Arxiv:1705.04061V1 [Physics.Optics] 11 May 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cool in the Kitchen: Radiation, Conduction, and the Newton “Hot Block” Experiment

Cool in the Kitchen: Radiation, Conduction, and the Newton “Hot Block” Experiment Mark P. Silverman and Christopher R. Silverman he rate at which an object cools down Our curiosity was aroused. How good an Tgives valuable information about the approximation to reality is Newton’s law— mechanisms of heat loss and the thermal prop- and what in any event determines whether the erties of the material. In general, heat loss temperature of the hot object is too high? occurs by one or more of the following four Furthermore, although Newton’s name is processes: (a) conduction, (b) convection, (c) readily associated with his laws of motion, evaporation, and (d) radiation. law of gravity, and various optical phenomena In conduction, heat is transferred through a and apparatus, it does not usually appear in medium by the collisional encounters of ther- discussions of thermal phenomena. Indeed, mally excited molecules vibrating about their apart from this one instance, a search through equilibrium positions, or, in the case of met- a score or more of history of science books als, by mobile, unbound electrons; only ener- and thermal physics books at various levels of gy, not bulk matter itself, moves through the instruction produced but one other circum- Mark P. Silverman is material. Convection, by contrast, refers to the stance for noting Newton’s name—and that Professor of Physics at Trinity College and former transfer of heat through the action of a moving was his failure to recognize the adiabatic 3 Joliot Professor of Physics fluid; in free or natural convection, the motion nature of sound propagation in air. -

Consistent Pitch Height Forms: a Commentary on Daniel Muzzulini's Contribution Isaac Newton's Microtonal Approach To

Consistent Pitch Height Forms: A commentary on Daniel Muzzulini’s contribution Isaac Newton’s Microtonal Approach to Just Intonation THOMAS NOLL[1] Escola Superior de Música de Catalunya, Departament de Teoria, Composició i Direcció ABSTRACT: This text revisits selected aspects of Muzzulini’s article and reformulates them on the basis of a three-dimensional interval space E and its dual E*. The pitch height of just intonation is conceived as an element h of the dual space. From octave-fifth-third coordinates it becomes transformed into chromatic coordinates. The dual chromatic basis is spanned by the duals a* of a minor second a and the duals b* and c* of two kinds of augmented primes b and c. Then for every natural number n a modified pitch height form hn is derived from h by augmenting its coordinates with the factor n, followed by rounding to nearest integers. Of particular interest are the octave-consitent forms hn mapping the octave to the value n. The three forms hn for n = 612, 118, 53 (yielding smallest deviations from the respective values of n h) form the Muzzulini basis of E*. The respective transformation matrix T* between the coordinate representations of linear forms in the Muzzulini basis and the dual chromatic basis is unimodular and a Pisot matrix with the dominant eigen-co-vector very close to h. Certain selections of the linear forms hn are displayed in Muzzuli coordinates as ball-like point clouds within a suitable cuboid containing the origin. As an open problem remains the estimation of the musical relevance of Newton’s chromatic mode, and chromatic modes in general. -

How Cold Is Cold: What Is Temperature?

How_Cold_is_Cold:_What_is_Temperature? Hi. My name is Rick McMaster and I work at IBM in Austin, Texas. I'm the STEM advocate and known locally as Dr. Kold because of the work that I do with schools in central Texas. Think about this question. Was it cold today when you came to school? Was it hot? We'll come back to that shortly, but let's start with something that I think we would all agree is cold, ice. Here's a picture of a big piece of ice. An iceberg, in fact. Now take a few minutes to discuss how much of the iceberg you see above the water, and why this happens. Welcome back. The density of water is about 0.92 grams per cubic centimeter, and sea water about 1.025. If we divide the first by the second, you see that about 90% of the iceberg is below the surface, something for a ship to watch out for. Why did we start with density and not temperature? Density is something that's a much more common experience. If something floats in water, it's less dense than water. If it sinks, it's more dense. That can't be argued. Let's take a little more time to talk about water and ice because it will be important later. So why is ice less dense than water? The solid form of water forms hexagonal crystals with the Hydrogen atoms shown in white, forming bonds with neighboring Oxygen atoms in red. With the water molecules no longer able to move readily, the ice is less dense and the iceberg floats. -

Using Math to Understand Our World Project 1 Measuring Temperature & Newton’S Law of Cooling

Using Math to Understand Our World Project 1 Measuring Temperature & Newton’s Law of Cooling 1 Instructions Read through the project and work through all the questions. It is important that you work through everything so that you can understand all the issues. But you do not have to hand in all of your answers. To see which answers to hand in, refer to the “What to Hand In” sheet. I have tried to put in boldface all questions in the text that also appear in the “What to Hand In” sheet. Note that there may also be a few questions on the “What to Hand In” sheet that are not explicitly stated in the project, but which you will be able to answer after working through the project. 2 Introduction Isaac Newton is often said to have been the greatest mathematician and scientist ever, and may very well have been. Everyone knows the story of Newton and the apple tree. You’ve probably also heard of Newton’s Law of Inertia: An object at rest tends to stay at rest, an object in motion tends to stay in motion. You may even have heard of Newton’s Second Law, F = ma (Force = mass ∗ acceleration ). Newton invented calculus, developed laws of gravity, discovered that white light is made up of many colors, measured the speed of sound, developed the foundations of mechanics (including the Laws above) and so on. Newton probably added more to the understanding of nature than any other person, ever. Later in his life, Newton was interested in temperature. -

VI. the Colours of the Atmosphere Considered with Reference to a Previous Paper “On the Colour of Steam Under Certain Circumstances.”

Philosophical Magazine Series 3 ISSN: 1941-5966 (Print) 1941-5974 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tphm14 VI. The colours of the atmosphere considered with reference to a previous paper “On the colour of steam under certain circumstances.” James D. Forbes Esq. F. R. SS. L. & Ed. To cite this article: James D. Forbes Esq. F. R. SS. L. & Ed. (1839) VI. The colours of the atmosphere considered with reference to a previous paper “On the colour of steam under certain circumstances.” , Philosophical Magazine Series 3, 15:93, 25-37, DOI: 10.1080/14786443908649817 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14786443908649817 Published online: 01 Jun 2009. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 3 View related articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=3phm20 Download by: [Universite Laval] Date: 27 June 2016, At: 10:33 Professor Forbes on the Colours of the/ltmosphere. 25 But it appears to me that the powers and riehes of these extraordinary districts remain vet to be fully developed. They exhibit an immense number of mighty steam-engines, furnished by nature at no cost, and applicable to the produc- tion of an infinite variety of objects. In the progress of time this vast machinery of heat and force will probably become the moving central point of extensive manufacturing establish- ments. The steam, which has been so ingeniously applied to the concentration and evaporation of the boracic acid, will probably hereafter, instead of wasting itself in the air, be em- ployed to move huge engines, which will be directed to the infinite variety of production which engages the attention of labouring and intelligent artisans; and thus, in the course of time, there can be little doubt, that these lagoons, which were fled fi'om as objects of danger and terror by uninstructed man, will gather round them a large intelligent population, and beeome sources of prosperity to innumerable individuals through countless generations. -

Natures Forces Simple Machines

ELEMENTARY SCIENCE PROGRAM MATH, SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY EDUCATION A Collection of Learning Experiences NATURES FORCES SIMPLE MACHINES Nature’s Forces Simple Machines Student Activity Book Name__________________________________________________________ This learning experience activity book is yours to keep. Please put your name on it now. This activity book should contain your observations of and results from your experiments. When performing experiments, ask your teacher for any additional materials you may need. TABLE OF CONTENTS Activity Sheet for L.E. #1 - Measuring Mass ...........................................................2-3 Activity Sheet for L.E. #2 - Measuring Weight.........................................................4 Activity Sheet for L.E. #3 - Measuring Force...........................................................5-8 Activity Sheet for L.E. #4 - Force, Weight and Mass...............................................9-11 Activity Sheet for L.E. #5 - Gravity – Gravity Everywhere .......................................12-17 Activity Sheet for L.E. #6 - Unseen Forces .............................................................18-23 Activity Sheet for L.E. #7 - Inclined Plane ...............................................................24-31 Activity Sheet for L.E. #8 - Wedge ..........................................................................32-33 Activity Sheet for L.E #9 - Screw.............................................................................34-35 Activity Sheet for L.E. #10 - Levers.........................................................................36-41 -

A Selection of New Arrivals September 2017

A selection of new arrivals September 2017 Rare and important books & manuscripts in science and medicine, by Christian Westergaard. Flæsketorvet 68 – 1711 København V – Denmark Cell: (+45)27628014 www.sophiararebooks.com AMPERE, Andre-Marie. Mémoire. INSCRIBED BY AMPÈRE TO FARADAY AMPÈRE, André-Marie. Mémoire sur l’action mutuelle d’un conducteur voltaïque et d’un aimant. Offprint from Nouveaux Mémoires de l’Académie royale des sciences et belles-lettres de Bruxelles, tome IV, 1827. Bound with 18 other pamphlets (listed below). [Colophon:] Brussels: Hayez, Imprimeur de l’Académie Royale, 1827. $38,000 4to (265 x 205 mm). Contemporary quarter-cloth and plain boards (very worn and broken, with most of the spine missing), entirely unrestored. Preserved in a custom cloth box. First edition of the very rare offprint, with the most desirable imaginable provenance: this copy is inscribed by Ampère to Michael Faraday. It thus links the two great founders of electromagnetism, following its discovery by Hans Christian Oersted (1777-1851) in April 1820. The discovery by Ampère (1775-1836), late in the same year, of the force acting between current-carrying conductors was followed a year later by Faraday’s (1791-1867) first great discovery, that of electromagnetic rotation, the first conversion of electrical into mechanical energy. This development was a challenge to Ampère’s mathematically formulated explanation of electromagnetism as a manifestation of currents of electrical fluids surrounding ‘electrodynamic’ molecules; indeed, Faraday directly criticised Ampère’s theory, preferring his own explanation in terms of ‘lines of force’ (which had to wait for James Clerk Maxwell (1831-79) for a precise mathematical formulation). -

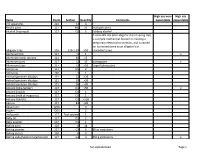

Full-Alphabetized Page 1 Items Room Section Quantity Comments High

High use non- High use Items Room Section Quantity Comments expendable expendable 2-D apparatus 121 14 3 Acrylic paint 117 M0 >5 multiple colors Alcohol (isopropyl) 117 D2 6 rubbing alcohol A crocodile clip (also alligator clip or spring clip) is a simple mechanical device for creating a temporary electrical connection, and is named for its resemblance to an alligator's or Alligator clips 116 116-1-29 >10 crocodile's Jaws Aluminum foil 117 I1 1 x Aluminum mesh screens 121 40 >5 Aluminum pans 117 L2 15 baking pans x Aluminum trays 117 L2 >10 larger baking pans Ammonia 117 D5 2 Ammonia 120 3 1 Animal specimen displays 121 33 >20 Animal specimen displays 121 35 >20 Animal specimen displays 121 36 >20 Antacid (Alka-Seltzer) 117 D1 >50 x Antacid (liQuid) 117 D1 1 Antacid (milk of magnesia) 117 D1 1 Antacid (tablets) 117 D1 >100 Aprons 117 B1 >20 AQuariums 120A 3 Augers 120A 2 Awl punch 117 Tool cabinet 1 Baby oil 117 D1 2 Baby powder 117 D1 1 Baking pans 120 6 14 Baking powder 117 G3 6 10 oz containers Baking sheets 120 6 5 Baking soda (Sodium bicarbonate) 117 G3 3 450 g containers x full-alphabetized Page 1 High use non- High use Items Room Section Quantity Comments expendable expendable Baking soda (Sodium bicarbonate) 121 42 1 x Balance scales 120 10 14 Balloons 116 116-1-8 >50 x Balloons 117 B3 >20 x Balls (golf) 117 B7 x Balls (golf) 121 121-1-25-28 >10 Balls (large rubber play) 117 O0 5 large bouncing balls Balls (ping pong) 117 B7 x Balls (ping pong) 121 121-1-25-28 >20 x Balls (racQuet balls) 117 B7 x Balls (racQuet balls) 121 121-1-25-28 -

Playing in Newton's Lab Original

Title: Playing in Newton's Lab Original: June 15, 2010 Revision: Authors: Buzz Putnam Appropriate Level: Regents, Honors Physics Abstract: There are many misconceptions for students in the world of Physics and one of the most common is the relationship between weight and mass. Throughout a student’s high school science courses, the terms, Mass and Weight, are used by educators without regard to their actual conceptual meanings and the two become a “gray” area in the students’ mind. This confusion between Weight and Mass is carried with the student throughout high school until he or she enrolls in a Physics course, where the distinction is made between the two terms. In this lab, the student will determine the Mass of objects utilizing three different methods without the conventional “weighing” technique that is the usual protocol for finding Mass in the Physics classroom. Using Newton’s 1st and 2nd Laws, the Mass of the object(s) will be found by student experiment, rather than using a Newton scale. As a 4th exercise, students will use a hands-on technique to conceptualize Newton’s Law of Universal Gravitation. Time Required: Two 40 minute class periods Center for Nanoscale Systems Institute for Physics Teachers (CIPT) 632 Clark Hall, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853 www.cns.cornell.edu/cipt/ [email protected] NY Standards Met: Key Idea 2: Beyond the use of reasoning and consensus, scientific inquiry involves the testing of proposed explanations involving the use of conventional techniques and procedures and usually requiring considerable ingenuity. S2.1 Devise ways of making observations to test proposed explanations. -

C:\Data\WP\F\196-Physics\196 Internet.Wpd

Jonathan A. Hill, Bookseller, Inc. 325 West End Avenue, Apt. 10B New York City, New York, 10023-8145 Tel: 646 827-0724 Fax: 212 496-9182 E-mail: [email protected] Catalogue 196 Proofs Physics, Mechanics, Engineering, Technology, & Electricity 2 JONATHAN A. HILL Catalogue 196 The Horblit Copy 1. ACADÉMIE ROYALE DES SCIENCES, Paris. Mémoires...Année 1823. Tome VI. Two folding engraved plates. 3 p.l., clxxvi, [3], 612 pp. Large 4to, orig. printed wrappers (rather frayed), uncut. Paris: Firmin Didot, 1827. $2500.00 “Of particular importance to this collection is Navier’s ‘Mémoire sur les lois du mouvement des fluides.’ This classic paper on fluid mechanics, contains his calculations about fluid flow, and gives his equations for motion of a viscous fluid. Also discovered by Stokes, these calculations are known today as the Navier-Stokes Equations. Navier analyzed the motion of a fluid in much the same fashion as Euler, but considered in addition a hypothetical attraction or repulsion between adjacent molecules . “Also of importance is Ampere’s ‘Mémoire sur la théorie mathématique des phénomènes électro-dynamique, uniquement déduite de l’expérience...’ which seeks to provide mathematical foundations for the relationship he had discovered between the phenomena of electricity and magnetism. His discovery resulted from a series of ingenious experiments which are described in the text. This represents the first formulation of the laws of the action of electric currents, and the memoir can be seen as the cornerstone of electrodynamics. This brings together his memoirs read before the Academy 26 December 1820, 10 June 1822, CATALOGUE ONE HUNDRED & NINETY–SIX 3 22 December 1823, 12 September and 23 November of 1825 . -

Mass, Density, and Properties of Matter OL Mass, Density, and Properties of Matter on Level

Science Theme: Order and Organization y, Science Inquiry and Application nsit Strand: Physical Science De Topic: Matter and Motion Mass, ies opert English Language Arts d Pr Strand: Reading: Informational Text an r Topic: Key Ideas and Details te Craft and Structure of Mat l On Leve FOCUS curriculum Curriculum materials for your content standards 33 Milford Drive, Suite 1, Hudson, OH 44236 866-315-7880 • www.focuscurriculum.com The ultra dense remains of a massive star light up surrounding gases. (Image: NASA/CXC/SAO/P Slane et al) MasFs,o Dcuesn osnit yO, ahniod SPtraonpdearrtides s of Matter AbOovne Level 2010 Content Statements Science 6 Theme: Order and Organization Science Inquiry and Application: Design and conduct a scientific investigation; Analyze and interpret data; Think critically and logically to connect evidence and explanations.; Communicate scientific procedures and explanations. Strand: Physical Science Topic: Matter and Motion Content Statements: All matter is made up of small particles called atoms. 2 Mass, Density, and Properties of Matter OL Mass, Density, and Properties of Matter On Level 2010 Common Core State Standards English Language Arts 6 Strand: Reading: Informational Text Topic: Key Ideas and Details Standard Statements: Cite textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text.; Determine a central idea of a text and how it is con - veyed through particular details; provide a summary of the text distinct from personal opinions or judgments. Topic: Craft and Structure Standard Statement: Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including figurative, connota - tive, and technical meanings. -

1 Radiation, Conduction, and the Way Objects Cool: Newton's 'Hot Block

Radiation, Conduction, and the Way Objects Cool: Newton’s ‘Hot Block’ Experiment 300 Years Later M. P. Silverman [Adapted from M. P. Silverman, A Universe of Atoms, An Atom in the Universe (Springer, 2002), initially published as a cover story in The Physics Teacher (2000)] When I had these points determined, in order to investigate the others, I heated a large enough block of iron until it was glowing, and taking it from the fire with a forceps while it was glowing I placed it at once in a cold place where the wind was constantly blowing… —Isaac Newton (A Scale of the Degrees of Heat, 1701) Summary In general, objects cool by one or more of four different processes: conduction, convection, evaporation, and radiation. While Master of the Royal Mint at a time well before the principles of thermodynamics were established, Isaac Newton published an anonymous paper creating a practical temperature scale based on the rate of cooling of an iron block. Some 300 years later my son and I performed variations of the ‘hot block’ experiment in our kitchen and found that ‘Newton’s Law of Cooling’ did not work well. Our own thermodynamically-derived law of cooling fits the data much better. ‘The Heat of a Little Kitchen Fire…’ The rate at which an object cools gives valuable information about the mechanisms of heat loss and the thermal properties of the material. In general, heat loss occurs by one or more of the following four processes: (a) conduction, (b) convection, (c) evaporation, and (d) radiation. In conduction heat is transferred through a medium by the collisional encounters of thermally excited molecules vibrating about their equilibrium positions, or, in the case of metals, by mobile, unbound electrons; only energy, not bulk matter itself, moves through the material.