B2c1waring Prey Harbor Seals.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rapid Formation and Degradation of Barrier Spits in Areas with Low Rates of Littoral Drift*

Marine Geology, 49 (1982) 257-278 257 Elsevier Scientific Publishing Company, Amsterdam- Printed in The Netherlands RAPID FORMATION AND DEGRADATION OF BARRIER SPITS IN AREAS WITH LOW RATES OF LITTORAL DRIFT* D.G. AUBREY and A.G. GAINES, Jr. Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA 02543 (U.S.A.) (Received February 8, 1982; revised and accepted April 6, 1982) ABSTRACT Aubrey, D.G. and Gaines Jr., A.G., 1982. Rapid formation and degradation of barrier spits in areas with low rates of littoral drift. Mar. Geol., 49: 257-278. A small barrier beach exposed to low-energy waves and a small tidal range (0.7 m) along Nantucket Sound, Mass., has experienced a remarkable growth phase followed by rapid attrition during the past century. In a region of low longshore-transport rates, the barrier spit elongated approximately 1.5 km from 1844 to 1954, developing beyond the baymouth, parallel to the adjacent Nantucket Sound coast. Degradation of the barrier spit was initiated by a succession of hurricanes in 1954 (Carol, Edna and Hazel). A breach opened and stabilized near the bay end of the one kilometer long inlet channel, providing direct access for exchange of baywater with Nantucket Sound, and separating the barrier beach into two nearly equal limbs. The disconnected northeast limb migrated shorewards, beginning near the 1954 inlet and progressing northeastward, filling the relict inlet channel behind it. At present, about ten percent of the northeast limb is subaerial: the rest of the limb has completely filled the former channel and disappeared. The southwest limb of the barrier beach has migrated shoreward, but otherwise has not changed significantly since the breach. -

Summary of 2017 Massachusetts Piping Plover Census Data

SUMMARY OF THE 2017 MASSACHUSETTS PIPING PLOVER CENSUS Bill Byrne, MassWildlife SUMMARY OF THE 2017 MASSACHUSETTS PIPING PLOVER CENSUS ABSTRACT This report summarizes data on abundance, distribution, and reproductive success of Piping Plovers (Charadrius melodus) in Massachusetts during the 2017 breeding season. Observers reported breeding pairs of Piping Plovers present at 147 sites; 180 additional sites were surveyed at least once, but no breeding pairs were detected at them. The population increased 1.4% relative to 2016. The Index Count (statewide census conducted 1-9 June) was 633 pairs, and the Adjusted Total Count (estimated total number of breeding pairs statewide for the entire 2017 breeding season) was 650.5 pairs. A total of 688 chicks were reported fledged in 2017, for an overall productivity of 1.07 fledglings per pair, based on data from 98.4% of pairs. Prepared by: Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife 2 SUMMARY OF THE 2017 MASSACHUSETTS PIPING PLOVER CENSUS INTRODUCTION Piping Plovers are small, sand-colored shorebirds that nest on sandy beaches and dunes along the Atlantic Coast from North Carolina to Newfoundland. The U.S. Atlantic Coast population of Piping Plovers has been federally listed as Threatened, pursuant to the U.S. Endangered Species Act, since 1986. The species is also listed as Threatened by the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife pursuant to Massachusetts’ Endangered Species Act. Population monitoring is an integral part of recovery efforts for Atlantic Coast Piping Plovers (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1996, Hecht and Melvin 2009a, b). It allows wildlife managers to identify limiting factors, assess effects of management actions and regulatory protection, and track progress toward recovery. -

Massachusetts Ocean Management Plan

Massachusetts Ocean Management Plan Volume 2 Baseline Assessment and Science Framework December 2009 Introduction Volume 2 of the Massachusetts Ocean Management Plan focuses on the data and scientific aspects of the plan and its implementation. It includes these two separate documents: • Baseline Assessment of the Massachusetts Ocean Planning Area - This Oceans Act-mandated product includes information cataloging the current state of knowledge regarding human uses, natural resources, and other ecosystem factors in Massachusetts ocean waters. • Science Framework - This document provides a blueprint for ocean management- related science and research needs in Massachusetts, including priorities for the next five years. i Baseline Assessment of the Massachusetts Ocean Management Planning Area Acknowledgements The authors thank Emily Chambliss and Dan Sampson for their help in preparing Geographic Information System (GIS) data for presentation in the figures. We also thank Anne Donovan and Arden Miller, who helped with the editing and layout of this document. Special thanks go to Walter Barnhardt, Ed Bell, Michael Bothner, Erin Burke, Tay Evans, Deb Hadden, Dave Janik, Matt Liebman, Victor Mastone, Adrienne Pappal, Mark Rousseau, Tom Shields, Jan Smith, Page Valentine, John Weber, and Brad Wellock, who helped us write specific sections of this assessment. We are grateful to Wendy Leo, Peter Ralston, and Andrea Rex of the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority for data and assistance writing the water quality subchapter. Robert Buchsbaum, Becky Harris, Simon Perkins, and Wayne Petersen from Massachusetts Audubon provided expert advice on the avifauna subchapter. Kevin Brander, David Burns, and Kathleen Keohane from the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection and Robin Pearlman from the U.S. -

Systematics of North Pacific Sand Lances of the Genus Ammodytes Based on Molecular and Morphological Evidence, with the Descrip

12 9 Abstract—The systematic status Systematics of North Pacific sand lances of of North Pacific sand lances (ge- nus Ammodytes) was assessed from the genus Ammodytes based on molecular and mitochondrial DNA (cytochrome oxidase c subunit 1) sequence data morphological evidence, with the description of and morphological data to identify a new species from Japan the number of species in the North Pacific Ocean and its fringing seas. Although only 2 species, Ammodytes James W. Orr (contact author)1 hexapterus and A. personatus, have Sharon Wildes2 been considered valid in the region, Yoshiaki Kai3 haplotype networks and trees con- structed with maximum parsimony Nate Raring1 and genetic distance (neighbor- T. Nakabo4 joining) methods revealed 4 highly Oleg Katugin5 divergent monophyletic clades that 2 clearly represent 4 species of Ammo- Jeff Guyon dytes in the North Pacific region. On the basis of our material and com- Email address for contact author: [email protected] parisons with sequence data report- ed in online databases, A. personatus 1 Resource Assessment and Conservation 3 Maizuru Fisheries Research Station is found throughout the eastern Engineering Division Field Science Education and Research Center North Pacific Ocean, Gulf of Alaska, Alaska Fisheries Science Center Kyoto University Aleutian Islands, and the eastern National Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA Nagahama, Maizuru Bering Sea where it co-occurs with 7600 Sand Point Way NE Kyoto 625-0086, Japan a northwestern Arctic species, A. Seattle, Washington 98115-6349 4 The -

Trachiniformes, Ammodytidae)

RESEARCH ARTICLE New insight into hybridization and unidirectional introgression between Ammodytes japonicus and Ammodytes heian (Trachiniformes, Ammodytidae) Jin-Koo Kim1*, Seung Eun Bae1, Soo Jeong Lee1,2, Moon Geun Yoon3 1 Department of Marine Biology, Pukyong National University, Busan, Korea, 2 Fisheries Resources and Environment Division, East Sea Fisheries Research Institute, National Institute of Fisheries Science, a1111111111 Gangnung, Korea, 3 Marine Biodiversity Institute of Korea, Seocheon-gun, Chungcheongnam-do, Korea a1111111111 a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract Based on northern (NOL) and southern (SOL) mitochondrial lineages, recently, it proposed the new species Ammodytes heian and revived the species name Ammodytes japonicus to OPEN ACCESS describe sand lances from the northwestern Pacific Ocean. This study used molecular Citation: Kim J-K, Bae SE, Lee SJ, Yoon MG methods to investigate genetic relationships between the two sand lance species in Korea (2017) New insight into hybridization and and Japan. In total, 154 specimens were collected from four locations in Korea (Baeng- unidirectional introgression between Ammodytes japonicus and Ammodytes heian (Trachiniformes, nyeongdo in the Yellow Sea, Tongyeong in the Korean Strait, and Jumunjin and Gijang in Ammodytidae). PLoS ONE 12(6): e0178001. the East Sea), and 50 specimens were collected from a single location in Japan (Wakkanai https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0178001 in the Okhotsk Sea). Mitochondrial DNA analysis demonstrated that the individuals from Editor: Tzen-Yuh Chiang, National Cheng Kung Baengnyeongdo and Tongyeong all belonged to the SOL, whereas those from Gijang, University, TAIWAN Jumunjin, and Wakkanai included individuals from both the NOL and SOL (over 75% NOL). -

Range Expansion and New Breeding Record for the Glossy Ibis in Massachusetts

RANGE EXPANSION AND NEW BREEDING RECORD FOR THE GLOSSY IBIS IN MASSACHUSETTS by Robert C. Humphrey The purpose of this paper is twofold: first, to give a brief summary of the history of the Glossy Ibis (Plegadis falcinellus) in North America and its northward expansion into Massachusetts; and second, to report on a new breeding location in the state. The Glossy Ibis is believed to be a fairly recent arrival in America from the Old World. Although very little literature exists as to how and when it arrived in the new world, Audubon (1967) noted the "first intimation" of this species in the United States as a bird shot in Maryland in 1817. By 1837 he referred to them as existing in vast numbers in Mexico and in flocks, but only as a summer resident, in Texas. Specimens appeared in the Boston Market around 1844. The first documentation of a live bird in Massachusetts was around 1850 (Audubon 1967, Bent 1926). By 1870 ibises were rare and local in the southeastern United States from Louisiana to Florida. Casual records existed north to Missouri, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, Ontario, and Nova Scotia (Pearson 1956). The first authentic breeding records occurred in Florida in the 1880s (Palmer 1962). The breeding range in this country was restricted to Texas and Florida for most of the first half of the 1900s. Ibises slowly expanded their breeding range into North and South Carolina in 1944 and 1947, respectively. A more rapid expansion took place in the 1950s. They first bred in New Jersey in 1955 and in Maryland in 1956 (Stewart 1957). -

Ammodytes Americanus

Maine 2015 Wildlife Action Plan Revision Report Date: January 13, 2016 Ammodytes americanus (American Sand Lance) Priority 3 Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) Class: Actinopterygii (Ray-finned Fishes) Order: Perciformes (Perch-like Fishes) Family: Ammodytidae (Sand Lances (sand Eels)) General comments: Maine DMR jurisdiction; NW Atlantic specialist = QC-RI at least No Species Conservation Range Maps Available for American Sand Lance SGCN Priority Ranking - Designation Criteria: Risk of Extirpation: NA State Special Concern or NMFS Species of Concern: NA Recent Significant Declines: NA Regional Endemic: NA High Regional Conservation Priority: Northeast Regional Synthesis (RSGCN): Responsibility: High, Concern: Very High High Climate Change Vulnerability: NA Understudied rare taxa: NA Historical: NA Culturally Significant: NA Habitats Assigned to American Sand Lance: Formation Name Intertidal Macrogroup Name Intertidal Water Column Habitat System Name: Embayment **Primary Habitat** Notes: larval stage Formation Name Subtidal Macrogroup Name Subtidal Coarse Gravel Bottom Habitat System Name: Coarse Gravel **Primary Habitat** Notes: adult and spawning (Oct - March) Macrogroup Name Subtidal Pelagic (Water Column) Habitat System Name: Nearshore **Primary Habitat** Notes: larval stage Habitat System Name: Offshore Notes: larval stage Macrogroup Name Subtidal Sand Bottom Habitat System Name: Sand Bottom Macrogroup - Unknown Habitat System **Primary Habitat** Notes: adult and spawning (Oct - March) Stressors Assigned to American Sand Lance: No Stressors Currently Assigned to American Sand Lance or other Priority 3 SGCN. Species Level Conservation Actions Assigned to American Sand Lance: No Species Specific Conservation Actions Currently Assigned to American Sand Lance or other Priority 3 SGCN. Guild Level Conservation Actions: This Species is currently not attributed to a guild. -

Systematic List of the Romanian Vertebrate Fauna

Travaux du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle © Décembre Vol. LIII pp. 377–411 «Grigore Antipa» 2010 DOI: 10.2478/v10191-010-0028-1 SYSTEMATIC LIST OF THE ROMANIAN VERTEBRATE FAUNA DUMITRU MURARIU Abstract. Compiling different bibliographical sources, a total of 732 taxa of specific and subspecific order remained. It is about the six large vertebrate classes of Romanian fauna. The first class (Cyclostomata) is represented by only four species, and Pisces (here considered super-class) – by 184 taxa. The rest of 544 taxa belong to Tetrapoda super-class which includes the other four vertebrate classes: Amphibia (20 taxa); Reptilia (31); Aves (382) and Mammalia (110 taxa). Résumé. Cette contribution à la systématique des vertébrés de Roumanie s’adresse à tous ceux qui sont intéressés par la zoologie en général et par la classification de ce groupe en spécial. Elle représente le début d’une thème de confrontation des opinions des spécialistes du domaine, ayant pour but final d’offrir aux élèves, aux étudiants, aux professeurs de biologie ainsi qu’à tous ceux intéressés, une synthèse actualisée de la classification des vertébrés de Roumanie. En compilant différentes sources bibliographiques, on a retenu un total de plus de 732 taxons d’ordre spécifique et sous-spécifique. Il s’agît des six grandes classes de vertébrés. La première classe (Cyclostomata) est représentée dans la faune de Roumanie par quatre espèces, tandis que Pisces (considérée ici au niveau de surclasse) l’est par 184 taxons. Le reste de 544 taxons font partie d’une autre surclasse (Tetrapoda) qui réunit les autres quatre classes de vertébrés: Amphibia (20 taxons); Reptilia (31); Aves (382) et Mammalia (110 taxons). -

What's Next After the Red-Footed Falcon? Predictions of Future

What’s Next After the Red-footed Falcon? Predictions of Future Vagrants in Massachusetts Robert H. Stymeist and Jeremiah R. Trimble 1990 Predictions Revisited It has been nearly fifteen years since Dick Forster and seven other well-known state birders tried to predict which would be the next ten new species of birds to appear in Massachusetts. In the June 1990 issue of Bird Observer [18 (3), pp.149-154] Forster published his results. Nearly forty species received at least one top-ten vote, and another fifteen received votes as “runners-up.” Four of the species ranked at the top of that list have now been recorded in Massachusetts as follows: Cave Swallow (#2): This species, which has become routine in the fall in New Jersey, was long expected in Massachusetts. Following reports of Cave Swallows in Connecticut and Rhode Island, it was finally added to the state list on November 14, 2003, when two individuals were seen in Orleans. Less than two weeks later on November 27 a single individual was seen in nearby Chatham. Ross’s Goose (#4): Population increases and range shift made it only a matter of time before this species landed in Massachusetts. Two birds were discovered in a flock of Snow Geese in Sunderland, May 25-26, 1997. Another individual was seen in Chilmark October 14-22, 2001, and a third report from Turners Falls October 21-25, 2004, is pending a decision from the Massachusetts Avian Records Committee (MARC). Lazuli Bunting (#7): Although it often wanders east of its territory to the Midwestern states, Lazuli Bunting has only been recorded once or twice in the northeast. -

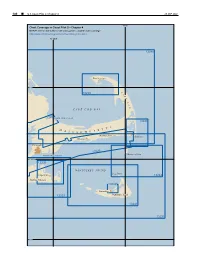

Outer Cape Cod and Nantucket Sound

186 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 2, Chapter 4 26 SEP 2021 70°W Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 2—Chapter 4 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 70°30'W 13246 Provincetown 42°N C 13249 A P E C O D CAPE COD BAY 13229 CAPE COD CANAL 13248 T S M E T A S S A C H U S Harwich Port Chatham Hyannis Falmouth 13229 Monomoy Point VINEYARD SOUND 41°30'N 13238 NANTUCKET SOUND Great Point Edgartown 13244 Martha’s Vineyard 13242 Nantucket 13233 Nantucket Island 13241 13237 41°N 26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 2, Chapter 4 ¢ 187 Outer Cape Cod and Nantucket Sound (1) This chapter describes the outer shore of Cape Cod rapidly, the strength of flood or ebb occurring about 2 and Nantucket Sound including Nantucket Island and the hours later off Nauset Beach Light than off Chatham southern and eastern shores of Martha’s Vineyard. Also Light. described are Nantucket Harbor, Edgartown Harbor and (11) the other numerous fishing and yachting centers along the North Atlantic right whales southern shore of Cape Cod bordering Nantucket Sound. (12) Federally designated critical habitat for the (2) endangered North Atlantic right whale lies within Cape COLREGS Demarcation Lines Cod Bay (See 50 CFR 226.101 and 226.203, chapter 2, (3) The lines established for this part of the coast are for habitat boundary). It is illegal to approach closer than described in 33 CFR 80.135 and 80.145, chapter 2. -

Management Plan for the Fin Whale (Balaenoptera Physalus), Atlantic Population in Canada

PROPOSED Species at Risk Act Management Plan Series Management Plan for the Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus), Atlantic Population in Canada Fin whale 2016 Recommended citation: DFO. 2016. Management Plan for the fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus), Atlantic population in Canada [proposed], Species at Risk Act Management Plan Series, DFO, Ottawa, iv +37 p. For copies of the management plan, or for additional information on species at risk, including COSEWIC Status Reports, residence descriptions, action plans, and other related recovery documents, please visit the Species at Risk Public Registry. Cover image: Véronique Lesage, DFO Available in French under the title “Plan de gestion du rorqual commun (Balaenoptera physalus), population de l’Atlantique au Canada” © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans Canada, 2016. All rights reserved. ISBN ISBN to be included by SARA Responsible Agency Catalogue no. Catalogue no. to be included by SARA Responsible Agency Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source. Management plan for the fin whale – Proposed 2016 PREFACE Under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996), the federal, provincial and territorial governments committed to a common approach to the efficient protection of species at risk throughout Canada that includes complementary legislation and programs. Under the Species at Risk Act (S.C. 2002, c. 29) (SARA), the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) is the competent minister for individuals of aquatic species which are not located in waters administered by the Parks Canada Agency. For the fin whales located in the Forillon National Park, the minister responsible for the Parks Canada Agency (Parks Canada) is the competent minister. -

Bird Observer VOLUME 34, NUMBER 1 FEBRUARY 2006 HOT BIRDS

Bird Observer VOLUME 34, NUMBER 1 FEBRUARY 2006 HOT BIRDS Phil Brown captured this image of a Selasphorous hummingbird (left) visiting Richard and Kathy Penna’s Boxford feeder. The bird remained for several weeks, and Phil Brown took this photo on November 20, 2005. On November 21, 2005, Linda Pivacek discovered a Scissor-tailed Flycatcher (right) at the Swampscott Beach Club, and Robb Kipp captured this breathtaking photo. This cooperative bird delighted many visitors over the following weeks. At Wellfleet Harbor, Blair Nikula picked out a Franklin’s Gull (left) in a large feeding flock on November 26, 2005. On December 11, Erik Nielsen took this stunning portrait of the cooperative rarity. On December 2, 2005, Gwilym Jones discovered a female Varied Thrush (right) on the Fenway in Boston. Andrew Joslin took this great photograph of this western wanderer. This bird was reported by many observers through January, 2006. CONTENTS BIRDING IN EAST BOSTON, WINTHROP, REVERE, AND SAUGUS Soheil Zendeh 5 MASSACHUSETTS IMPORTANT BIRD AREAS (IBAS) — THE SOUTH SHORE REGION Wayne R. Petersen and Brooke Stevens 26 LETTER TO THE EDITORS 32 ASUMMER AT MONOMOY Ryan Merrill 34 FIELD NOTE Latest Occurence of Arctic Tern for Massachusetts Richard R. Veit and Carolyn S. Mostello 38 ABOUT BOOKS Virtual Encyclopedia Ornithologica: The Birds of North America On-line Mark Lynch 40 BIRD SIGHTINGS September/October 2005 45 ABOUT THE COVER: Wild Turkey William E. Davis, Jr. 63 ABOUT THE COVER ARTIST: Barry Van Dusen 64 ATA GLANCE Wayne R. Petersen 465 IMMATURE NORTHERN SHRIKE BY DAVID LARSON BIRD OBSERVER Vol. 34, No.