Fishermen's Migrations in West Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transcending the Versification of Oraliture: Song-Text As Oral Performance Among the Ilaje

Venets: The Belogradchik Journal for Local History, Cultural Heritage and Folk Studies Volume 4, Number 3, 2013 Research TRANSCENDING THE VERSIFICATION OF ORALITURE: SONG-TEXT AS ORAL PERFORMANCE AMONG THE ILAJE Niyi AKINGBE Federal University Oye-Ekiti, NIGERIA Abstract. Oraliture is a terminology that is often employed in the de- scription of the various genres of oral literature such as proverbs, legends, short stories, traditional songs and rhymes, song-poems, historical narratives traditional symbols, images, oral performance, myths and other traditional sty- listic devices. All these devices constitute vibrant appurtenances of oral narra- tive performance in Africa. Oral narrative performance is invariably situated within the domain of social communication, which brings together the racon- teur/performer and the audience towards the realisation of communal enter- tainment. While the narrator/performer, plays the leading role in an oral per- formance, the audience’s involvement and participation is realised through song, verbal/choral responses, gestures and, or instrumental/musical accom- paniment. This oral practice usually take place at one time or the other in var- ious African communities during the festival, ritual/religious procession 323 which ranges from story- telling, recitation of poems, song text and dancing. This paper is essentially concerned with the illustration of the use of song- text, as oral performance among the Ilaje, a burgeoning coastal sub-ethnic group, of the Yoruba race in the South Western Nigeria. The paper will fur- ther examine how patriotism, history, death and anti-social behaviours are evaluated through the use of songs among the Ilaje. Keywords: oraliture, transcending the versification, song-text, oral per- formance, audience, communal entertainment, Ilaje ethnic group Introduction Oral art is embedded in the Ilaje’s tradition and cultural proclivity in the form of poetic and prose narratives, and these serve as important tools in the hands of the Ilaje poets, musicians and story-tellers. -

Stiwanismo En Un Contexto Africano 1

Stiwanismo en un contexto africano1 Stiwanism, feminism in an African context Molara Ogundipe-Leslie University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff. Recibido el 19 de marzo de 2002. Aceptado el 19 de abril de 2002. BIBLID [ l l 34-6396(2002)9: 1; 59-92] RESUMEN Molara Ogundipe plantea en este texto cuáles son las distintas situaciones de las mujeres africanas en el contexto actual, de un África en proceso de modernización pero en que a la vez las diferentes tradiciones continúan vivas, y cuáles han de ser los proyectos emancipatorios que las mujeres deberían llevar a cabo. En este sentido, Ogundipe hace un repaso histórico y considera que las mujeres han estado siempre presentes, en primer plano y de manera activa, en los procesos de liberación del continente africano, pero sus demandas han sido siempre relegadas a un papel secundario; y, asimismo, es evidente que no hay cambio social posible en positivo cuando no se cuenta con las mujeres. Así pues, la propuesta de Molara Ogundipe consiste en una Transformación Social que Incluya a las mujeres en África, el concepto Stiwanismo (Social Transformation Including Women in Africa). Palabras clave: Feminismos. África. Mujeres africanas. Stiwanismo. Imperialismo cultural. ABSTRACT In this text Molara Ogundipe raises the issue of the different situation of African women currently, in the context of Africa as a continent in the process of modemization, with different live traditions. She also focuses on the emancipatory projects that women engage in. In her review of history, Ogundipe considers that women are always present in a very active way, in the process of liberation of the African continent. -

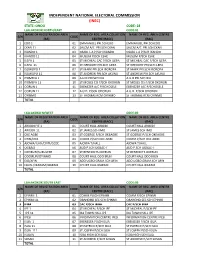

Ondo Code: 28 Lga:Akokok North/East Code:01 Name of Registration Area Name of Reg

INDEPENDENT NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION (INEC) STATE: ONDO CODE: 28 LGA:AKOKOK NORTH/EAST CODE:01 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 EDO 1 01 EMMANUEL PRI.SCHEDO EMMANUEL PRI.SCHEDO 2 EKAN 11 02 SALEM A/C PRI.SCH EKAN SALEM A/C PRI.SCH EKAN 3 IKANDO 1 03 OSABL L.A P/SCH IKANDO OSABL L.A P/SCH IKANDO 4 IKANDO 11 04 MUSLIM P/SCH ESHE MUSLIM P/SCH ESHE 5 ILEPA 1 05 ST MICHEAL CAC P/SCH ILEPA ST MICHEAL CAC P/SCH ILEPA 6 ILEPA 11 06 ST GREGORY PRI.SCH ILEPA ST GREGORY PRI.SCH ILEPA 7 ISOWOPO 1 07 ST MARK PRI.SCH IBOROPA ST MARK PRI.SCH IBOROPA 8 ISOWOPO 11 08 ST ANDREW PRI.SCH AKUNU ST ANDREW PRI.SCH AKUNU 9 IYOMEFA 1 09 A.U.D PRI.SCH IKU A.U.D PRI.SCH IKU 10 IYOMEFA 11 10 ST MOSES CIS P/SCH OKORUN ST MOSES CIS P/SCH OKORUN 11 OORUN 1 11 EBENEZER A/C P/SCHOSELE EBENEZER A/C P/SCHOSELE 12 OORUN 11 12 A.U.D. P/SCH ODORUN A.U.D. P/SCH ODORUN 13 OYINMO 13 ST THOMAS RCM OYINMO ST THOMAS RCM OYINMO TOTAL LGA:AKOKO N/WEST CODE:02 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ARIGIDI IYE 1 01 COURT HALL ARIGIDI COURT HALL ARIGIDI 2 ARIGIDI 11 02 ST JAMES SCH IMO ST JAMES SCH IMO 3 OKE AGBE 03 ST GOERGE P/SCH OKEAGBE ST GOERGE P/SCH OKEAGBE 4 OYIN/OGE 04 COMM.P/SCH OKE AGBE COMM.P/SCH OKE AGBE 5 AJOWA/ILASI/ERITI/GEDE 05 AJOWA T/HALL AJOWA T/HALL 6 OGBAGI 06 AUD P.SCH OGBAC-I AUD P.SCH OGBAC-I 7 OKEIRUN/SURULERE 07 ST BENEDICTS OKERUN ST BENEDICTS OKERUN 8 ODOIRUN/OYINMO 08 COURT HALL ODO IRUN COURT HALL ODO IRUN 9 ESE/AFIN 09 ADO UGBO GRAM.SCH AFIN ADO UGBO GRAM.SCH AFIN 10 EBUSU/IKARAM/IBARAM 10 COURT HALL IKARAM COURT HALL IKARAM TOTAL LGA:AKOKOK SOUTH EAST CODE:03 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. -

P E E L C H R Is T Ian It Y , Is L a M , an D O R Isa R E Lig Io N

PEEL | CHRISTIANITY, ISLAM, AND ORISA RELIGION Luminos is the open access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and rein- vigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org Christianity, Islam, and Orisa Religion THE ANTHROPOLOGY OF CHRISTIANITY Edited by Joel Robbins 1. Christian Moderns: Freedom and Fetish in the Mission Encounter, by Webb Keane 2. A Problem of Presence: Beyond Scripture in an African Church, by Matthew Engelke 3. Reason to Believe: Cultural Agency in Latin American Evangelicalism, by David Smilde 4. Chanting Down the New Jerusalem: Calypso, Christianity, and Capitalism in the Caribbean, by Francio Guadeloupe 5. In God’s Image: The Metaculture of Fijian Christianity, by Matt Tomlinson 6. Converting Words: Maya in the Age of the Cross, by William F. Hanks 7. City of God: Christian Citizenship in Postwar Guatemala, by Kevin O’Neill 8. Death in a Church of Life: Moral Passion during Botswana’s Time of AIDS, by Frederick Klaits 9. Eastern Christians in Anthropological Perspective, edited by Chris Hann and Hermann Goltz 10. Studying Global Pentecostalism: Theories and Methods, by Allan Anderson, Michael Bergunder, Andre Droogers, and Cornelis van der Laan 11. Holy Hustlers, Schism, and Prophecy: Apostolic Reformation in Botswana, by Richard Werbner 12. Moral Ambition: Mobilization and Social Outreach in Evangelical Megachurches, by Omri Elisha 13. Spirits of Protestantism: Medicine, Healing, and Liberal Christianity, by Pamela E. -

Medicinal Plants of Guinea-Bissau: Therapeutic Applications, Ethnic Diversity and Knowledge Transfer

Journal of Ethnopharmacology 183 (2016) 71–94 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Ethnopharmacology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jep Medicinal plants of Guinea-Bissau: Therapeutic applications, ethnic diversity and knowledge transfer Luís Catarino a, Philip J. Havik b,n, Maria M. Romeiras a,c,nn a University of Lisbon, Faculty of Sciences, Centre for Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Changes (Ce3C), Lisbon, Portugal b Universidade NOVA de Lisboa, Instituto de Higiene e Medicina Tropical, Global Health and Tropical Medicine, Rua da Junqueira no. 100, 1349-008 Lisbon, Portugal c University of Lisbon, Faculty of Sciences, Biosystems and Integrative Sciences Institute (BioISI), Lisbon, Portugal article info abstract Article history: Ethnopharmacological relevance: The rich flora of Guinea-Bissau, and the widespread use of medicinal Received 10 September 2015 plants for the treatment of various diseases, constitutes an important local healthcare resource with Received in revised form significant potential for research and development of phytomedicines. The goal of this study is to prepare 21 February 2016 a comprehensive documentation of Guinea-Bissau’s medicinal plants, including their distribution, local Accepted 22 February 2016 vernacular names and their therapeutic and other applications, based upon local notions of disease and Available online 23 February 2016 illness. Keywords: Materials and methods: Ethnobotanical data was collected by means of field research in Guinea-Bissau, Ethnobotany study of herbarium specimens, and a comprehensive review of published works. Relevant data were Indigenous medicine included from open interviews conducted with healers and from observations in the field during the last Phytotherapy two decades. Knowledge transfer Results: A total of 218 medicinal plants were documented, belonging to 63 families, of which 195 are West Africa Guinea-Bissau native. -

Toubab: an American Doctor in West Africa

BOOK REVIEWS Toubab: An American Doctor in toubab, experienced in Africa. He was Africa Medicine and Education West Africa assigned to the emergency department (WAME), a nonprofit program to help of the major hospital in The Gambia. His support medical care and general edu - By David Levine, DO. 281 pp, $25.00. ISBN: text relates numerous insightful experi - cation for West African children. The 978-0-9821064-1-9. Self-published; 2010. ences of friendships, cultural collisions, book notes that all profits from the sale sickness, frustrations, heartbreak, anger, of Toubab will be donated to WAME. The Gambia is a poor, small country in happiness, and much more. A couple Buying this book will help these kids West Africa in which day-to-day life is a examples follow: survive a difficult life. challenge. Healthcare services available My recommendation is to buy there are only a fraction of the services [Stunning to me were] the depth and Toubab and read it, and then try to pic - available in even the smallest towns in breadth of the chasm of ignorance of ture yourself living in such poor condi - the United States. I imagine that condi - the average Gambian about illness. A tions. You will leave Dr Levine’s story tions in most of Central Africa are sim - friend will report to me, “My auntie with a greater appreciation for what we ilar to those in The Gambia. In 2006, is in the hospital.” have in the United States, despite all the “Oh,” I say, “what is wrong with David Levine, DO, a family physician distractions that we’re experiencing in her?” from Washington State, volunteered for medicine today. -

![Addressing the Causes and Consequences of the Farmer-Herder Conflict in Ghana [ Margaret Adomako]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5843/addressing-the-causes-and-consequences-of-the-farmer-herder-conflict-in-ghana-margaret-adomako-175843.webp)

Addressing the Causes and Consequences of the Farmer-Herder Conflict in Ghana [ Margaret Adomako]

KOFI ANNAN INTERNATIONAL PEACEKEEPING TRAINING CENTRE POLICY BRIEF 6 | September 2019 Addressing the Causes and Consequences of the Farmer-Herder Conflict in Ghana [ Margaret Adomako] SUMMARY For several years, tensions have existed between local farmers and Fulani herdsmen in Ghana. However, various factors have recently, contributed to the tensions taking on a violent nature and becoming one of Ghana’s foremost security threats. Based on an extensive fieldwork conducted in 2016/2017, this policy brief discusses the causes of the Farmer-herder conflict and its consequences on the security, social and economic structures of the country. It looks at the shortfalls of Operation Cowleg, the major intervention that has been implemented by the state and concludes with a few policy relevant recommendations which includes a nationwide registration of herdsmen to support the government in the implementation of an effective taxation system. INTRODUCTION night grazing. The Asante Akyem North district of Ghana has Beginning from the late 1990s, the farmer-herder conflict has recorded various cases of this nature as a result of its lush become a recurring annual challenge for the Government vegetation. The district has a wet semi-equatorial climate with of Ghana. This conflict usually occurs between local farmers annual total rainfall between 125cm and 175cm making it a and herdsmen, mostly of the Fulani origin, over grazing lands favorite spot for crop farming2 and animal grazing especially and water sources in certain parts of Ghana. The conflict has in the dry season.3 Usually, during the dry season, herders been prevalent in Agogo, in the Ashanti region, and Afram from towns such as Donkorkrom and Ekyiamanfrom pass Plains in the Eastern region, although there have also been through Agogo on their way to Kumawu and Nyantakurom in recorded incidences in some parts of the Northern and Brong search of pasture during the dry season. -

Africans: the HISTORY of a CONTINENT, Second Edition

P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 This page intentionally left blank ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 africans, second edition Inavast and all-embracing study of Africa, from the origins of mankind to the AIDS epidemic, John Iliffe refocuses its history on the peopling of an environmentally hostilecontinent.Africanshavebeenpioneersstrugglingagainstdiseaseandnature, and their social, economic, and political institutions have been designed to ensure their survival. In the context of medical progress and other twentieth-century innovations, however, the same institutions have bred the most rapid population growth the world has ever seen. The history of the continent is thus a single story binding living Africans to their earliest human ancestors. John Iliffe was Professor of African History at the University of Cambridge and is a Fellow of St. John’s College. He is the author of several books on Africa, including Amodern history of Tanganyika and The African poor: A history,which was awarded the Herskovits Prize of the African Studies Association of the United States. Both books were published by Cambridge University Press. i P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 african studies The African Studies Series,founded in 1968 in collaboration with the African Studies Centre of the University of Cambridge, is a prestigious series of monographs and general studies on Africa covering history, anthropology, economics, sociology, and political science. -

MAC ADVICE Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing Activities

MAC ADVICE Illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing activities by Ghana’s industrial trawl sector and the European Union seafood market Brussels, 11 January 2021 1. Background The Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF) has published a report detailing ongoing and systemic illegal practices in Ghana’s bottom trawl industry1. The findings are indicative of a high risk that specific seafood species caught by, or in association with, illegal fishing practices continues to enter the EU market, and that EU consumers are inadvertently supporting illegal practices and severe overfishing in Ghana’s waters. This is having devastating impacts on local fishing communities, and the 2.7 million people in Ghana that rely on marine fisheries for their livelihoods2, as well as a negative impact on the image and reputation of those operators who are deploying good practices. The EU is Ghana’s main market for fisheries exports, accounting for around 85% of the country’s seafood export value in recent years3. In 2018, the EU imported 33,574 tonnes of fisheries products from Ghana, worth €157.3 million4. The vast majority of these imports involved processed and unprocessed tuna products, which are out of the scope of the present advice. 1 EJF (2020). Europe – a market for illegal seafood from West Africa: the case of Ghana’s industrial trawl sector. https://ejfoundation.org/reports/europe-a-market-for-illegal-seafood-from-west-africa-the-case-of-ghanas- industrial-trawl-sector. 2 Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) (2014) Cited in Fisheries Commission (2018). 2018 Annual Report. Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture Development. Unpublished. 3 Eurostat, reported under chapter 03 and sub-headings 1604 and 1605 of the World Customs Organization Harmonized System. -

Can Communities Close to Bui National Park Mediate the Impacts of Bui Dam Construction? an Exploration of the Views of Some Selected Households

Vol. 10(1), pp. 12-38, January 2018 DOI: 10.5897/IJBC2017.1132 Article Number: CF3BC2166929 International Journal of Biodiversity and ISSN 2141-243X Copyright © 2018 Conservation Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/IJBC Full Length Research Paper Can communities close to Bui National Park mediate the impacts of Bui Dam construction? An exploration of the views of some selected households Jones Lewis Arthur International Relations and Institutional Linkage Directorate, Sunyani Technical University, P. O. Box 206, Sunyani-Ghana. Received 24 July, 2017; Accepted 22 September, 2017 This paper explores the perceptions of families and households near Bui National Park, on the impact of Bui dam on their capital assets and how they navigate their livelihoods through the impacts of Bui Dam construction. The mixed methods approach was applied to sample views of respondents from thirteen communities of which eight have resettled as a result of the Bui Dam construction. In-depth interviews were conducted with 22 key informants including four families to assess the impacts of Bui Dam on community capital assets and how these communities near Bui Dam navigate their livelihoods through the effects of the dam construction, and whether the perceived effects of the Bui Dam differed for families in the different communities who were impacted by the dam construction. The results of the study showed that the government failed to actively integrate policies and programmes that could build on the capacity of communities to navigate their livelihoods through the effects of Bui Dam construction and associated resettlement process. Also, dam construction can have both positive and negative impacts on the livelihood opportunities of nearby communities. -

RECORDS CODIFICATION MANUAL Prepared by the Office Of

RECORDS CODIFICATION MANUAL Prepared by The Office of Communications and Records Department of State (Adopted January 1, 1950—Revised January 1, 1955) I I CLASSES OF RECORDS Glass 0 Miscellaneous. I Class 1 Administration of the United States Government. Class 2 Protection of Interests (Persons and Property). I Class 3 International Conferences, Congresses, Meetings and Organizations. United Nations. Organization of American States. Multilateral Treaties. I Class 4 International Trade and Commerce. Trade Relations, Treaties, Agreements. Customs Administration. Class 5 International Informational and Educational Relations. Cultural I Affairs and Programs. Class 6 International Political Relations. Other International Relations. I Class 7 Internal Political and National Defense Affairs. Class 8 Internal Economic, Industrial and Social Affairs. 1 Class 9 Other Internal Affairs. Communications, Transportation, Science. - 0 - I Note: - Classes 0 thru 2 - Miscellaneous; Administrative. Classes 3 thru 6 - International relations; relations of one country with another, or of a group of countries with I other countries. Classes 7 thru 9 - Internal affairs; domestic problems, conditions, etc., and only rarely concerns more than one I country or area. ' \ \T^^E^ CLASS 0 MISCELLANEOUS 000 GENERAL. Unclassifiable correspondence. Crsnk letters. Begging letters. Popular comment. Public opinion polls. Matters not pertaining to business of the Department. Requests for interviews with officials of the Department. (Classify subjectively when possible). Requests for names and/or addresses of Foreign Service Officers and personnel. Requests for copies of treaties and other publications. (This number should never be used for communications from important persons, organizations, etc.). 006 Precedent Index. 010 Matters transmitted through facilities of the Department, .1 Telegrams, letters, documents. -

Jeremy Mcmaster Rich

Jeremy McMaster Rich Associate Professor, Department of Social Sciences Marywood University 2300 Adams Avenue, Scranton, PA 18509 570-348-6211 extension 2617 [email protected] EDUCATION Indiana University, Bloomington, IN. Ph.D., History, June 2002 Thesis: “Eating Disorders: A Social History of Food Supply and Consumption in Colonial Libreville, 1840-1960.” Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Phyllis Martin Major Field: African history. Minor Fields: Modern West European history, African Studies Indiana University, Bloomington, IN. M.A., History, December 1994 University of Chicago, Chicago, IL. B.A. with Honors, History, June 1993 Dean’s List 1990-1991, 1992-1993 TEACHING Marywood University, Scranton, PA. Associate Professor, Dept. of Social Sciences, 2011- Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro, TN. Associate Professor, Dept. of History, 2007-2011 Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro, TN. Assistant Professor, Dept. of History, 2006-2007 University of Maine at Machias, Machias, ME. Assistant Professor, Dept. of History, 2005-2006 Cabrini College, Radnor, PA. Assistant Professor (term contract), Dept. of History, 2002-2004 Colby College, Waterville, ME. Visiting Instructor, Dept. of History, 2001-2002 CLASSES TAUGHT African History survey, African-American History survey (2 semesters), Atlantic Slave Trade, Christianity in Modern Africa (online and on-site), College Success, Contemporary Africa, France and the Middle East, Gender in Modern Africa, Global Environmental History in the Twentieth Century, Historical Methods (graduate course only), Historiography, Modern Middle East History, US History survey to 1877 and 1877-present (2 semesters), Women in Modern Africa (online and on-site courses), Twentieth Century Global History, World History survey to 1500 and 1500 to present (2 semesters, distance and on-site courses) BOOKS With Douglas Yates.