The History of the Gaelic Games in Ulster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2010 Annual Congress Papers

Cumann Camógaíochta na nGael Ardchomhairle, Páirc an Chrocaigh, Ascal San Seosaph, Áth Cliath 3 Tel 01 865 8651 Fax 01 855 6063 email [email protected] web www.camogie.ie Cumann Camógaíochta na nGael – An Chomhdháil Bhliantúil 2010 Cumann Camógaíochta na nGael An Chomhdháil Bhliantúil 2010 March 26th/27th 2010 Keadeen Hotel, Newbridge, Co. Kildare. An Clár Dé hAoine, 26 Martá 2010 4.30 – 6.00pm Ceardlanna Forbatha Development Workshops 6.30 – 7.30pm Clárú Registration 8.00pm Fáilte ó Uachtarán Chill Dara, Welcome from Kildare President, Máire Uí Chonchoille Marie Woods Tinreamh agus Buanorduithe Check attendance and adopt Standing Orders Áiritheoirí a cheapadh Appoint tellers 8.15pm Ceardlann Rialacha Rules Workshop 9.15pm Miontuairiscí Chomhdháil 2009 Minutes Congress 2009 Tuairiscí ó na Comhairlí Cúige Reports from Provincial Councils Tuairiscí ó Londain, Meiriceá Thuaidh, Reports from London, North America, an Eoraip agus an Astráil Europe and Australia Tuairiscí ó C.C.A.O. agus Reports from CCAO and Comhairle na nIar-bhunscoileanna Post Primary Colleges Tuairiscí ó na Fochoistí Subcommittee Reports 10.15pm Críoch End Dé Sathairn, 27 Márta 2010 9.00 - 9.30am Clárú Registration 9.30am Tinreamh Check attendance Áiritheoirí a cheapadh Appoint tellers 9.35am Cuntais Airgeadais Financial Accounts 10.00am Tuairisc an Ard Stiúrthóra Ard Stiúrthóir's report 10.30am Strategic Plan 2010 - 2015 Strategic Plan 2010 - 2015 11.30am Tuairisc ar Fhorbairt Development Report 12.00 noon Aitheasc an Uachtarán President's Address 12.30 – 1.45pm Lón Lunch 1.45pm Plé ar Rialacha Open discussion on feedback on proposed rules 3.15pm Rúin Motions 4.25pm Ionad na Comhdhála, 2011 Venue for Congress 2011 4.30pm Críoch End Buanordaithe (Standing Orders) 1. -

West Tipperary Senior Hurling Final Match Programme 2000 Na~1N Luthchleas Gael· Tiobraid Arann Thiar

West Tipperary Senior Hurling Final Match Programme 2000 na~1n Luthchleas Gael· Tiobraid Arann Thiar I . IN GOLDEN· 20th AUGUST, 2000 Best lVis/,es from . .. RICHARD GERRY HEFFERNAN B. Sc., (Pharm.), M.P.S.1. CROSSE Dispensing & Building Veterinary Chemist Contractor DUNDRUM Co. Tipperary DUNDRUM Phone: (062) 71394 F OR ALL YOU R B UILDING NEEDS Best wishes to both CONTACT NO. 062-71318 teams Wishing both teams every . ~,; ci · , - . t.. success from . .. -- •. .:L.' ., 1!I'\r~.~ - lRcctorp ~ousc P,P, O'Dwyer ~oteI GENERAL HARDWARE Member of Besl Western International MERCHANT DlIlIllrll III , Dundrum Co. Tipperary <CO. U::ippmlrp Tel. 062·71266. Fax: 062-71115 Telephone: 062 - 71427 Best Western Telex: 93348 Sunday Lunches @ £11 .95 See our new range of Weddings Bar lunches Mon . to Sat. £4.95 Lighting, Crafts & Giftware Best wishes to both teams on display 2 Fi\lLTe - Cm:haoiRleach l10bRaid ARann ThiaR As Chairman of the West Tipperary Board of the Gaelic Athletic Association it's a special honour and privilege for me to extend a cead mile failte to all Gaels to Golden sports'ield for the showpiece of our year, the 7151 Senior Hurling Final. Our divisional decider is always special, and this year it's extra special because it's the first of our New Millennium and it brings together two teams that have made such a huge contribution to the success of our games in this division and outside in both hurling and football. Knockavilla Kickhams, a club that achieved so ""'.L--' much in the old millennium with 16 senior hurling titles and two in the last three years, are a very experienced learn and with many players of inter-county experience are a formidable side. -

Nuachtlitir Samhain 2019

NOVEMBER 2019 NUACHTLITIR SAMHAIN 2019 FOR NEWS, VIDEOS AND FIXTURES www.gaa.ie Football Hurling Club General By Brendan Minnock, GAA Club Leadership Development Programme IS YOUR CLUB AGM READY? AA Clubs across the country The structure of the club committee are currently preparing for and elected at the AGM should adhere to rule holding their Annual General 7.2 of the Club Constitution. It includes Meeting. Considering the AGM is the officers specifically listed in this rule Gthe most important meeting of the year, and at least five other full members. In every effort should be made to ensure it this sample committee, there are seven • The executive committee shall decide • Nominations to serve on the executive is organised properly. positions other than the ones specifically upon a date, time and place for the committee shall be by any two full listed in rule: meeting (where possible, before the members whose membership fees are The Club AGM and how it is run is governed end of November) paid up to date in accordance with by the Club Constitution & Rules, which can 1. Chairperson • At least 28 days’ notice in writing must Rule 6.2 and who are not suspended or be found at the back of the GAA’s Official 2. Vice-Chairperson be given to full members. disqualified under the Club Constitution Guide (Appendix 5 of the 2019 edition). 3. Treasurer • Invite nominations for positions on the & Rules or the Official Guide. A productive AGM will present members 4. Secretary club executive for the following year • No business shall be transacted at any with an opportunity to review the work 5. -

Munster Championships Continue! V Tipp, 2Pm/4Pm @ P

Dates for your Nuachtlitir Coiste Chontae Chorcaí: Vol. 4 No. 12, June 19th 2012 Diary June 24th: Munster IHC/SHC S-Finals, Cork Munster Championships Continue! v Tipp, 2pm/4pm @ P. Well done to the Cork Senior Footballers, who defeated Kerry in the Uí Chaoimh Munster SFC Semi-Final on June 10th, earning themselves a place in the June 28th: Munster Munster Final against Clare on July 8th in Limerick. Development Grants Info night, 7.30pm @ P. Uí Chaoimh June 28th: Cork GAA Clubs’ Draw, Goleen July 3rd: County Board Meeting, 8.30pm July 8th: Munster SFC Final, Cork v Clare, 2pm @ Gaelic Grounds Some of the action from Cork v Kerry. Pics: Denis O’Flynn, for more, see www.gaacork.ie The Cork Senior Hurlers play Tipperary on Sunday next at 4pm in Páirc Uí Chaoimh in the Munster SHC Semi-final, preceded by the Intermediate clash between the two counties at 2pm. Best of luck to all Munster involved! Championship For all information on these games, including ticket prices, teams etc, see Tickets the Cork GAA website, www.gaacork.ie. Nothing beats being there! Tickets for Cork’s upcoming Munster Hurling Championship game in Páirc Uí Chaoimh can be purchased online at www.tickets.ie, or at selected Centra/SuperValu stores. Fantastic adult and juvenile group discounts are also available through clubs, where terrace tickets can be bought for as little as €10 per person! For all ticket information, see www.gaacork.ie. Cork’s Stephen McDonnell at Páirc Uí Rinn in advance of next Sunday’s clash with Tipperary. -

De Búrca Rare Books

De Búrca Rare Books A selection of fine, rare and important books and manuscripts Catalogue 141 Spring 2020 DE BÚRCA RARE BOOKS Cloonagashel, 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. 01 288 2159 01 288 6960 CATALOGUE 141 Spring 2020 PLEASE NOTE 1. Please order by item number: Pennant is the code word for this catalogue which means: “Please forward from Catalogue 141: item/s ...”. 2. Payment strictly on receipt of books. 3. You may return any item found unsatisfactory, within seven days. 4. All items are in good condition, octavo, and cloth bound, unless otherwise stated. 5. Prices are net and in Euro. Other currencies are accepted. 6. Postage, insurance and packaging are extra. 7. All enquiries/orders will be answered. 8. We are open to visitors, preferably by appointment. 9. Our hours of business are: Mon. to Fri. 9 a.m.-5.30 p.m., Sat. 10 a.m.- 1 p.m. 10. As we are Specialists in Fine Books, Manuscripts and Maps relating to Ireland, we are always interested in acquiring same, and pay the best prices. 11. We accept: Visa and Mastercard. There is an administration charge of 2.5% on all credit cards. 12. All books etc. remain our property until paid for. 13. Text and images copyright © De Burca Rare Books. 14. All correspondence to 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. Telephone (01) 288 2159. International + 353 1 288 2159 (01) 288 6960. International + 353 1 288 6960 Fax (01) 283 4080. International + 353 1 283 4080 e-mail [email protected] web site www.deburcararebooks.com COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: Our front and rear cover is illustrated from the magnificent item 331, Pennant's The British Zoology. -

A Seed Is Sown 1884-1900 (1) Before the GAA from the Earliest Times, The

A Seed is Sown 1884-1900 (1) Before the GAA From the earliest times, the people of Ireland, as of other countries throughout the known world, played ball games'. Games played with a ball and stick can be traced back to pre-Christian times in Greece, Egypt and other countries. In Irish legend, there is a reference to a hurling game as early as the second century B.C., while the Brehon laws of the preChristian era contained a number of provisions relating to hurling. In the Tales of the Red Branch, which cover the period around the time of the birth of Christ, one of the best-known stories is that of the young Setanta, who on his way from his home in Cooley in County Louth to the palace of his uncle, King Conor Mac Nessa, at Eamhain Macha in Armagh, practised with a bronze hurley and a silver ball. On arrival at the palace, he joined the one hundred and fifty boys of noble blood who were being trained there and outhurled them all single-handed. He got his name, Cuchulainn, when he killed the great hound of Culann, which guarded the palace, by driving his hurling ball through the hound's open mouth. From the time of Cuchulainn right up to the end of the eighteenth century hurling flourished throughout the country in spite of attempts made through the Statutes of Kilkenny (1367), the Statute of Galway (1527) and the Sunday Observance Act (1695) to suppress it. Particularly in Munster and some counties of Leinster, it remained strong in the first half of the nineteenth century. -

Gaa Master Fixtures Schedule

GAA MASTER FIXTURES SCHEDULE AN LÁR CHOISTE CHEANNAIS NA GCOMÓRTAISÍ 2017 Version: 21.11.2016 Table of Contents Competition Page Master Fixture Grid 2017 3 GAA Hurling All-Ireland Senior Championship 11 Christy Ring Cup 15 Nicky Rackard Cup 17 Lory Meagher Cup 19 GAA Hurling All-Ireland Intermediate Championship 20 Bord Gáis Energy GAA Hurling All-Ireland U21 Championships 21 (A, B & C) Hurling Electric Ireland GAA Hurling All-Ireland Minor Championships 23 Fixture Schedule Fixture GAA Hurling All-Ireland U17 Competition 23 AIB GAA Hurling All-Ireland Club Championships 24 GAA Hurling Interprovincial Championship 25 GAA Football All-Ireland Senior Championship 26 GAA Football All-Ireland Junior Championship 31 Eirgrid GAA Football All-Ireland U21 Championship 32 Fixture Fixture Electric Ireland GAA Football All-Ireland Minor Championship 33 GAA Football All-Ireland U17 Competition 33 Schedule AIB GAA Football All-Ireland Club Championships 34 Football GAA Football Interprovincial Championship 35 Allianz League 2017 (Football & Hurling) 36 Allianz League Regulations 2017 50 Extra Time 59 Half Time Intervals 59 GAA Master Fixture Schedule 2017 2 MASTER FIXTURE GRID 2017 Deireadh Fómhair 2016 Samhain 2016 Nollaig 2016 1/2 (Sat/Sun) 5/6 (Sat/Sun) 3/4 (Sat/Sun) AIB Junior Club Football Quarter-Final (Britain v Leinster) Week Week 40 Week 45 Week 49 8/9 (Sat/Sun) 12/13 (Sat/Sun) 10/11 (Sat/Sun) AIB Senior Club Football Quarter-Final (Britain v Ulster) 10 (Sat) Interprovincial Football Semi-Finals Connacht v Leinster Munster v Ulster Interprovincial -

2013 Annual Congress Papers

1 An Chomhdháil Bhliantúil 2013 Contents 1 Clár 2 Teachtaireacht ón Uachtarán 4 Highlights from 2012 6 Tuairisc an Ard Stiúrthóra Sealadach 27 Provincial and Overseas Reports 52 Sub-Committees Reports 67 Reports from Camogie Representatives on GAA Sub-Committees 71 Report and Financial Statements 82 Motions 90 Torthaí na gComórtas 2012 91 Principle Dates 2013 92 Soaring Stars 2012 93 All Stars 2012 An Chomhdháil Bhliantúil 2013 1 An Chomhdháil Bhliantúil 2013 22 agus 23 Márta 2013 Hotel Wesport, Mayo Dé hAoine, 22 Márta 4.30 - 5.30pm Integrated Fixtures Workshop and ‘Camogie For All’ Workshop 6.00 - 7.30pm Registration 8.00pm Fáilte 8.15pm Adoption of standing orders 8.20pm Minutes of Congress 2012 8.30pm Affiliations motion presentation – Q&A round table clarifications 9.00pm Reports: Provincial, International Units, National Education Councils, Sub-committees 10.00pm Críoch Dé Sathairn, 23 Márta 8.45am Registration 9.15am Financial Accounts 9.40am Ard Stiúrthóir’s Report 10.15am Address from John Treacy, CEO Irish Sports Council 10.50am Break 11.20am Consideration of motions 12.30am Address by Uachtarán Aileen Lawlor 1.00pm Lón 2.00pm Consideration of motions 3.50pm Venue for Congress 2014 4.00pm Críoch 7.30pm Mass 8.00pm Congress Dinner BUANORDAITHE (Standing Orders) An Cumann 1. The proposer of a resolution or an amendment may speak for five minutes. Camógaíochta 2. A delegate to a resolution or an amendment may not exceed three minutes. Ardchomhairle, 3. The proposer of a resolution or an amendment may speak a second time for three minutes before a vote is taken. -

PRESENTED in ASSOCIATION with Mcaleer & RUSHE and O'neills

LOOKING FORWARD TO THIS YEAR’S NATIONAL LEAGUES PRESENTED IN ASSOCIATION WITH McALEER & RUSHE AND O’NEILLS he GAA is central to Tyrone and the people 3 in it. It makes clear statements about Who Working as a Team we are and Where we’re from, both as Tindividuals and as a community. The Red CLG Thír Eoghain … Hand Fan is now a fixed part of the lead-in to the working to develop TYRONE GAA & OUR SPONSORS new Season for our young people. Read it. Enjoy it. and promote Gaelic But above all, come along to the Tyrone games and games and to foster be part of it all. ‘Walk into the feeling!’ local identity and After another McKenna Cup campaign culture across Tyrone that we can take many positives from, we’re approaching the Allianz League in It’s a very simple but very significant a very positive mind-set. We’ve always fact that the future of Tyrone as a prided ourselves on the importance County and the future of the GAA we place on every game and this year’s in our County, currently sit with Allianz League is no exception. the 20,000 pupils who attend our schools. These vitally important young Tyrone people are the main focus of the work we all do at Club, School and County level. Tyrone GAA is about providing a wholesome focus for our young people, about building their sense of ‘Who they are’ and ‘Where they are from’ and about bolstering their self-esteem and personal contentment. We’re producing this Fanzine for all those pupils … and also, of course, for their parents, guardians, other family members and, very importantly, their teachers. -

Why Donegal Slept: the Development of Gaelic Games in Donegal, 1884-1934

WHY DONEGAL SLEPT: THE DEVELOPMENT OF GAELIC GAMES IN DONEGAL, 1884-1934 CONOR CURRAN B.ED., M.A. THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PH.D. THE INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR SPORTS HISTORY AND CULTURE AND THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORICAL AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES DE MONTFORT UNIVERSITY LEICESTER SUPERVISORS OF RESEARCH: FIRST SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR MATTHEW TAYLOR SECOND SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR MIKE CRONIN THIRD SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR RICHARD HOLT APRIL 2012 i Table of Contents Acknowledgements iii Abbreviations v Abstract vi Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Donegal and society, 1884-1934 27 Chapter 2 Sport in Donegal in the nineteenth century 58 Chapter 3 The failure of the GAA in Donegal, 1884-1905 104 Chapter 4 The development of the GAA in Donegal, 1905-1934 137 Chapter 5 The conflict between the GAA and association football in Donegal, 1905-1934 195 Chapter 6 The social background of the GAA 269 Conclusion 334 Appendices 352 Bibliography 371 ii Acknowledgements As a rather nervous schoolboy goalkeeper at the Ian Rush International soccer tournament in Wales in 1991, I was particularly aware of the fact that I came from a strong Gaelic football area and that there was only one other player from the south/south-west of the county in the Donegal under fourteen and under sixteen squads. In writing this thesis, I hope that I have, in some way, managed to explain the reasons for this cultural diversity. This thesis would not have been written without the assistance of my two supervisors, Professor Mike Cronin and Professor Matthew Taylor. Professor Cronin’s assistance and knowledge has transformed the way I think about history, society and sport while Professor Taylor’s expertise has also made me look at the writing of sports history and the development of society in a different way. -

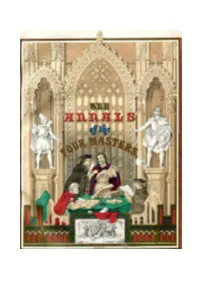

The Annals of the Four Masters De Búrca Rare Books Download

De Búrca Rare Books A selection of fine, rare and important books and manuscripts Catalogue 142 Summer 2020 DE BÚRCA RARE BOOKS Cloonagashel, 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. 01 288 2159 01 288 6960 CATALOGUE 142 Summer 2020 PLEASE NOTE 1. Please order by item number: Four Masters is the code word for this catalogue which means: “Please forward from Catalogue 142: item/s ...”. 2. Payment strictly on receipt of books. 3. You may return any item found unsatisfactory, within seven days. 4. All items are in good condition, octavo, and cloth bound, unless otherwise stated. 5. Prices are net and in Euro. Other currencies are accepted. 6. Postage, insurance and packaging are extra. 7. All enquiries/orders will be answered. 8. We are open to visitors, preferably by appointment. 9. Our hours of business are: Mon. to Fri. 9 a.m.-5.30 p.m., Sat. 10 a.m.- 1 p.m. 10. As we are Specialists in Fine Books, Manuscripts and Maps relating to Ireland, we are always interested in acquiring same, and pay the best prices. 11. We accept: Visa and Mastercard. There is an administration charge of 2.5% on all credit cards. 12. All books etc. remain our property until paid for. 13. Text and images copyright © De Burca Rare Books. 14. All correspondence to 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. Telephone (01) 288 2159. International + 353 1 288 2159 (01) 288 6960. International + 353 1 288 6960 Fax (01) 283 4080. International + 353 1 283 4080 e-mail [email protected] web site www.deburcararebooks.com COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: Our cover illustration is taken from item 70, Owen Connellan’s translation of The Annals of the Four Masters. -

Craobh Peile Uladh2o2o Muineachán an Cabhánversus First Round Saturday 31St October St Tiernach’S Park

CRAOBH PEILE ULADH2O2O MUINEACHÁN AN CABHÁNVERSUS FIRST ROUND SATURDAY 31ST OCTOBER ST TIERNACH’S PARK. 1.15 PM DÚN NA NGALL TÍR VERSUSEOGHAIN QUARTER FINAL SUNDAY 1ST NOVEMBER PÁIRC MACCUMHAILL - 1.30PM DOIRE ARD VERSUSMHACHA QUARTER FINAL SUNDAY 1ST NOVEMBER CELTIC PARK - 4.00 PM RÚNAI: ULSTER.GAA.IE 8 The stands may be silent but we know our communities are standing tall behind us. Help us make your SuperFan voice heard by sharing a video of how you Support Where You’re From on: @supervalu_irl @SuperValuIreland using the #SuperValuSuperFans SUPPORT 371 CRAOBH PEILE ULADH2O2O Where You’re From THIS WEEKEND’S (ALL GAMESGA ARE SUBJECTMES TO WINNER ON THE DAY) @ STVERSUS TIERNACH’S PARK, CLONES SATURDAY 31ST OCTOBER WATCH LIVE ON Ulster GAA Football Senior Championship Round 1 (1:15pm) Réiteoir: Ciaran Branagan (An Dún) Réiteoir ar fuaireachas: Barry Cassidy (Doire) Maor Líne: Cormac Reilly (An Mhí) Oifigeach Taobhlíne: Padraig Hughes (Ard Mhacha) Maoir: Mickey Curran, Conor Curran, Marty Brady & Gavin Corrigan @ PÁIRCVERSUS MAC CUMHAILL, BALLYBOFEY SUNDAY 1ST NOVEMBER WATCH LIVE ON Ulster GAA Football Senior Championship Q Final (1:30pm) Réiteoir: Joe McQuillan (An Cabhán) Réiteoir ar fuaireachas: David Gough (An Mhí) Maor Líne: Barry Judge (Sligeach) Oifigeach Taobhlíne: John Gilmartin (Sligeach) Maoir: Ciaran Brady, Mickey Lee, Jimmy Galligan & TP Gray VERSUS@ CELTIC PARK, DERRY SUNDAY 1ST NOVEMBER WATCH LIVE ON Ulster GAA Football Senior Championship Q Final (4:00pm) Réiteoir: Sean Hurson (Tír Eoghain) Réiteoir ar fuaireachas: Martin McNally (Muineachán) Maor Líne: Sean Laverty (Aontroim) Oifigeach Taobhlíne: Niall McKenna (Muineachán) Maoir: Cathal Forbes, Martin Coney, Mel Taggart & Martin Conway 832 CRAOBH PEILE ULADH2O2O 57 CRAOBH PEILE ULADH2O2O 11422 - UIC Ulster GAA ad.indd 1 10/01/2020 13:53 PRESIDENT’S FOREWORD Fearadh na fáilte romhaibh chuig Craobhchomórtas games.