Mimi Fox Published in Jazzimprov Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Isum 許諾楽曲一覧 更新日:2019/1/23

ページ:1/37 ISUM 許諾楽曲一覧 更新日:2019/1/23 ISUM番号 著作権者 楽曲名 アーティスト名 ISUM番号 著作権者 楽曲名 アーティスト名 ISUM番号 著作権者 楽曲名 アーティスト名 ISUM-1880-0537 JASRAC あの紙ヒコーキ くもり空わって ISUM-8212-1029 JASRAC SUNSHINE ISUM-9896-0141 JASRAC IT'S GONNA BE ALRIGHT ISUM-3412-4114 JASRAC あの青をこえて ISUM-5696-2991 JASRAC Thank you ISUM-9456-6173 JASRAC LIFE ISUM-4940-5285 JASRAC すべてへ ISUM-8028-4608 JASRAC Tomorrow ISUM-6164-2103 JASRAC Little Hero ISUM-5596-2990 JASRAC たいせつなひと ISUM-3400-5002 NexTone V.O.L ISUM-8964-6568 JASRAC Music Is My Life ISUM-6812-2103 JASRAC まばたき ISUM-0056-6569 JASRAC Wake up! ISUM-3920-1425 JASRAC MY FRIEND 19 ISUM-8636-1423 JASRAC 果てのない道 ISUM-5968-0141 NexTone WAY OF GLORY ISUM-4568-5680 JASRAC ONE ISUM-8740-6174 JASRAC 階段 ISUM-6384-4115 NexTone WISHES ISUM-5012-2991 JASRAC One Love ISUM-8528-1423 JASRAC 水・陸・そら、無限大 ISUM-1124-1029 JASRAC Yell ISUM-7840-5002 JASRAC So Special -Version AI- ISUM-3060-2596 JASRAC 足跡 ISUM-4160-4608 JASRAC アシタノヒカリ ISUM-0692-2103 JASRAC sogood ISUM-7428-2595 JASRAC 背景ロマン ISUM-5944-4115 NexTone ココア by MisaChia ISUM-1020-1708 JASRAC Story ISUM-0204-5287 JASRAC I LOVE YOU ISUM-7456-6568 NexTone さよならの前に ISUM-2432-5002 JASRAC Story(English Version) 369 AAA ISUM-0224-5287 JASRAC バラード ISUM-3344-2596 NexTone ハレルヤ ISUM-9864-0141 JASRAC VOICE ISUM-9232-0141 JASRAC My Fair Lady ft. May J. "E"qual ISUM-7328-6173 NexTone ハレルヤ -Bonus Tracks- ISUM-1256-5286 JASRAC WA Interlude feat.鼓童,Jinmenusagi AI ISUM-5580-2991 JASRAC サンダーロード ↑THE HIGH-LOWS↓ ISUM-7296-2102 JASRAC ぼくの憂鬱と不機嫌な彼女 ISUM-9404-0536 JASRAC Wonderful World feat.姫神 ISUM-1180-4608 JASRAC Nostalgia -

Misia Soul Jazz Session

Misia Soul Jazz Session Loading the chords for 'MISIA - MISIA SOUL JAZZ SESSION 楽曲試è´ãƒˆãƒ¬ãƒ¼ãƒ©ãƒ¼'. 18444 jam sessions ⢠chords: Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young - Teach Your Children. 9819 jam sessions ⢠chords: The Smashing Pumpkins - 1979. 11946 jam sessions ⢠chords: From our blog: Chord of the week â“ Pitch the G into a G# or flatten your A with an Ab, the chord remains the same. MISIA SOUL JAZZ SESSION / MISIA SUMMER SOUL JAZZ 2017 LIVE IN TOKYO SPOT Updated : 2017-11-28 08:20:23. MISIA - ゠スã—ã¦æŠ±ãã—ã‚㦠- MISIA SUMMER SOUL JAZZ 2017 Updated : 2017-12-30 06:32:16. MISIA - オルフェンズã®æ¶™ / MISIA SUMMER SOUL JAZZ 2017 LIVE IN TOKYO Updated : 2017-12-06 09:18:57. 月 - MISIA / 星空ã®ãƒ©ã‚¤ãƒ´ï¼“ Music Is A Joyforever Updated : 2017-09-11 14:11:33. ãMISIA SOUL JAZZ SESSIONã‘LIVE Blu-ray & DVD ç‰¹åˆ¥å…ˆè¡Œä¸Šæ˜ ä¼šé–‹å‚¬! Updated : 2017-10-31 09:07:36. 170714 MISIA SUMMER SOUL JAZZ Short Ver Updated : 2017-07-14 05:35:15. #MISIA #LIVE MISIA - MAWARE MAWARE / MISIA SUMMER SOUL JAZZ 2017 LIVE IN TOKYO Updated : 2018-05-31 07:35:15. Performed by - MISIA. Album - SOUL JAZZ SESSION. Release Date - 26 / 07 / 2017. Genre - J-Pop / R&B / Jazz / Soul. Bitrate - 320 Kbps. Origin - Japón ( Tokyo, Japan). Misia soul jazz session. 2016.03.09. MISIA 星空ã®ãƒ©ã‚¤ãƒ´ SONG BOOK HISTORY OF HOSHIZORA LIVE. -

Professor, CONDUCTOR, Traveler, Outdoorsman by Teresa Kelly Dr

IN-DEPTH 1 RICKEY BADUA professor, CONDUCTOR, Traveler, outdoorsman By Teresa Kelly Dr. Rickey Badua has joined the Cal Poly Pomona Music Department as a tenure track faculty member where he will offer leadership in the instrumental music area. He will be teaching Concert Band, Wind Ensemble, conducting, and other instrumental related classes. Dr. Badua received his Bachelor of Music in Music Education and his Master of Arts in Wind Conducting from the University of Puget Sound, and his Doctor of Musical Arts from the University of Georgia. Prior to that he taught at the Peninsula High School in Gig Harbor, WA as the Director of Bands, Arts Department Chair and District Music Coordinator. He is an avid trombonist and pianist. What first got you interested the trombone quickly and was you in music? immediately moved into the I grew up in Honolulu, HI and advanced band. By age 14, I began piano lessons at age 4 with began private trombone lessons my mother’s best friend, Estrellita with the principal trombonist Goulart. After one year of being of the Honoululu Symphony in her piano class, she asked me and trombone professor at the if I enjoyed music and would like University of Hawaii, Jim Decker to continue. I said YES! Music (currently teaching at Texas and playing piano was fun and it Tech University). came natural to me at that age. From that point on I was involved What is it about this instrument with a lot of music throughout my that makes you want to pass it education in school. -

Farewell to the Jazz Preacher

gram JAZZ PROMOTING AND NURTURING JAZZ IN CHICAGO OCTOBER 2020 WWW.JAZZINCHICAGO.ORG FAREWELL TO THE JAZZ PREACHER BY LLOYD SACHS Chicago's jazz community is so tight, the loss of any of its members is keenly felt. But such was the special largesse of Ira Sullivan – in musical, interpersonal and spiritual terms – news of his recent death had an especially strong impact on the artistic associates, students, fans and critics he left behind. Though Sullivan had lived for decades in Florida, where he lifted the jazz scene with his bandstand presence and inspired generations of students as an instructor at the University of Miami Frost School of Music, he never stopped being present in the hearts and souls of Chicago's finest. Few artists have worn the Windy City jazz tradition with greater meaning or class than Sullivan did with his matter of fact brilliance, personal approach to classic bebop and utter redefining of versatility. He was probably best known as a saxophonist – he played tenor, soprano, alto and baritone – but he was also a great trumpeter and stalwart on the flute. Whatever instrument he picked up he played with resounding personal depth. In paying tribute to Sullivan, musician after musician recounted the glories of hanging out with him as well as playing with him – of learning things from him that they had no idea they didn't know. For one of those players, the late saxophone hero Lin Halliday, that included learning how to get his horn psychically fixed. At the Green Mill one night, as a member of trumpeter Brad Goode's band, Halliday was Ira Sullivan (1931-2020) photo by Lauren Deutsch having trouble with the keys on his tenor. -

Isum 許諾楽曲一覧 更新日:2019/4/10

ページ:1/39 ISUM 許諾楽曲一覧 更新日:2019/4/10 ISUM番号 著作権者 楽曲名 アーティスト名 ISUM番号 著作権者 楽曲名 アーティスト名 ISUM番号 著作権者 楽曲名 アーティスト名 ISUM-1880-0537 JASRAC あの紙ヒコーキ くもり空わって ISUM-2952-2595 JASRAC OVER by Naoya Urata, Mitsuhiro Hidaka&Shuta Sueyoshi ISUM-6512-1708 JASRAC 五右衛門 ISUM-3412-4114 JASRAC あの青をこえて ISUM-0776-1029 NexTone Perfect ISUM-9188-0536 JASRAC 残響6/8センチメンタル ADAM at ISUM-4940-5285 JASRAC すべてへ ISUM-3256-6174 NexTone S.O.L ISUM-6124-2103 JASRAC 半丁猫屋敷 ISUM-5596-2990 JASRAC たいせつなひと ISUM-5152-5681 JASRAC SAILING ISUM-7140-1424 JASRAC 六三四 Afrojack VS. Thirty Seconds To ISUM-6812-2103 JASRAC まばたき ISUM-8068-5680 NexTone STORY ISUM-2176-6174 JASRAC Do Or Die (Remix) 19 Mars ISUM-8636-1423 JASRAC 果てのない道 ISUM-8212-1029 JASRAC SUNSHINE ISUM-2300-2990 JASRAC Diva AFTERSCHOOL ISUM-8740-6174 JASRAC 階段 ISUM-5696-2991 JASRAC Thank you ISUM-9020-6568 JASRAC 今すぐKiss Me Against The Current ISUM-8528-1423 JASRAC 水・陸・そら、無限大 ISUM-8028-4608 JASRAC Tomorrow ISUM-0764-5681 JASRAC Beautiful Life ISUM-3060-2596 JASRAC 足跡 ISUM-4936-0141 JASRAC Us ISUM-9904-6568 JASRAC Believe ISUM-7428-2595 JASRAC 背景ロマン ISUM-3400-5002 NexTone V.O.L ISUM-7604-1424 JASRAC E.O. ISUM-0204-5287 JASRAC I LOVE YOU ISUM-0056-6569 JASRAC Wake up! ISUM-3728-1029 JASRAC Family 369 ISUM-0224-5287 JASRAC バラード ISUM-5968-0141 NexTone WAY OF GLORY ISUM-8096-1029 JASRAC FEEL IT ISUM-9232-0141 JASRAC My Fair Lady ft. May J. "E"qual ISUM-6384-4115 NexTone WISHES ISUM-6844-2103 JASRAC From Zero ISUM-5776-3720 JASRAC Loving Proof @djtomoko n Ucca-Laugh ISUM-1124-1029 JASRAC Yell ISUM-8996-6568 JASRAC HANABI AAA ISUM-5580-2991 -

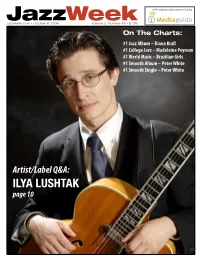

Is Top Smooth Jazz Single for 13Th Straight Week

JazzWeek with airplay data powered by jazzweek.com • October 9, 2006 Volume 2, Number 45 • $7.95 On The Charts: #1 Jazz Album – Diana Krall #1 College Jazz – Madeleine Peyroux #1 World Music – Brazilian Girls #1 Smooth Album – Peter White #1 Smooth Single – Peter White Artist/Label Q&A: ILYA LUSHTAK page 10 JazzWeek This Week EDITOR/PUBLISHER Ed Trefzger MUSIC EDITOR Tad Hendrickson rank Zappa famously once wrote, “Jazz isn’t dead; it just CONTRIBUTING WRITER/ smells funny.” If Frank were around today, I wonder what PHOTOGRAPHER Fhe’d say about smooth jazz. Tom Mallison On Monday, Oct. 2, the format lost its third station in as many PHOTOGRAPHY months as Dallas’ KOAI switched to the new format du jour, Barry Solof “rhythmic AC.” Outside of its original strongholds, smooth jazz Contributing Editors radio and record sales seem to be heading into oblivion. Keith Zimmerman It’s always been easy for mainstream jazz fans and artists to Kent Zimmerman sneer at smooth jazz artistically – but for many years it has been a Founding Publisher: Tony Gasparre solid performer, having been sold as part of a whole lifestyle. But ADVERTISING: Devon Murphy that whole yuppie/white wine scene seems to has faded, and the Call (866) 453-6401 ext. 3 or format is fading, too. email: [email protected] Even so, Broadcast Architecture, long the 800-lb. gorilla of SUBSCRIPTIONS: the format, is launching a smooth jazz network, including Chica- Free to qualified applicants go morning stalwart Ramsey Lewis. You’ve got to wonder where Premium subscription: $149.00 per year, that will find outlets – the economics don’t seem to be there yet w/ Industry Access: $249.00 per year To subscribe using Visa/MC/Discover/ for it to be profitable as a secondary HD channel for the few hun- AMEX/PayPal go to: dreds with receivers. -

Tuning In: Key Players in the Music Scene at Brown By: Emilia Ruzicka and Ivy Scott

Tuning In: Key Players in the Music Scene at Brown By: Emilia Ruzicka and Ivy Scott [Title credits roll over footage of empty recording studio. “Canada Goose” by Kyle McCarthy (feat. Temma) plays. Faintly, two doors slam simultaneously. Ivy and Emilia both enter the frame from opposite sides, spinning charmingly on rolling swivel chairs. Chairs stop magically when both are center frame, co-hosts are smiling and slightly disoriented from the spinning, but otherwise perfectly coiffed.] Emilia: Hello everybody and welcome back to a new episode of Tuning In: Key Players in the Rhode Island Music Scene. I’m your co-host Emilia Ruzicka-- Ivy: And I’m Ivy Scott. Today we’ll be venturing up a certain College Hill to bring you another special University Edition of Tuning In. So why don’t you guys join us as we take a closer look at some of the ‘key players’ (both laugh) in the music scene at Brown. [applause track plays] [Cut to ground floor lobby of Brown’s Smith-Buonanno Hall, applause track replaced with real applause. Room is packed with students dancing and laughing. Cut to shot from side camera which is close-up on several members of Falling Walrus. Pan from drummer to trumpet to lead singer, all illuminated by the multicolored string lights that line the walls, before focusing on one particularly enthusiastic group of fans who are singing along cheerfully and waving their hands. Zoom in on one student waving a large cardboard cutout, it appears to be of the drummer. Cut back to main camera, which fades as band finishes their last song. -

Isum 許諾楽曲一覧 更新日: 2018/3/20

ページ:1/31 ISUM 許諾楽曲一覧 更新日: 2018/3/20 ISUM番号 著作権者 楽曲名 アーティスト名 ISUM番号 著作権者 楽曲名 アーティスト名 ISUM番号 著作権者 楽曲名 アーティスト名 ISUM-1880-0537 JASRAC あの紙ヒコーキ くもり空わって ISUM-0620-5286 JASRAC 出逢いのチカラ ISUM-1876-5286 NexTone キズナ ISUM-3412-4114 JASRAC あの青をこえて ISUM-3760-2102 NexTone 唇からロマンチカ ISUM-4244-1029 NexTone セプテンバーさん ISUM-4940-5285 JASRAC すべてへ ISUM-0612-4114 JASRAC 虹 ISUM-4584-1707 JASRAC ポラリス AAA ISUM-5596-2990 JASRAC たいせつなひと ISUM-0604-5287 NexTone 風に薫る夏の記憶 ISUM-4136-4608 JASRAC 茜さす ISUM-6812-2103 JASRAC まばたき ISUM-7432-2102 JASRAC 涙のない世界 ISUM-6552-4115 JASRAC 歌鳥風月 Aimer 19 ISUM-8636-1423 JASRAC 果てのない道 ISUM-3700-1030 JASRAC 恋音と雨空 ISUM-9296-6568 JASRAC 糸 ISUM-8740-6174 JASRAC 階段 ISUM-1940-4608 JASRAC Climax Jump AAA DEN-O form ISUM-7772-2102 JASRAC 小さな星のメロディー ISUM-8528-1423 JASRAC 水・陸・そら、無限大 ISUM-3328-3719 JASRAC From Dusk Till Dawn abingdon boys school ISUM-0200-1708 JASRAC 蝶々結び ISUM-3060-2596 JASRAC 足跡 ISUM-9804-0141 JASRAC トドイテマスカ? ISUM-6224-4115 JASRAC 六等星の夜 absorb ISUM-7428-2595 JASRAC 背景ロマン ISUM-7244-1708 JASRAC 愛ノ詩 ISUM-0856-5681 JASRAC #好きなんだ ISUM-0204-5287 JASRAC I LOVE YOU ISUM-3520-6569 NexTone JUST LIKE HEAVEN ISUM-6392-0536 JASRAC 365日の紙飛行機 369 ISUM-0224-5287 JASRAC バラード ISUM-5340-0141 NexTone NOW HERE ISUM-3228-1425 JASRAC Beginner ACE OF SPADES ISUM-9232-0141 JASRAC My Fair Lady ft. May J. "E"qual ISUM-4620-1707 NexTone WILD TRIBE ISUM-7964-6173 JASRAC Everyday、カチューシャ ISUM-5580-2991 JASRAC サンダーロード ↑THE HIGH-LOWS↓ ISUM-5288-5286 NexTone 誓い ISUM-1584-4608 JASRAC Green Flash ACE OF SPADES×PKCZ® ISUM-1180-4608 JASRAC Nostalgia ISUM-2192-2990 JASRAC TIME FLIES ISUM-1652-4608 JASRAC LOVE TRIP feat. -

Joshua Redman Quartet at Annenberg Everything You Wanted to Know About Sax Judy Weightman November 12, 2013 in Music & Opera Share: � ✉

Joshua Redman Quartet at Annenberg Everything you wanted to know about sax Judy Weightman November 12, 2013 in Music & Opera Share: ✉ The saxophone was invented in 1840 by Adolphe Sax, a Belgian who yearned to create an instrument that would blend the power of brass with the adaptability of woodwinds. It was originally created for use in military bands and adopted with gusto by Philadelphia’s Mummers, but it never entirely caught on in Classical music, though some modern composers (Prokofiev, Shostakovich, Vaughn Williams) have availed themselves of its distinctive timbre. Instead, this most modern instrument found its home as the quintessential instrument in the most modern musical genre: jazz. After providing part of the sonic mix in the big band era of the 1930s, saxophonists of the ‘40s led the rebellion against the strictures of swing. From Charlie Parker to John Coltrane to Ornette Coleman to Stan Getz, sax players have been the groundbreakers and genre- shifters. Joshua Redman was hailed as the next great savior of jazz when he burst on the scene in 1991, the year he graduated from Harvard and also won the Thelonious Monk International Jazz Saxophone Competition. In the 22 years since, he’s performed regularly, both with his own bands and as a sideman for others, including his saxophonist father Dewey Redman. Not quite in Daddy's footsteps. Orchestras, too Although Joshua has mostly remained loyal to his first love— bebop— he’s also dabbled with fusion (in a trio called the Elastic Band), and his most recent album, Walking Shadows, featured ballads played by a quartet backed by a full string orchestra. -

Poncho Sanchez Standard-Bearer

June 2013 | No. 134 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com PONCHO SANCHEZ STANDARD-BEARER BOB • NATE • KAMAU • IMPROVISING • EVENT DOROUGH WOOLEY ADILIFU BEINGS CALENDAR SMOKE JAZZ & SUPER CLUB PRESENTS “DREAMING IN BLUE” MILES DAVIS FEStival 2013 May 24 -June 30 Friday & Saturday May 24 & 25 Wednesday June 5 Wednesday June 19 “Kind Of Blue” MILES TONES DUANE EUBANKS QNT FT JIMMY COBB SEXTET GIACOMO GATES MULGREW MILLER Javon Jackson (ts) • Justin Robinson (as) Abraham Burton (ts) • Ameen Saleem (b) Eddie Henderson (tp) • Mike LeDonne (p) CD Release Event Eric McPherson (dr) Buster Williams (b) Friday & Saturday June 7 & 8 Friday & Saturday June 21 & 22 Wednesday May 29 JOE FARNSWORTH QUARTET “MILES BEYOND” “MILESTONES” FT DAVID KIKOSKI LARRY WILLIS QNT FREDDIE HENDRIX QNT FEATURING Abraham Burton (ts) • Orrin Evans (p) • Josh Evans (tr) • Dwayne Burno (b) BUSTER WILLIAMS Corcoran Holt (b) • Eric McPherson (dr) Friday & Saturday May 31 & June 1 & AL FOSTER Wednesday June 26 “SOMEDAY MY PRINCE WILL Jeremy Pelt (tr) • Javon Jackson (ts) JOSH EVANS SEXTET COme” Vincent Herring (as) • Abraham Burton (ts) EDDIE HENDERSON QNT Wednesday June 12 Orrin Evans (p) • Dezron Douglas (b) • Chris Beck (dr) Wayne Escoffery (ts) • Dave Kikoski (p) Doug Weiss (b) • Carl Allen (dr) THE MICHAEL DEASE QUINTET Friday & Saturday June 28 & 29 Etienne Charles (tr) • Glenn Zaleski (p) • Linda Oh (b) Colin Stranahan (dr) “BitCHES BREw “ Sunday June 2 LENNY WHITE QUINTET THE DEE DANIELS QNT Friday & Saturday June 14 & 15 FEATURING JEREMY PELT THE -

Phil Minton & Maggie Nicols Interviewed by Chris Tonelli

Critical Studies in Improvisation / Études critiques en improvisation, Vol 10, No 2 Social Virtuosity and the Improvising Voice Phil Minton & Maggie Nicols Interviewed by Chris Tonelli Introduction In 1977, an extraordinary album with the simple title Voice was released on Ogun Records. What made the record extraordinary was its focus on the free improvisation of only the title instrument. In his commentary on the record jacket, Ogun co-founder Keith Beal wrote that "It is not often that one sees a vocalist doing a jazz gig these days. When there are four of them it is very rare indeed and when these four vocalists are singing unaccompanied it must be unique." It was. Unfortunately, voice-only free jazz group performances are still relatively rare: although the precedent set by the vocalists on this album and other improvising vocalists has presented free jazz/improvisatory vocal practice as a creative option, and although the contemporary global free jazz/improvised music community currently includes hundreds of active improvising vocalists, old prejudices that see the voice as too emotional, insufficiently abstract, or lacking in rigour still linger and prevent the voice from becoming an equal player in the field of improvised music. The following interview with Maggie Nicols and Phil Minton, two of the four vocalists who made up Voice, is a conversation with two of free jazz's most significant vocalists, a significance derived not only from their longevity1 and the innovations they are responsible for,2 but also from the ethics governing how their practices developed. Minton's championing of unconventional vocal sounds is an ethical necessity for him. -

The Life, Composing and Impact of Kenny Wheeler

Portland State University PDXScholar University Honors Theses University Honors College 5-24-2019 The Life, Composing and Impact of Kenny Wheeler Quinn Walker Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/honorstheses Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Walker, Quinn, "The Life, Composing and Impact of Kenny Wheeler" (2019). University Honors Theses. Paper 676. https://doi.org/10.15760/honors.690 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. The Life, Composing and Impact of Kenny Wheeler by Quinn Walker An undergraduate honors thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Music In University Honors And Jazz Studies, Emphasis in Trumpet Performance Thesis Advisor George Colligan Portland State University 2019 Walker 1 ABSTRACT Since its birth in the beginning of the twentieth century, jazz music has had an immense impact on the world. As jazz began to grow, many sub-genres developed within jazz, incorporating elements of blues, funk, rock, free music, and complex harmony. As a jazz musician myself, something always fascinates me is the diversity within the genre. With the development of steaming platforms such as Spotify, it has never been easier to discover the immense amount of jazz that musicians have gifted to this world. The popularity of jazz music has been in steady decline since the 1960s.