characteristics of the continuity of their work has been the innovations they have introduced without abandoning their roots. This has allowed them to enter into the twenty-first century with themes alluding to the day-to-day life of society, like migration, touched on by the work of Tito Rutilo, Nicolás de Jesús, Marcial Camilo and Roberto Mauricio, shown on these pages. In general the Nahua painters of the Alto Balsas in Guerrero state have accustomed the assidu- ous consumer to their colorful “sheets” —as they call the pieces of amate paper— to classic scenes of religious festivities, customs and peasant life that are called “histories”. The other kind of sheet is the “birds and flowers” variety with stylized animals and plants or reproductions of Nahua myths. In part, the national prize given to the Nahua painters and shared by artists who work in lacquer and lead is one more encouragement added to other prizes awarded individually and collectively both in Mexico and abroad. As one of the great legacies of this ancient town, located in the Balsas region for more than a millennium, the communities’ paintings have become a window through which to talk to the world about their profound past and their stirring contemporary experiences. -

Welcome to Arrowmont 3

WELCOME TO ARROWMONT 3 “Te most regretful people on earth are those who felt the call to creative work… and gave to it neither the power nor time.” Mary Oliver IMPORTANT DATES AT A GLANCE Whether for you it is creative work or creative play, if you will make the time, Arrowmont will provide the place, the opportunity, and the encouragement. ARTISTS-IN-RESIDENCE Arrowmont’s commitment to education and appreciation of crafts is built upon its APPLICATION DEADLINE heritage as a settlement school founded by Pi Beta Phi in 1912. Our 13 acre campus February 1, 2017 has six buildings on the National Register of Historic Places, well-equipped studios, and places for contemplation and conversation. We appreciate being described as a EARLY REGISTRATION DEADLINE “hidden jewel” and a “neighbor” of Great Smoky Mountains National Park. REGISTRATION FEE OF $50 IS WAIVED FOR EARLY REGISTRATION Here, you will spend time immersed in the studio, you will also eat well, have the February 1, 2017 opportunity to enjoy our library, and be inspired by our galleries. EDUCATIONAL Each week a new creative community forms. Students do more than participate in this ASSISTANTS PROGRAM community, they often develop lifelong relationships. Teir shared experiences of refecting, APPLICATION DEADLINE problem solving and making creates the community. Workshops are taught by some March 1, 2017 of the fnest artists from around the world — it is their commitment to sharing their SCHOLARSHIP APPLICATION knowledge and their experiences that makes them great teachers. Tey recognize that DEADLINE there is always more to learn, and that the environment of small groups of students, March 1, 2017 engaged in experimenting and discovering together, is both inspiring and energizing. -

Día De Los Muertos Teacher Workshop

Día de los Muertos Teacher Workshop Fall 2012 K-12 Curriculum Resource Guide developed and presented by the Stone Center for Latin American Studies, Tulane University THE DAY OF THE DEAD by Margarita Vargas-Betancourt I. Introduction • Mexicans believe that during the day of the dead, the dead come back to visit their beloved who still live. • It is a time of great festivity and reunion, rather than mournful lamentation. II. The roots A. European roots • Catholic celebration of All Saints • Medieval dances of death: staging of devils and angels fighting for the souls of the dead. Death is represented as a fearful lady (sandglass, scythe, cart) B. Pre-Columbian roots • Cyclic time: dry season/ rainy season, death/life • Agricultural celebrations: day of the dead coincides with the beginning of harvest • Aztec celebrations to the dead III. The offering: la ofrenda • Purpose: 1. To honor and welcome them. 2. To make them know that they have not been forgotten in death. 3. To remind them of the sweetness of life that they once enjoyed. • Elements: 1. It is done on a table that has a colorful tablecloth (purple, orange, white) 2. Photographs of the deceased are placed in a central location 3. Copan incense 4. Cempasuchil (yellow marigold flowers) and terciopelo (a purplish-dark pink flower that looks like velvet). 5. Water: it is believed that the souls arrive thirsty from their long trip, and that they drink the water from the glass that we offered them. Thus, it is believed that as the night progresses the level of water in a glass placed on the ofrenda sinks too quickly to be by evaporation. -

Public Art in the Market

PIKE PLACE POCKET GUIDE PUBLIC ART IN THE MARKET OUR COMMUNITY Pike Place Market has a long history of attracting and inspiring artists of all mediums and styles. It has been depicted countless times over the years, capturing its Victor Steinbrueck/Native Park Plaza beautiful scenery, quirky spirit, lively vibe (and even the Billie the 11 Piggy Bank Pavilion downtrodden periods), preserving moments of history through their works of art. 6 • Mark Tobey (1890-1976) was an internationally North Arcade Crafts Market 12 First & recognized painter and a founder of the art Virginia Champion Bldg. Bldg. movement known as the Northwest School. He Urban Soames- sketched the Market in the late 1930s and '40s, Garden Pike Street Dunn Bldg. Hillclimb 8 5 7 10 documenting produce, storefronts, people and Main Arcade Stewart Garden 4 House general scenes in oil, gouache and tempera. Center LaSalle Bldg. Bldg. 9 3 Triangle Bldg. Livingston- Baker 2 Bldgs. • Architect Victor Steinbrueck (1911-85) led a Sanitary Smith Bldg. Market First & Pine Jones Bldg. grassroots campaign that helped save Pike Place Corner Bldg. Alaska 1 Market Trade Bldg. Market from the urban renewal wrecking ball. His Inn at the Fairmount Bldg. Market Bldg. book, , is filled with detailed Economy Market Market Sketchbook pen and ink drawings of everything from ramps and signage to shoppers and diners. Other creatives and bohemian characters have long been a part of the fabric and texture of the Market. EXPLORE PUBLIC ART WHILE YOU SHOP Beat artist Jack Kershaw in the '60s, Billy King from the '70s to today, and current local collector Buddy There’s a treasure trove of public artworks found throughout Foley are but a few of the many personalities that bring the Market. -

Palabras Ancladas. Fragmentos De Una Historia (Universal) Del Libro

Edgardo Civallero Palabras ancladas Palabras ancladas Fragmentos de una historia (universal) del libro Edgardo Civallero Versiones resumidas de los textos aquí incluidos fueron publicadas, como entradas de una columna bimestral titulada Palabras ancladas , en la revista Fuentes. Revista de la Biblioteca y Archivo Histórico de la Asamblea Legislativa Plurinacional de Bolivia entre septiembre de 2016 y diciembre de 2017. © Edgardo Civallero, 2018. Distribuido como pre-print bajo licencia Creative Commons by-nc-nd 4.0 "Bibliotecario". http://biblio-tecario.blogspot.com.es/ En el museo arqueológico con mi iPhone 5.2 fotografío una tablilla sumeria. Dentro de dos años y medio estará obsoleto. En veinticinco todos sus contenidos serán irrecuperables y su memoria se borrará. Miro la tablilla de barro con sus hermosos caracteres cuneiformes, dentro de otros tres mil quinientos años, seguirá, por encima de lo efímero y lo mortal, guardando la eternidad. Antonio Orihuela. "El aroma del barro". De La Guerra Tranquila (Cádiz: Origami, 2014). [01] Palabras ancladas, palabras cautivas La historia del libro —o, mejor dicho, la historia de los documentos escritos, tengan el formato que tengan— es un relato fragmentario y parcheado, cosido aquí, remendado allá, agujereado acullá. Los saltos y las lagunas son más abundantes que los hechos confirmados, y la secuencia cronológica de estos últimos tiene una fuerte tendencia a deshacerse, a perderse por senderos que no llevan a ningún sitio. Y aún así, a pesar de tratarse de un cuento bastante incierto, esa narrativa de cómo las palabras quedaron ancladas —amarradas para siempre a la arcilla, a la seda, al papiro, al pergamino o al papel— compone una parte importante de nuestra historia como sociedades y de nuestra identidad como seres humanos. -

Ficus (Fig Tree) Species of Guatemala Nicholas M

Economic Potential for Amate Trees Ficus (Fig Tree) Species of Guatemala Nicholas M. Hellmuth Introduction Entire monographs have been written on the bark paper of the Maya and Aztec codices (Van Hagen 1944). And there are plenty of scholarly botanical studies of Ficus trees of the family Moraceae. But on the Internet there is usually total confusion in popular web sites about the differences between strangler figs and normal fig trees. It is unclear to which degree the bark paper comes from a strangler fig tree, or also from anotherFicus species which is a normal tree (not dedicated to wrapping its roots around a host tree). But all this needs further research since 90% of the books and about 99% of the articles are on bark paper of Mexico. Indeed bark paper is still made in several parts of Mexico (to sell the tourists interested in Aztec, Maya and other cultures). Since we are in the middle of projects studying flavorings for cacao, Aztec and Maya ingredients for tobacco (more than just tobacco), colorants from local plants to dye native cotton clothing, and also trying to locate all the hundreds of medicinal plants of Guatemala, it would require funding to track down and study every species of Ficus. But since we are interested in all utilitarian plants of Mesoamerica, we wanted at least to prepare an introductory tabulation and a brief bibliography to assist people to understand that • strangler figs strangle other trees; these are very common in Guatemala • But there are many fig trees which are not stranglers • Figs for candy and cookies come from fig trees of other parts of the world • Not all bark paper comes just from amate (Ficus) trees For photographs we show in this first edition only the two fig trees which we have found in the last two months of field trips. -

Amate Bark Paintings Amate Is a Type of Pounded Bark Paper That Has Been Manufactured in Mexico, Since at Least 75 CE (Formerly AD)

04737 Fuller Road, East Jordan, MI 49727 (231) 536-3369 |www.miravenhill.org [email protected] Raven Hill Discovery Center is a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt corporation. Mission: Raven Hill provides a place that enhances hands-on and lifelong learning for all ages by connecting science, history & the arts. Amate Bark Paintings Amate is a type of pounded bark paper that has been manufactured in Mexico, since at least 75 CE (formerly AD). It is similar to the development of rice paper in China and papyrus in Egypt. The Otomi people began producing the paper commercially in the mid-1900’s and selling it in cities such as Mexico City, where the paper was revived by Nahua painters to create a "new" indigenous craft. Nahua paintings of the paper, which is also called "amate," are well-known. To make an Amate Bark Painting you will need a paper lunch sack or other light-weight brown paper bag, colored markers, black marker, paraffin wax (a candle will work) and an iron (use with supervision or have your adult do this step). Cut the bottom off the paper bag and slit it open, so you have a flat piece of brown paper. Divide into thirds. Wad a piece up into a ball. Open it up and wad it up again. Repeat this over and over. Eventually, the paper will become soft and pliable. Open it up and draw birds and flowers or other objects in bright colors. Once your drawing is done, outline everything with the black marker. Use paraffin or a candle to coat your entire drawing with wax.