The Ugbo-Mahin Conflict and Its Implications for Social Development in Ilaje Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transcending the Versification of Oraliture: Song-Text As Oral Performance Among the Ilaje

Venets: The Belogradchik Journal for Local History, Cultural Heritage and Folk Studies Volume 4, Number 3, 2013 Research TRANSCENDING THE VERSIFICATION OF ORALITURE: SONG-TEXT AS ORAL PERFORMANCE AMONG THE ILAJE Niyi AKINGBE Federal University Oye-Ekiti, NIGERIA Abstract. Oraliture is a terminology that is often employed in the de- scription of the various genres of oral literature such as proverbs, legends, short stories, traditional songs and rhymes, song-poems, historical narratives traditional symbols, images, oral performance, myths and other traditional sty- listic devices. All these devices constitute vibrant appurtenances of oral narra- tive performance in Africa. Oral narrative performance is invariably situated within the domain of social communication, which brings together the racon- teur/performer and the audience towards the realisation of communal enter- tainment. While the narrator/performer, plays the leading role in an oral per- formance, the audience’s involvement and participation is realised through song, verbal/choral responses, gestures and, or instrumental/musical accom- paniment. This oral practice usually take place at one time or the other in var- ious African communities during the festival, ritual/religious procession 323 which ranges from story- telling, recitation of poems, song text and dancing. This paper is essentially concerned with the illustration of the use of song- text, as oral performance among the Ilaje, a burgeoning coastal sub-ethnic group, of the Yoruba race in the South Western Nigeria. The paper will fur- ther examine how patriotism, history, death and anti-social behaviours are evaluated through the use of songs among the Ilaje. Keywords: oraliture, transcending the versification, song-text, oral per- formance, audience, communal entertainment, Ilaje ethnic group Introduction Oral art is embedded in the Ilaje’s tradition and cultural proclivity in the form of poetic and prose narratives, and these serve as important tools in the hands of the Ilaje poets, musicians and story-tellers. -

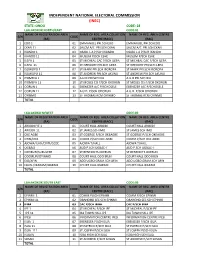

Ondo Code: 28 Lga:Akokok North/East Code:01 Name of Registration Area Name of Reg

INDEPENDENT NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION (INEC) STATE: ONDO CODE: 28 LGA:AKOKOK NORTH/EAST CODE:01 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 EDO 1 01 EMMANUEL PRI.SCHEDO EMMANUEL PRI.SCHEDO 2 EKAN 11 02 SALEM A/C PRI.SCH EKAN SALEM A/C PRI.SCH EKAN 3 IKANDO 1 03 OSABL L.A P/SCH IKANDO OSABL L.A P/SCH IKANDO 4 IKANDO 11 04 MUSLIM P/SCH ESHE MUSLIM P/SCH ESHE 5 ILEPA 1 05 ST MICHEAL CAC P/SCH ILEPA ST MICHEAL CAC P/SCH ILEPA 6 ILEPA 11 06 ST GREGORY PRI.SCH ILEPA ST GREGORY PRI.SCH ILEPA 7 ISOWOPO 1 07 ST MARK PRI.SCH IBOROPA ST MARK PRI.SCH IBOROPA 8 ISOWOPO 11 08 ST ANDREW PRI.SCH AKUNU ST ANDREW PRI.SCH AKUNU 9 IYOMEFA 1 09 A.U.D PRI.SCH IKU A.U.D PRI.SCH IKU 10 IYOMEFA 11 10 ST MOSES CIS P/SCH OKORUN ST MOSES CIS P/SCH OKORUN 11 OORUN 1 11 EBENEZER A/C P/SCHOSELE EBENEZER A/C P/SCHOSELE 12 OORUN 11 12 A.U.D. P/SCH ODORUN A.U.D. P/SCH ODORUN 13 OYINMO 13 ST THOMAS RCM OYINMO ST THOMAS RCM OYINMO TOTAL LGA:AKOKO N/WEST CODE:02 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ARIGIDI IYE 1 01 COURT HALL ARIGIDI COURT HALL ARIGIDI 2 ARIGIDI 11 02 ST JAMES SCH IMO ST JAMES SCH IMO 3 OKE AGBE 03 ST GOERGE P/SCH OKEAGBE ST GOERGE P/SCH OKEAGBE 4 OYIN/OGE 04 COMM.P/SCH OKE AGBE COMM.P/SCH OKE AGBE 5 AJOWA/ILASI/ERITI/GEDE 05 AJOWA T/HALL AJOWA T/HALL 6 OGBAGI 06 AUD P.SCH OGBAC-I AUD P.SCH OGBAC-I 7 OKEIRUN/SURULERE 07 ST BENEDICTS OKERUN ST BENEDICTS OKERUN 8 ODOIRUN/OYINMO 08 COURT HALL ODO IRUN COURT HALL ODO IRUN 9 ESE/AFIN 09 ADO UGBO GRAM.SCH AFIN ADO UGBO GRAM.SCH AFIN 10 EBUSU/IKARAM/IBARAM 10 COURT HALL IKARAM COURT HALL IKARAM TOTAL LGA:AKOKOK SOUTH EAST CODE:03 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. -

P E E L C H R Is T Ian It Y , Is L a M , an D O R Isa R E Lig Io N

PEEL | CHRISTIANITY, ISLAM, AND ORISA RELIGION Luminos is the open access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and rein- vigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org Christianity, Islam, and Orisa Religion THE ANTHROPOLOGY OF CHRISTIANITY Edited by Joel Robbins 1. Christian Moderns: Freedom and Fetish in the Mission Encounter, by Webb Keane 2. A Problem of Presence: Beyond Scripture in an African Church, by Matthew Engelke 3. Reason to Believe: Cultural Agency in Latin American Evangelicalism, by David Smilde 4. Chanting Down the New Jerusalem: Calypso, Christianity, and Capitalism in the Caribbean, by Francio Guadeloupe 5. In God’s Image: The Metaculture of Fijian Christianity, by Matt Tomlinson 6. Converting Words: Maya in the Age of the Cross, by William F. Hanks 7. City of God: Christian Citizenship in Postwar Guatemala, by Kevin O’Neill 8. Death in a Church of Life: Moral Passion during Botswana’s Time of AIDS, by Frederick Klaits 9. Eastern Christians in Anthropological Perspective, edited by Chris Hann and Hermann Goltz 10. Studying Global Pentecostalism: Theories and Methods, by Allan Anderson, Michael Bergunder, Andre Droogers, and Cornelis van der Laan 11. Holy Hustlers, Schism, and Prophecy: Apostolic Reformation in Botswana, by Richard Werbner 12. Moral Ambition: Mobilization and Social Outreach in Evangelical Megachurches, by Omri Elisha 13. Spirits of Protestantism: Medicine, Healing, and Liberal Christianity, by Pamela E. -

Petroleum Extraction, Agriculture and Local Communities in the Niger Delta

Petroleum Extraction, Agriculture and Local Communities in the Niger Delta. A Case of Ilaje Community. Adedayo Ladelokun Howard University Chapter I: Introduction Petroleum resource exploration and extraction-- ● A crucial economic activity ● Petroleum resources contributed substantially to economic development ● Conversely, petroleum exploration and extraction often induce negative impacts on other economic activities such as agriculture. ● Threatens environmental Safety. ● Ilaje Community,Ondo State,Nigeria, was chosen as a case study. Introduction Cont. ● Location and member states of the Niger Delta. Located in Coastal Southern Region of Nigeria. Map of the Niger Delta region Niger Delta Image of the Niger Delta Source: Ken Saro-Wiwa 20 years on Niger Delta ... Cnn.com Map of Ondo State Showing the 18 Local Government Areas Ilaje Local Government Introduction Cont. ● Population --- Estimated at 46 Million(UNDP) ● Geographical Landmark --- ND Covers area over 70,000 Sq Kilometers (ie 27,000 Miles) ● Occupation --- Farming, Fishing, Canoe Making, Trading, Net Making, and Mat Making. ● Ilaje Community --- Occupies Atlantic Coastline of Ondo State,Nigeria. ● Ilaje Local Government (Polluted Area) was one of the 18 Local Governments in Ondo State, Nigeria. ● Five Local Governments were randomly selected to served as control. Scope of the study This research work will cover Ilaje Community in Ondo State. Ondo State is located in the petroleum producing area of the Niger Delta Ilaje community was mainly into agricultural production Chapter II: Literature Review ● Agriculture in Economic Development of Nigeria: ○ Machinery for life sustenance ○ Supportive role raw material provision for industrial development ○ Todaro MP (2000) viewed role of AG as passive and supportive ○ Precondition for eco developed ○ Rapid structural transformation of the AG sector Literature Review Continues Jhingan M.L (1985) opined that: (a) AG provides food surplus for the rapidly expanding population. -

Prof.Adeolaadenikinju, Fnaee

PROFESSOR ADEOLA ADENIKINJU CURRICULUM VITAE By Prof.AdeolaAdenikinju, fnaee Professor of Economics, University of Ibadan & Director, Centre for Petroleum, Energy Economics & Law, University of Ibadan Fellow, Nigerian Association for Energy Economics (fnaee) Fellow, Energy Institute (FEI) 1 DETAILED CURRICULUM VITAE CURRICULUM VITAE: PROFESSOR ADEOLA FESTUS ADENIKINJU 1. Names in full: ADENIKINJU,Adeola Festus 2. Place and Date of Birth: Araromi-Obu, Ondo State; Oct. 6, 1966. 3. Nationality: Nigerian. 4. Marital Status: Married. 5. Number and Ages of Children: Four (4) Children: Toluwani, 21; Ayodeji (19); Daniel (17) and Victor (13). 6. Permanent Home Address:House 5, Rd 6, Alafia Estate, Akobo, Oju-Irin, Ibadan, Lagelu Local Government, Oyo State. 7. Present Postal Address: Professor AdeolaAdenikinju, FNAEE Department of Economics University of Ibadan Ibadan. Or Professor AdeolaAdenikinju, FNAEE Director, Centre for Petroleum, Energy Economics and Law (CPEEL), No. 7 ParryRoad, University of Ibadan, Ibadan. 8. Present Employment, and Status: University of Ibadan, Professor of Economics, and Director, Centre for Petroleum, Energy Economics and Law; 9. Educational Institutions Attended (with dates): (a) Primary: L.A. Primary School, Araromi-Obu 1971-1976 (b) Secondary: (i) Stella Maris College, Okitipupa 1978-1981 (ii) Ilusin Grammar School, Ilusin 1976-1978 (c) Tertiary: (i) University of Ibadan, Ibadan. (B.Sc) 1983-1987 (ii) University of Ibadan, Ibadan. (M.Sc) 1988-1990 (iii) University of Ibadan, Ibadan. (Ph.D) 1990-1994 2 10. Qualifications (with dates) (a) Academic: (i) Ph.D. (Econ) Ibadan, 1994 (ii) M.Sc. (Econ) Ibadan, 1990 (iii) B.Sc. (Econ) Second Class Honours, Upper Division, Ibadan, 1987 (iv) GCE A‟ Level 1983 (v) WASCE O‟ Level 1981 (b) Others (if any): NIL 11. -

The Case Study of Owo LGA, Ondo State, Nigeria

The International Journal Of Engineering And Science (IJES) ||Volume||2 ||Issue|| 9 ||Pages|| 19-31||2013|| ISSN(e): 2319 – 1813 ISSN(p): 2319 – 1805 Geo-Information for Urban Waste Disposal and Management: The Case Study of Owo LGA, Ondo State, Nigeria *1Dr. Michael Ajide Oyinloye and 2Modebola-Fadimine Funmilayo Tokunbo Department of Urban and Regional Planning, School of Environmental Technology, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria --------------------------------------------------------ABSTRACT-------------------------------------------------- Management of waste is a global environmental issue that requires special attention for the maintenance of quality environment. It has been observed that amount, size, nature and complexity of waste generated by man are profoundly influenced by the level of urbanization and intensity of socio-economical development in a given settlement. The problem associated with its management ranges from waste generation, collection, transportation, treatment and disposal. The study involves a kind of multi-criteria evaluation method by using geographical information technology as a practical instrument to determine the most suitable sites of landfill location in Owo Local Government Area of Ondo state. Landsat Enhanced Thematic Mapper plus (ETM+) 2002 and updated 2012 were used to map the most suitable site for waste disposal in Owo LGA. The result indicates that sites were found within the study area. The most suitable sites in the study area are located at 200metre buffer to surface water and 100metre to major and minor roads. The selected areas have 2500metres buffer zone distance from urban areas (built up areas). The study purposes acceptable landfill sites for solid waste disposal in the study area. The results achieved in this study will help policy and decision makers to take appropriate decision in considering sanitary landfill sites. -

Yoruba Studies Review, 2,1, Fall 2017: Special Edition

H-Africa Yoruba Studies Review, 2,1, Fall 2017: Special Edition Discussion published by Oloruntoyin Falola on Thursday, June 22, 2017 Views from the Shoreline: First Special Issue of Yoruba Studies Review, edited by Insa Nolte and Olukoya Ogen Views from the Shoreline: Community, trade and religion in coastal Yorubaland and the Western Niger Delta is the first Special Issue of Yoruba Studies Review (Vol. 2.1). Co-edited by Insa Nolte (University of Birmingham, UK) and Olukoya Ogen (Adeyemi College of Education Ondo, Nigeria), it arises from an ERC Starting Researcher Grant entitled ‘Knowing each other: Everyday religious encounters, social identities and tolerance in southwest Nigeria’. In addition to an introduction by the editors, Views from the Shoreline includes 19 articles by predominantly Nigerian researchers and a communiqué calling for greater political and academic engagement with the people and communities living on the coast. Views from the Shorelinetranscends dominant historical and anthropological approaches that center on the Nigerian hinterland’s capital cities and highlight the differences between ethnic and religious groups. Focusing on the high mobility and heterogeneity of communities on the Nigerian coastal stretch from the Yoruba town of Ikorodu (now a part of greater Lagos) along the Lagos lagoon and Ilaje coast up to Urhoboland and Benin, the Special Issue explores the coast as a borderland that has linked and provided refuge for different Nigerian groups as well as non-Nigerian settlers throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Views from the Shoreline address the methodological difficulties produced by the coast’s lack of centralization, its complex settlement histories, and its underrepresentation in government and mainstream mission archives through multi-methods approaches and in- depth fieldwork. -

A Sociological Post-Mortem of Issues in the Arogbo Ijaw-Ilaje Conflict: an Agenda for Peace

European Scientific Journal June 2015 edition vol.11, No.17 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 A SOCIOLOGICAL POST-MORTEM OF ISSUES IN THE AROGBO IJAW-ILAJE CONFLICT: AN AGENDA FOR PEACE Damilohun Damson, Ayoyo Department of Sociology, Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba, Nigeria Abstract Given the persistence, re-enactment and escalation of many ethnic conflicts in Africa, this study examined issues in the 1998/1999 Arogbo Ijaw-Ilaje conflict in Nigeria. This was done against the background that African leaders and mediating agencies often lack political will and commitment to resolve issues in ethnically-rooted conflicts. Using in-depth interviews and multi-stage sampling technique, 45 stakeholders from Arogbo-Ijaw and Ilaje were involved in the study. Findings revealed the Arogbo Ijaw-Ilaje conflict was centered on non-resolution of land and boundary dispute, struggle for resource control, fear of domination, marginalization, religious leadership crisis and quest for political autonomy arising from conflicts between the two groups in the past. Findings further revealed understanding ethnic conflicts goes beyond immediate factors to involve unresolved historical issues between groups concerned. The study concluded that non-resolution of issues in ethnic conflicts can undermine sustainable peace and provide ‘soft-spots’ for future re-enactment. The study recommended the need for peace builders, mediators, negotiators and parties to the conflict to direct peace efforts towards effective resolution of issues in the conflict as failure to do so would mean another evil day between the two ethnic groups may be ahead. Keywords: Arogbo Ijaw, conflict resolution, ethnic conflict, Ilaje, peace Introduction There is no gainsaying that a major problem in the world today is conflict. -

Adult Female Overweight and Obesity Prevalence in Seven

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 5 October 2020 doi:10.20944/preprints202010.0067.v1 Adult Female Overweight and Obesity Prevalence in Seven Sub-Saharan African Countries: A Baseline Sub-National Assessment of Indicator 14 Of the Global NCD Monitoring Framework Ifeoma D. Ozodiegwu, DrPH1, Laina D. Mercer, PhD2, Megan Quinn, DrPH3, Henry V. Doctor, PhD4, Hadii M. Mamudu, PhD5 1Institute for Global Health, Feinberg School of Medicine, University, Chicago, IL, United States of America 2Institute for Disease Modeling, Bellevue, Washington, United States of America (Current address: PATH, Seattle, Washington, United States of America) 3Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, East Tennessee State University, Johnson City, Tennessee, United States of America 4Department of Science, Information, and Dissemination, World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, Cairo, Egypt 5Department of Health Services Management and Policy, East Tennessee State University Johnson City, Tennessee, United States of America Corresponding author: Ifeoma D. Ozodiegwu Mailing address: Abbott Hall, 710 N. Lake Shore Drive, Suite 800 Email: [email protected] Phone: 4237731809 Keywords: Overweight, obesity, prevalence, women, Africa South of the Sahara Abstract Introduction Decreasing overweight and obesity prevalence requires precise data at sub-national levels to monitor progress and initiate interventions. This study aimed to estimate baseline age- standardized overweight prevalence at the lowest administrative units among women, 18 years and older, in seven African countries. The study aims are synonymous with indicator 14 of the global non-communicable disease monitoring framework. Methods We used the most recent Demographic and Health Survey and administrative boundaries data from the GADM. Three Bayesian hierarchical models were fitted and model selection tests implemented. -

Ondo State Conflictbulletin: Nigeria

THE FUND FOR PEACE Nigeria Conflict Bulletin: Ondo State Patterns and Trends, January 2012 - J u n e 2 0 1 5 While violence in Ondo has historically Democratic Party (PDP). The next page shows the relative distribution of been relatively low, in the first half of 2015 gubernatorial elections are scheduled for incidents from one LGA to the next from reported fatalities increased significantly as 2016. January 2012 to June 2015. The trendline on compared to previous years. This was the next page shows the number of mainly in connection to a few incidents of This Conflict Bulletin provides a brief incidents and fatalities over time. The bar criminality (bank robberies in Owo and snapshot of the trends and patterns of chart shows the relative trend of incidents Akoko North West LGAs) and piracy (Ilaje conflict risk factors at the State and LGA of insecurity by LGA per capita. LGA) that killed dozens. Other issues, levels, drawing on the data available on the reported in Ondo included political tensions P4P Digital Platform for Multi-Stakeholder The summaries draw on data collected by and cult violence. Engagement (www.p4p-nigerdelta.org). It ACLED, FFP’s UNLocK, the Council on represents a compilation of the data from Foreign Relations’ NST, WANEP Nigeria, CSS/ After the 2012 gubernatorial election, in the sources listed below, not necessarily the ETH Zurich, NEEWS2015, and Nigeria Watch which Olusegun Mimiko of the Labour Party opinions of FFP or any other organization integrated on the P4P platform. They also (LP) was re-elected, the losing parties raised that collaborated on the production of this draw on data and information from concerns about alleged election bulletin. -

The Vulnerability of Women to Climate Change in Coastal Regions of Nigeria: a Case of the Ilaje Community in Ondo State

Journal of Cleaner Production 246 (2020) 119015 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Cleaner Production journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jclepro The vulnerability of women to climate change in coastal regions of Nigeria: A case of the Ilaje community in Ondo State * Adenike A. Akinsemolu a, b, , Obafemi A.P. Olukoya a, c a The Green Institute, Ondo, Ondo State, Nigeria b Department of Microbiology, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria c Faculty of Architecture, Urban Planning and Civil Engineering, Brandenburg Technical University, Cottbus-Senftenberg, Germany article info abstract Article history: Values, patriarchal norms, and traditions related to gender and gendering are diverse among societies, Received 2 March 2019 communities, and precincts. As such, although climate change is expected to exacerbate vulnerabilities Received in revised form and deepen existing gender inequities and inequalities, the impacts will be unequally felt across 12 September 2019 geographical strata. This implies that the specificity of the vulnerability of women to climate change may Accepted 22 October 2019 also vary from community to community and society to societies. However, mainstream literature on the Available online 23 October 2019 vulnerability of women to climate changes in coastal zones trivializes the plurality and nuances of Handling editor: Yutao Wang different geographical contexts by universalizing context-specific vulnerability to climate change. Mindful of the limitations associated with the generalizing conception of women’s vulnerability, this Keywords: paper is therefore underpinned by the implicit assumption that a successful response to the vulnerability Women of women to climate change in coastal zone is forged in the nexus between contextual investigation of Vulnerability climate change parameters and a localized investigation of differentiation in gender roles, patriarchal Coastal region norms and other unknown factors in a particular setting. -

Foreign Influence on Igbomina, C

FOREIGN INFLUENCE ON IGBOMINA, C. 1750-1900 By ABOYEJI, ADENIYI JUSTUS 97/15CA020 (B.A. (2001), M.A. (2006) HISTORY, UNILORIN) BEING A Ph.D THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF ILORIN, ILORIN, NIGERIA i FOREIGN INFLUENCE ON IGBOMINA, C. 1750-1900 By ABOYEJI, ADENIYI JUSTUS 97/15CA020 (B.A. (2001), M.A. (2006) HISTORY, UNILORIN) BEING A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL, UNIVERSITY OF ILORIN, ILORIN, IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF ILORIN, ILORIN, NIGERIA © March, 2015 ii iii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to the custodian of all Wisdom, Knowledge, Understanding, Might, Counsel, Reverential Fear (Isaiah 11:2) and the Donor of the ‘pen of the ready-writer’ (Psalms 45:1), through our Lord and Saviour, JESUS CHRIST. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My indebtedness for accomplishing this study is undoubtedly, enormous. Contributions within the academic circles, family link and notable individuals/personages deserve due acknowledgement. This is because a man who beats up his doctor after he has been cured is incapable of being grateful. Nature‘s cruelty, to candour, is more bearable than man‘s ingratitude to man. Words are undoubtedly inadequate to quantify the roles of my supervisors, Dr. Kolawole David Aiyedun and Professor Samuel Ovuete Aghalino, to whom special accolades are exclusively reserved. In spite of their busy schedules as Head of Department, Senior Professor and in many other capacities, they never denied me the benefits of their supervisory acumen.