Interview with Ms. Helen Weinland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Population Advisor Project Ministry of Public Health N

POPULATION ADVISOR PROJECT MINISTRY OF PUBLIC HEALTH N'DJAMENA, CHAD FINAL REPORT Submitted to the Agency for International Development N'Djamena, Chad to the Agency for International Development Washington, D.C. and to REDSO/WCA By Leslie Leila Brandon M.S.W., M.P.H. Population Advisor May 26, 1989 HARVARD INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT FINAL REPORT Submitted to the Agency for International Development N'Djamena, Chad to the Agency for International Development Washington, D.C. and to REDSO/WCA By Leslie Leila Brandon M.S.W., M.P.H. Population Advisor May 26, 1989 HARVARD INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A successful project is never the effort of just one person it takes a cohesive and committed team to make it work. I was very fortunate not only to be a part of several different teams but to have the support of many people who really cared about the success of the first family planning project in Chad. I owe each of them my deepest appreciation and thank them for their generosity and persistent commitment to Chad and to family planning. The follow:ng institutions and individuals are: 1. The Agency for International Development/N'Djamena a) Mrs. Diane Blane: My supervisor at USAID and the one person who should take the credit for making the project work. Without her loyalty, commitment and encouragement the project would have encountered endless obstacles. b) Mr. Bernie Wilder: The USAID representative whose commitment to family planning issues helped make the project successful. c) Mr. John Woods: Deep appreciation for all his support and wisdom in the beginning of the project as the USAID representative. -

The Foreign Service Journal, February 1993

PROBLEMS AND PRECEDENTS SOMALIA AS VICTIM: EACT AND FICTION Tv tuai/UiiLiiiru SEEKING A SOLUTION VIGNETTE PROM OLD MOGADISHU Li\I • V UlLliliUVt VI I I • I -I • 1 Li.I I LKLllTI I I I I I M l-LUS: IxLHUUl- LILTULI lill liRtlltiyilci tlLLLL Liu.' LLULULALLIUVCIL UliLLLLLLcUllUS When it’s time to entrust your valuable belongings for moving or storage, you can select Interstate with confidence. Since 1943 Interstate has represented a Now that your choice is made, call Interstate and tradition of excellence and quality for all your ask for our State Department Coordinators at (703) moving needs. For the sixth consecutive year, 569-2121, extension 233, or if you are out of town, Interstate has been selected as a primary (800) 336-4533, extension 233. contractor to provide moving and storage services for United States Department of State Our competition is good, but let us show personnel. Do you want a moving company you that Interstate is the best!! with trained professional movers, climate- It’s your choice! controlled storage, personal consultation throughout your move, a proven record of performance? Then choose Interstate. We invite you to ask your colleagues, review our ™INTERSTATE commendation letters from prior moves, and EXCELLENCE IN MOVING A STORAGE visit our facilities. 5801 Rolling Road, Springfield, VA 22152-1041 MC 1745 FMC 2924 When You Go Abroad, We Go Abroad. ★ ★ Clements & Company The Leaders in Insurance for the Foreign Service. At Clements & Company, Our Primary Products Include: we are the leaders in providing • Automobile domestic and international • Household Effects coverage for the foreign • Personal Liability service community. -

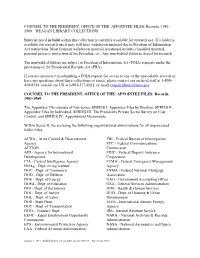

APPOINTEE FILES: Records, 1981- 1989 – REAGAN LIBRARY COLLECTIONS

COUNSEL TO THE PRESIDENT, OFFICE OF THE: APPOINTEE FILES: Records, 1981- 1989 – REAGAN LIBRARY COLLECTIONS Material noted in bold within this collection is currently available for research use. If a folder is available for research use it may still have withdrawn material due to Freedom of Information Act restrictions. Most frequent withdrawn material is national security classified material, personal privacy, protection of the President, etc. Any non-bolded folder is closed for research. The non-bolded folders are subject to Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests under the provisions of the Presidential Records Act (PRA). If you are interested in submitting a FOIA request for access to any of the unavailable records or have any questions about these collections or series, please contact our archival staff at 1-800- 410-8354, outside the US at 1-805-577-4012, or email [email protected] COUNSEL TO THE PRESIDENT, OFFICE OF THE: APPOINTEE FILES: Records, 1981-1989 The Appointee File consists of four series: SERIES I: Appointee Files by Position; SERIES II: Appointee Files by Individual; SERIES III: The President's Private Sector Survey on Cost Control, and SERIES IV: Appointment Memoranda Within Series II, we are using the following organizational abbreviations for all unprocessed folder titles: ACDA - Arms Control & Disarmament FBI - Federal Bureau of Investigation Agency FCC - Federal Communications ACTION Commission AID - Agency for International FDIC - Federal Deposit Insurance Development Corporation CIA - Central Intelligence Agency FEMA - Federal Emergency Management DOAg - Dept. of Agriculture Agency DOC - Dept. of Commerce FNMA - Federal National Mortgage DOD - Dept. of Defense Association DOE - Dept. -

Best Available Copy

POPULA TION TECHNIC4 ASSfSTMCE PROJECT OCCASIONL PRI1EH John Blane Matthew Ffiednan Occasional Paper NO. 5 Published November 2i, 1990 G~QSSLy Executive Sumrrxary Chapter 2 Compliance with the Mexico City Policy 9 Chapter 3 Grantee and Subgrantee Understandkg of the Requirements of 8eMexico City Policy 21 Chapter 5 Concluding Remarks 29 Table i TLegal Status of Abortion in the Six Countries in the Mexico City Yofiq Study 4 Table 2 Number of Subproject and Clinic Visits, by Countrqi and Cooperating Agency 6 Table 3 Categories of Clinic Staff Interviewed in Depth, by Country 7 Table 3 Overview of Activities Related to Compliance with the Mexica City Policy 9 Table 5 Percent of Subprojects Informing Staff on the Mexicc Ciry Policy, by Method of Communication 14 Appendix A A-I.D. Mexico City Policy Procedures Appendix I3 Summary of Research Findings on Abortion in the Six Countries under Rcview ~&endixC Scope of Work: Mexico City Policy Impternentation Study Appendix D frofile of Five Cooperating Agencies Appendix E Mexico City Policy Implementation Study Checklist Appendix F Organizarioils Visited ... - 111 - Glossary A.T.D. U.S. Agency for International Development AIDS Acquired immune deficiency syxdrome AVSC Association for Vofuntary Surgical Contraception CA Cooperating Agency CEDf A Centre tbr Develcpment and Population Activities m1 Family Health International FTA Family Planning Association FPfA Family Pla~lningInternatianaI Assistance IEC Information, education, and communication IPPFMR International Planned Parenthood Federation,KVestem Hemisphere Region IUD Intrauterine device NGO Nan-governmental organization NORPLAVP Five-pear contraceptive implant POPLLYE On-line computer population resource PQPTECH Population Technical Assistance Project PVO Private voluntary organization TFPA Turkey Family Pf anning Association usm U.S. -

Table of Contents

GABON COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS L. Michael Rives 1961-1963 Director for Central African Countries- State Department, Washington, DC Dorothy E. Eardley 1963-1965 Secretary to the Ambassador, Libreville Robert V. Keeley 1963-1965 Congo-Leopoldville Desk Officer- Central African Affairs, Washington, DC Thompson R. Buchanan 1966-1967 Deputy Chief of Mission, Libreville John Propst Blane 1966-1969 Desk Officer, State Department, Washington, DC Harvey F. Nelson, Jr. 1967-1969 Deputy Chief of Mission, Libreville Richard Funkhouser 1969-1970 Ambassador, Gabon Edward Gibson Lanpher 1969-1971 Political Officer, Libreville Nancy Forbord 1969-1972 Representative to African-American Institute, Libreville Fernando E. Rondon 1970 Madagascar Desk Officer- State Department, Washington, DC Laurent E. Morin 1970 Alternate Country Director- African Bureau, Washington, DC James K. Bishop Jr. 1970-1972 Desk Officer- Central African Affairs, Washington, DC John R. Countryman 1971-1975 Deputy Chief of Mission, Libreville John A. McKesson, III 1971-1975 Ambassador, Gabon Michael P.E. Hoyt 1972-1974 Rhodesian Desk Officer-State Department, Washington, DC 1 Andrew Steigman 1975-1977 Ambassador, Gabon Arthur T. Tienken 1978-1981 Ambassador, Gabon Francis Terry McNamara 1981-1984 Ambassador, Gabon Herman J. Rossi III 1982-1984 Deputy Chief of Mission, Libreville Larry C. Williamson 1984-1987 Ambassador, Gabon Ronald K. McMullen 1988-1990 Economic-Commercial Officer, Libreville Keith L. Wauchope 1989-1992 Ambassador, Gabon Joseph C. Wilson, IV 1992-1995 Ambassador, Gabon L. MICHAEL RIVES Director for Central African Countries- State Department Washington, DC (1961-1963) L. Michael Rives was born in New York in 1921. He received a bachelor's degree from Princeton University in 1947 and joined the Foreign Service in 1950. -

Key Officers Foreign Service Posts

to/S artment of State Key Officers Foreign Service Posts Guide for Business Representatives It is most Important that correspondence to a Foreign Service post be addressed to a section or position rather than to an officer by name. This will eliminate delays resulting from the for warding of official mail to officers who have transferred. Normally, correspondence con cerning commercial matters should be ad dressed simply "Commercial Section" followed by the name and correct mailing address of the post. (Samples of correct mailing addresses ap pear on page x.) DEPARTMENT OF STATE Publication 7877 Revised January 1984 FOREIGN AFFAIRS INFORMATION MANAGEMENT CENTER Publishing Services Division For Key Officer updates: Call (202) 632-1068 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402. KEY OFFICERS OF FOREIGN SERVICE POSTS I Guide for Business Representatives The Key Officers Guide lists key officers at For eign Service posts with whonn American business representatives would most likely have contact. All embassies, missions, consulates general, and con sulates are listed. At the head of each U.S. diplomatic mission are the Chief of Mission (with the title of Ambassador, Minister or Charge d'Affaires) and the Deputy Chief of Mission. These officers are responsible for all com ponents of the U.S. Mission within a country, includ ing consular posts. At larger posts, Commercial Officers represent U.S. commercial interests within their country of I assignment. Specializing in U.S. export promotion, Commercial Officers assist American business through: arranging appointments with local busi ness and government officials; providing counsel on local trade regulations, laws, and customs; iden tifying importers, buyers, agents, distributors, and joint venture partners for U.S. -

Africa Notes (July 1, 1982), I Wrote: "With the Publication of CSIS Africa Notes, a New Dimension Is Added to the Center's African Studies Program

Number 82 February 29, 1988 A publication of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, Washington, D.C. Whos Who, and Where: A Guide to Key Personnel in U.S.-African Diplomacy In the first issue of CSIS Africa Notes (July 1, 1982), I wrote: "With the publication of CSIS Africa Notes, a new dimension is added to the Center's African Studies Program. Not all articles we publish . will be as irreverent as this issue's tour of five countries of East Africa [Jerry Funk's "Observations on Strategic Realities and Ideological Red Herrings on the Horn of Africa"], but all will be concerned in one way or another with destereotyping. The problem with boxing and labeling African leaders and states as 'good guys' and 'bad guys' is that boxes and labels devised in either Moscow or Washington tend to disintegrate in the African sun. Thus, we will be looking through a variety of prisms at African political configurations, personalities, conflicts, economic pressures, external relationships , ... and policy options for the United States." In the five and a half years since the 1982 launching, we have produced 82 issues on a wide range of policy-relevant topics (see list on page 7) written by more than 40 authors. Our subscribers in the United States and in over 30 other countries fall generally into the categories whose special needs we sought to serve from the outset- "decision makers, analysts, and trailblazers with Africa-related responsibilities in governments, corporations, the media; research institutions, universities, and other arenas." One of the most popular issues published from time to time has been our "Who's Who, and Where" guide to key personalities in U.S.-African diplomatic relations. -

Africa Notes, Suite 400, 1800 K Street, NW., Washington, D.C

A publication of ihe African Studies Program of The Georgetown University Center for Strategic and International Studies No. 64 • November 22, 1986 Who's Who, and Where A Guide to Key Personnel in U.S.-African Diplomatic Relations U.S. Embassies in Africa Algeria (Algiers) Gambia (Banjul) Nigeria (Lagos) Ambassador: L. Craig Johnstone Ambassador: Herbert E. Horowitz Ambassador: Princeton Lyman Angola (Luanda) Ghana (Accra) Rwanda (Kigali) Diplomatic relations not yet established Ambassador: Steven R. Lyne Ambassador: John Edwin Upston Benin (Cotonou) Guinea (Conakry) Sao Tome & Principe (Sao Tome) Ambassador: Walter E. Stadtler Charge d'Affaires: William Mithoefer Relations managed from U.S. Embassy, Gabon Botswana (Gaborone) Guinea-Bissau (Bissau) Ambassador: Natale H. Bellocchi Ambassador: John Blacken Senegal (Dakar) Ambassador: Lannon Walker Burkina Faso (Ouagadougou) Cote d'lvoire (Abidjan) Ambassador: Leonardo Neher Ambassador: Dennis Kux Seychelles (Victoria) Ambassador: Irvin Hicks Burundi (Bujumbura) Kenya (Nairobi) Ambassador: James D. Phillips Ambassador: Elinor Greer Constable Sierra Leone (Freetown) Ambassador: Cynthia Shepard Perry Cameroon (Yaounde) Lesotho (Maseru) Ambassador: Myles R. R. Frechette Ambassador: Dr. S. L. Abbott Somalia (Mogadiscio) Ambassador: Frank Crigler Cape Verde (Praia) Liberia (Monrovia) Ambassador: Vernon Dubois Charge d'Affaires: Keith Wauchoup South Africa (Pretoria) Prenner, Jr. Ambassador: Edward J. Perkins Libya (Tripoli) Central African Republic (Bangui) U.S. interests represented by the Sudan (Khartoum) Ambassador: David C. Fields Embassy of Belgium Ambassador: G. Norman Anderson Chad (N'Djamena) Madagascar (Antananarivo) Swaziland (Mbabane) Ambassador: John Blane Ambassador: Patrick Gates Lynch Ambassador: Harvey F. Nelson, Jr. Comoros (Moroni) · Malawi (Lilongwe) Tanzania (Dar es Salaam) Relations managed from U.S. Ambassador: Weston Adams Ambassador: Donald K. -

ENABLING a DICTATOR the United States and Chad’S Hissène Habré 1982-1990 WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS ENABLING A DICTATOR The United States and Chad’s Hissène Habré 1982-1990 WATCH Enabling a Dictator The United States and Chad’s Hissène Habré 1982-1990 Copyright © 2016 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-33573 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JUNE 2016 ISBN: 978-1-6231-33573 Enabling a Dictator The United States and Chad’s Hissène Habré 1982-1990 Summary ............................................................................................................................ 1 Methodology ...................................................................................................................... 7 Early Years and Warning Signs of Future Atrocities ............................................................. 9 Bringing Hissène -

Faa4ec32be19cf69c125777d

The FY 1987 Annual Report of the Office of U.S. Office of US Foreign Disaster Assistance was researched, Foreign Disaster Assistance written, and produced by Cynthia Davis, Mark W. Hall, Faye Henderson, Waverly Jackson, Dennis Agency for King, Wesley Mossburg, Joseph O'Connor, Carol lnternatiollal Skowron, Kimberly S. Caulfield Vasconez, and Development Beverly Youmans of Evaluation Technologies In- corporated, Arlington, Virginia, 22201, under Washington, DC 20523 contract number OTR-0000-C-00-3345-00. 1 BEST AVAILABLE CCPY Message from the Director .......................................................................................................................................7 Disaster Preparedness. Mitigation. and Training .................................................................................................... 8 Summary of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance ....................................................................................................... 14 OFDA Emergency Response: Prior-Year (FY 1984. 1985. and 1986) and Non-Declared Disasters ............................................................... 20 FY 1987 Disasters Asia and the Pacific ................................................................................................................................................ 23 Bangladesh Floods ................................................................................................................................................ 24 China Fire .............................................................................................................................................................. -

Evaluating the EU's Response to the US Global Gag Rule

STUDY Requested by the FEMM committee Evaluating the EU’s Response to the US Global Gag Rule State of play and challenges ahead Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs Directorate-General for Internal Policies PE 621.927- September 2020 EN Evaluating the EU’s response to the US Global Gag Rule State of play and challenges ahead Abstract This study commissioned by the European Parliament’s Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs at the request of the FEMM Committee, maps out the challenges the European Union faces in promoting sexual and reproductive health and rights and the prevention of gender based violence in its external action, especially in providing aid to developing countries against the backdrop of US Global Gag Rules. This document was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Women's Rights and Gender Equality. AUTHORS Clara COTRONEO, European Institute of Public Administration Petra JENEY, European Institute of Public Administration The authors wish to express their gratitude to Mathias DELMEIRE and Olivia BROWN for their research assistance in completing this study. ADMINISTRATOR RESPONSIBLE Martina SCHONARD EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Sandrina MARCUZZO LINGUISTIC VERSIONS Original: EN ABOUT THE EDITOR Policy departments provide in-house and external expertise to support EP committees and other parliamentary bodies in shaping legislation and exercising democratic scrutiny over EU internal policies. To contact the Policy Department or to subscribe for updates, please write to: Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs European Parliament B-1047 Brussels Email: [email protected] Manuscript completed in September 2020 © European Union, 2020 This document is available on the internet at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/supporting-analyses DISCLAIMER AND COPYRIGHT The opinions expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the European Parliament. -

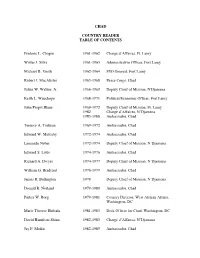

Table of Contents

CHAD COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Frederic L. Chapin 1961-1962 Chargé d’Affaires, Ft. Lamy Walter J. Silva 1961-1963 Administrative Officer, Fort Lamy Michael B. Smith 1962-1964 FSO General, Fort Lamy Robert J. MacAlister 1965-1968 Peace Corps, Chad Julius W. Walker, Jr. 1966-1969 Deputy Chief of Mission, N'Djamena Keith L. Wauchope 1968-1971 Political/Economic Officer, Fort Lamy John Propst Blane 1969-1972 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ft. Lamy 1982 Charge d’Affaires, N’Djamena 1985-1988 Ambassador, Chad Terence A. Todman 1969-1972 Ambassador, Chad Edward W. Mulcahy 1972-1974 Ambassador, Chad Leonardo Neher 1972-1974 Deputy Chief of Mission, N’Djamena Edward S. Little 1974-1976 Ambassador, Chad Richard A. Dwyer 1974-1977 Deputy Chief of Mission, N’Djamena William G. Bradford 1976-1979 Ambassador, Chad James R. Bullington 1979 Deputy Chief of Mission, N’Djamena Donald R. Norland 1979-1980 Ambassador, Chad Parker W. Borg 1979-1981 Country Director, West African Affairs, Washington, DC Marie Therese Huhtala 1981-1983 Desk Officer for Chad, Washington, DC David Hamilton Shinn 1982-1983 Chargé d’Affaires, N’Djamena Jay P. Moffat 1982-1985 Ambassador, Chad Richard W. Bogosian 1990-1992 Ambassador, Chad Franklin E. Huffman 1999-2000 Public Affairs Officer, N’Djamena Christopher E. Goldthwait 1999-2004 Ambassador, Chad FREDERIC L. CHAPIN Chargé d’Affaires Ft. Lamy (1961-1962) Ambassador Frederic L. Chapin joined the Foreign Service in 1952. His career included posts in Austria, Nicaragua, Brazil, El Salvador, and ambassadorships to Ethiopia and Guatemala. Ambassador Chapin was interviewed by Ambassador Horace G. Torbert in 1989.