Media Freedom in Serbia in 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medijska Kampanja Inicijative REKOM Izveštaj, 27

Medijska kampanja Inicijative REKOM Izveštaj, 27. mart – 03. avgust 2011. godine U periodu od 27. 03. do 03.08.2011. godine, u medijima u regionu bivše Jugoslavije o Inicijativi REKOM objavljeno je više od 610 tekstova. Većina tekstova prenose podršku Inicijativi REKOM. Inicijativa je imala veliku podrsku medija u Srbiji i Crnoj Gori, ignorisana je u javnim medijima u Hrvatskoj, a u medijima u Federaciji BiH bilo je negativnih priloga. 1. Oglašavanje u štampanim medijima i na Facebook-u Oglas REKOM, Daj potpis prikazan je na stranicama korisnika Facebook 14.565.215 puta, a posetilo ga je (kliknulo) 7.898 korisnika iz Albanije, Bosne i Hercegovine, Kosova, Hrvatske, Makedonije i Srbije. Druga oglasna kampanja su promo poruke preko sajta Neogen.rs. Promo poruke su poslate na adrese 428.121 korisnika baze podataka pomenutog sajta, 6.908 korisnika je pročitalo poruku i informisalo se o Inicijativi REKOM. 1.1. Srbija Oglas REKOM-Daj potpis 11.05.2011. Politika i Danas (plaćeni oglas) 12.05. 2011. Blic i Dnevnik (plaćeni oglas) 13.05.2011. Magyar Szo (plaćeni oglas) 19.05. 2011. Nin i Vreme (plaćeni oglas) 9.06.2011. Danas (plaćen oglas) 1.2. Bosna i Hercegovina 20.05. 2011. Oslobođenje i Dnevni list (plaćeni oglas) 25.05.2011. Oslobođenje (plaćeni oglas) 26.05.2011. BH Dani i Slobodna Bosna (plaćeni oglas) 27.05.2011. Oslobođenje i Dnevni list (plaćeni oglas) 1.06. 2011. Oslobođenje (plaćeni oglas) 1.3. Hrvatska 29.04.2011. Tjednik Novosti (gratis) 30.04.2011. Novi list (gratis) 06.05.2011. Tjednik Novosti (gratis) 07.05.2011. Novi list (gratis) 13.05.2011. -

Dragana Mašović

FACTA UNIVERSITATIS Series: Philosophy and Sociology Vol. 2, No 8, 2001, pp. 545 - 555 THE ROMANIES IN SERBIAN (DAILY) PRESS UDC 316.334.52:070(=914.99) Dragana Mašović Faculty of Philosophy, Niš Abstract. The paper deals with the presence of Romanies' concerns in Serbian daily press. More precisely, it tries to confirm the assumption that not enough space is devoted to the issue as evident in a small-scale analysis done on seven daily papers during the sample period of a week. The results show that not only mere absence of Romanies' issues is the key problem. Even more important are the ways in which the editorial startegy and the language used in the published articles turn out to be (when unbiased and non-trivial) indirect, allusive and "imbued with promises and optimism" so far as the presumed difficulties and problems of the Romanies are concerned. Thus they seem to avoid facing the reality as it is. Key Words: Romanies, Serbian daily press INTRODUCTION In Mary Woolstonecraft's Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1972) there is an urgent imperative mentioned that can also be applied to the issue of Romanies presence in our press. Namely, she suggested that "in the present state of society it appears necessary to go back to first principles in search of the most simple truths, and to dispute with some prevailing prejudice every inch of ground." More precisely, in the case of the Romanies' presence in the press the question to be asked is what would be the "first principles" that Woolstonecraft refers to? No doubt that in this context they refer to what has always been considered the very basis of every democratic, open-minded and tolerant society, that is, the true equality of all the citizens as reflected in every aspect of the society that proclaims itself to be multi-cultural. -

Media Watch Serbia1 Print Media Monitoring

Media Watch Serbia1 Print Media Monitoring METHODOLOGY The analysis of the daily press from the viewpoint of the observance of generally accepted ethical norms is based on a structural quality analysis of the contents of selected newspaper articles. The monitoring includes eight dailies: Politika, Danas, Vecernje novosti, Blic, Glas javnosti, Kurir, Balkan and Internacional. Four weeklies are also the subject of the analysis: Vreme, NIN, Evropa and Nedeljni Telegraf. The basic research question requiring a reply is the following: What are the most frequent forms of the violation of the generally accepted ethical norms and standards in the Serbian press? The previously determined and defined categories of professional reporting are used as the unit of the analysis in the analysis of ethical structure of reporting. The texts do not identify all the categories but the dominant ones only, three being the maximum. The results of the analysis do not refer to the space they take or the frequency of their appearances but stress the ethical norms mostly violated and those which represent the most obvious abuse of public writing by the journalists. The study will not only point out typical or representative cases of non-ethical reporting but positive examples as well whereas individual non- standard cases of the violation of the professional ethics will be underlined in particular. Finally, at the end of each monitoring period, a detailed quality study of selected articles will provide a deep analysis of the monitored topics and cases. 1 The Media Watch Serbia Cultural Education and Development Project for Increasing Ethical and Legal Standards in Serbian Journalism is financed and supported by UNESCO. -

Authenticity in Electronic Dance Music in Serbia at the Turn of the Centuries

The Other by Itself: Authenticity in electronic dance music in Serbia at the turn of the centuries Inaugural dissertation submitted to attain the academic degree of Dr phil., to Department 07 – History and Cultural Studies at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz Irina Maksimović Belgrade Mainz 2016 Supervisor: Co-supervisor: Date of oral examination: May 10th 2017 Abstract Electronic dance music (shortly EDM) in Serbia was an authentic phenomenon of popular culture whose development went hand in hand with a socio-political situation in the country during the 1990s. After the disintegration of Yugoslavia in 1991 to the moment of the official end of communism in 2000, Serbia was experiencing turbulent situations. On one hand, it was one of the most difficult periods in contemporary history of the country. On the other – it was one of the most original. In that period, EDM officially made its entrance upon the stage of popular culture and began shaping the new scene. My explanation sheds light on the fact that a specific space and a particular time allow the authenticity of transposing a certain phenomenon from one context to another. Transposition of worldwide EDM culture in local environment in Serbia resulted in scene development during the 1990s, interesting DJ tracks and live performances. The other authenticity is the concept that led me to research. This concept is mostly inspired by the book “Death of the Image” by philosopher Milorad Belančić, who says that the image today is moved to the level of new screen and digital spaces. The other authenticity offers another interpretation of a work, or an event, while the criterion by which certain phenomena, based on pre-existing material can be noted is to be different, to stand out by their specificity in a new context. -

Civil-Military Features of the FRY

Civil-Military Features of the FRY 18. november 2002. - Dr Miroslav Hadzic Dr Miroslav Hadžić Faculty of Political Science Belgrade / Centre for Civil-Military Relations Occasional paper No.4 The direction of the profiling of civilian military relations in Serbia/FR Yugoslavia1 is determined by the situational circumstances and policies of the participants of different backgrounds and uneven strength. The present processes however, are the direct product of consequence of the disparate action of parties from the Democratic Opposition of Serbia (DOS) coalition, which have ruled the local political scene since the ousting of Milošević. It was their mediation that introduced the war and authoritarian heritage to the political scene, making it an obstacle for changing the encountered civil-military relations. The ongoing disputes within the DOS decrease, but also conceal the fundamental reasons for the lack of pro-democratic intervention of the new authorities in the civil-military domain. Numerous military and police incidents and affairs that have marked the post-October period in Serbia testify to this account.2 The incidents were used for political confrontation within the DOS instead as reasons for reform. This is why disputes regarding the statues of the military, police and secret services, as well as control of them have been reduced to the personal and/or political conflict between FRY President Vojislav Koštunica and Serbian Premier Zoran Djindjić.3 However, the analysis of the "personal equation" of the most powerful DOS leaders may reveal only differences in their political shade and intonation, but cannot reveal the fundamental reasons why Serbia has remained on the foundations of Milošević’s system. -

SERBIA Jovanka Matić and Dubravka Valić Nedeljković

SERBIA Jovanka Matić and Dubravka Valić Nedeljković porocilo.indb 327 20.5.2014 9:04:47 INTRODUCTION Serbia’s transition to democratic governance started in 2000. Reconstruction of the media system – aimed at developing free, independent and pluralistic media – was an important part of reform processes. After 13 years of democratisation eff orts, no one can argue that a new media system has not been put in place. Th e system is pluralistic; the media are predominantly in private ownership; the legal framework includes European democratic standards; broadcasting is regulated by bodies separated from executive state power; public service broadcasters have evolved from the former state-run radio and tel- evision company which acted as a pillar of the fallen autocratic regime. However, there is no public consensus that the changes have produced more positive than negative results. Th e media sector is liberalized but this has not brought a better-in- formed public. Media freedom has been expanded but it has endangered the concept of socially responsible journalism. Among about 1200 media outlets many have neither po- litical nor economic independence. Th e only industrial segments on the rise are the enter- tainment press and cable channels featuring reality shows and entertainment. Th e level of professionalism and reputation of journalists have been drastically reduced. Th e current media system suff ers from many weaknesses. Media legislation is incom- plete, inconsistent and outdated. Privatisation of state-owned media, stipulated as mandato- ry 10 years ago, is uncompleted. Th e media market is very poorly regulated resulting in dras- tically unequal conditions for state-owned and private media. -

Analiza Medijskog Tržišta U Srbij

Jačanje medijske slobode Analiza medijskog tržišta u Srbij Ipsos Strategic Marketing Avgust 2015. godine 1 Sadržaj: . Preporuke i zaključci . Metodologija . Osnovni nalazi (Executive Summary) . Tržište oglašavanja u Srbiji . Trend procene realne vrednosti TV tržišta za period 2008. – 2014 . Trend procene realne vrednosti radio tržišta za period 2008. – 2014 . Najveći oglašivači TV tržišta . Udeo televizijskih kuća u ukupnom TV tržištu oglašavanja . Internet tržište oglašavanja . Pregled medijskog tržišta Srbije . Televizija . Podaci o gledanosti TV stanica . Najgledanije TV emisije na ukupnom tržištu i po relevantnim tržištima u 2014. I 2015. godini . Profil gledalaca televizijskih stanica . RTS1 . TV Prva . TV Pink . TV B92 . TV Happy . TV Vojvodina 1 . Prosečna slušanost radija i gledanost televizije po satima . Radio . Udeo nacionalnih radio stanica u ukupnom auditorijumu . Prosečni dnevni auditorijum nacionalnih radio stanica . Prosečni nedeljni auditorijum nacionalnih radio stanica . Internet . Medijske navike korisnika radijskih i televizijskih programa . Glavni izvor informisanja – Opšta populacija . Glavni izvor informisanja podela po godinama . Učestalost gledanja TV programa . Procena vremena korišćenja različitih vrsta medija pre godinu dana i sada . Procena kvaliteta sadržaja razlicitih vrsta medija . Programski sadržaji i preferencije auditorijuma . Navike korišćenja lokalnih medija . Lokalni mediji: zadovoljstvo kvalitetom i količinom lokalnog sadržaja . Programi na jezicima nacionalnih manjina . Televizijski sadržaji prilagođeni osobama sa invaliditetom . Makroekonomska situacija i njen uticaj na medijsko tržište . Analiza poslovanja pružalaca medijskih usluga . Prilozi 2 Preporuke i zaključci 1. Programski sadržaji TV emitera: a. U ukpnoj programskoj ponudi se ne uočava nedostak sadržaja i. Programski sadržaj javnog servisa je blizak izrečenim potrebama građana i na duži rok on se pokazuje adekvatnim jer ujedno ima i najveće učešće u ukupnoj glednosti. -

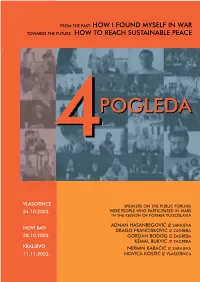

4 VIEWS. from the Past: How I Found Myself in War?

FROM THE PAST: HOW I FOUND MYSELF IN WAR TOWARDS THE FUTURE: HOW TO REACH SUSTAINABLE PEACE 44POGLEDPOGLEDAA VLASOTINCE SPEAKERS ON THE PUBLIC FORUMS 24.10.2003. WERE PEOPLE WHO PARTICIPATED IN WARS IN THE REGION OF FORMER YUGOSLAVIA ADNAN HASANBEGOVI] IZ SARAJEVA NOVI SAD DRAGO FRAN^I[KOVI] IZ ZAGREBA 28.10.2003. GORDAN BODOG IZ ZAGREBA KEMAL BUKVI] IZ ZAGREBA KRALJEVO NERMIN KARA^I] IZ SARAJEVA 11.11.2003. NOVICA KOSTI] IZ VLASOTINCA INITIATIVE AND ORGANISATION CENTAR ZA NENASILNU AKCIJU CENTRE FOR NONVIOLENT ACTION Office in Belgrade Office in Sarajevo Studentski trg 8, 11000 Beograd, SCG Radni~ka 104, 71000 Sarajevo, BiH Tel: +381 11 637-603, 637-661 Tel: +387 33 212-919, 267-880 Fax: +381 11 637-603 Fax: +387 33 212-919 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] www.nenasilje.org IN COOPERATION WITH UDRU@ENJE BORACA RATA 90. VLASOTINCE DRU[TVO ZA NENASILNU AKCIJU from Novi Sad OMLADINSKA ORGANIZACIJA KVART from Kraljevo Publication edited and articles written by activists of Centre for Nonviolent Action Adnan Hasanbegovi} Helena Rill Ivana Franovi} Milan Coli} Humljan Ned`ad Horozovi} Nenad Vukosavljevi} Sanja Deankovi} Tamara [midling About the public forums, the idea and the need Should we talk about the war? us, in whose name the wars had been lead protagonists are former soldiers, ‘Whatever happened it's all water and provoked. We carry our responsibility participants of the wars taking place in the under the bridge! It's everyone's fault. The because we have either supported creat- region of former Yugoslavia during the war is evil. -

OHR Bih Media Round-Up, 10/9/2002

OHR BiH Media Round-up, 10/9/2002 Print Media Headlines Oslobodjenje: FOSS Affair – mole in the top of the Federation Dnevni Avaz: Izetbegovic on FOSS report – Equating us with terrorists will not pass Jutarnje Novine: NDI poll – Silajdzic keeps trust of voters Nezavisne Novine: Two nights ago in Kozarac near Prijedor: Policeman wounded; Banja Luka: Nikola Miscevic detained Blic: Warner Blatter – Demographics never to be same again; Yugoslavia, the champion Glas Srpski: Two nights ago in Kozarac near Prijedor: Policeman wounded; Banja Luka: Nikola Miscevic detained Dnevni List: Expelled Drvar Croats denied Croatian documents Vecernji List: Yugoslav supporters go on rampage in the RS; Deputy Federation Finance Minister protests lottery RS Issues During a press conference following his meeting with representatives of the OHR and the World Bank about electric power distribution and payment of pensions, the RS Prime Minister, Mladen Ivanic, said that the RS government had nothing to do with the controversial Srebrenica report. “Firstly, this report was not officially published, it was presented by the media. The report never passed through official procedure. Just to remind you, the government bureau did present the report at a press conference after one part of the report was published in the media… The RS government will not endorse any report which would constitute its own, definitive view about the events. We know that what happened there was a crime…However, the final truth about Srebrenica ought to be presented by historians and experts, not by politicians.” (BHTV 1, FTV, RTRS, Oslobodjenje p. 9, Vecernji List p. 2, Blic p. -

Transatlantic Cooperation and the Prospects for Dialogue

Transatlantic Cooperation and the Prospects for Dialogue The Council for Inclusive Governance (CIG) organized on February 26, 2021 a discussion on trans-Atlantic cooperation and the Kosovo-Serbia dialogue for a group of politicians and civil society representatives from Kosovo and Serbia. Two CIG board members, former senior officials in the U.S. Department of State and the European Commission, took part as well. The meeting specifically addressed the effects of expected revitalized transatlantic cooperation now with President Joe Biden in office, the changes in Kosovo after Albin Kurti’s February 14 election victory, and the prospects of the Kosovo-Serbia dialogue in 2021. The following are a number of conclusions and recommendations based either on consensus or broad agreement. They do not necessarily represent the views of CIG and the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA), which supports CIG’s initiative on normalization between Kosovo and Serbia. The discussion was held under the Chatham House Rule. Conclusions and recommendations The change of governments in Kosovo and in the US are positive elements for the continuation of the dialogue. However, there are other pressing issues and reluctance both in Belgrade and in Pristina that make it almost impossible for the dialogue to achieve breakthrough this year. • The February 14 election outcome in Kosovo signaled a significant change both at the socio- political level and on the future of the dialogue with Serbia. For the first time since the negotiations with Serbia began in 2011, Kosovo will be represented by a leader who is openly saying that he will not yield to any international pressure to make “damaging agreements or compromises.” “However, this is not a principled position, but rather aimed at gaining personal political benefit,” a speaker, skeptical of Kurti’s stated objectives, said. -

A Pillar of Democracy on Shaky Ground

Media Programme SEE A Pillar of Democracy on Shaky Ground Public Service Media in South East Europe RECONNECTING WITH DATA CITIZENS TO BIG VALUES – FROM A Pillar of Democracy of Shaky on Ground A Pillar www.kas.de www.kas.dewww.kas.de Media Programme SEE A Pillar of Democracy on Shaky Ground Public Service Media in South East Europe www.kas.de Imprint Copyright © 2019 by Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Media Programme South East Europe Publisher Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. Authors Viktorija Car, Nadine Gogu, Liana Ionescu, Ilda Londo, Driton Qeriqi, Miroljub Radojković, Nataša Ružić, Dragan Sekulovski, Orlin Spassov, Romina Surugiu, Lejla Turčilo, Daphne Wolter Editors Darija Fabijanić, Hendrik Sittig Proofreading Boryana Desheva, Louisa Spencer Translation (Bulgarian, German, Montenegrin) Boryana Desheva, KERN AG, Tanja Luburić Opinion Poll Ipsos (Ivica Sokolovski), KAS Media Programme South East Europe (Darija Fabijanić) Layout and Design Velin Saramov Cover Illustration Dineta Saramova ISBN 978-3-95721-596-3 Disclaimer All rights reserved. Requests for review copies and other enquiries concerning this publication are to be sent to the publisher. The responsibility for facts, opinions and cross references to external sources in this publication rests exclusively with the contributors and their interpretations do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung. Table of Content Preface v Public Service Media and Its Future: Legitimacy in the Digital Age (the German case) 1 Survey on the Perception of Public Service -

Serbia Guidebook 2013

SERBIA PREFACE A visit to Serbia places one in the center of the Balkans, the 20th century's tinderbox of Europe, where two wars were fought as prelude to World War I and where the last decade of the century witnessed Europe's bloodiest conflict since World War II. Serbia chose democracy in the waning days before the 21st century formally dawned and is steadily transforming an open, democratic, free-market society. Serbia offers a countryside that is beautiful and diverse. The country's infrastructure, though over-burdened, is European. The general reaction of the local population is genuinely one of welcome. The local population is warm and focused on the future; assuming their rightful place in Europe. AREA, GEOGRAPHY, AND CLIMATE Serbia is located in the central part of the Balkan Peninsula and occupies 77,474square kilometers, an area slightly smaller than South Carolina. It borders Montenegro, Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina to the west, Hungary to the north, Romania and Bulgaria to the east, and Albania, Macedonia, and Kosovo to the south. Serbia's many waterway, road, rail, and telecommunications networks link Europe with Asia at a strategic intersection in southeastern Europe. Endowed with natural beauty, Serbia is rich in varied topography and climate. Three navigable rivers pass through Serbia: the Danube, Sava, and Tisa. The longest is the Danube, which flows for 588 of its 2,857-kilometer course through Serbia and meanders around the capital, Belgrade, on its way to Romania and the Black Sea. The fertile flatlands of the Panonian Plain distinguish Serbia's northern countryside, while the east flaunts dramatic limestone ranges and basins.